![]()

1. Introduction

CARY CARSON

Colonial Williamsburg has earned many reputations since its founder, John D. Rockefeller Jr., began restoring the capital of eighteenth-century Virginia in 1927. Yet no part of its fame is so firmly fixed in popular imagination as its association with early American architecture. Millions of visitors to Williamsburg and millions more who have seen “Rockefeller’s restoration” only in magazine illustrations find it hard to forget the handsome public buildings where so much American history took place, the period taverns famous for their peanut soup and game pie, and most of all the attractive shops and houses that line the city streets. The houses especially feature in shelter magazines and home-decorating handbooks, season after season. Homebuilders have copied them far and wide (and inappropriately) from New England to Minnesota to California. Hardly a week goes by when Colonial Williamsburg’s staff of architectural historians doesn’t get calls, letters, or e-mails from people seeking advice about the right way to fix up their own old houses. Occasionally, in the aftermath of a Hurricane Hugo or a Katrina, the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation’s architectural specialists are flown to disaster areas to do for devastated buildings what the National Guard and the Red Cross do for the people whom the storms leave homeless. By now, the name “Colonial Williamsburg” is synonymous with architectural expertise.

The authors of this book are those selfsame experts. Most of us are or have been employees of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation for many years; a few of us are independent researchers with whom the rest of us frequently collaborate. We all gladly share what we know about early buildings, but, until now, usually with one person or one group at a time. By writing this book, we hope to reach a much-wider audience of students, teachers, preservationists, and architectural experts in other parts of the country, old house buffs, and history lovers generally. Here at last, assembled between two covers, is the knowledge we inherited from our predecessors, plus everything else our generation has brought to the task of renewing Colonial Williamsburg’s worldwide reputation in this field.

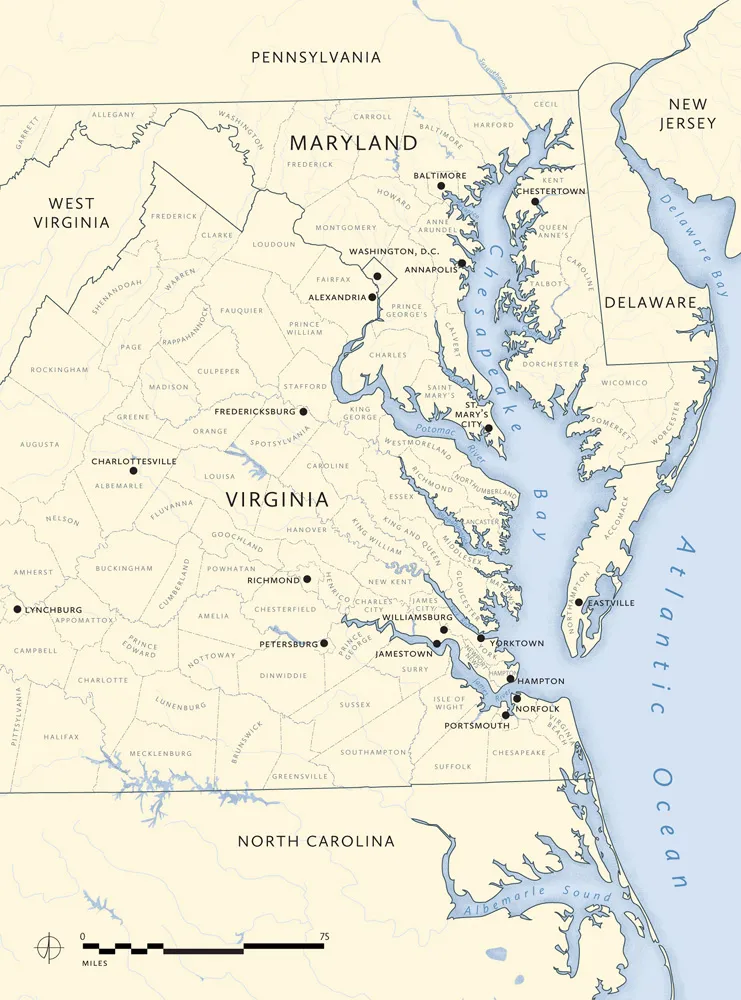

Aerial view of Jamestown Island, © Cameron Davidson.

The fact that our interdisciplinary team of historians, archaeologists, curators, and conservators works for a history museum is not without consequence for the study of domestic architecture. In an age when all buildings were designed locally and built mostly with materials prepared on site, architecture varied significantly from region to region. Colonial Williamsburg takes regional history to heart. It has to. Every outdoor history museum occupies a given time and place in the past. It therefore stands to reason that field research undertaken by the foundation has always been narrow and deep. The narrow part focuses on those tablelands across Virginia and Maryland that water the Chesapeake Bay (Fig. 1.1). The Bay and its tributaries were the locus of a seventeenth- and eighteenth-century agricultural economy organized principally around the production of tobacco for export overseas and eventually food crops for sale to hungry cities nearer by. As historian Lorena Walsh explains in her scene-setting chapter, the tobacco economy forced planter-settlers who migrated to these shores to make different choices than those made by colonists elsewhere. The one choice that impressed its mark on architecture almost immediately was the advantage to be gained by cultivating the crop with a labor force of indentured English servants and enslaved Africans. The tobacco economy and the slave society it fostered effectively drew boundaries around the watershed that the authors of this book call the Chesapeake region. Likewise, tobacco and slave labor gave the Chesapeake house a special function and appearance that distinguished it from farmhouses and town houses beyond the region, to the north in Pennsylvania and southward along the Albemarle Sound into the Carolinas, and even in the western counties of Maryland and Virginia, where the Piedmont economy and the farm labor it employed made different demands that required different kinds of buildings. This book then is the product of a museum research program that has explored one region, its buildings and its records, relentlessly, for almost ninety years. Chesapeake architecture is now the most exhaustively studied seventeenth- and eighteenth-century building tradition in North America. Not even New England has been so thoroughly pored over and analyzed.

Working for a history museum has influenced the scholarship presented in these pages in another respect. Whatever renown it enjoys for its architectural collection and the antique furnishings on view in its exhibition buildings, Colonial Williamsburg remains a history museum first and foremost. That means that the restored buildings and decorative arts have been assembled ultimately to set the stage for a telling of the American story that gives starring roles to the participants, not to the settings or the props. The men and women who lived in Williamsburg or came to town on business or pleasure occupy center stage in the museum’s educational mission. It therefore behooves us, the foundation’s curators and architectural historians, to learn how buildings and furnishings actually worked for the people who acquired and used them.

That intrinsic connection between dwellings and dwellers guides our research and now provides the underlying rationale for this book. The buildings we study belonged to an age before factory-made materials and mechanized transportation had begun chipping away at the localness of bespoke architecture. Surviving indigenous buildings retain their value as prime sources of historical evidence about people who lived long before the modern world homogenized everyday life. Those people are our ultimate quarry in this study — men and women of European and African descent, rich and poor, free and enslaved, native born and newcomers — in short, all who resided in the two neighboring colonies (and eventually the independent states) of Virginia and Maryland. Their story — how the houses they built gave architectural shape to their relations with everybody who shared their domestic space — is that part of our book that answers to the title, The Chesapeake House.

The most conspicuous figures in this landscape were the great planters, who, though relatively few in number, dominated the scene that travelers to the region remarked on at the time (Fig. 1.2). They figure disproportionately in this and all other studies of Chesapeake architecture because their buildings enjoyed a better chance of survival. But, could you yourself be a time-traveler back 200 years ago, you would encounter other landscapes less familiar now but well known then to a cast of characters that will appear frequently throughout this book. In the neighborhoods around every great estate, you would, for instance, find a countryside that swarmed with ordinary people who seldom or never set foot on a gentleman’s property and only occasionally crossed paths with the local grandees at church, the courthouse, the muster field, or by chance along the highway (Fig. 1.3). The commonplace world of small freeholders, tenant farmers, indentured servants, and most slaves assumed a much-reduced scale — smaller farms, modest wooden farmhouses, fewer specialized farm buildings, and here and there a solitary quarter that lodged the two, three, four, or five bondsmen that were all the chattel laborers that most slave owners could afford. Not surprisingly, few of these smaller farmhouses remain standing today, and eighteenth-century slave cabins and agricultural buildings are fewer still. What we know about such ephemeral structures comes instead from archaeological excavations, written records, and, occasionally, drawings.

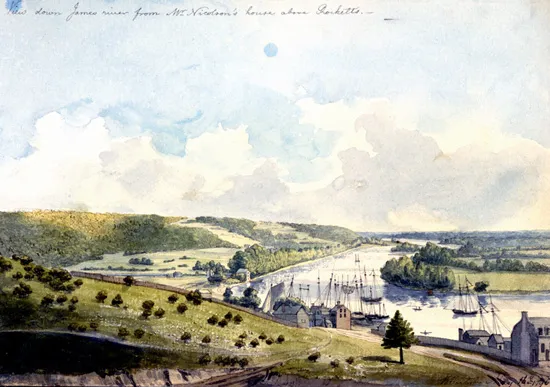

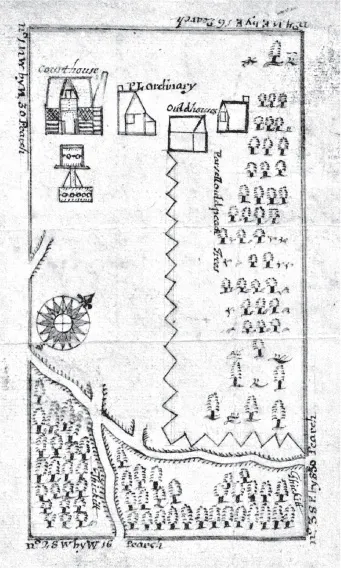

Were you to take an even-wider-angle view across the Chesapeake landscape, you would glimpse yet another Tidewater setting in the far distance — the region’s urban settlements, such as they were. An increasingly complex Chesapeake economy gave rise to a few genuine towns and cities by the middle of the eighteenth century — for example, Norfolk, Williamsburg, Yorktown, and Petersburg in Virginia and Annapolis, Oxford, and Chestertown in Maryland (Figs. 1.4, 1.5). The time-traveler’s eye would also pick up a sprinkling of lesser gathering places — wharves and warehouses with adjacent stores and taverns located at landings along some of the larger creeks and rivers (Fig. 1.6). Inland, yet more stores and taverns clustered around courthouses and jails at county seats (Fig. 1.7). Such settlements notwithstanding, the Chesapeake region remained overwhelmingly rural before the Revolution and only marginally less so afterward.

Fig. 1.1. The Chesapeake region.

Fig. 1.2. “Horsdumonde, the house of Colonel Skipwith, Cumberland County, Virginia,” 1796. Drawing by Benjamin Henry Latrobe. (Courtesy of the Maryland Historical Society, 1960.108.1.2.4)

These three typical landscapes set the scenes that play out in the following pages. They are animated landscapes everywhere you look. The scenery is crowded with actors. Some are the “undertakers,” craftsmen, tradespeople, and laborers who planned, built, finished, and furnished the Chesapeake house. Storekeepers, merchants, ship captains, and London agents managed the supply lines that equipped the builders with the tools and materials that could not be manufactured economically in the colonies. Still other players are the householders themselves, whose lifestyles further shaped and reshaped their dwellings from the inside, out according to the uses they made of their homes and the ways they altered those uses over time. In effect, the cover of this book works like the front door to any one of the hundreds of houses described herein. Open it and discover not empty rooms, but furnished, functioning, living interiors. Chapter 2, “Architecture as Social History,” is a primer to the research strategy that led to the choice of buildings we have studied and the methods we have employed to understand what dwellings can tell us about people’s house habits, which back then were so different from our own.

Explaining those methods and sharing our findings are the principal purposes of this volume. They are the promise implied by the book’s subtitle, a pledge to readers to describe the practice of architectural investigation by Colonial Williamsburg. A chapter on modern field-working techniques explains the tools and methods architectural historians use today to measure, photograph, and otherwise record structures in the field. Some were pioneered by our predecessors and have remained useful ever since; others our own generation has invented or improved upon. All demonstrate that field-recording methods depend first, foremost, and fundamentally on the questions that researchers believe are the most important ones to ask about houses and their inhabitants. Questions lead to hypotheses, hypotheses to tests, tests to a search for pertinent evidence, and the discovery of evidence to methods of recording and storing information that can be shared reliably with other people in books like this one. Most readers will never have an opportunity to visit the buildings in question and evaluate the evidence themselves. Field-recording techniques therefore quarry the building blocks needed for our own scholarship and for its future reinterpretation by those who follow us.

Fig. 1.3. Countryside around Williamsburg, Virginia, 1781. Detail of map by Nicholas Desandrouin. (Rochambeau Collection, Library of Congress)

Fig. 1.4. “Sketch of York town, from the beach, looking to the West,” 1798. Drawing by Benjamin Henry Latrobe. (Courtesy of the Maryland Historical Society, 1960.108.1.4.9)

Fig. 1.5. “Old Annapolis, Francis Street,” 1876. Painting by Francis Mayer. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1916 [16.112], Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Fig. 1.6. “View down James river from Mr. Nicolson’s house above Rocketts [Landing],” 1796. Drawing by Benjamin Henry Latrobe. (Courtesy of the Maryland Historical Society, 1960.108.1.39)

Fig. 1.7. Plat of Charles County, Maryland, courthouse grounds, 1697. (Maryland State Archives)

The architectural evidence we and other field-working historians have collected since 1980 rivals the treasure trove assembled by the restoration architects who worked for Rockefeller three-quarters of a century ago. Their work and ours, added together, form the substance of the book. The following sixteen chapters are organized into four parts, starting with the opening essays on our goals and methods followed by a concise economic and social history of the region. Part 2 treats the design and use of buildings front and center. It gives architectural dimension to historical problems that figure prominently in broader academic and professional literatures. Here, though, our prime audience is expected to be those general readers who often share the authors’ specialized interests but usually lack their formal training. Three chapters trace the development of regional house forms and shifts in domestic lifestyles, from the initial settlements at Jamestown (Virginia) and St. Mary’s City (Maryland) through the 1830s. Two additional chapters describe housing for servants and enslaved Africans and their typical plantation workplaces, including farm buildings. These essays engage ongoing historical debates about the region’s agricultural diversification and a labor system increasingly based on slavery. They raise questions about the transfer of ideas and expectations from the Old World and the conditions that immigrants encountered in the colonies that encouraged innovation and rewarded risk-taking. Some essays explore the impact of class and race on the design of buildings and their layout on the landscape. Others tell of contests between polite and popular culture and the diffusion of store-bought consumer goods and the spread of etiquette-book manners, even to remote rural backwaters. Still other essays chart the growth of modern pleasure towns and the gradual adoption of urban lifestyles by country folk. All are familiar topics to American historians. Here they acquire the three-dimensional settings that ground these issues in real-world built environments. A conversion takes place in the process. Subjects well understood by economic, social, cultural, and urban historians are reformulated to contribute to a newer-fangled history of American material life, a 400-year-old story that takes account of people’s increasingly complex dependence on man-made objects to communicate their relationships with one another and to steer their daily progress through the social worlds they inhabited.

A book about architecture should also be a “brass tacks” book about the building process. Ours is that too, starting with Carl Lounsbury’s chapter, “The Design Process.” He and later authors find that building practices took shape in the colonies in response to pressures and conditions that challenged people’s conventional notions about what a house should be. How Virginians and Marylanders then organized themselves to meet their new needs also reflected circumstances that often were peculiar to the region. The strategies they employed were themselves remembered-from-home, on one hand, and on another were a response to the new realities of life in Virginia and Maryland. How, for example, did clients and builders from different regions in the British Isles reach a meeting of minds on an acceptable design for structures to accommodate their start-over lives in North America? How were building trades in the colonies organized to accomplish construction work? In the case of plantation housing for slaves, what domestic arrangements were white masters content to leave to the very different cultural preferences of their African bondsmen? Both the chapter on building design and Edward Chappell’s on slave quarters and workplaces raise these questions about the production of material culture by introducing readers to the men and women who formally planned and built Chesapeake dwellings and others who informally adjusted those accommodations to meet their own preferences and everyday need...