![]()

Part I

The Republican Era, 1867–1912

![]()

Chapter One

No South to Us

African American Federal Employees in Republican Washington

As long as I have been colored I have heard of Washington Society.

—Langston Hughes, Opportunity, August 1927

Washington, D.C., was the nation’s most important city for African Americans at the turn of the twentieth century. Black Washingtonians’ cultural and educational institutions, political connections, and prospects for stable employment stood out against the penury, terror, and segregation that plagued black lives elsewhere in the United States. Four decades of decent employment in federal offices had made Washington a city of opportunity and relative freedom for black men and women, a place where respectability and status could be earned by work in the nation’s service. The salaries paid to black federal clerks fueled a growing black middle class, and its power and prestige limited racial discrimination in the city. Life in the District was hardly free of racism or struggle. But for ambitious African Americans, the social as well as economic value of federal positions was incalculable.

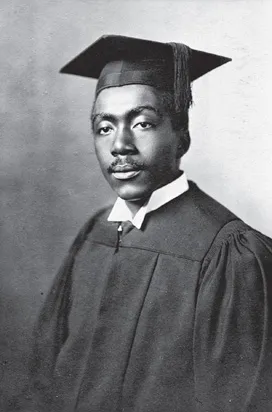

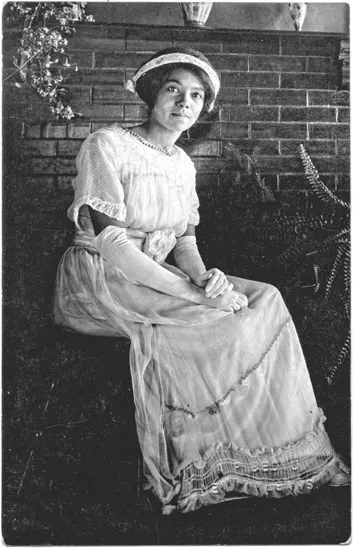

In 1911, twenty-seven-year-old Swan Marshall Kendrick traveled from the Mississippi Delta to Washington because a clerical job in the War Department promised decent and reliable pay. He was emblematic of the capital’s striving black middle class. A Fisk University graduate, Kendrick was soon promoted and placed in charge of managing the Small Arms and Equipment Division’s complex filing system, corresponding with munitions and manufacturing firms, and preparing reports for Congress.1 On warm weekend afternoons, he joined the young people on the Howard University hill talking about their futures, “the work we want to do, of the lives we want to live, of the possibilities of achieving some of our desires.”2 His work hours—9 A.M. to 4:30 P.M. on weekdays; 9 A.M. to 1 P.M. on Saturdays—left him time to stroll the capital’s streets, read at the congressional library, and dream up life goals. Most days ended with some satisfaction and “the usual ‘pie and glass of milk.’”3 Soon, he began describing his life to his beloved Ruby Moyse back home in Mississippi: the city’s “eternal rumble of the cars, ringing of bells,” his plans to travel the world “in first-class style,” his hopes of giving his wife and children “every opportunity,” and the inspiration he took from reading W. E. B. Du Bois to “help along, even in a small way, a cause [of civil rights] which is the greatest since the anti-slavery crusade of [William Lloyd] Garrison and [Wendell] Phillips.”4 It was not a bad life, if a bit humdrum: “Easy work; short hours; good pay; lifetime job; What more could a sane man want?”5 One thing was “sure as fate,” he declared in February 1913, a month before Woodrow Wilson moved into the White House. “I’m bound to win.”6 Washington was not Mississippi.

When Kendrick arrived in Washington, the capital had only recently come into its own as a city. The mud-filled nineteenth-century streets mocked by Charles Dickens and Henry Adams had given way to asphalt boulevards and elegant parks. In the years after the Civil War, a flood of new residents, black and white, had come for government employment and to take part in the ascendant American state. The prosecution of a war and the management of a huge army had swollen the federal government and employed new wageworkers, especially women. In the early 1860s, the city’s population doubled and never shrank back to its prewar size. The provincial and largely undistinguished District was poised to become a metropolitan capital.7 In the following decade, Washington officials and civil servants began working and spending money—enormous amounts of money—to modernize Washington. Alexander “Boss” Shepherd, through his post as director of public works and later as governor, disbursed $20 million, considerably over his $6 million budget, to lay pavement, sewer lines, and gas pipes; to erect streetlights; and to plant trees.8

By the 1880s, charming social clubs, dazzling department stores, and grand palace theaters were beginning to replace the smokers and saloons that had marked the city as foul and profane to visitors in the past. Elegant late-Victorian homes and apartment buildings proceeded in impressive rows across the western quadrants. The city proudly promoted its scenic beauty, mild winters, and educated society.9 It had become a place where dignified women could embody the city’s essence. “Washington,” rhapsodized journalist Alfred Maurice Low in 1900, “is like a woman whose very presence radiates happiness, whose beauty and grace and charm make the world better for her being.” Unlike other American cities, Washington had not been disfigured by factories, leaving it clean and cordial. In that way, concluded Low, “Washington is not America.”10 And yet it was also the central worksite of the American state, a city of civil servants doing the nation’s business.

The work federal employees did varied greatly, from postal employees carrying letters to chemists conducting experiments at the Department of Agriculture to laborers at the Navy Yard unloading steel. The term “clerk,” noted civil service reformer El Bie Foltz in 1909, was actually a capacious category that included “copyists, stenographers, typewriters, transcribers, indexers, cataloguers, assistant librarians, certain kinds of attendants, translators, statisticians, section chiefs, abstracters, assistant chiefs of division, and a large number of miscellaneous employe[e]s whose duties are of a clerical nature.”11 In other words, the clerks administered modern government by doing its paperwork.12 “A cynic must not think that because Washington makes very little smoke, it does not hold an important place in the national economy,” a local journalist reminded the nation in 1908.13 The Washington Board of Trade imagined the city sitting atop the entire southern economy, serving as a gateway to the North.

As the progressive state began to expand in power and size, it increasingly connected Washington to the nation. National government, all agreed, was Washington. By 1900, nearly a quarter of all jobs in the capital were with the federal government.14 “It is our daily bread; it is the thread which runs through the woof and warp of our lives,” sang Low. The result, he said, made the capital “the paradise of the poor man with brains.”15 The steady paychecks of the clerks, generally between $1,000 and $1,600 a year, began to support new real estate and retail markets. These roughly 10,000 men and women were the city’s “backbone,” declared former District commissioner Henry L. West in 1911. “Whatever is done for the government clerks,” he said, “is done for the whole city.”16

Swan Kendrick, circa 1909, and Ruby Moyse, circa 1915. Though he was invited by the family to court her older sister, Swan Kendrick met and fell in love with Ruby Moyse in Greenville, Mississippi, around 1911. When government work took him to Washington, Kendrick romanced Moyse by letter for nearly five years before she agreed to marry and join him in the capital. Often critical of what Moyse called “High Colored Society,” both had relatively privileged childhoods in the Mississippi Delta and received the best education available to African Americans at the turn of the twentieth century. As their fine clothes and confident poses attest, these young people, born in the mid-1880s, faced the future with prospects and ambition. (Kendrick-Brooks Family Papers, Library of Congress)

African Americans lived in every quadrant of the city and worked in every department of the government. They made up about one-third of the population and over 10 percent of federal employees at all levels.17 More than 350 black men and women held clerical positions, meaning that African Americans, too, were a part of the city’s elite backbone. While black Washington contained exceptional contrasts, with its famous “colored aristocrats” standing out against a backdrop of laboring and underemployed masses, the experiences of its middle strivers, the white-collar clerks, embodied the aspirations of the capital city in the new century. Black government employees like Swan Kendrick earned more-than-decent salaries of $1,200 a year. They were experiencing social mobility.18

The nation’s African American press carried news of black Washington’s china and crystal banquets across the country every week.19 While never dominant in the capital at large, this black bourgeoisie—with its connections to government and politics—was more prominent and more remarked upon by black and white Americans alike than any other group of African Americans anywhere. “The eyes of the entire country are upon the 100,000 Negroes in the District of Columbia,” announced Booker T. Washington in 1909, with his typical combination of aggrandizement and didacticism. “The nation looks to the happily environed, intelligent, well-paid and dignified colored people of the capital for inspiration, example, and instruction.”20 New York, Baltimore, and New Orleans contained prominent black elites, and Norfolk had government laborers in its navy yard, yet in no other American city did black people collaborate with the state as productively as in Washington.21 That the District of Columbia was administered by the federal government made all the difference, because it meant that black Washington’s civic virtues lasted long after white supremacists crushed similar societies elsewhere.

The Black Capital

Thousands of African Americans were enjoying the newly vibrant capital at the turn of the twentieth century. Washington’s black population of 86,000 not only outnumbered that of any other American city in absolute size but also far surpassed most major cities as a proportion of the total population.22 Though black city boosters correctly decried the District’s loss of the franchise in 1878 as an effort to undermine black political participation, they continued to proclaim Washington a place of real opportunity for African Americans.23 Black men and women might read comfortably in the city’s public library, sit in integrated audiences at the Belasco Theatre, or even share a drink with white Washingtonians at some saloons.24 Black and white city papers announced the doings of the black government workers, politicians, and businessmen who sat in Martin’s Café, a black-run restaurant, to participate in the meetings of the city’s famous Mu-So-Lit Club. They also reported on the myriad scholarly papers and manifestos read at the Bethel Literary and Historical Society, the intellectual home of Du Bois’s “Talented Tenth.”25 Black Washingtonians built businesses and established innumerable orders of Freemasons, Odd Fellows, Elks, Knights of Pythias, Woodmen of America, Mosaic Templars, and True Reformers. Washington was also the organizing site of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, created in 1895 for the moral and social uplift of “the race.”26 The grand pulpits of the Metropolitan AME Church, Fifteenth Street Presbyterian Church, and Nineteenth Street Baptist Church not only spoke for the souls of black Washington but also were key organizing stations for political, civic, and philanthropic movements. But these were only the most famous: less prominent sanctuaries included Shiloh Baptist, Plymouth Congregational, and John Wesley AME Zion.27

Washington was home to the nation’s most elite black Americans, including former Mississippi senator Blanche K. Bruce, North Carolina author Anna Julia Cooper, the stylish and outspoken social reformer Mary Church Terrell, and former Louisiana governor P. B. S. Pinchback.28 Accomplished men and women announced their power and affluence by promenading down Connecticut Avenue on bright Sunday afternoons, building hotels and restaurants, paying for expensive church pews, and hosting endless receptions.29

For the city’s children, the black elite erected good schools that exemplified modern education. Congress had created the ...