eBook - ePub

Domingos Álvares, African Healing, and the Intellectual History of the Atlantic World

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Domingos Álvares, African Healing, and the Intellectual History of the Atlantic World

About this book

Between 1730 and 1750, powerful healer and vodun priest Domingos Álvares traversed the colonial Atlantic world like few Africans of his time — from Africa to South America to Europe — addressing the profound alienation of warfare, capitalism, and the African slave trade through the language of health and healing. In Domingos Álvares, African Healing, and the Intellectual History of the Atlantic World, James H. Sweet finds dramatic means for unfolding a history of the eighteenth-century Atlantic world in which healing, religion, kinship, and political subversion were intimately connected.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Dahomey

You have nearly all the people of this family in your country. They knew too much magic. We sold them because they made too much trouble.

—Dahomean informant remembering why a certain clan was sold away to slavery in the Americas, 1930s, quoted in Melville J. Herskovits, Dahomey: An Ancient West African Kingdom

In late March 1727, English ship captain William Snelgrave steered the galley Katherine toward the shore near the West African port of Ouidah with the intention of purchasing slaves. Snelgrave, a veteran captain of more than twenty years, had traded extensively at Ouidah, most recently in 1720. Upon anchoring his ship and forging the several miles inland to the English fort, he discovered a “dismal” scene. The land was decimated, buildings burned, and fields strewn with human remains. Just three weeks earlier, the army of Dahomey had overrun the port city. In the ensuing chaos, thousands of people fled. Others were captured and made prisoners of war. Among the prisoners were “about forty . . . white Men, English, French, Dutch and Portuguese,” who occupied the various European forts at Ouidah. After being marched nearly forty miles inland to Allada, one of the European prisoners, the governor of the Royal African Company, was given an audience with the king of Dahomey, Agaja. Apologizing for the inconveniences suffered by the Europeans, Agaja explained that “he was very sorry for what had happen’d, for he had given Orders to his Captains . . . to use the white Men well; but he hoped they would excuse what had befallen them, which was to be attributed to the Fate of War: Confessing, he was much surprized when he was first informed, so many white People were made Prisoners, and soon after brought to his Camp. That in the Confusion of Things he had not regarded them so much as he ought; but for the future, they should have better Treatment.”

The Europeans returned to their forts, where Snelgrave found them in a miserable and uncertain state. Assessing the situation, Snelgrave decided there was little hope for conducting business at Ouidah. The Katherinelifted anchor and sailed twenty miles down the coast to the port of Jakin, arriving on the morning of April 3. Snelgrave had not conducted business in Jakin before, but he knew its bad reputation. All details of the trading arrangement needed to be established before Snelgrave went ashore since the ruler of Jakin “had formerly plaid base Tricks with some Europeans, who had not taken such a Precaution.” In order to secure his interests, Snelgrave sent the ship’s surgeon ashore to negotiate the terms of trade. By nightfall, an agreement was reached and Snelgrave retired to a house that would serve as his trading factory.

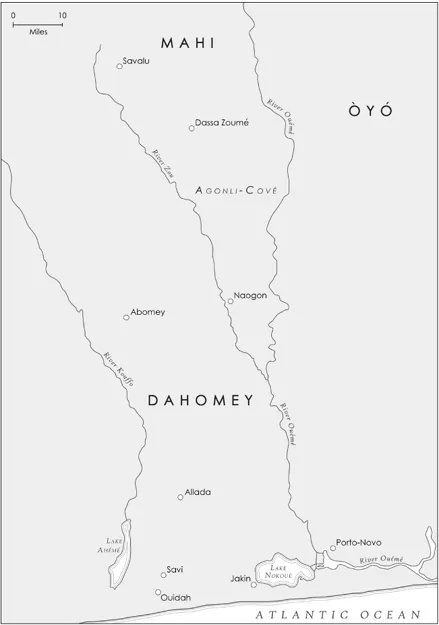

MAP 1.1 Dahomey, Òyó, and Mahi. Map created by the University of Wisconsin Cartography Lab.

The following day, on April 4, a royal messenger arrived at Snelgrave’s door inviting him to meet with King Agaja at his camp in Allada. Given what he had witnessed at Ouidah, Snelgrave received Agaja’s invitation with trepidation. He said that he would consider the proposal and provide a response the following day. Recognizing Snelgrave’s unease, the messenger threatened that if he did not go to Allada, “he would highly offend the King” and would “not be permitted to trade, besides other bad Consequences [that] might follow.” Four days later Snelgrave abandoned his camp at Jakin and struck out for Allada. Over the course of two days, Snelgrave rode more than forty miles in a hammock carried by a team of twelve servants. Accompanying Snelgrave were the Duke of Jakin and a Dutch captain, also in hammocks, “which is the usual way of travelling in this Country for Gentlemen either white or black.” A retinue of 100 slaves attended to the men’s needs. As they traveled, Snelgrave again witnessed the carnage of war—the burned-out remains of towns and villages, bones littered across the fields.

Immediately upon arriving in Allada, Snelgrave was greatly perturbed by the numerous flies that swarmed the area. Though he was given several servants to keep the flies away when he was eating, he observed that “it was hardly possible to put a bit of Meat into our Mouths without some of those Vermin with it.” The source of these flies was a mystery to Snelgrave until later that afternoon, when, approaching the king’s gate, he saw “two large Stages, on which were heaped a great number of dead Men’s Heads, that afforded no pleasing sight or smell.” Snelgrave’s interpreter informed him that these were the heads of 4,000 Huedas who had been sacrificed by the Dahomeans to their “God” as gratitude for their victory at Ouidah. The following evening, Snelgrave witnessed the arrival of yet more prisoners of war, 1,800 “Tuffoes” brought before Agaja to determine their fate. Many were sacrificed in the same manner as the 4,000 Huedas. Others were kept as slaves for Agaja’s own use. And still others were reserved for sale to Europeans. In a public ceremony, Agaja’s soldiers received 800 cowry shells for each male prisoner of war; for women and children, 400 cowries each. In addition, soldiers received 200 cowries for each enemy head they returned.1 Snelgrave claimed that some soldiers appeared at the court with “three, or more Heads hanging on a String.” Over time, these amounted to thousands of skulls that Agaja collected with “designs to build a Monument with them.”

After several days in Allada, Snelgrave met with Agaja and expressed his desire to “fill my ship with Negroes; by which means I should return into my own Country in a short time; where I should make known how great and powerful a King I had seen.” Agaja agreed that he would trade, but not before settling on a “Custom,” or fee to conduct trade. Snelgrave cleverly argued that because Agaja was a “far greater Prince” than King Huffon of Ouidah, he should not command a fee as high as that which was customary under Hueda rule. Agaja retorted that “as he was a greater Prince, he might reasonably expect the more Custom,” but since Snelgrave was the first English captain to arrive after the conquest of Ouidah, he would treat him “as a young Wife or Bride, who must be denied nothing at first.” Snelgrave was asked to name his price and eventually requested a fee one-half of that previously charged by Huffon. Moreover, he asked that the king deliver three male slaves for every female and that he be given the right to reject any slaves that he found unfit. Agaja agreed, noting that he “designed to make Trade flourish” and that he would “protect the Europeans that came to his Country.” Over the next several months, some 600 slaves were dispatched from Allada to Jakin, until Snelgrave finally filled the Katherine’s 300-ton hull. On July 1, 1727, the Katherine set sail for Antigua. During the seventeen-week passage, 50 of the enslaved Africans died from disease, dehydration, and malnutrition. The remaining 550 of Agaja’s prisoners of war began their new lives as Caribbean slaves, cultivating cane to fulfill England’s insatiable desire for sugar.2

Dahomey’s conquest of Ouidah represents the apex of its military power under Agaja. Its army was the best-trained, best-equipped military in the region, consisting of 10,000 regular troops, as well as various apprentices, servants, and hangers-on. In addition to its victory over Ouidah, it had already conquered Weme (1710s) and Allada (1724). Agaja, who had been military commander under the former king (his brother, Akaba), was proud of his accomplishments in propelling Dahomey to regional dominance. In recounting his military prowess, Agaja told several Europeans that his father and grandfather had fought fewer than a dozen battles combined. His brother had fought only 79 battles. He, on the other hand, had fought more than 200 battles and was still counting.3

The victory at Ouidah was particularly gratifying for Agaja, in no small part because it provided Dahomey with direct access to the spoils of European trade. No longer would Dahomey have to accede to the wishes of Hueda middlemen. As Agaja’s exchange with Snelgrave illustrates, Dahomey was eager to cultivate good relations with its European counterparts, but consolidation of the victory at Ouidah would prove to be much more difficult than Agaja anticipated. The early promise of easy wealth was thwarted by years of warfare and disruptions in the interior. The exiled Hueda, who fled to the west during the 1727 invasion, continued to contest Dahomean supremacy at Ouidah. More ominous still was the Kingdom of Òyó, the Yoruba-speaking kingdom to the northeast of Dahomey whose mounted cavalry struck fear into even the most hardened Dahomean soldiers. Just one year before Dahomey took Ouidah, Òyó had invaded Dahomey, killed and enslaved large numbers of soldiers, and burned the capital city of Abomey to the ground, forcing Agaja to flee to the bush. Agaja attempted to enter into negotiations with Òyó in 1727, but these negotiations failed. Beginning in 1728 and continuing for three years, Òyó marched on Dahomey every dry season in an attempt to overthrow Agaja. In 1728 and 1729, Òyó troops were thwarted in their attempts to take the Dahomean capital, and they retreated north in order to avoid the floods of the rainy season. By 1730, however, Òyó conquered Abomey, forcing Agaja to transfer his capital to Allada. The Kingdom of Òyó would remain a thorn in Agaja’s side for years to come, occupying his attentions in the north even as rivals in the south conspired to cut him out of the trade with Europeans.

The accounts of Europeans in Agaja’s court are well known to historians.4 So too are the contours of the political and military history that propelled Dahomey into a regional power in the first half of the eighteenth century.5 Less well known are the impacts of warfare and slavery on those who were the victims of Agaja’s military aggression. The overwhelming emphasis in European accounts of Dahomean military expansion rests on the savagery of the aggressors: fields scattered with bones, heads on strings, and gruesome scenes of human sacrifice. To be sure, this bloodshed and killing are important for understanding the dynamics of political power in the region, but violence was also critical in shaping the social and cultural identities of people. Peoples displaced by violence often reconstituted themselves in alliance with others in similar circumstances. These exile societies were multilingual, polytheistic, and ethnically heterogeneous. Nevertheless, they usually spoke a common lingua franca, shared religious ideas, and sought common ways to resist the overwhelming power of Dahomey. As such, these new identities born of violence could be grafted onto those identities that were already very much regional in character.

The foundation of this regional culture emerged out of a series of migrations that began around the year 1000 c.e., continuing through the period of Agaja. The result of these overlapping migrations was a confluence of Ewe, Adja, Fon, Gun, and proto-Yoruba into a contiguous cultural area with a broadly shared linguistic structure (Gbe-speaking), shared sense of lineage and history (through the ancestral homeland at Tado, in present-day Togo), and shared religious system (centered on vodun). Geographically, this region was bounded roughly by the Volta River in the west and the Ouémé River in the east, although these boundaries were porous, allowing for the influx of strong Yoruba influences from the east and Islamic influences from the north. The horrific violence of the 1700s is a reminder that we should take care not to confuse cultural similarity with political cohesion. Nevertheless, it seems clear that migration, trade, and warfare had facilitated shared sociocultural affinities among peoples, even if they did not necessarily conceive of themselves as sharing a common “identity.” In short, the Gbe-speaking region was, at the same time, culturally similar and politically heterogeneous prior to the arrival of Europeans.6

European commerce increased the pace of social and cultural exchange, as the demand for slaves transformed local economic and political configurations. The Portuguese established regular trade in the region in the sixteenth century. By the end of the seventeenth century, the Dutch, English, and French also exchanged goods along the coast. Europeans delivered cowry shells (from the Indian Ocean), iron bars, guns, tobacco, rum, and linen in exchange for gold, small quantities of palm oil and ivory, and thousands of slaves. In the 1690s, roughly 10,000 slaves a year left the Bight of Benin, and by the first decades of the eighteenth century, the trade peaked at more than 18,000 souls exported annually.7 Overall, an estimated 400,000 Africans departed the Slave Coast between 1700 and 1725, more than from any other region in Africa.8 Trade on such a massive scale drew attention well beyond the immediate coastline. In the early 1700s, Islamic merchants from the far northern interior purportedly traveled three months on horseback in order to trade slaves at Ouidah and Jakin.9 By 1715, one French trader stated that between twenty and thirty different African nationalities were sold at Ouidah.10

Though Ouidah was the hub for the region’s economic expansion and the epicenter of cultural exchange, the impacts of these transformations reverberated deep into the interior. Nowhere were these changes felt more than in the region of Agonli-Cové, sixty miles from the coast. Situated halfway between the Yoruba kingdom at Ketu and the Fon at Abomey, Agonli-Cové had long been a cultural crossroads. Not only was it a way station for east-west Fon and Yoruba migrations that had been ongoing for hundreds of years, but its location near the confluence of the Ouémé and Zou Rivers meant that people and goods from as far north as the Niger River tributaries could easily reach the area. During the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, the region never fell under the full dominion of either the Yoruba or the Fon kingdom. Indeed, the area from Agonli-Cové north to Dassa and Savé was something of a political no-man’s-land. Eighteenth-century observers described the region as a series of “independent states” set “amongst their Mountains and Woods.”11 However, with the rise of Dahomean militarism and empire, these acephalous groups eventually united into a “confederacy” that came to be known as “Mahi.”12

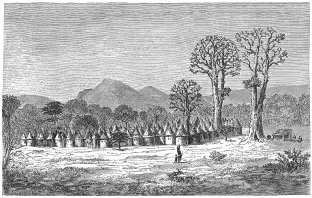

“A Mahi Village.” Lithograph from J. A. Skertchly, Dahomey as It Is; Being a Narrative of Eight Months’ Residence in That Country . . . (London: Chapman and Hall, 1874).

The word “Mahi” (or “Malli,” “Maki,” “Maxi”) was a Fon term of derision used by the kings of Dahomey to describe all of the inhabitants of the region between Dahomey and Òyó. It can be translated roughly as “those who divide the market” or “those who revolt.”13 The term first appeared in European documents in 1732, coinciding roughly with the Dahomean army’s first major assaults on the region.14 Caught in the middle of the Dahomey-Òyó disputes of the late 1720s, the diffuse peoples of Mahi found themselves at the geographic center of a protracted war. The loose social and political structures of these peoples made them particularly vulnerable to enslavement. Thus, Mahi was considered “ideal terrain for slave hunting.”15 Though the Mahi retained cultural allegiances to the Gbe-speaking peoples, they, along with the Òyó and many others on the Slave Coast, feared Dahomey’s increasing power and rejected the legitimacy of their conquests of Allada and Ouidah. By 1730, many Mahi, including the peoples of the Agonli-Cové region, entered into an alliance with Òyó. This alliance was, quite possibly, the determining factor in Òyó’s ability to finally take Abomey, forcing Agaja to flee to Allada. In retaliation, Agaja sent his army into Mahi territory in May 1731, and it remained there until March 1732. During these raids, many villages were destroyed. The survivors were enslaved or became refugees, fleeing northward, where they eventually entered into an alliance with the Jagun, a Yoruba dynastic group centered at Yaka. This alliance of exiles became part of the “Mahi confederacy.” Thus, “Mahi” was transformed from a term of derision into a marker of mutual protection, an “ethnic” identity born in the fires of war, in resistance to the privations wrought...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Domingos Álvares, African Healing, and the Intellectual History of the Atlantic World

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations, Maps, and Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Dahomey

- 2 Passages

- 3 Recife

- 4 Rio de Janeiro

- 5 Freedom

- 6 The Politics of Healing

- 7 Dislocations

- 8 Inquisition

- 9 Algarve

- 10 Obscurity

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Domingos Álvares, African Healing, and the Intellectual History of the Atlantic World by James H. Sweet in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.