![]()

PART I

Conceptions and Sources

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Taking the Measure of the Ancient World*

Almost exactly forty years ago, I was in my last term at a Scottish public school on the shores of the Firth of Forth, where the climate would have made that of Durham, by comparison, seem positively tropical, and the boys were prevented from freezing only by being permanently occupied in playing rugby football. But, fundamental as rugby football (“rugger” in common language) was to the ideology of the school, even I was surprised when the then head boy approached me, and said in despairing tones: “Millar, I get depressed sometimes. There are some people in this school who think that rugger is just something like Latin, which you never think about except when you’re doing it.”

I do not tell this story in order to mock my own origins. For one thing, in a world where we can be told by our prime minister that there is “no such thing as society,” the values of “team spirit” and mutual responsibility which Loretto really did instil now seem less self-evident, and more important, than they might have done. Secondly, when, with the onset of the second infantilism common to middle-aged gentlemen, I came back years later to watching international rugger matches, I realised that the head boy had been right, on one side at least: we had just played and played, without actually thinking about how the game might be played better.

So, thirdly, might he have been right also in implying that Latin was also something which one tended just to “do,” and that we do not always ask ourselves what our subject is, what it really amounts to, or how are we or our pupils might best approach it? This is the opportunity which I would like to take now: not, at least in the first instance, by way of self-questioning and self-criticism, but rather the opposite. By defining what our subject amounts to, we might also remind ourselves, and others, just how vast its scope is.

Let me begin by offering a possible definition: classics is the study of the culture, in the widest sense, of any population using Greek and Latin, from the beginning to (say) the Islamic invasions of the seventh century A.D.

Since Michael Ventris’ decipherment of Linear B, “the beginnings” ought of course to cover the later second millennium B.C.; and certainly we can on no account leave the late Bronze Age out of our conception of Greek history. None the less, we could still choose to treat that as a sort of Greek “prehistory,” and to take the decisive beginning as falling in the eighth century B.C. To do that would be to use two interrelated markers: the appearance of the earliest scraps of writing which are not only in Greek but in the Greek alphabet; and the works of Homer and Hesiod.

Whether we ought, or ought not, to talk of a real, historical world of Homer (following M. I. Finley’s brilliant The World of Odysseus), it remains very important that a remarkable range of the basic features of Greek culture and Greek social and political life is already represented for us in the poems of Homer: a multiplicity of gods and goddesses; sacrifices offered to them; temples; cities, and newly founded “colonial” cities; war; competition; honour; oratory; popular assemblies; competitive sport. Thus the history of European sports journalism begins, very appropriately, with Iliad 23, and a famous row as to whether victory in a chariot race had been legitimately won. (Perhaps, in view of the farce of the Grand National in 1993, the Classical Association could offer a prize for fifty lines of Homeric hexameters describing a race which never got started because some deity maliciously dulled the wits of the officials?).

But if we are to begin with Homer, it is absolutely essential not to let that mislead us into thinking of “Greek history” as something which happened first, followed sometime after by “Roman history.” For the two histories and the two cultures were closely connected from the eighth century onwards, and became even more inextricably intertwined as time went on. Thus, we must recall that imported Greek vases were already reaching Rome around the notional, or legendary, date of its “foundation,” 753 B.C. And from around that time too we have the East Greek Geometric skyphos discovered on the island of Pithekoussai (Ischia), the earliest Greek settlement in the West, and not much over one hundred miles from Rome. The famous graffito written on it, “I [am] the cup of Nestor, good to drink from,” both reflects a knowledge of epic, and, being written from right to left, illustrates the (probably very recent) borrowing of the Greek alphabet from Phoenicia. Almost all that we can hope to know of the eighth-century Mediterranean is embodied in a single fragmentary pot.

We come, however, a great deal closer to early Rome with the krater of the following century found at Caere, a mere twenty miles from Rome, painted with a scene showing Odysseus and his companions blinding Polyphemus; or, a century later again, with Herodotus’ story (1, 167) of how a Greek

agn was instituted at Caere (Agylla) on the instructions of Delphi, in expiation for the murder of some Phocaean captives, and was still maintained in the next century. It is not merely that the early evolution of Rome took place within the orbit of Greek culture, as that the preconditions for the Romans’ self-perception of themselves as descended from Aeneas existed almost from the very beginning.

From the archaic period onwards, we have to see Greek and Roman culture as evolving in parallel. Rome did lag behind, of course. Greek cities dotted the eastern and western Mediterranean, and the Black Sea, several centuries before Roman expansion began. Moreover, and crucially for our knowledge, Roman literature begins some five centuries later than Greek. The fact is more surprising than one might think. Rome of the late sixth century was already a major city, with at least one massive temple on the Capitol. And if the inscription, in an early form of Latin, on the Lapis Niger from the Forum is really of the mid-sixth century, then it is earlier than any known public inscription from Athens. Why a Latin literature did not develop before the third century B.C. is a real puzzle.

The moment when the two linked but separate histories do really start to become one is the late fourth century B.C. For Philip and Alexander’s conquests, carrying Macedonian armies into Greece, and Greek-speaking armies all over the Near East, Egypt, Babylonia, Persia, and central Asia, are exactly paralleled by smaller-scale, but even more significant, developments in Italy. I mean the break-up of the Latin league in 338 B.C., and then half a century of wars against Samnites, Etruscans, Celts, and Greeks. Even before the Romans crossed the Straits of Sicily in 264 B.C., a long list of Greek cities had already come under Roman domination, and Rome was already a known power on the edges of the Greek world.

We do have to accept that both the interweaving of Greek and Roman culture and history, to produce a single “Graeco-Roman” world, and the vast extension of that world were produced by imperialism and colonisation. However complex the accompanying factors, and the mutual reactions between different cultural groups, it was, quite simply, imperialism and the desire for conquest which carried Greek culture to Afghanistan and northern India, and Graeco-Roman culture to Hadrian’s Wall. As I am trying to stress, we have everything to boast of in the sheer extensiveness, in space and in time, of Graeco-Roman culture. But in emphasising the importance of our field as a major part of human experience, we must not, just because both “imperialism” and “colonialism” are unpopular concepts in modern culture, falsify history by obscuring the fact that it was, in the first instance, war, conquest, and overseas settlement, both Greek and Roman, which created the vast and long-standing Graeco-Roman world.

As for that process itself, we do not need to follow all the details here. It will be enough to recall that the two major phases were indeed Alexander’s conquests in Asia in the later fourth century, and Roman conquest, in both the Greek East and what was to become the Latin West, which reached a decisive phase in the first century B.C.

From within the context of the imposition of Greek culture in Asia, it will be worth just picking out three areas where the consequences were particularly striking. The first is Egypt, which is given a particular significance by the survival of papyri. So, firstly, we can actually meet the settlers from the Greek world who established themselves there from the late fourth century onwards. Perhaps most notable of all, because so early, is the Greek papyrus of 311 B.C. from Elephantine, nearly six hundred miles south from the mouth of the Nile. The papyrus records a marriage contract between two Greek settlers:

More important, perhaps, because from now on until the Arab conquests Egypt was to be a bilingual land, in which both Egyptian and Greek were used, the tens of thousands of surviving papyri preserve for us a large, if erratic, cross-section of Greek literature, in which Homer predominates above all else. We can now read Greek (and a little Latin) literature, not as transmitted by medieval scribes, but as read in the ancient world.

The second area of immense significance was of course Judaea, for one of the long-term consequences of Alexander’s conquests was to be that post-biblical Judaism, and of course early Christianity, would be formed within a Greek environment. Looking back from the end of the first century A.D., the great Jewish historian Josephus, writing in Greek the whole history of his people from the Creation to A.D. 66, was to incorporate a wonderful folk-tale, or (one might say) historical novella, about Alexander’s visit to Jerusalem:

We need not hesitate to say that the story as told is legend, for the Book of Daniel, in which this pseudo-prophecy does indeed appear (8:21), had not yet been written. It was to be composed, in the form in which we have it, in the heart of the Hellenistic period, to be precise in the 160s B.C., during the persecution of Judaism by the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes.

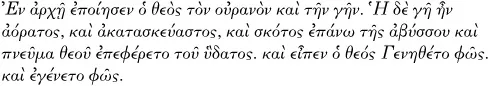

Alone of all the other cultures which were to be submerged by Greek culture, Judaism continued to produce works written in its two native languages, Hebrew and Aramaic (Daniel uses both), and to have its own canonical works translated into Greek. The legend of how the Bible, or at least the Pentateuch, came to be translated into Greek, involves both Egypt, under Ptolemy II Philadelphus (283–246 B.C.), and Judaea. For the king is said to have sent a mission to Jerusalem to bring translators to carry out the work in Alexandria. The story does indeed seem to be legend, though the seventy (or seventy-two) translators have given its name to the Greek version of the Bible, the Septuagint. But it is a fact that the work of translation had at least been begun in the third century; and with it a quite new vision of the world, and how it came into existence, came to be expressed in Greek. How many classes for the translation of Greek prose, I wonder, have ever found before them the opening words of the first chapter of Genesis?

Yet this view of the nature of the world and of the divinity was, as time went on, to be at least as important, for millions of people whose language of culture was Greek—and later, as we will see, Latin—as anything contained in the pagan classics. It is therefore essential for us to see it too as part of ancient culture. The third century was thus also the moment when the two strands of our inherited culture came together.

Before we go on to look at the later Graeco-Roman world, it is worth taking a glance sideways at another conjunction of cultures and religious systems which might have led to an equally long-lasting new civilisation, but in the end did not. In the time of Ptolemy Philadelphus large parts of India and Afghanistan, profoundly affected by the arrival of Alexander, but given up by Seleucus Nicator, were ruled by a great emperor of the Mauryan dynasty, Asoka, one of whose epithets was “piodasses,” which apparently means “of benevolent countenance.” Having an important message to communicate to his people, Asoka had a series of proclamations inscribed at different points ac...