- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

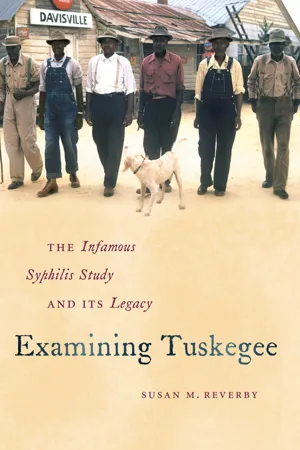

The forty-year Tuskegee Syphilis Study, which took place in and around Tuskegee, Alabama, from the 1930s through the 1970s, has become a profound metaphor for medical racism, government malfeasance, and physician arrogance. Susan M. Reverby’s Examining Tuskegee is a comprehensive analysis of the notorious study of untreated syphilis among African American men, who were told by U.S. Public Health Service doctors that they were being treated, not just watched, for their late-stage syphilis. With rigorous clarity, Reverby investigates the study and its aftermath from multiple perspectives and illuminates the reasons for its continued power and resonance in our collective memory.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Examining Tuskegee by Susan M. Reverby in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Public Health, Administration & Care. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Testimony

1

Historical Contingencies

Tuskegee Institute, the Public Health Service, & Syphilis

“Why us?” a family member of one of the men in the Study asked me at a meeting at the Shiloh Missionary Baptist Church in Notasulga, Alabama, just outside Tuskegee in 2007. The Study could perhaps have happened elsewhere. But, in many ways, the long-standing and complicated ties between Tuskegee Institute and the federal government over health care and disease in the black community provided the historical contingencies that made the Study possible, while only a disease as linked to sex and the black body and as widespread as syphilis could have brought them together for so long both in history and in imagination. The relationship between the PHS and Tuskegee Institute began de novo with the Study, but it had roots deep in the American ways that both had grown up and in the ties of disease to blackness.

The Contingency of Place

Tuskegee Institute was built in a small southern town in a county carved out of the huge southern lands of Native American peoples.1 When Alabama was admitted to the union as a frontier state in 1819, death by bear attack or in childbirth or through the cruelties of slavery in the fields, mills, and mines defined daily realities.2 In the 1840s, when the Indian wars ended with treaties that were broken over and over, Native American peoples were driven out and their land was given to whites, but not before they left their legacy behind in the bloodlines of both blacks and whites and in the names of towns like Tuskegee and Tallasee.3

By 1860, those identified as black Americans (both free and slave) outnumbered whites in Macon County by more than two to one. Small log or shotgun cabins outnumbered plantation homes in the red clay back ways, as barely 12 percent of Macon County’s white population identified themselves as slave owners.4 As in other parts of what became known as the Black Belt, cotton covered the fields made fertile by slave labor and trees filled the forests on the hills.5 Other enslaved African Americans worked in sawmills. Intense farming depleted much of the soil of the county, and small landowning white farmers had a hard time meeting even the minimal taxes to keep hold of their property.6 Except among the large plantation owners, a southern way of hardscrabble making-do dominated the working lives of most of Macon County’s black and white population.

Union soldiers during the Civil War did not make it into Tuskegee. But a battle a few miles out of the town at what would be the railhead at Chehaw was part of Sherman’s goal of making the resupply of Atlanta difficult. Purportedly, the college friendship between a northern officer and a planter, Edward Varner, kept the Union army from burning the town of Tuskegee down.7 As with much of the history of both the town and the institute, the vagaries of location, the link to the North, and the political skills and connections of the populace made things happen.

Reconstruction dashed many of the hopes of Macon County African Americans. Much too soon it became clear that, for many, slavery would be exchanged for a system resembling serfdom. The Alabama chief of the Freedmen’s Bureau advised the state’s newly freed men and women that they should “hope for nothing, but go to work and behave yourselves.”8 Work in this case meant contract labor that left most former slaves deep inside of a crop-lien system and outside of a cash economy.9 Migration in search of better land and more political power was on the minds of many Macon County African Americans: “A local Democratic paper . . . reported in 1876 that one party of forty blacks had just left the county, having been preceded by another group only days before, and that an emigration agent was working secretly in Tuskegee.” Between 1860 and 1870, the black population of the county dropped by over 5,000, but the fears on the part of white landowners that they would lose their entire black workforce proved baseless. Macon County’s black population remained at about 13,000 in the 1870s and 1880s.10

The African American men who did stay in the county made use of the new franchise by electing one representative to the state legislature as soon as possible. White conservatives vied with black and white Republicans for control over the county, often searching for ways to curry the favor of black voters. As elsewhere in the South, threats, terrorizing, and violence began to follow black voters who used their electoral power. By the end of the 1870s, white conservative control over the electoral process through both fraud and intimidation solidified.11

Tuskegee Institute itself was often subject to the vagaries of friendships and fortune, efforts at continued enforced racial compromise, and more hidden growing economic and political power.12 Many southern African Americans turned their hopes to education in the face of post-emancipation difficulties.13 Despite divisions over this, many white southerners also came to believe that at least some elementary education would be necessary to retain their black workforce and that teachers would have to be trained.

An ex-Confederate colonel and lawyer in Macon County and an ex-slave made a political deal that traded the promise of state aid for black education for voter support among black men to elect a white man to the Alabama legislature.14 It worked—the Alabama legislature made $2,000 available for “the Normal School for colored teachers in Tuskegee” in 1881. The funds, however, could not even cover the cost of the site of what Tuskegee Institute’s famed leader Booker T. Washington referred to as “‘the Farm’ . . . 100 acres of spent farmland on which stood ‘a cabin, formally used as a dining room, an old kitchen, a stable and an old hen-house’ where the ‘big house’ had burned down during the war.”15 Washington chose an apocryphal image when he recalled that the first animal given to the school by a local white patron was “an old blind horse.”16

On this plantation land, Tuskegee Institute began in Booker T. Washington’s imagination and in what he believed were the reflected hopes of both whites and blacks. Over the next three decades, Washington created what would become a vitally important educational institution in the rural South. As he told the story in his ghostwritten and carefully crafted 1901 autobiography, Up from Slavery, it was his ability to define and realize the needs of the black rural masses while translating them publicly to the local white population and to the noblesse oblige beliefs of northern and midwestern philanthropists that made Tuskegee Institute possible.17 By the time he died in 1915, there were, stunningly, “two thousand acres and one hundred buildings, with a faculty of nearly two hundred and an endowment close to $2 million.”18

On that original land rose buildings built brick by brick by the students and an education that emphasized respectability, cleanliness, and manual labor.19 Washington’s well-known ironfisted control focused on the most minute details of the institute and its citizens’ daily lives, down to his supervision of tooth brushing and his weekly exhortations at chapel about behaviors. Policing of his students’ black bodies was critical to his effort to obtain what one critic calls the “recuperation of dirt” and the maintenance of “self control,” which led to “politicizing the domestic to gain social control.”20

Tuskegee Institute maintained a complicated relationship with the nearby rural “folk” as well, reaching out to teach, uplift, and serve through what was called the Movable School program, and yet condemning what was seen as the “dirt” and sexuality of black rural life.21 Containment of the “corporeal” black body and the “contagion of ‘sexuality’ as disease,” both inside and outside Tuskegee Institute, was absolutely central to Washington’s efforts.22 He tried to create what came to be called “a New Negro,” in a break from the perceived “stereotypes” of licentiousness and “minstrelsy.”23

On the surface, Washington cooperated with the tightening hold of Jim Crow segregation, which denied black Americans political and voting rights, underfunded a separate educational system, sustained economic peonage, and kept power through frequent eruptions of state-sanctioned violence.24 The need to carefully gauge the appropriate balance of the needs of blacks and whites and meet the financing of the institute continually haunted Washington’s efforts. Teachers and students at Tuskegee acceded to “elaborate rituals of segregation” when whites came to visit. They kept the institute away from those blacks who directly challenged the system. They presented white philanthropists with an institution for African American education they could fund without compromising the sensibilities of the majority of southern whites.25 In doing so, Washington was able to build up a black educational institution with black faculty and an increasing local black middle class of teachers, professionals, and small landowners.26

Even as Tuskegee Institute made education and economic progress possible for some, however, it never overcame the real dangers that shaped the violence of daily life. Despite expectations and promises, African Americans in and around the town of Tuskegee had to be very careful not to cross carefully delineated lines of white beliefs about racial appropriateness. A “hard look,” as one Tuskegee resident noted, from a white man, could spell danger.27

And, in the end, even Washington could not hide from the myths of black male sexuality and the cultural meaning of the black body that was embedded in parts of American culture. His serious illnesses (kidney disease, arteriosclerosis, and high blood pressure) led to his collapse and hospitalization on November 10, 1915, in New York City. The St. Luke’s Hospital physician he saw told reporters: “There is a noticeable hardening of the arteries and he is extremely nervous. Racial characteristics are, I think, in part responsible for Dr. Washington’s breakdown.” Such terminology infuriated Washington’s supporters. As one of his doctors wrote: “[Racial characteristics] . . . means a ‘syphilitic history’ when referring to Colored people.” Washington was never tested for syphilis, and he died of kidney failure brought on by high blood pressure. It was not until ninety years later that a medical review finally confirmed that he was not syphilitic.28

Washington’s power gave him the means to institutionalize his focus on the body and discipline in Tuskegee and beyond. In 1902, Washington brought surgeon John A. Kenney Sr. to Tuskegee to run a small hospital and the nurses’ training program, which had begun a decade earlier. Health facilities at Tuskegee remained very sparse until 1912, when Boston philanthropist Elizabeth Mason gave the funds to build the John A. Andrew Memorial Hospital, named after her grandfather and Massachusetts’s governor during the Civil War.29 It provided both acute and preventive care, serving as Macon County’s health department until 1928 and even after 1928 providing physical space. Although it was a private hospital for the institute’s students, faculty, and staff, it was increasingly called upon to be a community hospital for needy black people throughout the Black Belt.

Under Kenney’s leadership and with his connections to the National Medical Association (formed in 1895 because racism kept black physicians from membership in the American Medical Association), an annual clinic was organized that brought patients and physicians together. At the first clinic in 1912, the visiting doctors treated 440 patients, performed 36 operations, and announced happily that everyone “recovered.” By 1918, the John A. Andrew Clinic became the John A. Andrew Clinical Society, dedicated to “the advancement of physicians and surgeons in the science and art of medicine and surgery and the study and treatment of morbid conditions affecting thousands of needy sufferers in this section of the South.”30 The annual meetings provided one of the few post-medical school training opportunities for black physicians, surgeons, and dentists—under big-name white doctors, who were invited to lecture and demonstrate the latest techniques. It gave patients from black communities throughout Alabama, barred from care elsewhere, a chance to receive treatment. However, unwittingly, as for poor people, white and of color, from throughout the country, they became “teaching material” as well for those learning the newest methods.31

Washington understood that freedom required health and that self-improvement had to be linked to the provision of services.32 He was not alone. As understandings that germs caused disease layered upon older sanitarian notions, the Atlanta Constitution’s astute phrase “germs ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Examining Tuskegee

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- PART I Testimony

- PART II Testifying

- PART III Traveling

- Epilogue

- APPENDIX A Chronology

- APPENDIX B Key Participant’s Names

- APPENDIX C Men’s Names

- APPENDIX D Tables and Charts

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index