- 584 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

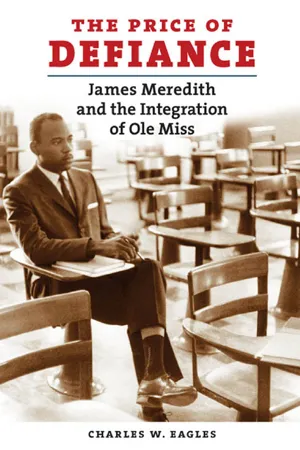

When James Meredith enrolled as the first African American student at the University of Mississippi in 1962, the resulting riots produced more casualties than any other clash of the civil rights era. Eagles shows that the violence resulted from the university's and the state's long defiance of the civil rights movement and federal law. Ultimately, the price of such behavior — the price of defiance — was not only the murderous riot that rocked the nation and almost closed the university but also the nation's enduring scorn for Ole Miss and Mississippi. Eagles paints a remarkable portrait of Meredith himself by describing his unusual family background, his personal values, and his service in the U.S. Air Force, all of which prepared him for his experience at Ole Miss.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Price of Defiance by Charles W. Eagles in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Higher Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE Ole Miss and Race

1. “Welcome to Ole Miss, Where Everybody Speaks”

At the start of the 1960 football season, Sports Illustrated featured a full-page color photograph of a beautiful young woman and a handsome football player strolling hand in hand across the University of Mississippi campus.1 Although many colleges had pretty women and good-looking male athletes, the article’s title, “Babes, Brutes, and Ole Miss,” seemed more applicable to Ole Miss than to its competitors. Sports Illustrated had captured in a single image the university’s national reputation: it was, as the caption suggested, home to “the best of both worlds,” beauty queens and winning football teams.2

The university’s renown received powerful confirmation in September 1958 when senior Mary Ann Mobley became the first Mississippian to win the Miss America beauty pageant. She had the year before finished second in the Miss Mississippi contest and earlier had been selected as National Football Queen, State Forestry Queen, and State Travel Queen. Mobley, an excellent student, came to the university in 1955 in the first group of prestigious Carrier Scholars, and she served as an officer in student government and had been selected for Mortar Board, an honorary leadership group. A trained singer, dancer, and model, the “brown-haired Southern belle” sang a medley of operatic and popular songs and performed a modern jazz dance for the Miss America judges and a national television audience. Her selection thrilled Mississippi. After a spontaneous street party by three thousand people that lasted past midnight in her small hometown of Brandon, Mayor John McLaurin said being Miss America’s mayor was a special honor, and he praised the little girl he had watched grow up. One Mississippian declared her selection “the best thing that had happened to Mississippi since the South won the first Battle of Bull Run.”3

One year later, the day after the Miss America pageant, the Jackson Clarion-Ledger’s front page proudly announced, “The Miss America crown stays in Mississippi.” Outgoing queen Mary Ann Mobley crowned Lynda Lee Mead of Natchez as Miss America for 1960. For the first time in more than twenty years, the crown remained in the same state, and for the fifth time in ten years a southern girl was named Miss America. Not only were Mobley and Mead fellow students, they also were sorority sisters in Chi Omega. Once again the campus, as well as the rest of the state, went “wild over Lynda’s victory,” with perhaps the biggest celebration at the Chi Omega house. The chapter president said her sorority sisters were “overjoyed and just happy.” Mead’s selection particularly pleased the campus because she had started out as Miss University. Two weeks after her crowning, the proud student newspaper ran four extra pages of stories and pictures of the school’s second Miss America. A Jackson newspaper columnist boasted, “Mississippi may be last in a lot of things, but we can cite to the world that we are first in womanhood!”4

Although the university had gained national fame for its beautiful women, the emphasis on female beauty ran deeper than two Miss Americas. Each year after World War II, dozens competed in the Miss University pageant and others entered contests in towns across the state and the South. Eight times between 1948 and 1961, a student had been crowned Miss Mississippi, and twice in the late 1940s the university had hosted the state contest. In 1961, for the fourth consecutive year, an Ole Miss student went to Atlantic City as Miss Mississippi, and for the first time women from Ole Miss also represented Missouri and Tennessee.5

Beauty and beauty contests had long formed an integral part of student life at the university. In 1909 students first elected the most beautiful woman, and in 1918 the yearbook began including a “Parade of Beauties.” The yearbook also perennially displayed dozens of photographs of pretty girls chosen by various groups as queens, favorites, and sponsors. The competition could be keen: a month after the second Chi Omega was crowned Miss America, the student newspaper carried a lengthy article about beauty titles held by the new pledges of Delta Delta Delta to prove that their sorority “isn’t short on beauty either.” One Tri-Delt was Mississippi’s Miss Hospitality, Miss Franklin County, and Forestry Queen for 1957, while another reportedly, and importantly, had “probably won more beauty crowns than any girl on the Ole Miss campus.” Photographs of the young women accompanied the story.6

Other female students, not just the official beauty queens, also routinely impressed visitors to the campus. One concluded that “beauty here is no legend.” Enjoying watching the women, another male guest did not find “one unattractive” woman or one “lacking in taste, in dress or grooming. At least half,” he concluded, were “actually pretty and an astonishing number beautiful.” The “fetching girl students with voices like pearls floating in a dish of cornmeal mush” nearly overwhelmed a reporter from outside Mississippi.7

As the Sports Illustrated photograph suggested, the university’s football teams matched its beauty queens in stimulating school pride and in garnering national recognition for the school. The phenomena of athletes and beauty often intertwined at Ole Miss. The woman in the picture was the daughter of the baseball coach, and she would marry the man in the photograph who was a baseball and football player and who would later serve as the university’s athletic director. One young man who had dated both of the university’s Miss Americas was an Academic All-American football player who would decades later become chancellor of the university.8 Athletics, and particularly football, played an important role at the university.

The Ole Miss Rebels under coach John Vaught established a reputation as a big-time football program. After becoming the Rebels’ head coach in 1947, Vaught compiled the second-best coaching record in major college football. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the Rebels’ golden age, Vaught’s teams reached the pinnacle of collegiate football and, according to one expert, “set a national standard for excellence.” Ole Miss won two Southeastern Conference (SEC) championships and went to five postseason bowl games in the 1950s, and in 1960 they became the national champions with a record of 10–0–1. The Rebels’ achievement was particularly impressive because the teams played relatively few games in Oxford, with “home” games often before larger crowds in Memphis and Jackson.9

Ole Miss football was, however, more than a game on Saturday. One alumnus recalled that, in the late 1950s and early 1960s, “Football transcended almost all else.” For the entire state, college football seemed to dominate each autumn. In 1960 Time described the effects of Rebel football: “Inspired by Ole Miss, the whole state vibrates in a constant football flap. No high school would think of scheduling a game for the time that Vaught’s team is playing; anyone who cannot get over to Oxford for the Ole Miss game listens to it over his radio.” On the Saturdays of home football games, thirty thousand fans descended on the remote small town. Each game was a major social event for the state’s white elite—part reunion, part celebration of their football powerhouse, and part fancy party. In 1961 Ole Miss was the quintessential football school.10

Though Vaught’s teams had great success, Ole Miss athletics included more than gridiron heroics. The Rebel baseball team won SEC championships in 1959 and 1960. Four Rebels made the all-SEC first team. In terms of national renown and popularity within the state, however, football was still king.11

Ole Miss’s national image accurately reflected student life. According to one study of college environments in 1961, the university was “a freewheeling sort of place that fits very well with its newspaper reputation as a home for beauty queens and bowl teams.”12 The national survey confirmed many impressions of observers of the university. For example, the study found that Ole Miss students were generally very friendly and concerned about the welfare of others in their group. The university did, after all, encourage students to meet and speak to each other. At the beginning of the fall semester, special signs greeting students announced, “Welcome to Ole Miss, Where Everybody Speaks,” and the campus paper promoted the school’s reputation as “the friendly University.” The official student handbook claimed Ole Miss’s friendliness made it “unique in the system of great universities.” One observer remarked that “even if they didn’t say much the students spoke politely when spoken to.” In most campus activities, “proper social forms and manners” were important, but the report found “a surface mannerliness” more than a thoroughgoing concern for others.13

Within such a friendly environment of only four thousand on a compact campus, students found teachers approachable and helpful outside of class, and most professors called students by their first names. Group activities, ranging from student government to intramural sports, played a significant role in the students’ daily lives. In all activities, students displayed considerable school spirit and enthusiasm for their campus. The Ole Miss atmosphere probably differed little from that at other state institutions across the nation, while much smaller church-related liberal arts colleges had even friendlier campuses that supported meaningful group activities for their students.14

Compared to other college students, Ole Miss students demonstrated a remarkable lack of interest in intellectual, aesthetic, and humanistic concerns. A New York Times correspondent found few Ole Miss undergraduates had heard of Flaubert, Kierkegaard, Pushkin, Camus, or J. D. Salinger. To defend the university’s intellectual climate, George M. Street, an assistant in public relations, polled a number of full professors and reported that none of them could identify all of the authors, which only proved the students were not so ignorant as the New York writer claimed. Street himself confessed that he had heard of only Camus, Pushkin, and Salinger and had never read any of their works. Similarly, although the Department of Modern Languages regularly screened foreign films with subtitles, few students reported having seen the movies. Describing the university’s cultural life as “barren,” one critic deplored the unavailability, even in Oxford, of a decent bookstore or any magazines other than the most popular. Students showed relatively little interest in serious art, drama, and music, and the campus did not include any examples of stimulating art and architecture among its mostly classical revival–style buildings.15

Despite an apparent lack of emphasis on academics, the university did produce some stellar students in science, business, and the professions. In addition to the designation of several as Woodrow Wilson fellows and Fulbright scholars, the selection of five students as Rhodes scholars between 1950 and 1961 pointed to the institution’s academic strengths.16

In general the academic performance of the student body, however, remained mediocre. In the 1950s one university committee concluded, “The general level of ability of students in the College of Liberal Arts is not high, being at the 45th percentile on national norms for college aptitudes.” The university accepted all white Mississippi high school graduates who had passed the required courses and had the necessary recommendations. Though it warned students from the bottom quartile of their high school classes that college-level work might be challenging, many came anyway only to fail later. One anonymous professor maintained, “We have a lot of students here who are incredibly dumb,” but, he added, “It’s pretty hard to flunk out of this university.” As evidence he cited the belief among some students that “the Lord created the world in six days.” Only lax academic standards allowed the university to retain a sizable enrollment.17

The practical aspects of education and status-oriented activities primarily concerned Ole Miss students. Popular majors in business, education, and the sciences typically focused on specialized learning rather than on a broad liberal education. The prevailing climate valued tangible, concrete information rather than abstractions and theories. Even in the arts and sciences, students often limited their studying to the textbook and, like students elsewhere, avoided rigorous and demanding classes.18

Once on the campus, students learned that grades and serious intellectual activities were not accorded priority and that the university tolerated barely adequate academic performance. Academic rigor simply was not a hallmark of Ole Miss. According to one assessment, the policy of accepting many marginal students “tended to brake the progress of abler students.” Limited state appropriations, a dependence on tuition, and an emphasis on increasing enrollment of less able students retarded any inclination to push for academic excellence. As historian James W. Silver commented, “In a sophomore class of 30, before the end of the first month I’m talking to only five. If the rest don’t bother me, I don’t bother them.”19

Instead, Ole Miss stressed social life, encouraged conformity, and emphasized institutional traditions. The student handbook claimed that “Ole Miss is not only a school of many traditions, but also a tradition itself.” An Ole Miss Rebel became part of “this living tradition” connecting the past with the present. Traditions involved many social activities ranging from fervent support for the athletic teams to party times called Rebelee and Dixie Week. Freshmen had to learn the alma mater, football cheers, and “Dixie.” Hazing of male freshmen included shaving their heads, making them wear blue “Ole Miss” beanies, and compelling basic conformity to Rebel values.20

Belonging to a fraternity or sorority often defined an individual on campus; the first question asked upon meeting a student commonly dealt with his or her Greek affiliation. The Mississippian, the weekly student newspaper, covered the campus social scene, which revolved around the fraternity and sorority parties. Even the popular intramural program depended on sports teams representing Greek organizations. One national study compared the university itself to a large club, and alumnus and journalist Curtis Wilkie (class of 1963) concurred when he recalled that “Ole Miss had the aura of an exclusive club for the planter class.” A visiting journalist offered a similar analysis: “More social than academic, Ole Miss is in essence an avenue to status in the state.” Agreeing, Wilkie explained, “Ole Miss functioned as a ... finishing school for the young women [and men] who would marry the elite and preside over their mansions.” It was, according to a New York Times reporter, a school “for the middle and upper classes, for posting ‘gentleman C’s,’ making ‘contacts’ and finding a suitable wife or husband.” The Mississippian’s regular announcements of engagements and marriages in a “To the Altar” column evidenced the importance of finding a mate at Ole Miss.21

A focus on personal appearance also suggested the significance of social affairs. The two Miss Americas were only the best-known examples of a student culture that celebrated female beauty. Ole Miss exalted physical attractiveness of women even before they enrolled in college by regularly hosting summer cheerleader camps for a thousand high school students and a camp for six hundred baton twirlers. In 1961 the university also sponsored a “Young and Beautiful Charm Camp” where more than two hundred “pretty” teenagers learned, among other skills, “how to use makeup effectively.” The stress on appearance did not stop with physical beauty but included clothing as well. Ole Miss coeds dressed up, but in ways too flashy for people accustomed to the more relaxed styles of northern colleges. For men the standard dress, which some outsiders considered several years behind national trends, included khaki pants, a white shirt, and scuffed loafers. More than other state colleges, and far more than many liberal arts colleges, the university exemplified the important social function performed by higher education. It served as a social and cultural institution even more than an academic one.22

Resembling their students, Ole Miss professors generally lacked a scholarly research drive, especially when compared t...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- The Price of DEFIANCE

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Introduction

- PART ONE Ole Miss and Race

- PART TWO James Meredith

- PART THREE A Fortress of Segregation Falls

- Notes

- Essay on Sources

- Acknowledgments

- Index