- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The Journal of the Civil War Era

Volume 4, Number 3, September 2014

TABLE OF CONTENTS Editor's Note, William Blair

Articles

Felicity Turner

Rights and the Ambiguities of Law: Infanticide in the Nineteenth-Century U.S. South Paul Quigley

Civil War Conscription and the International Boundaries of Citizenship Jay Sexton

William H. Seward in the World Review Essay

Patick J. Kelly

the European Revolutions of 1848 and the Transnational turn in Civil War History Book Reviews

Books Received

Notes on Contributors

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

William H. Seward in the World

When William Henry Seward returned to Auburn, New York, in 1871 after nearly two years of travel, he intended to write his political memoirs. “It would seem to me that I might be able to tell a story that would contain some instruction for my fellow men,” Seward informed George Bancroft, who had encouraged him to write his autobiography.1 But then Seward did something unexpected. He shelved his memoirs and instead coauthored a book about his recent world travels with Olive Risley Seward, his travel companion and adopted daughter. The project consumed them in the final year of William Henry’s life—indeed, he was editing the manuscript the day he died, in October 1872. The posthumous and commercially successful William H. Seward’s Travels around the World (1873) informed its many readers of the era’s accelerating processes of global integration.2 Both an account of Seward’s world tour and an affirmation of the nationalist principles and practices he promoted throughout his political career, Travels is a key text in the transnational history of the Civil War era.

The significance Seward—the most notable U.S. public figure to that point to complete a world tour—accorded to his travels stands in contrast to scholars’ neglect, if not dismissal, of them. “Its historical interest is slight,” Glyndon Van Deusen declared of Travels. 3 This essay disagrees. Seward’s travels provide one of the best opportunities to examine how a leading U.S. nationalist of the Civil War era understood and interacted with an early phase of the phenomenon historians now call “modern globalization.”4 Seward’s travel writings and speeches constituted an early intervention in what became a protracted discussion concerning how the reunified United States should relate to a world entering an era of rapid integration conditioned by imperial power, particularly that of Great Britain. Seward’s embrace of U.S. nationalism and expansion, his celebration of Anglo-American rapprochement and unity, his championing of technological innovation and infrastructure development, his “civilizationist” vocabulary—all these helped establish the terms in which his successors conceptualized and pursued America’s world role. Most important of all was how Seward fused an understanding of global “civilization” with the nationalism that had defined his era and political career.

Seward was at once one of his era’s leading nationalists and foremost cosmopolites. This accomplished secretary of state possessed a profound knowledge of events around the globe; yet his understanding of the world was conditioned—indeed, often distorted—by the nationalist prism through which he looked. This entwinement of nationalism and cosmopolitanism is evident in his “civilization,” a keyword of the era that was foundational to his worldview. Often contrasted with “barbarism” or “savagery,” it denoted a developmental process in which the “uncivilized” worked toward the pinnacle of “civilization.” This versatile term has attracted scholarly attention, most recently from Frank Ninkovich, whose multifaceted definition is worth quoting: “Civilization was, inter alia, a universalizing historical process, a geographic designation, an anthropological category, a value-laden binary distinction usually paired in opposition to ‘barbarism,’ a term connoting evolutionary differences in social structure and the life of the mind, a word that could carry class and regional meanings. . . . Depending on the context, its purport could be hierarchical or egalitarian, pacific or belligerent, Euro-American or global, faux-cosmopolitan or genuinely ecumenical.”5 Seward appears not to have defined “civilization”; to him its meaning self-evidently flowed from the practices and values he associated with the United States. “Civilized” peoples exchanged goods and technologies, rather than retreating into isolation; they embraced Western ideas and religious tolerance, eschewing anachronistic and illiberal belief systems; they celebrated economic modernization; they moderately pursued incremental reform.

Seward’s conception of “civilization” embodied the paradox examined in this essay: it was at once global in scope and the product of his U.S. nationalism. This essay examines Seward’s travel writings, the speeches he gave abroad, and, crucially, the accounts of his foreign interactions documented by those who observed him during his travels, most notably those found in the records of British and U.S. consuls.6 These sources reveal the global reach of the United States and the ambitions held for it by one of its leading statesmen circa 1870. But on another level, following Seward around the globe highlights the limits of the U.S. presence in the world by bringing into focus the many ways America’s overseas position was dependent on the transnational structures of the era’s expanding empires, particularly those of the British Empire.7 British power did more than simply shape Seward’s itinerary; it also helped shape his view that imperial power could play a constructive and benign role in fostering the spread of “civilization.” It is perhaps surprising that this reputed Anglophobe came to embrace the British Empire while abroad. Yet, Seward’s celebration of Anglo-American unity—like his optimistic depiction of the progress of “civilization” more generally—derived from the confident nationalism he carried around the globe.

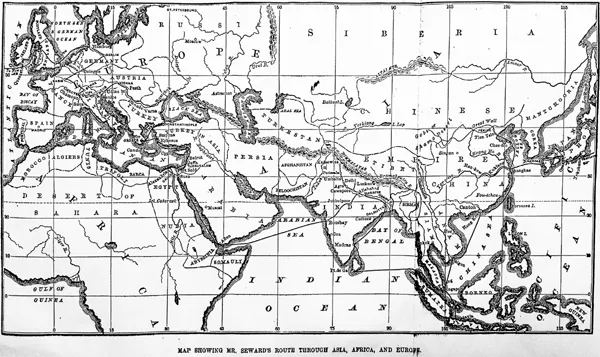

Seward began this journey in August 1870 by again traveling west across the transcontinental railroad. On reaching San Francisco, he boarded a Pacific Mail steamer for Japan, where he remained for two months. Next was China, where he toured extensively, arriving in Tientsin just months after the anti-missionary uprising there, and even making it to the notoriously inaccessible city of Peking. He then moved south to Cochin China and Java, before steaming through the Strait of Malacca en route to British India. In South Asia, the Seward party ventured far inland along newly constructed British railways (and, on one occasion, using an older method of transport, the back of an elephant). Seward then steamed to the Near East, making use of the newly opened Suez Canal. In Egypt, he journeyed up the Nile (celebrating his seventieth birthday amid ancient ruins), before visiting the Holy Land, Greece, and the heart of the Ottoman Empire in Constantinople. In July 1871, he reached the more familiar confines of Europe, where he conducted a whirlwind tour of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Italy, Switzerland, France, Germany, and Britain. Finally, in October 1871, he boarded a steamer in Liverpool that returned him to New York.

This remarkable journey was made possible by revolutionary advances in global transport and communications. Seward was one of the first public figures to make use in a single journey of three of the great infrastructural achievements of the nineteenth-century: the U.S. transcontinental railroad (opened in 1869), the first transpacific steamship line (inaugurated in 1867), and the Suez Canal (opened in 1869). He also encountered new railroads in Mexico, Japan, and India. He sent and received cables on newly laid telegraph lines and used them to keep abreast of developments in the Franco-Prussian War. He carried with him a map of telegraph lines under construction, given to him by American financier Cyrus Field—indeed, the first question Seward asked when he arrived in a new port was whether it was yet connected to the telegraph.8

Figure 1

Seward’s route through Asia, Africa, and Europe. William H. Seward and Olive Risley Seward, William H. Seward’s Travels around the World (New York: D. Appleton, 1873).

Seward’s route through Asia, Africa, and Europe. William H. Seward and Olive Risley Seward, William H. Seward’s Travels around the World (New York: D. Appleton, 1873).

If Seward at times strayed from major ports and the cities connected to them by rail—most notable were his treks across Mexico and to Peking—his journeys generally followed the trunk lines of nineteenth-century commerce. His route was similar to those discussed in the era’s travel narratives, particularly Charles Coffin’s aptly titled Our New Way Round the World (1869).9 “You can buy your ‘through ticket’ in New York,” Seward is reported to have said after his travels, “and go from steamer to railway, and railway to steamer, stopping at ports occasionally, where you will find hotels and tourists, merchants and missionaries, people talking English, and dinners and tea parties, like what you see at home.”10 The infrastructure that dictated Seward’s itinerary meant that the world he visited was one profoundly shaped by nineteenth-century empires: the French and Dutch, the Ottoman, and, above all others, the British.

The journey would have been impossible for a man of Seward’s condition before the opening of new railroads and steamship lines. He was disfigured from an 1865 assassination attempt, had limited use of his arms, and required a “wheeled chair” when moving even short distances. He resorted to nocturnalism in climes in which his signature Panama hat did not provide enough relief from the sun. He was fortunate to have the strength to overcome an illness in India. Observers uniformly expressed their amazement that a man of Seward’s age and condition could endure the journey. They also were of one voice in commenting on his razor-sharp mind, as well as the prickliness and incivility that presumably derived from fatigue and declining health.11

Seward was accompanied by a small and often changing group that included Olive and her sister Hattie (and, for the first part of the journey, Hanson, their biological father and long-time associate of Seward’s), his African American servant William Freeman, and, as far as Shanghai, George F. Seward, his nephew and future minister to China. On his retirement, Seward had feared that “rest was rust” and viewed travel as a way of prolonging his life.12 It is likely that another motive for the journey was to spend time with Olive away from intrusive newspaper reporters, who had discovered that Seward, lonely after the recent deaths of his wife, Frances, and daughter Fanny, was infatuated with his associate’s twenty-five-year-old daughter.13 If Seward’s intention was to sidestep controversy, the plan was unsuccessful. Concern for Olive’s reputation led Seward to adopt her at the U.S. consulate in Shanghai to put an end to rumors by establishing a pretext for their intimacy. Clearly, there were personal reasons for Seward to embark on his travels. Yet the evidence suggests that Seward undertook the journey for more than reasons of he...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- The Journal of the Civil War Era

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Editor’s Note

- Rights and the Ambiguities of Law

- Civil War Conscription and the International Boundaries of Citizenship

- William H. Seward in the World

- Review Essay

- Book Reviews

- Books Received

- Contributors

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Journal of the Civil War Era by William A. Blair in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.