- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Sister Thorn and Catholic Mysticism in Modern America

About this book

One day in 1917, while cooking dinner at home in Manhattan, Margaret Reilly (1884–1937) felt a sharp pain over her heart and claimed to see a crucifix emerging in blood on her skin. Four years later, Reilly entered the convent of the Sisters of the Good Shepherd in Peekskill, New York, where, known as Sister Mary of the Crown of Thorns, she spent most of her life gravely ill and possibly exhibiting Christ’s wounds. In this portrait of Sister Thorn, Paula M. Kane scrutinizes the responses to this American stigmatic’s experiences and illustrates the surprising presence of mystical phenomena in twentieth-century American Catholicism.

Drawing on accounts by clerical authorities, ordinary Catholics, doctors, and journalists — as well as on medicine, anthropology, and gender studies — Kane explores American Catholic mysticism, setting it in the context of life after World War I and showing the war’s impact on American Christianity. Sister Thorn’s life, she reveals, marks the beginning of a transition among Catholics from a devotional, Old World piety to a newly confident role in American society.

Drawing on accounts by clerical authorities, ordinary Catholics, doctors, and journalists — as well as on medicine, anthropology, and gender studies — Kane explores American Catholic mysticism, setting it in the context of life after World War I and showing the war’s impact on American Christianity. Sister Thorn’s life, she reveals, marks the beginning of a transition among Catholics from a devotional, Old World piety to a newly confident role in American society.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sister Thorn and Catholic Mysticism in Modern America by Paula M. Kane in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Teologia e religione & Storia nordamericana. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Now You Are My Thorn, but Soon You Shall Be My Lily of Delight

The Transformation of Margaret Reilly

A soul is of more value than a world.

—Rose-Virginie Pelletier (Saint Euphrasia), founder of the Sisters of the Good Shepherd

—Rose-Virginie Pelletier (Saint Euphrasia), founder of the Sisters of the Good Shepherd

Pain and grief, oh, do not spare me,

Let my soul and body smart,

Happy will I be to suffer

To console Thy anguished Heart.

—Stanza of “To the Lily of His Heart,” a poem written by Sister Mary Carmelita Quinn and sent to Sister Mary Crown of Thorns in January 1924

Let my soul and body smart,

Happy will I be to suffer

To console Thy anguished Heart.

—Stanza of “To the Lily of His Heart,” a poem written by Sister Mary Carmelita Quinn and sent to Sister Mary Crown of Thorns in January 1924

Margaret Reilly received a nudge toward sainthood on an ordinary day in 1917 while cooking dinner. Although the kitchen seems an unlikely place for a mystical encounter, Margaret, while stooping over the oven to prepare a fish supper with her mother, felt a sharp pain over her heart and saw a three-dimensional crucifix emerging in blood. Her mother quickly put her to bed and immediately telephoned their pastor.1 This event was not Margaret’s first divine communication. Four years earlier, in November 1913, a two-inch-long red cross had appeared on her breast. On that day, she recalled, “It pleased our dear Lord to send me a very severe illness for which He prepared me in a most extraordinary way. In my illness, I beheld our dear L. nailed to the Cross and covered with Wounds…. ‘Thorn,’ He called me; ‘upon thy breast I place a Cross.’ My eyes raised above. He smiled and spoke: ‘Take thou this Cross because ‘tis Thorn I love.’ Then a sharp pain … when suddenly my eyes closed to all around me. My very soul became entirely rapt and absorbed in the contemplation of the Most Holy Trinity.”2

Margaret’s divine rapture soon inspired others to offer their own interpretations of the events of 1917. One asserted that the arrival of the crucifix on Margaret’s skin was the Lord’s resolution of a dispute between Margaret and her confessor.3 Apparently, Margaret had taken up the penitential practice of wearing a hair shirt, usually on Friday afternoons from twelve until three o’clock. After about eight months, Jesus told her to advise her confessor that she should stop wearing the shirt. The priest thought that Margaret should continue the practice, but he also came to understand that God would send a sign to both of them in the form of a cross on her chest.4

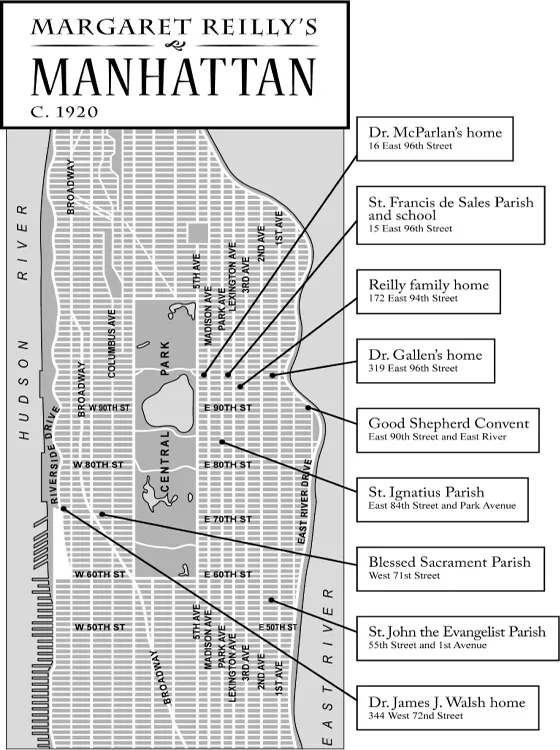

Key sites in Margaret Reilly’s Manhattan. (Digital drawing, Alec Sarkas, University of Pittsburgh; property of author)

Whatever its origin, the crucifix over Margaret Reilly’s heart in 1917 remained visible until December 8. In a friend’s recollection, the mark resembled a “raised, sunburned area,” pale pink, and not more than two inches long.5 The three-dimensional corpus even changed color. According to one chronicler, “Sometimes it was red, sometimes purple, sometimes livid. Jesus revealed to Little Thorn the meaning of the changing of colors; it meant sufferings of His Church in various ways.”6

Margaret’s crucifix reappeared in a different venue four years later while she was making a spiritual retreat at Mount St. Florence, the convent of the Good Shepherd sisters in Peekskill, New York. There, in October 1921, the image again appeared on Margaret’s chest and then transferred itself miraculously to the wall of her temporary residence. It was observed by Dr. Thomas McParlan, the physician who had accompanied Margaret to the convent, as well as by Mother Raymond Cahill, the convent superior, and several of the Good Shepherd sisters. Mother Cahill surrounded the transferred image with a picture frame, containing and protecting the vivid red stain on the stark white wall.

This chapter describes the unusual mystical events of Margaret Reilly’s life and seeks to understand them in the context of Irish American history in New York and of American Catholicism of the early twentieth century. Most of the chapter is necessarily taken up with establishing a sequence of events and biographical details from archival sources. Later chapters will revisit significant episodes and continue through the end of her life. Using the accounts of Margaret’s experiences compiled by several contemporaries, this chapter sketches the events of her stigmatization, then returns to follow Margaret’s family life from childhood to young adulthood, her convent appearance in 1921, her experiences in the convent until she made her final vows in 1928, and her encounters with priests and sisters who interpreted her divine and diabolical experiences.

When the crucifix returned to Margaret’s chest in 1921 after the preludes of 1913 and 1917, she had just arrived at Mount St. Florence, located in an idyllic and secluded setting on the heights of the Hudson River, to perform a Catholic activity known as a spiritual retreat. On a late September afternoon, Margaret had taken the train north from Manhattan to Peekskill to undertake this silent exercise. Accompanied on the journey by McParlan, her family doctor—who had recommended the retreat, and this convent in particular, because of his friendship with the superior—Margaret had been granted a special favor. Ordinarily, a convent that housed any cloistered nuns did not accept outsiders, especially as overnight guests. McParlan, however, had close ties to the congregation and to the Catholic hierarchy, serving as the personal physician to the prior and present archbishops of New York, John Farley (1902–18) and Patrick Hayes (1919–38). With McParlan’s approval, Margaret was installed in a makeshift room inside the parlor or in a cell inside the cloister.

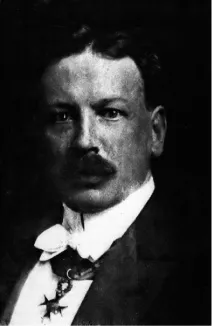

Dr. Thomas F. McParlan (1870–1928), the archbishop’s private physician and Sister Thorn’s unwavering advocate. (Photo of prayer card by author)

Margaret’s first three days at Peekskill were quiet and uneventful. Then, on the fourth morning, Margaret took a stroll to view a statue of the Sacred Heart of Jesus on the convent grounds. As she returned to her room to lie down, she had a vision of Jesus standing at the foot of the bed. He said, “I give you my cross upon your breast, because I love you much: and you are to suffer for My very own.”7 Jesus explained that “my very own” referred to priests and nuns. The same image from her chest was miraculously duplicated on the wall of her room at Mount St. Florence. About three inches in length, it was seen there by the Mother Raymond, who was further surprised to find that Margaret’s left side and feet were now bleeding. Mother Raymond reported to one of Margaret’s cousins, who was also a nun: “She has shown me her beautiful Cross and you may feel certain that she was most welcome.” Even before Margaret’s arrival at Peekskill, Mother Raymond claimed to have witnessed (although she does not specify where) the perfectly formed cross and corpus with its feet resting on Margaret’s heart, “at time diffused with blood.”8 For the next thirty-three days—each day, as the superior believed, symbolizing a year of Jesus’s life—Margaret remained bedridden at the convent in acute pain and bleeding profusely from four wound sites in her hands and feet. Jesus told Margaret that the foot wounds were the beginning of her complete stigmatization.9 Puncture wounds appeared around her forehead as well, as though from a wreath of thorns. In a vision, Jesus told her that she would now be named “Thorn.”10 “Now you are my Thorn,” he proclaimed, “but soon you shall be my Lily of Delight.”11

In a breach of convent procedure, Mother Raymond herself cared for Margaret, changing linens and bandages as they were saturated with blood. Sister Mary of St. Luthgarde, the infirmarian, assisted Mother Raymond.12 The superior’s activity recalled her novice days at the Brooklyn Good Shepherd convent, where her tasks involved doing the hospital laundry, washing bandages, and even disposing of the remains of body parts left on the linens and bandages from surgical procedures. Mother Raymond’s niece recalled that her aunt had intensely disliked this chore.

Mother Raymond was known as “a magnetic personality” with “wide experience” who was trusted by the many persons who came seeking her advice.13 Born Bridget Cahill in Worcester, Massachusetts, she was the eldest daughter of parents born in Ireland. Her father was a skilled shoe designer who worked in the region’s several small shoe factories. As a child, Bridget contracted undulant fever, a chronic bacterial infection often caused by unpasteurized cow milk or contact with other infected livestock. The family moved for a few years to the nearby town of Spencer, Massachusetts, as recommended by the doctor. Bridget and her two sisters then attended all twelve years of school at Ascension Academy in Worcester, directed by the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur, while the Cahill sons attended St. John’s School. At the time of her first Communion at age fourteen, Bridget beheld a vision of the Christ child that spanned several nights. It ended when her father entered the vision. Her pastor-confessor told her that she should be at peace and that the vision would not return again. This story, passed down in Cahill family lore, perhaps explains Mother Raymond’s unqualified acceptance of Sister Thorn’s mystical experiences.14 Bridget was a clever and creative young woman who even made money publishing poems under the names of known authors, a common practice.15 After high school, Bridget asked the local department store to pack her trousseau and ship it to the Brooklyn Good Shepherd convent. Her father, a lapsed Catholic for most of his life, disavowed her and never visited her in the convent after her entrance in 1900. Some ten years later, he resumed Mass attendance in Massachusetts, but it is unclear if he ever reconciled with his daughter.

As a young superior, Cahill was perplexed about how to deal with the disturbing circumstance of having a stigmatization within her religious community. No doubt she prayed for guidance and help from her chosen namesake, Saint Raymond Nonnatus, the patron saint of the falsely accused, as her own community began to challenge her support for Margaret. She began to keep a detailed daily journal of the appearance of Margaret’s wounds.16 Not until thirteen years later did Mother Raymond admit to any uncertainty about Margaret Reilly; a year after that, during a private chat with Mother Raymond at Mount St. Florence in 1935, the newly arrived Sister Martha Marie Crowley expressed doubts about reports of the “strange and threatening manifestations” that were occurring in Margaret’s room. “I was not ready to believe in the mystical or occult,” Crowley recalled. During that conversation, Mother Raymond also confided in Crowley about “her own doubts in her early associations with ‘Little Sister’ (as she was known in the community), her anxiety and her prayers to know the Will of God.”17

Following Jesus’s directive, Mother Raymond moved Margaret into the anteroom adjoining her own bedroom. This fateful decision meant that when Margaret later applied to enter the Good Shepherd order, she had avoided the deprivation of the regular postulants, who began their communal life in the small cells on the ground floor in the least heated part of the convent building. Within two months of her arrival at Peekskill, the bleeding of Margaret’s stigmata had intensified in gruesome ways, and she continued to feel unbearable pain at the wound sites from Wednesday through Friday each week. On November 11, her face was marked as though by whips. Margaret said “she could feel the separate lashes as they were given on her face, also when they were given on her whole body. These lashes were sometimes inflicted by our Lord Himself, or by St. Michael or by her Guardian Angel. Margaret could even see this instrument: the discipline contained 48 strips of fine steel with thorn-like projections. There was also a piece of lead 2 1/2 inches long attached to the center ring.”18 Mother Raymond reported that among Margaret’s wounds, the scourge marks were “more painful than the wounds of the hands and feet and side. The pain in the chest is as if an army of people were kneeling on the chest.”19

The cross impressed on the skin over Margaret’s heart that began this chain of events disappeared entirely from her body around December 15, 1921, but her mystical communications did not end.20 Throughout the following years, Margaret continued to receive spiritual gifts often associated with stigmatics: a crown of thorns around her head and a mystical marriage to Christ, followed by the replacement of her visible wounds by invisible stigmata. She reported a burning heat in her third finger of the left hand where Jesus placed a wedding ring, which was perceptible only to her.21

After three months at Mount St. Florence, Margaret left the convent at least once, although this trip is not mentioned in the convent’s records. In December 1921 she visited her cousin Sister Rita (Mary Connolly) at the Ursuline convent of Brown County, Ohio, about forty-eight miles from Cincinnati.22 Since Margaret had lost both parents in the preceding three years, her Connolly cousins were now her closest relatives. Her bleeding woun...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Sister Thorn and Catholic Mysticism in Modern America

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1 Now You Are My Thorn, but Soon You Shall Be My Lily of Delight

- 2 The Monastery Is a Hospital of Spiritual Sick

- 3 Mad about Bleeding Nuns

- 4 We Are Skeptics Together about a Great Many Things

- 5 Cor Jesu Regnabit

- 6 It Is Beautiful to Live with Saints

- 7 Find Sweet Music Everywhere

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Index