![]()

1 Space and Status

A whole history remains to be written of spaces—which would at the same time be the history of powers— . . . from the great strategies of geo-politics to the little tactics of the habitat.

—Michel Foucault, Power/Knowledge

Throughout history and across cultures, architectural and geographic spatial arrangements have reinforced status differences between women and men. The “little tactics of the habitat,” viewed through the lenses of gender and status, are the subjects of this inquiry. Women and men are spatially segregated in ways that reduce women’s access to knowledge and thereby reinforce women’s lower status relative to men’s. “Gendered spaces” separate women from knowledge used by men to produce and reproduce power and privilege.

Sociologists agree that, whether determined by the relationship to the means of production, as proposed by Marx, or by “social estimations of honor,” as proposed by Weber, status is unequally distributed among members of society and that men as a group are universally accorded higher status than women as a group (Blumberg 1984; Collins 1971; Huber 1990; Whyte 1978a). Status distinctions among groups of people constitute the stratification (social ranking) system of a society. Women’s status is thus a component of gender stratification, as is men’s status. “Women’s status” and “gender stratification” are used interchangeably throughout this book to designate women’s status in relation to men’s. “Gender” refers to the socially and culturally constructed distinctions that accompany biological differences associated with a person’s sex. While biological differences are constant over time and across cultures (i.e., there are only two sexes), the social implications of gender differences vary historically and socially.

Women and men typically have different status in regard to control of property, control of labor, and political participation. A variety of explanations exists for the persistence of gender stratification. Most theories are based on biological, economic, psychological, or social interpretations (Chafetz 1990). Our understanding of the tenacity of gender inequalities, however, can be improved by considering the architectural and geographic spatial contexts within which they occur. Spatial arrangements between the sexes are socially created, and when they provide access to valued knowledge for men while reducing access to that knowledge for women, the organization of space may perpetuate status differences. The “daily-life environment” of gendered spaces thus acts to transmit inequality (Dear and Wolch 1989, 6). To quote geographer Doreen Massey, “It is not just that the spatial is socially constructed; the social is spatially constructed too” (Massey 1984a, 6).

The history of higher education in America provides an example of the spatial contexts with which gender relations are entwined. Colleges were closed to women until the late nineteenth century because physicians believed that school attendance endangered women’s health and jeopardized their ability to bear children (Rosenberg 1982, 5; Rothman and Rothman 1987). In 1837 Mary Lyon defended her creation of the first college for women, Mt. Holyoke, by citing its role in “the preparation of the Daughters of the Land to be good mothers” (Watson 1977, 134). Mt. Holyoke was built in rural Massachusetts to protect its students from the vices of big cities (Horowitz 1984).

An initial status difference (the fact that few women were physicians and none sat on college admissions boards) translated into the exclusion of women from colleges. Spatial segregation, in turn, reduced women’s ability to enter the prestigious medical profession to challenge prevailing assumptions about the suitability of educating women. The location of knowledge in a place inaccessible to women reinforced the existing gender stratification system that relegated women to the private sphere and men to the public sphere.

A few pioneering women gained access to higher education, initially through segregated women’s colleges. They entered a different world from that of men’s colleges such as Harvard, Amherst, and the University of Virginia, which consisted of separate buildings clustered together around common ground. Male students moved from chapel to classroom to their rooms; dormitories had several entrances; rooms were grouped around stairwells instead of on a single corridor; and faculty lived in separate dwellings or off the campus entirely. In contrast, the first women’s colleges were single large buildings that housed and fed faculty and students in addition to providing space for classrooms, laboratories, chapel, and library under the same roof. Compared to the relative freedom of dispersed surroundings enjoyed by men, women were enclosed and secluded in a single structure that made constant supervision possible (Horowitz 1984, 4-22).

Women eventually entered coeducational institutions with men. Initially, though, they were relegated to segregated classrooms (Woody [1929] 1974, 2:285) or to coordinate (i.e., “sister”) colleges on separate campuses (Newcomer 1959, 40). Spatial barriers finally disappeared as coeducation became increasingly acceptable. As women attended the same schools and learned the same curricula as men, their public status began to improve—most notably with the right to vote granted by the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920.

Thus, both geographic distance and architectural design established boundaries between the knowledge available to women and that available to men. The existing stratification system depended on an ideology of women’s delicate health to deny them access to college. These resultant spatial arrangements, in turn, made it difficult for women to challenge the status quo. Once spatial barriers were breached, however, the stratification system began to change.

The Social Construction of Space

Geographic. Geographers have been the most vocal advocates of the integration of space into social theories. It is not sensible, they argue, to separate social and spatial processes: to “explain why something occurs is to explain why it occurs where it does” (Sack 1980, 70). Space is essential to social science; spatial relations exist only because social processes exist. The spatial and social aspects of a phenomenon are inseparable (Massey 1984a, 3; Dear and Wolch 1989).

Among sociologists and geographers who have addressed the spatial perspective are Durkheim (1915) on the social construction of space, Goffman (1959) on the presentation of front-stage versus backstage behavior, Reskin (1988) on the devaluation of women’s work, and Harvey (1973) on urban planning. Harvey identifies the city as a crucible in which the sociological and geographical imaginations become most compatible. The tendency to compartmentalize the shape of the city from the activities that constitute it should be avoided, since spaces and actions are different ways of thinking about the same thing (Harvey 1973, 26). The difficulty in achieving a synthesis is that social scientists do not yet possess a language adequate to the simultaneous occurrence of spatial form and social processes.

Part of the difficulty in establishing a common language is the tendency to think in causal terms: do spatial arrangements cause certain social outcomes or do social processes create spatial differentiation? Geographers are the first to point out the folly of “spatial fetishism,” or the idea that social structure is determined by spatial relations (Massey 1984b, 53; Urry 1985, 28). Yet it is also true that once spatial forms are created, they tend to become institutionalized and in some ways influence future social processes (Harvey 1973, 27). Although space is constructed by social behavior at a particular point in time, its legacy may persist (seemingly as an absolute) to shape the behavior of future generations.

Rather than thinking in terms of causality, Harvey proposes that space and social relations are so intricately linked that the two concepts should be considered complementary instead of mutually exclusive. Although it is necessary to break into the interactive system at some point to test hypotheses, whether one chooses spatial form as the input and social processes as the output or vice versa should be a matter of convenience (Harvey 1973, 46). Harvey suggests that instead of talking about either space or society causing certain outcomes, or the continuous interaction of space and society, efforts be made to “translate results generated in one language (say a social process language) into another language (the spatial form language). It is rather like translating from a geometric result to an algebraic result... both languages amount to different ways of saying the same thing” (Harvey 1973, 46-47). In other words, it is fruitless to try to isolate space from social processes in order to say that one “causes” the other. A more constructive approach is to acknowledge their interdependence, acknowledge how one tries to separate the two for analytic purposes, and then reintegrate the two. A geographer might emphasize a spatial-social language, while a sociologist might emphasize a socio-spatial language of explanation.

My hypothesis is that initial status differences between women and men create certain types of gendered spaces and that institutionalized spatial segregation then reinforces prevailing male advantages. While it would be simplistic to argue that spatial segregation causes gender stratification, it would be equally simplistic to ignore the possibility that spatial segregation reinforces gender stratification and thus that modifying spatial arrangements, by definition, alters social processes.

Feminist geographers have been pioneers on the frontier of theories about space and gender. In an article titled “City and Home: Urban Housing and the Sexual Division of Space,” McDowell (1983) argues that urban structure in capitalist societies reflects the construction of space into masculine centers of production and feminine suburbs of reproduction (see also Mackenzie and Rose 1983; Saegert 1980; and Zelinsky, Monk, and Hanson 1982). The “home as haven” constituting a separate sphere for women, however, becomes less appropriate as more women enter the labor force.

According to feminist geographers, a thorough analysis of gender and space would recognize that definitions of femininity and masculinity are constructed in particular places—most notably the home, workplace, and community—and the reciprocity of these spheres of influence should be acknowledged in analyzing status differences between the sexes. Expectations of how men and women should behave in the home are negotiated not only there but also at work, at school, and at social events (Bowlby, Foord, and McDowell 1986). The power of feminist geography is its ability to reveal the spatial dimension of gender distinctions that separate spheres of production from spheres of reproduction and assign greater value to the productive sphere (Bowlby, Foord, and Mackenzie 1982).

Architectural. Architectural space also plays a role in maintaining status distinctions by gender. The spatial structure of buildings embodies knowledge of social relations, or the taken-for-granted rules that govern relations of individuals to each other and to society (Hillier and Hanson 1984, 184). Thus, dwellings reflect ideals and realities about relationships between women and men within the family and in society. The space outside the home becomes the arena in which social relations (i.e., status) are produced, while the space inside the home becomes that in which social relations are reproduced. Gender-status distinctions therefore are played out within the home as well as outside of it (Hillier and Hanson 1984, 257-61).

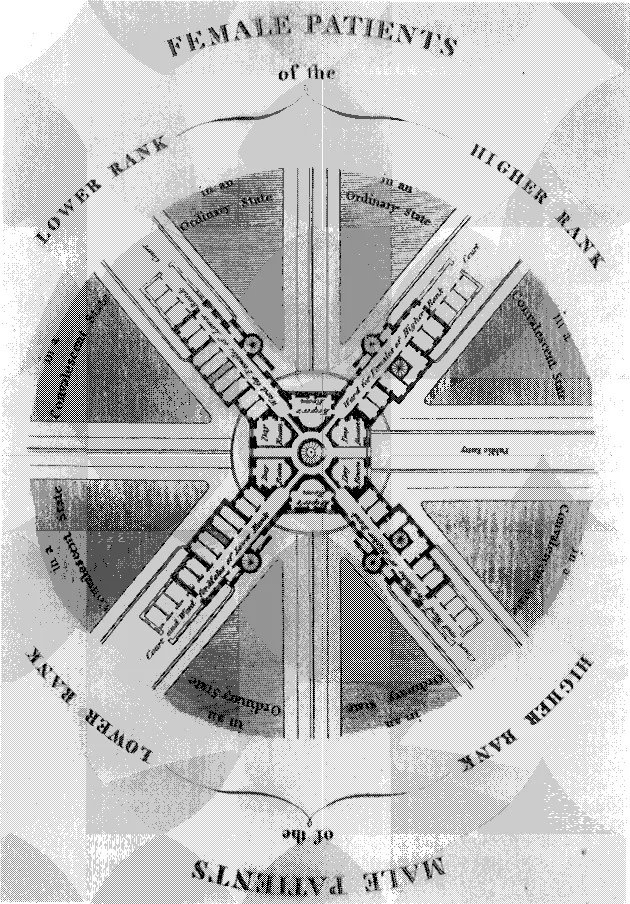

The use of architecture to reinforce prevailing patterns of privilege and to assert power is a concept dating from the eighteenth century with Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon (from the Greek, for all-seeing). A circular building of cell-like partitions, the Panopticon had at its center a tower allowing a supervisor to observe the occupants of each room. A window at the rear of each cell illuminated the occupant, and side walls prevented contact of occupants with each other. Such surveillance and separation inhibited the contagion of criminal behavior (in prisons), disease (in hospitals), or insanity (in asylums) (Foucault 1977, 200; Philo 1989).*

The Panopticon was “polyvalent in its applications,” an architectural system that existed independently of its specific uses. Foucault described it as a machine which could produce the relationships of power and subjection. “It is a type of location of bodies in space, of distribution of individuals in relation to one another, of hierarchical organization, of disposition of centers and channels of power . . . which can be implemented in hospitals, workshops, schools, prisons” (Foucault 1977, 202; see also Evans 1982, 198-206).

Prisons are the clearest examples of space being used to reinforce a hierarchy and to assert power, yet some schools of the eighteenth century were also built on panoptic principles. The École Militaire, designed by the architect Gabriel, was “an apparatus for observation”: rooms were small cells distributed along a corridor so that every ten students had an officer’s room on each side. Every room had a chest-level window in the corridor wall for surveillance, and students were confined to their rooms through the night. Teachers dined at raised tables to supervise meals, and latrines had halfdoors so the heads and legs of students could be seen. Side walls were sufficiently high, however, that students could not see each other (Foucault 1977, 173).

Bentham also was concerned with those “melancholy abodes appropriate to the reception of the insane.” He proposed that madhouses erected according to his guidelines could have beneficial effects on the mentally ill (Philo 1989, 265). Architect William Stark’s proposal for the Glasgow Asylum (in 1816) followed Bentham’s design, adding distinctions by gender, class, and level of illness. Men and women were separated, by social rank, into separate wings of the asylum depending on whether they were in an “ordinary” or “convalescent” state (Philo 1989, 268).

Fig. 1.1. William Stark’s preliminary panoptic plan for the Glasgow Asylum divides space by gender, social class, and degree of illness. Reproduced from “Third Report from the Committee on Madhouses in England,” Parliamentary Reports 6 (1816): 361, by permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

Panoptic principles could be applied to schools, prisons, and asylums; Bentham also recognized their application to the workplace. From the central tower a manager could supervise all his employees, whether they were nurses, doctors, foremen, teachers, or warders (Foucault 1977, 204). The manager could judge workers, alter their behavior if necessary, and deliver new instructions. One of the design’s special advantages was that “an inspector arriving unexpectedly at the center of the Panopticon will be able to judge at a glance, without anything being concealed from him, how the entire establishment is functioning” (Foucault 1977, 204). The manager had full view of the workers, while workers did not know if they were being observed. In this way the Panopticon reinforced the prevailing relationship between management and labor.

In the creation of new products, and in order to improve productivity, steps in the process of manufacturing were divided into components with a corresponding division of the labor force. The ability to compartmentalize labor and workers enabled managers to control the entire process of production, while workers understood only their own contribution rather than the entire process. Spatial control reinforced control of knowledge, which operated to deter labor from organizing against management.

Spatial Institutions

Over the course of the life cycle, everyone experiences one or more of the institutions of family, education, and the labor force. If we are to understand the systemic nature of gender stratification, it is to the interplay of these institutions that we must look (Brinton 1988). Equally important are the spaces within which institutional activities occur. Families must be analyzed in the context of dwellings, education in the context of schools, and labor in the context of workplaces. These “spatial institutions” form barriers to women’s acquisition of knowledge by assigning women and men to different gendered spaces. Masculine spaces (such as nineteenth-century American colleges) contain socially valued knowledge of theology, law, and medicine, while feminine spaces (such as the home) contain devalued knowledge of child care, cooking, and cleaning.

An institution, in sociological terms, refers to a patterned set of activities organized around the production of certain social outcomes. For example, the family is an institution because it is organized to reproduce future generations. Certain institutions are universal and evolve to fill requirements necessary to the maintenance of society. All societies must have the ability to biologically reproduce themselves, convey knowledge to members, produce goods and services, deal with the unknown, and preserve social order. Thus, some form of family, education, military, economy, religion, and system of legal justice exists in every society.

The activities that constitute institutions, of course, occur in specific places. Families live in homes, while education and religion are carried out in schools and churches. There is some overlap in institutions and the spaces they occupy. Educational and religious instruction, for example, may take place in the home, as does economic production in nonindustrial societies. Yet if one were to assign a primary spatial context to each major institution, the family would occupy the dwelling, education the school, economy the workplace, religion the church, and the legal system a courthouse. This book addresses the relationship between gender stratification and the spatial institutions of the family/dwelling, education/school, and labor force/workplace.

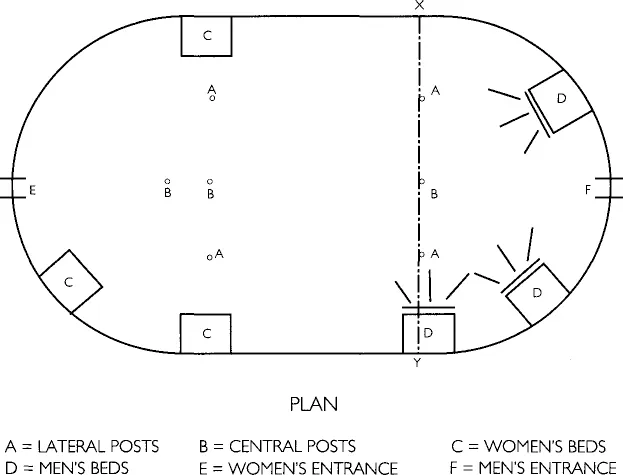

The Family and Segregated Dwellings. Nonindustrial societies often separate women and men within the dwelling (P. Oliver 1987). In a typical Purum house, for example, domestic space is divided into right/left, male/ female quarters, with higher value attributed to areas and objects associated with right/male and lower value associated with left/female (Sciama 1981, 91). Dwellings of the South American Jivaro Indians demonstrate a similar pattern, with the women’s entrance at the left end of the rectangular hut and a men’s entrance at the right end; women’s beds and men’s beds are arranged at their respective ends of jivaria (Stirling 1938). The traditional courtyard pattern of the Nigerian Hausa (used by both Muslim and non-Muslim families) also differentiates men’s from women’s spaces (Moughtin 1985, 56). Traditional Muslim households are divided into the anderun at the back for the women and the birun at the front for men (Khatib-Chahidi 1981).

Fig. 1.2. The men’s and women’s entrances are at opposite ends of the South American jivaria. Adapted from Stirling (1938).

A variety of cultural, religious, and ideological reasons have been used throughout history to justify gender segregation. Muslims, for example, believe that women should not come into contact with men who are potential marriage partners. The system of purdah was developed to keep women secluded in the home in a space safe from unregulated sexual contact, yet it also served to restrict women’s educational and economic opportunities. Muslim women therefore have lower status outside the home, compared with women in less sexually segregated societies (Mandelbaum 1988).

Nineteenth-century America and Great Britain had less overt forms of sex...