![]()

PART I

A Young Man’s Path into the Atlantic World

If you cannot accept me as I am, then I cannot help it and can do no differently. The Lord himself would have to make me different, should He so want it.

—Jean-François Reynier to Moravian bishop David Nitschmann, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, 1743

The stubborn man who made this statement did so in the middle of a lifelong odyssey. As a disaffected youth, he had left his home in the Swiss Alps to find spiritual truth abroad, and his journey took him to many important places in the Atlantic World. His spiritual journey became a voyage of self-discovery, during which he developed many practical skills that allowed him to continue his search. But he also learned that he could not live and work well with those around him. He strove to control himself and his obsessions, but he failed, and personal rejection, alienation, and madness followed. He went to the marriage altar as a talented, experienced Atlantic traveler who remained a troubled soul—an enigmatic person who had not yet found the truth. But he was hopeful that he soon would.

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Alpine Origins

I had not been persecuted by the authorities, as is usually the case when one withdraws from a godless life and society, but I did seek to rid myself of daily encounters with my physical relatives. . . . I saw how filled with sin I was and how this sin separated me from my God. I then reflected on my situation and promised God that I would better myself.1

—Jean-François Reynier, explaining why he left home for Pennsylvania in 1728

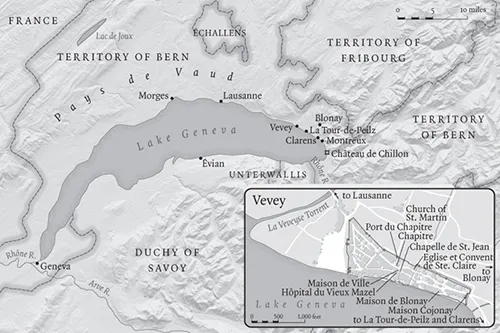

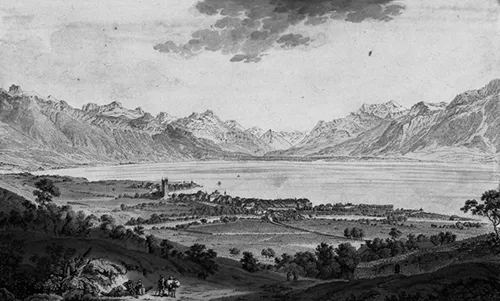

In 1712, Jean-François Reynier saw the light of his first day in the small town of Vevey on the northeastern shore of Lake Geneva in the Pays du Vaud (Canton Vaud). Vevey lay in a beautiful Alpine setting. A wall of mountains protected the town from cold north winds, and before it lay the thirteen-mile-wide lake. Beyond the lake, a chain of magnificent, snow-covered peaks dominated the southern horizon. To the east, glaciers receding at the end of the Ice Age had carved a broad valley through which the Rhône River meandered until it emptied into the lake. To the west lay Lausanne and a number of small towns and castles leading toward the end of the lake and the city of Geneva, where Jean-Jacques Rousseau was born in the same year.

Until the time of Reynier’s childhood, this stunning natural panorama had frightened many into staying away. In the Medieval period, most people imagined the Alps as the abode of witches, devils, giants, and wild beasts. Even when Reynier was a child, a scientist drew up a list of all known dragons in eastern Switzerland. In 1719, a party of travelers on a spiritual journey from the Rhineland stayed in a tavern high in the mountains the night before reaching Vevey. While there, they heard a story about a number of people who had been murdered in the isolated settlement a few years earlier. One of the travelers recorded that he spent a sleepless night, haunted by dark figures and specters, until the Lord sent an angel to watch over him. The next day, the seven-year-old Jean-François Reynier was among those the travelers met in Vevey.2

Map 2. Lake Geneva in the early eighteenth century

During Reynier’s lifetime, however, the Romanticists began to change perceptions of this Alpine world. In 1732, a mathematician, botanist, and entrepreneur poet named Albrecht von Haller published a poem called “Die Alpen” (The Alps) that celebrated the natural splendor of the region and idealized peasant life there. In 1728, Rousseau met Madame de Warens, recently from Vevey, and fell in love with her. They lived together throughout the 1730s, and through her influence he became infatuated with the wild scenery of the Alps. Rousseau used Vevey and nearby Clarens as the setting of his 1759 novel, Julie, ou la Nouvelle Héloïse.

Rousseau’s writings made an impression on Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, who visited the lake and Vevey in 1816. Byron wrote “The Prisoner of Chillon” in Ouchy, inspired by the castle on the lake just six miles east of Vevey. Mary Shelley’s inspiration for her novel Frankenstein: or, The Modern Prometheus came during this same trip. Following the Romantics recasting of the Alps, tourism increased dramatically, and the re-imagination of the region that had begun while Reynier still lived there was complete.3

Figure 1.1. View of Vevey on Lake Geneva and its Alpine surroundings. Jean-François Reynier was born and grew up here. Engraving, Johann Ludwig Aberli (1723–86), 1772. Courtesy of the Musée historique de Vevey, Switzerland.

The large Reynier clan had come to Vevey from France as religious refugees fleeing persecution at the end of the seventeenth century. After the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, Jean-François’s grandparents, his young father, and an uncle fled from Beaumont en Diois in Dauphiné (about seventy-five miles south of Grenoble) to Château Neuf d’Isère, near Valence. In 1693, they moved to Lake Geneva, and five years later they finally settled down in Vevey, along with about 900 other Huguenot refugees, who swelled the town’s population to 3,000. In 1701, the city council awarded Jean-François’s grandfather, a lawyer (avocat gradué) named Grève Reynier, the rank of bourgeois de la seconde classe (town citizen, second class) in exchange for a fee of 200 livres. It was a new rank that granted some privileges to him and other newly arriving Huguenot refugees, who stimulated industrial and commercial development in the area. About this time, Grève’s son Pierre married a woman named Jeanne-Marguerite Provensal. Pierre became a prosperous apothecary, pharmacist, and manufacturer with the rank of bourgeois himself. Pierre and Jeanne-Marguerite raised a large family in Vevey. Many of their descendants became well known in the scientific and medical fields, and one became a general in Napoleon’s army4 (see Appendix for the Reynier family genealogy).

Figure 1.2. View of the town of Vevey, from the south. Watercolor, Mérigot, 1777. Courtesy of the Musée historique de Vevey, Switzerland.

Jeanne-Marguerite Provensal Reynier gave birth to Jean-François, her ninth of twelve children, on 17 July 1712, only one event in a familiar but difficult cycle of events for her. Vevey’s new minister, Vincent Perret Doyen, baptized the boy three days later in the Church of St. Martin, a towering twelfth-century landmark in the centre ville. Madame Reynier asked her friends Jean Ausset and his wife and Madame la Venue Gertier to be the godparents. From 1702 to 1716, Madame Reynier was constantly pregnant, caring for a newborn, or coping with the loss of a small child. She and Pierre had at least ten children during this time, only five of which reached adulthood. Jean-François was the fourth that did not die within ten months. Madame Reynier grew up fleeing persecution, led a life of travail as a wife and mother in this beautiful Alpine setting, and then died before her sixtieth year.

The town in which the Reyniers chose to live was an old one. Although Vevey had not fully recovered from a fire in 1688 that took many lives and destroyed 230 buildings, the medieval wall and a half dozen of the old city gates were still there when Jean-François was growing up. Above the town stood a twelfth-century castle called Blonay. Adjacent to Vevey stood the La Tour de Peilz castle, which had lain in ruins since its destruction in the fifteenth century but would soon be rebuilt. Although beautiful and serene, the lake could also bring destruction, as it did in the flood of 1726, which submerged houses, cellars, gardens, wine presses, and other buildings in the lower parts of the town under eight feet of water.5

While Jean-François was growing up, Vevey fell under the political regime of Bern, and relations were at times tense. Bern took the town and its environs from the Savoyards in 1536 and ushered in the Reformation. While the majority of the populace accepted the Calvinist faith, many resented the harsh regimen under the Bernese, which included compulsory military service for males aged sixteen to sixty. Alarms and threats from enemies were frequent in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and a small fleet sailed from Morges to protect the Swiss port towns from Savoyan raids. Vevey and surrounding areas contributed two companies with nearly 200 men for defense. In 1656, they fought in the unsuccessful war against the Catholic Villmergen regime in Canton Aargau, and in 1712 (the year of Reynier’s birth), they suffered heavy casualties in the second war against Villmergen, although they won and therewith ensured Protestant hegemony in the Swiss cantons. Strict discipline in the military and other problems led to a mutiny by Vevey’s troops in 1743, which the regime put down harshly.6

The people in and around Vevey had traditionally maintained a largely subsistence economy based on cattle and sheep farming, but this changed rapidly in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, largely due to the influx of Huguenot refugees like the Reyniers. The refugees built woolen cloth, fabric, clothing, silk stocking, and dying factories, as well as tanneries and other industries. Refugees from Dauphiné and Languedoc dramatically expanded wine production, which inhabitants began consuming so heavily that it became part of the salary of some public employees. Huguenots also fostered public gardens, vegetable gardens, and fruit trees in and around Vevey, and they established a warehouse system throughout the canton that facilitated a larger trade in agricultural goods. The commercial-manufacturing development that began about the time the Reynier family settled in Vevey continued after Jean-François’s departure for America a generation later. By 1763, thirty-one shopkeepers sold sugar, coffee, bonnets, wooden shoes, and wool, and the town had seven tanners, three chamois makers, one glover, one shovel maker, three saddler makers, one britches maker, twenty-nine watch and clock makers, five “polishers” (polisseurs, for the watches), six comb manufacturers, three lace makers, three stocking makers, and twenty-two coopers.7

Pierre Reynier was involved in manufactures until his death in 1721,8 but he and many of his descendants contributed to the economic transformation of the area more significantly through their endeavors in the medical field. The Reyniers and other Huguenots joined the native doctors, pharmacists, and apothecaries in their struggles against the numerous epidemics that struck Vevey in the early eighteenth century (such as dysentery and petechial), and they strove to improve public health generally in an era of rising mortality. In Vevey, significant tension existed between refugee and native practitioners during Jean-François’s youth, which he witnessed because of his family’s involvement. In addition to his father’s work, Jean-François’s brothers Jean-Pierre and Jean-Abram Reynier ran one of five apothecaries in Vevey, although this was shortly after his departure. Later his nephew, Jacques-François Reynier, worked without compensation in a charity hospital that treated destitute refugees and served on its board of directors. Informal medicine and the tendency to combine medical practice with other economic endeavors were common, as the Reynier family profile shows.

Pierre and Jeanne-Marguerite Reynier provided a privileged, relatively safe life for Jean-François and the rest of their large family. Jean-François grew up in their second-class bourgeois household with a lot of brothers and sisters and probably one or two servants. Numerous cousins, an aunt and uncle, and perhaps his grandparents lived nearby. He was well schooled and proud of it. In addition to formal schooling, his father and other family members taught him something about medical practice and how to combine it with other economic efforts. Jean-François was aware of the violence and religious troubles his parents and grandparents had experienced in France, but now the family belonged to the state church, and he was thankful that they no longer endured persecutions.9

While growing up in this privileged, stable home in Vevey, Jean-François became disillusioned with the state of affairs in the Church of St. Martin and began attending spiritual meetings at the home of an unusual, charismatic woman named Madame de Warens. It is unclear whether his family approved, but they probably did at least initially. Before his death in 1721, Pierre had stimulated an interest in medicine in his son, and de Warens’s interest in informal medicine attracted Jean-François to the group. According to her star pupil, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, she had learned philosophy and physics informally and practiced alchemy and empirical medicine in Vevey during the 1720s, preparing elixirs, tinctures, and balsams, some with “magical” properties. This was an unusual collection of interests for a bright and charming noblewoman, who became a leader of the town’s pietist enclave. The young Reynier learned valuable lessons from her about alternative spirituality and medical practice, which he later applied in the Americas.10

Madame de Warens’s spiritual enclave was part of an international religious movement, a pietist wave sweeping throughout Protestant Europe and eventually many American colonies. Since the second half of the seventeenth century, perhaps earlier, many Protestants, disillusioned with their state churches’ emphasis on dogma, confessionalism, and intolerance, initiated a spiritual renewal movement. In order to complete the work of the Reformation, they wished to achieve a fully spiritual life at the individual and community levels. Among their many goals, they wanted to achieve a spiritual rebirth, live the rest of their lives piously, reform society to make it more godly, and spread the Gospel to others (including non-European peoples).

Pietists tried to reform themselves and society in many ways, some of which were contradictory. Some sought to separate from the confessional churches, which they viewed as the biblical “whore of Babylon,” while others fought hard to stay within the church in order to reform it or to avoid marginalization and persecution. Some of the separatists were hermetic, meaning they turned their backs on a corrupt world and sought to worship as they saw fit: alone or in small, isolated groups. Others followed the philadelphian principle of separating from the fallen confessional churches and then seeking the like-minded in order to unite and form the true church of brotherly and sisterly love. In some cases, these groups believed that they must do so before the pending Apocalypse. Some pietists promoted a spiritually ecstatic, enthusiastic, and confrontational style, while others were “quietist,” meaning they contemplated the truth and reformed themselves, silently experiencing the work of the Holy Spirit from within and enduring the imperfections and corruptness of the world and its state churches.

Important to the pietist wave were the controversial beliefs and practices of its members regarding marriage, sexuality, women, and gender. Women played a high-profile role in many pietist groups. Many noble women were be...