![]()

Chapter One: The History and Contemporary Context of the Windward Islands Banana Industry

The development literature is inundated with phrases such as “globalization” “restructuring,” “the new international division of labor in agriculture,” and other concepts intended to convey fundamental, contemporary changes in the post-World War II global economy, with especial reference to the period of perpetual crisis and upheaval since the 1970s. A recent tendency in the literature on contract farming is to link the growth of this institutional form to these broader processes (see Sanderson 1986b; Bonanno 1991; McMichael 1994c). For example, Watts (1994b: 248) asserts that “[c]ontract production in Africa as elsewhere is one manifestation of the late twentieth-century restructuring of agriculture that can only be fully comprehended as a global phenomenon.” Thus, post-Fordist trends toward corporate flexibility described in the literature on industrial restructuring—growth in the importance of niche markets, competition based increasingly on considerations of quality, product differentiation, and vertical disintegration and the concomitant expansion of subcontracting networks—are also viewed as propelling the rise of contract farming (Watts 1994a,b).

But a focus exclusively on the contemporary era hinders our understanding of the complex nature of contract farming in general and the Windward Islands banana industry in particular. Indeed, Watts (1994b: 256) is careful to point out that current processes associated with restructuring of the global economy do not explain the origins of contract farming. Thus, to place the industry in the proper perspective, our analysis must extend further back in time to trace its historical developments.

At the same time, the Windwards banana industry is subject to the winds of contemporary change, particularly in relation to forces associated with globalization. Especially relevant to the Windward Islands banana industry is the growth of regional economic organizations—in this case the European Community (EC) and its successor, the European Union (EU) and its Single European Market (SEM)—which emphasizes trade liberalization within its borders.1 The complex and changing patterns linking the British state and the Windward Islands to supranational institutions have had a fundamental influence on the history and viability of the Windwards banana industry.

Origins of the Windward Islands Banana Industry

The story of the Windward Islands banana industry and its relation to the U.K. market (the contemporary destination for Windwards bananas) begins neither in the Windward Islands nor in the United Kingdom. Rather, it starts elsewhere in the Caribbean—Jamaica—where a nascent banana export industry that was focused on supplying the United States market developed in the 1860s and 1870s. One of the enterprises involved in the early trade was the Boston Fruit Company, which grew rapidly and established plantations on the island. It subsequently merged with the banana-producing interests of Minor Keith, who had extensive plantations in Central America, to form the United Fruit Company in 1899 (later known as United Brands and today as Chiquita Brands International) (Sealy and Hart 1984). By the turn of the century, the banana industry, now dominated by United Fruit, was a significant component of the Jamaican economy, contributing 35 percent of exports (Beaver 1976: 23).

The British government, however, was growing increasingly concerned about U.S. corporate influence in the region. Thus in 1901 it provided a subsidy to the large British shipping firm of Elder Dempster for operation of a refrigerated service linking Jamaica and the United Kingdom to bring the fruit back from the colony.2 With the arrival of regular shipments of bananas from Jamaica, it appeared that American control and domination of the Jamaican industry had finally been broken. But such independence was short-lived. Elders and Fyffes, the British firm created to take over the trade from Elder Dempster, soon ran into financial difficulties, enabling United Fruit to gain increasing control over the firm and to acquire all its share capital by 1913 (Beaver 1976: 51–52). The ironic result was that a trade established to counter the United States’ influence in the region was now under the control of a U.S. corporation. United Fruit’s subsidiary (eventually referred to simply as Fyffes) was soon supplying the British market with bananas not only from Jamaica but also from Central and South America.

As Trouillot (1988) points out, the British government was alarmed by this state of affairs. The Imperial Economic Committee’s (1926) influential report on fruit production and trade in the British Empire highlighted this concern, lamenting the fact that “[a]n organization under American control monopolises the whole supply of bananas from Central America and Jamaica to the United Kingdom, thereby controlling the sales of 23 out of the 30 bananas consumed per head of the population in 1924” (13). Specifically the Imperial Committee complained that such a virtual monopoly was not in the best interest of the British consumer, the British government, or Jamaican farmers. Of particular concern was the fact that the purchase of such fruit required the expenditure of U.S. dollars, which contributed to Britain’s balance of payments problems.

The Imperial Committee also focused on the increasing complexity of the fruit trade, urging that banana growers in the British Empire be organized to facilitate production and marketing:

There is no organized method of expressing the views of banana growers in any particular Colony, and in the establishment of a shipping service it would be most important for the shipping line to be able to negotiate with some representative body which was able to guarantee regularity and adequacy of supplies. There is, moreover, the educational value of producers’ organisations in furthering the adoption of improved agricultural methods. [264–65]

It furthermore advised that such organizations “should in some way be under Government auspices to ensure that they were thoroughly representative in character and that their funds were applied to the purposes for which they were contributed” (265). At the same time, the Imperial Economic Committee also appealed for better quality standards in the grading, packing, and presentation of fruits. It concluded that financial assistance should be provided to help establish associations of banana producers in the British colonies (36).

Clearly, the major goal of the Imperial Committee was to lessen the grip of United Fruit on the British banana market. Its suggestion of forming banana growers’ associations to negotiate with shippers was related to its additional recommendation to encourage a British shipping firm to enter the trade and begin importing bananas not only from Jamaica but also from the Windward Islands, especially St. Lucia and Grenada, to help supply the U.K. market.

But of particular interest is that the conceptual seeds of the present-day Windwards banana industry based on contract farming were already firmly planted in the report over seventy years ago—long before the institution started to spread in developing countries. Key recommendations in the report—a statutory corporation that would regulate the industry, negotiate with shipping interests, and encourage improvements in fruit quality and packing; farmer education and training; and the provision of financial aid—all characterize the industry today. Clearly contract farming in the Windwards banana industry did not arise on the scene in the post–World War II era without significant roots in the past.

Although the Imperial Economic Committee was concerned about the supply of bananas to the British market and hoped that the Windwards would help alleviate the problem, the first sustained Windwards-wide banana export industry was directed at the Canadian market.3 Starting in 1933, the Canadian Banana Company, under the control of none other than United Fruit, began shipping bananas to Canada, the trade encouraged by reciprocal agreements between Canada and the Windward Islands (Spinelli 1973; Momsen 1992). As the Canadian Banana Company refused to negotiate with individual growers, statutory corporations were established on each island to promote development of the industry and negotiate with the shipping company, a pattern similar to that recommended by the Imperial Economic Committee (Mourillon 1978: 9). These banana growers’ associations each initially signed five-year contracts with the company, which agreed to buy all bananas considered suitable for export.

In the case of St. Vincent, the St. Vincent Banana Association was formed in 1934 and empowered as the exclusive exporter of bananas from the island. Both large-scale and peasant growers participated in the industry, with peasants making up the majority of growers. Compared with the industry today, banana production was not extensive, covering at most eleven hundred acres (Spinelli 1973: 184). Although farmers had a guaranteed market, the system cannot be considered as an example of true contract farming because no evidence is available to indicate that capital or the state intervened in the production process.

By the late 1930s, initial optimism concerning the trade’s prospects began to fade. Transportation problems within the Windwards, owing to the rudimentary road systems, contributed to the bruising of fruit, and as supplies increased, the company became increasingly selective in determining what was suitable for export (Mourillon 1978: 13). Another major problem was the variety chosen for export: the “Gros Michel” banana (Musa AAA Group) was highly susceptible to Panama disease, a fungal infestation. Just as it was devastating Gros Michel plantings in Jamaica and elsewhere in the Caribbean and Latin America, Panama disease took its severe toll on the Windwards industry. The declining industry finally collapsed in 1942, as disruption of shipping because of naval warfare severed the link to the Canadian market.

While the Windwards struggled to develop their own banana export industry, important changes occurred in the U.K. market. Specifically, the British government established the first in a long series of import policies that provided preferential treatment for banana producers within the empire—policies that would subsequently be essential for the growth and survival of the contemporary Windward Islands banana industry In 1932, it placed a tariff of £2.50 on each ton of bananas imported from non-empire sources, giving a considerable competitive edge to empire growers and enabling Jamaica increasingly to dominate the U.K. market. Before 1929, Jamaica supplied only 27 percent of that market, but by 1935, benefiting from the preferential tariff, it controlled 78 percent of that trade, increasing its dominance to 83 percent by 1938 (Sealy and Hart 1984: 87). But in 1940, with the onset of World War II, the government in the United Kingdom terminated all imports of bananas, curtailing the expansion of the Jamaican industry.

The banana export industries in both Jamaica and the Windwards did not revive until after World War II. With the conclusion of the war, the British Ministry of Food now became the exclusive importer of bananas, an arrangement that continued until 1953. The first bananas to arrive in the United Kingdom were from Jamaica in December 1945 (Beaver 1976: 83). But Jamaica was not able to supply all the needs of the now controlled British market, as its industry had declined during the war years. Thus, by 1948, Jamaican banana exports to the United Kingdom had fallen to less than one-third their prewar average (West India Committee Circular 1948: 187). This undersupplied British market provided the context for the emergence of the contemporary Windward Islands banana industry.

At the same time, the British made a decision that did not appear momentous at the time but would later have significant implications for the labor process and technological change in the Windwards. Specifically, in 1948 it designated the “Lacatan” variety of banana of the “Cavendish” group (Musa AAA Group) as also suitable for importation (West India Committee Circular 1948: 187). In contrast to the Gros Michel, which was the mainstay of the British market, the Lacatan was resistant to Panama disease. But the Lacatan had weaknesses of its own, one of which was susceptibility to another fungal infestation, leaf spot disease, or yellow Sigatoka leaf spot, but this was a less serious threat to bananas than Panama disease. A particularly crucial implication is related to the characteristics of the fruit of the Lacatan. Not only is the peel more tender than that of the Gros Michel, but the fingers of the hands of bananas do not lie as compactly on the stem (Hart 1954: 228). To those uninitiated into the intricacies of the banana trade, such differences would appear minor, hardly worth mentioning. In reality, both drawbacks make the fruit more susceptible to bruising during handling and transportation, a serious problem because the market became increasingly selective over time in relation to fruit quality.4 Coping with this susceptibility to bruising has led the Windwards into an endless series of technological innovations that have made the production process much more complex over time, a pattern that is the opposite of what one would expect from the concept of deskilling.

The year 1948 also marked the revival of the Windwards banana industry. Paddy Foley from Dublin and a Liverpool fruit merchant, Geoffrey Band, began negotiating to purchase all exportable bananas of the Lacatan variety from the Dominica Banana Association for fifteen years (see Mourillon 1978:15; Davies 1990: 184). They started shipping bananas in 1949, purchased land to grow the crop to supplement their supplies, and formed Antilles Products to handle the business. Initial shipments went to Dublin and the European continent but soon entered the undersupplied United Kingdom market as well (West India Committee Circular 1950: 110). Antilles subsequently contracted with St. Lucian growers in 1951.

The question remained whether the British market would provide the demand needed to spur the growth of the nascent Windwards industry. Indeed, many children had grown up in the United Kingdom during the war without ever seeing a banana. A minor incident in 1950 helped quell any doubts about potential demand in Britain: “[0]n December 6th a ship arrived at Liverpool from Sierra Leone with a cargo of bananas of which 78,000 were too ripe to be taken away. About 3,000 dock workers were told to eat all they could, and disposed of 37,000, an average of over 12 bananas each, before arrangements were made for disposing of the remainder” (West India Committee Circular 1951: 20). The English had not forgotten their love of bananas.

At the end of 1952, the British government announced its intention to cease direct purchases of all imported bananas and return the trade to the private sector and to remove all price and distribution controls on the fruit.5 It also announced an “open general license” that permitted the importation of bananas from sterling areas without the need to apply for special import licenses. In contrast, importation of so-called dollar bananas, bananas produced in Central and South America (except Brazil) that required the expenditure of U.S. dollars and thus were a drain on foreign currency reserves, required the issuance of specific licenses.6

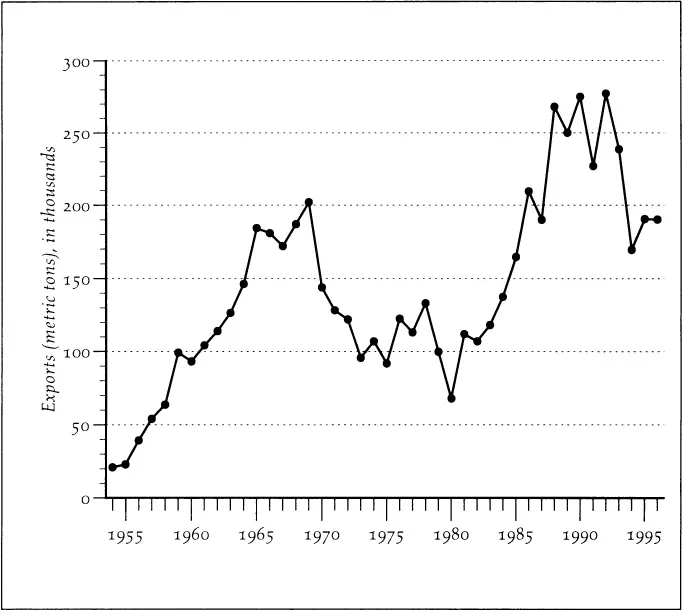

In the same year, another crucial change occurred in the Windwards (Trouillot 1988: 164). Antilles was having trouble arranging shipping to meet its commitments to purchase bananas and thus sold its interests to Geest Industries, Ltd., a rapidly growing British firm which had roots in Holland and which was involved in the vegetable and horticultural trade.7 Geest was receiving requests for bananas from its customers in the United Kingdom and was interested in obtaining its own supplies, as Fyffes monopolized the market at the time. The British government also encouraged Geest to enter the trade (Roger Hilborne, pers. comm., 23 January 1991). Antilles’ weaknesses provided a ripe opportunity, especially in light of the British government’s 1952 decision to return the trade to the private sector (Davies 1990). In 1954 Geest signed ten-year contracts with all four banana growers’ associations in the Windwards, guaranteeing to purchase all bananas of exportable quality and setting the minimum acceptable weight for a bunch at eighteen pounds. This guaranteed market, along with initially high prices for bananas, spurred rapid growth in the Windwards industry (see Figure 1.1), bringing a moderate rise in prosperity in the Windwards in the second half of the 1950s and leading to the popularity of the phrase “green gold.”

FIGURE 1.1. Windwards Banana Exports, 1954–1996

Sources: Grossman 1994; WINBAN annual reports; WIBDECO 1997.

The structure of the contemporary Windwards banana industry was now firmly in place. The banana industry on each island was regulated by a banana growers’ association that had the exclusive right to export the fruit. Each island’s association signed contracts with Geest, which, in turn, had exclusive rights to purchase all bananas from the Windwards. Moreover, the British market was now the clear destination for Windwards fruit.

The British Market and the Changing Regulatory Framework in the Postwar Era

Except for brief flickers of prosperity in the 1950s and 1980s, the Windward Islands banana industry in the postwar era has been in a precarious situation, limping from crisis to crisis. Recurrent drought and windstorms and occasional pest infestations from leaf spot, nematodes, and insects have plagued the industry and impeded growth.8 But the real potential threat has always been from Latin American growers, who have been able to produce better-quality bananas at significantly lower cost than have growers in the Windwards. They benefit from much more advantageous environmental conditions, one dimension of their competitive edge. Not only are they outside the hurricane belt, but they also have more favorable terrain—large stretches of flat, fertile land over which it is easier to transport bananas without bruising them, a substantial difference compared with the rugged terrain in the Windwards. Major economic adva...