eBook - ePub

Island Queens and Mission Wives

How Gender and Empire Remade Hawai‘i’s Pacific World

- 184 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Island Queens and Mission Wives

How Gender and Empire Remade Hawai‘i’s Pacific World

About this book

In the late eighteenth century, Hawai'i’s ruling elite employed sophisticated methods for resisting foreign intrusion. By the mid-nineteenth century, however, American missionaries had gained a foothold in the islands. Jennifer Thigpen explains this important shift by focusing on two groups of women: missionary wives and high-ranking Hawaiian women. Examining the enduring and personal exchange between these groups, Thigpen argues that women’s relationships became vital to building and maintaining the diplomatic and political alliances that ultimately shaped the islands' political future. Male missionaries' early attempts to Christianize the Hawaiian people were based on racial and gender ideologies brought with them from the mainland, and they did not comprehend the authority of Hawaiian chiefly women in social, political, cultural, and religious matters. It was not until missionary wives and powerful Hawaiian women developed relationships shaped by Hawaiian values and traditions — which situated Americans as guests of their beneficent hosts — that missionaries successfully introduced Christian religious and cultural values.

Incisively written and meticulously researched, Thigpen’s book sheds new light on American and Hawaiian women’s relationships, illustrating how they ultimately provided a foundation for American power in the Pacific and hastened the colonization of the Hawaiian nation.

Incisively written and meticulously researched, Thigpen’s book sheds new light on American and Hawaiian women’s relationships, illustrating how they ultimately provided a foundation for American power in the Pacific and hastened the colonization of the Hawaiian nation.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Island Queens and Mission Wives by Jennifer Thigpen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1 Kamehameha’s Kingdom

In late November 1816, Hawai‘i’s King Kamehameha welcomed Russian naval officer Otto von Kotzebue to the islands. Kamehameha’s demeanor during the visit was by turns equally cordial and cautious. The king scrutinized Kotzebue and his crew from a distance. According to Kotzebue, Kamehameha sent several boats to meet the Rurick. He conducted interviews with members of the crew before greeting Kotzebue onshore. At their meeting, Kamehameha impressed his Russian guests with his “unreserved and friendly behaviour.” At the same time, the king evinced his wariness of foreign visitors by meeting the Russian vessel accompanied by “some of his most distinguished warriors.” Kotzebue observed that “a number of islanders, armed with muskets,” lined the shore. Kamehameha nevertheless acted the proper host, “conducting” his guests “to his straw palace.” He attempted to set them at ease by offering them European-style chairs—rather than the more customary mats—to sit upon during their visit. Through an interpreter, the king reassured his guests of his intention to offer them generous provisions “gratis,” just as he had previous visitors. Yet Kamehameha was also quick to demonstrate that he was no pushover, first by subtly invoking Captain James Cook’s ill-fated eighteenth-century voyage to the islands and then by recalling the recent but unsuccessful Russian attempt to conquer the islands. On the latter point, the king was direct: “This shall not happen as long as [Kamehameha] lives!”1

Throughout the visit, the king simultaneously attempted to remind his guests of their vulnerable foreign status and to cultivate positive relations with them. He trod this line carefully, expertly balancing displays of his political authority with gestures of gracious diplomacy. In retrospect, Kamehameha’s handling of the Russians emerges as emblematic of his leadership style, honed over the span of his reign and polished in his nearly constant interaction with foreigners from around the globe. Kamehameha, in fact, had ample opportunity to practice his political and diplomatic skills. By the time Kotzebue arrived in the islands in 1816, foreign ships—and their passengers—had become a more-or-less common sight in the islands, as visitors from Britain, France, and beyond made anchor at Hawai‘i.2 Though some came “merely” for purposes of trade or exploration, others arrived with more explicitly expansionist political and economic designs. All of them brought opportunities for more change. In response, Kamehameha developed a remarkably adaptive political style, which aimed not merely to endure foreign intrusion but also to secure Hawai‘i’s place within an emerging Pacific world.

This chapter describes some of the earliest encounters between the islands’ ali‘i—Kamehameha in particular—and their foreign guests during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and interprets them within the larger context both of aggressive Pacific exploration characteristic of the period and the internal political strife emanating from within the islands. The lasting negative effects of Western contact, well documented by historians, ethnologists, and anthropologists, can hardly be overestimated. Westerners introduced the idea of trade for money, a concept that spelled widespread destruction in the islands. The economic shift toward trade affected the islands’ economy in a direct way, but related changes imposed deeper alterations. In their quest to repay mounting debts to traders, ali‘i ordered maka‘āinana to cut down virtually all the sandalwood trees. This wrought havoc on the natural landscape, causing poverty and malnutrition among maka‘āinana.3 Moreover, Westerners brought new microbes and disease with them, which ultimately decimated the population of Hawai‘i. Some scholars, in fact, posit a precontact population of 1 million. Forty-five years later, the population of Hawai‘i dwindled to just under 135,000.4 These devastating realities powerfully shaped Hawaiian interactions with Westerners in the early part of the nineteenth century—particularly at the moment of American missionaries’ arrival in the islands.

Yet in the earliest years of contact, Hawai‘i’s ali‘i engaged in negotiations with Westerners from a position of power and authority. I argue that Hawaiians were not merely passive recipients of the changes initiated by foreign travelers, traders, and explorers; rather, King Kamehameha actively engaged in negotiations with foreigners with the intention of enhancing his own power while also increasing Hawai‘i’s political viability.5 My research demonstrates that the king insisted that foreign guests recognize and observe his political authority even as he shrewdly remained open to Western influence, adopting both Western dress and custom. The king proved especially adept at mobilizing these symbols of Western civilization when they seemed beneficial or provided the opportunity to facilitate trade.6 Yet Kamehameha also carefully retained and deployed important symbols of Hawaiian culture in his interactions with foreign guests.7 The king simultaneously and adroitly used both sets of symbols to communicate the legitimacy of his authority to an increasingly diverse, culturally foreign population with competing plans for the Hawaiian land and people.

Kamehameha’s political and diplomatic strategies are not only important for explaining and interpreting the kinds of dramatic transformations that occurred in the islands during his reign; they also provide a means by which to interpret ali‘i’s interactions with foreigners in the longer term. Though historians largely agree that Captain Cook’s arrival in the islands represents neither the starting point nor the “most significant event” in the narrative of Hawaiian history, the years between his 1778 visit and American missionaries’ arrival in 1820 were busy ones in the Pacific.8 Beginning in the 1780s, the islands in general and Honolulu in particular became a popular stopover for fur-trading ships destined for China. Due in part to the king’s savvy in dealing with foreigners, the islands became a “hub” of Pacific travel and trade. Some travelers, in fact, so enjoyed the physical and political environment that they took up permanent residence in the islands.9

By the time of Kamehameha’s death in 1819, Hawai‘i had taken on an increasingly global and cosmopolitan character. Indeed, throughout the nineteenth century, Hawai‘i’s ali‘i would be called upon to mobilize their skills as diplomats and political negotiators as the balance of power increasingly shifted to favor their Western visitors. Long before American missionaries arrived, in fact, ali‘i accrued a long history of engagement with culturally foreign populations, particularly those with competing plans for the islands and its peoples. This chapter helps to draw out a history of Hawaiian opposition to European and American aggression. That is, Kamehameha’s political vision not only informed his interactions with foreigners from the late eighteenth century until his death in 1819, but it also formed a lasting example of political diplomacy in the islands. Hawai‘i’s high-ranking women, in fact, most closely emulated his political style in their interactions with American missionaries in the 1820s and beyond, as I demonstrate in the chapters that follow.

Kamehameha’s interactions with Captain George Vancouver are particularly illustrative of the king’s political savvy. When Vancouver attempted to make anchor in Hawai‘i in January 1794, a small group of Hawaiians rowed out in canoes to meet his ship. Vancouver observed that a contingent of chiefs were assembled on the shore, “waiting in expectation” of his arrival. Kamehameha, flanked by some of the islands’ “principal chiefs,” greeted Vancouver with his “usual confidence and cheerful disposition.”10 This was Vancouver’s fourth visit to the islands; his first had been as a midshipman on Captain Cook’s crew thirteen years earlier in 1779.11 Much had changed in the intervening years. Both men, riding the rising tide of Pacific trade and travel, had experienced an increase in personal status.

Vancouver moved quickly up through the ranks of the Royal Navy. A mere midshipman under Cook in 1779, he became a lieutenant in 1780. He served a variety of commissions in this capacity until 1790, when he was made captain of the Discovery.12 He led an expedition with the joint aims of resolving property and trading-rights issues with the Spanish in the Nootka Sound and creating a detailed map of the northwest coast of North America for the specific purpose of confirming—or denying—the existence of a Northwest Passage. The two errands, though distinct, were nevertheless wedded by Britain’s desire to gain an economic foothold in the Pacific, a territory upon which Spain had cast a “blanket claim to sovereignty.”13 France, Russia, and the United States also sent ships into the Pacific not simply to explore the region but to exploit its vast and seemingly untapped natural resources.14

Vancouver’s explorations took him to locations throughout the Pacific—first to Australia and New Zealand, then through Tahiti and into British Columbia and Alaska and along the coast of California. He and his crew visited Hawai‘i during three separate winters beginning in 1792. Though Vancouver arrived in Hawai‘i informed by intelligence gained during his 1779 visit, the captain knew he would need to gain a greater sense of the islands’ current political and cultural landscape. Moreover, Vancouver sought to establish positive relations with the islands’ leaders.15 During these visits, Vancouver not only gained important insights into the islands but also became increasingly convinced of Hawai‘i’s strategic importance to Great Britain.

Like Vancouver, Kamehameha also increased his status in the late eighteenth century. While Kamehameha was high-ranking by birth, it was not inevitable that he would come to rule the island of Hawai‘i—nor would it have seemed likely that he would eventually become the first king of all the Hawaiian Islands.”16 Hawaiian men could improve their mana (power and prestige) in two ways: by mating with or marrying a high-ranking woman or through warfare.17 Kamehameha would make strategically valuable partnerships, marrying (among others) Keōpūolani and Ka‘ahumanu. Both were important bonds. Keōpūolani’s ancestry made her one of the highest-ranking ali‘i in the islands in her own right. Because of this, she was also a highly desirable marriage partner. This was particularly so for Kamehameha: producing offspring with Keōpūolani, as one scholar has noted, meant that “the whole lineage was uplifted.”18 Indeed, in this pairing, Kamehameha’s “lineage was further glorified.” It was Ka‘ahumanu, however, who purportedly became Kamehameha’s “favorite” wife. Not incidentally, she was also the daughter of Ke‘eaumoku, a man whose authority Kamehameha repeatedly—and ultimately successfully—strove to usurp. After Kamehameha’s death, Ka‘ahumanu became the king’s most politically powerful wife. During his life, however, Kamehameha relied on marriage as one means by which to enhance his authority over other chiefs—male ali‘i—in the islands. For their part, Kamehameha’s politically powerful wives seem to have absorbed and later adopted some of his most successful strategies of political diplomacy. They also made important adaptations of their own, as later chapters will demonstrate.

Kamehameha’s successful partnerships helped to solidify his status, but it was on the battlefield that he made his reputation, accrued loyalties, and, in the late eighteenth century, gained chiefly authority. For example, when Cook attempted to “secure”—kidnap—Kalani‘ōpu‘u, the mō‘ī (king) of Hawai‘i island, to redress a theft, Kamehameha took part in the resultant bloody battle in which Cook was ultimately killed.19 In the days following the melee, the “unfortunate” captain’s remains—consisting mainly of his bones—were returned to his crew. The ship’s surgeon, William Ellis, quickly observed that Cook’s hair had been cut. It was rumored that the captain’s hair was in Kamehameha’s possession.20 If Cook’s crew took this as a confirmation of Hawaiian “savagery,” Kalani‘ōpu‘u, who also happened to be Kamehameha’s uncle, likely understood it in somewhat different terms: Kamehameha retained Cook’s hair as a way to collect the foreigner’s mana, and, in the process, enhance his own.21 As the aging Kalani‘ōpu‘u prepared to step down in 1780, he appointed his son, Kīwala‘ō, as his heir and declared Kamehameha guardian of the war god Kuka‘ilimoku.22 The appointment was an honor befitting Kamehameha’s skill and stature.

Kīwala‘ō and Kamehameha’s relationship was a somewhat contentious one; their acrimony only intensified after Kalani‘ōpu‘u died in 1782. Kamehameha had defied Kīwala‘ō before; after Kalani‘ōpu‘u’s death, a handful of supporters encouraged Kamehameha to challenge Kīwala‘ō’s authority once again.23 At issue was the division of land that inevitably followed the death of a high chief. Feeling that they had been disadvantaged in the redistribution, Kamehameha and his supporters battled to gain control over the island of Hawai‘i. Kīwala‘ō was killed in an early skirmish, and Kamehameha claimed control of Kona, Kohala, and Hāmākua, which were on the western and northern parts of the island. Yet the victory was hardly decisive. The larger struggle lasted for the better part of a decade, as Kamehameha attempted repeatedly to dislodge his opponents from their districts on the southern and eastern sides of the island.24

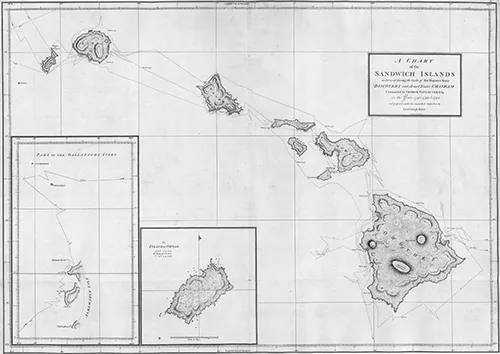

Vancouver’s Chart of the Sandwich Islands, ca. 1798. (Courtesy David Rumsey Map Collection, www.davidrumsey.com)

While Kamehameha’s rivals on the islands frequently eked out victories against him, Kamehameha nevertheless enjoyed a geographical advantage. European travelers doubtless remembered Kealakekua as the site of Cook’s demise; nevertheless, they expressed a preference for the bay, citing its tranquility and security. The bay, located squarely within Kamehameha’s territory, allowed him to capitalize on the opportunity to trade with Westerners who proved more than willing to supply Hawaiians with arms.25 Yet Kamehameha was not so easily won over to the Western way of war; he soon found that even “muskets and bayonets” were unreliable and sometimes ineffective. Hopeful of at last securing a victory, Kamehameha turned to more-traditional means of warfare. In 1791 he built a heiau (temple) at Pu‘ukoholā for his war god, Kuka‘ilimoku.26 The heiau, however, required a sacrifice. When Kamehameha completed the heiau’s construction, he summoned Keōua, his remaining adversary on the i...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Island Queens and Mission Wives

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- CHAPTER 1 Kamehameha’s Kingdom

- CHAPTER 2 Soldiers and Angels for God

- CHAPTER 3 When Worlds Collide

- CHAPTER 4 Gendered Diplomacy

- CHAPTER 5 Hawaiian Heroines

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index