eBook - ePub

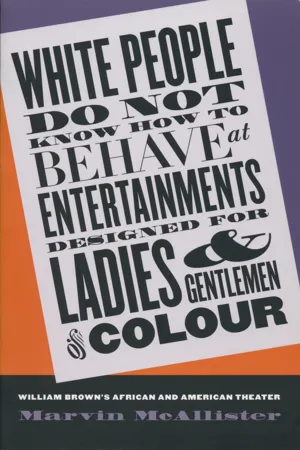

White People Do Not Know How to Behave at Entertainments Designed for Ladies and Gentlemen of Colour

William Brown's African and American Theater

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

White People Do Not Know How to Behave at Entertainments Designed for Ladies and Gentlemen of Colour

William Brown's African and American Theater

About this book

In August 1821, William Brown, a free man of color and a retired ship’s steward, opened a pleasure garden on Manhattan’s West Side. It catered to black New Yorkers, who were barred admittance to whites-only venues offering drama, music, and refreshment. Over the following two years, Brown expanded his enterprises, founding a series of theaters that featured African Americans playing a range of roles unprecedented on the American stage and that drew increasingly integrated audiences.

Marvin McAllister explores Brown’s pioneering career and reveals how each of Brown’s ventures — the African Grove, the Minor Theatre, the American Theatre, and the African Company — explicitly cultivated an intercultural, multiracial environment. He also investigates the negative white reactions, verbal and physical, that led to Brown’s managerial retirement in 1823.

Brown left his mark on American theater by shaping the careers of his performers and creating new genres of performance. Beyond that legacy, says McAllister, this nearly forgotten theatrical innovator offered a blueprint for a truly inclusive national theater.

Marvin McAllister explores Brown’s pioneering career and reveals how each of Brown’s ventures — the African Grove, the Minor Theatre, the American Theatre, and the African Company — explicitly cultivated an intercultural, multiracial environment. He also investigates the negative white reactions, verbal and physical, that led to Brown’s managerial retirement in 1823.

Brown left his mark on American theater by shaping the careers of his performers and creating new genres of performance. Beyond that legacy, says McAllister, this nearly forgotten theatrical innovator offered a blueprint for a truly inclusive national theater.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access White People Do Not Know How to Behave at Entertainments Designed for Ladies and Gentlemen of Colour by Marvin McAllister in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Late-Night Pleasure Garden for People of Color

NOAH’ S AFRICAN GROVE

FOR A MID-1980S GUEST appearance on NBC’s Saturday Night Live, Eddie Murphy and comedy writer Andy Breckman created a satiric short film, White Like Me, in which Murphy disguises himself as a Caucasian complete with whiteface makeup, a greeting card vocabulary, a straight blond wig, tight buttocks, and an intensely nasal voice. After mastering “white” form, Murphy discovers a “hidden” Manhattan where white fellows can do amazing things such as leave stores with free newspapers and secure bank loans without a whiff of collateral. Murphy’s stiff posturing and exaggerated Caucasoid dialect blatantly ridicule and caricature whiteness, but his whiteface mask generates more than easy laughs. The short film exposes and critiques the excessive entitlements, real or exaggerated, enjoyed by Euro-America, and it engages the larger problem of racial assumptions that link whiteness with plenty and blackness with lack.1 At the core of Murphy’s virtuoso performance are seemingly natural associations between whiteness, prosperity, opportunity, and educational achievement that pervade U.S. media and classrooms.2 Murphy’s performed whiteness is part of a long-standing but underdocumented performance tradition of whiteface minstrelsy.

This chapter interprets the African Grove pleasure garden as a semiprivate entertainment that deployed whiteface minstrelsy to elevate socially, and perhaps politically, the position of Afro–New Yorkers in Manhattan’s cultural landscape. In this “becoming” phase, Brown encouraged an extratheatrical performance of whiteness that allowed New World Africans to construct a distinctly black urban style and to rehearse their most coveted social aspirations. This underestimated tradition of whiteface minstrelsy first emerged in seventeenth-century New World slave cultures, eventually reached the streets of nineteenth-century New York, and finally surfaced in Brown’s African Grove. As a site of social performance, Brown’s first venture perfectly reflected Manhattan’s mutable social context marked by multiple acts of cross-racial, cross-class, and cross-caste appropriations. In white theaters and pleasure gardens, Euro–New Yorkers explored the self-creative potential of stage Indian and stage African “others.” Not surprisingly, Brown provided an attractive space for free and enslaved blacks to “other” Euro–New Yorkers and their dominant culture.

M. M. Noah initially dismissed Brown’s garden as a collection of social-climbing “colored” gentry who “generally are very imitative” and live to “ape their masters and mistresses in everything.”3 Many years later, Afrocentric scholars Carlton and Barbara Molette also dismissed Brown’s efforts, claiming his theatrical exploits “do not fully expose the beginnings of Afro-American theatre” because his company did not offer “pure African art forms.”4 But were there any “pure African art forms” available to manager Brown and his leisure-starved black patrons, and what exactly did it mean to be “African” in the early national United States? According to anthropologist Melville Herskovits, “African” in the New World signified a composite identity rooted in common cultural denominators shared by slaves from diverse West African ethnicities. Historian Sterling Stuckey further develops this composite model of “African” and claims that West and Central Africans began reconstructing an interethnic cultural identity during the traumatic Middle Passage. Aboard seventeenth-century slave vessels traversing the Atlantic Ocean, disparate groups merged religious values, linguistic elements, and artistic predilections into a syncretic “African” culture for their new home. More recently, historian Earl Lewis has extended Stuckey’s thoughts on African identity: “In the midst of the Middle Passage, words were shared, customs exchanged, and dreams of freedom planted. There and in the Americas, these ethnic people became, first, Africans and then African American—that is, they came to see and think of themselves, in relational terms, as members of a larger collective.”5 Lewis redefines or restates the composite model as an “overlapping diaspora” that resists the notion of an essential “African” and advances a diversified conception of New World blackness.

Slightly divergent from Herskovits’s, Stuckey’s, and Lewis’s composite model or “overlapping diaspora,” anthropologists Sidney Mintz and Richard Price warn that any discussion of “African” culture in the New World should not be grounded in surviving sociocultural forms but in shared values. A central “African” value that Mintz and Price emphasize—as does Brenda Dixon Gottschild—is a fundamental dynamism, a shared sense that cultural change, not stagnation, is an integral part of life.6 Mintz and Price argue that interethnic “Africans” not only recreated their Old World cultures but freely incorporated values and practices from European ethnicities in the Americas. Mintz, Price, Stuckey, Lewis, and Herskovits would all agree that New World slaves actively assimilated into an undeniably predominant Euro-American culture. Therefore, there were no “pure African art forms” for Brown’s colored actors and audiences to cultivate, and, more important, “African” in this New World could easily embody European cultural material. As an “African” value, this fundamental dynamism was best exhibited through whiteface minstrelsy.

Early national Africans in the Americas may have been exceptionally proficient at interethnic and interracial appropriation, but it would be misleading to view their various syncretisms as seamless, uncomplicated fusions of multiple African and European cultures. Historians, anthropologists, and cultural theorists have all articulated the persistent and intriguing tensions embedded in the African and American binary, as well as the potentially hybrid dynamics prevalent in colonial contexts, postcolonial moments, or other systems of domination. African American scholar W. E. B. Du Bois first articulated the New World African tension—or duality, depending on one’s perspective—of being both culturally “American” and “Negro” in the United States. For Du Bois, “American” and “Negro” represented competing directions that the “talented tenth,” those African Americans active in both white and black worlds, would have to resolve. More recently, theorist Homi Bhabha examined this encounter of seemingly competing cultures and found a hybrid fusion of the binary, a “third space,” which can serve as a transgressive mode of cultural production. Cultural critic Stuart Hall theorizes that diasporic black identities—especially Caribbean identities—are produced by three distinct cultures or “presences,” Présence Africaine, Présence Européenne, and Présence Americaine. Hall considers the American presence, his third space, the “beginning of diaspora, of diversity, of hybridity and difference” and a metaphoric “primal scene” where diasporic identities constantly produce and reproduce themselves.7

If combined, these different historical and theoretical perspectives define “African” in an early nineteenth-century United States as a complex convergence of multiple Old World African and European cultural practices and values, a fundamental dynamism that embraces difference, and a diasporic hybrid identity constantly in the act of reproduction. As for “African” institutions in the early nineteenth century, Sterling Stuckey claims some black organizations selected or were assigned the name “African” with no cultural association implied, whereas other institutions embraced the name to celebrate a continued connection to the Old World. Elizabeth Rauh Bethel argues that certain “African” societies, churches, or schools in the urban North intentionally used the term as a defining act that “publicly claimed and proclaimed both their freedom and their African ancestry.”8 In 1780s Manhattan, prompted by discriminatory practices at communion and baptisms, three African American ministers—Peter Williams Sr., James Varick, and Levin Smith—proclaimed their freedom and defected from the majority-white John Street Church. By 1795 their African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church was conducting separate religious services in a converted stable at Leonard and Church Streets on the city’s West Side. In June 1808 independent-minded Afro–New Yorkers, led by John Teasman, founded New York’s African Society for Mutual Relief to counter the perception of free black dependency on white philanthropy. This society’s primary responsibility was to keep its members and their families out of the almshouse—New York’s home for the poor and destitute—but the institution extended its resources to nonmembers.9

Culturally speaking, Stuart Hall theorizes a Présence Africaine for diasporic blacks and their institutions. Although Old World customs are ever present in African American religious and secular practices, this cultural presence is a deferred Africa, or Africa “as a spiritual, cultural, and political metaphor.”10 The African Grove, whether named by Noah or Brown, was undeniably a secular institution that personified Old World African values, and, in fact, the Grove merged a metaphoric Présence Africaine with elements of a dominant Présence Européenne to produce a most American tradition of whiteface minstrelsy.

Whiteface Minstrelsy

Whiteface minstrelsy can be understood as extratheatrical, social performances in which people of African descent assume “white-identified” gestures, dialects, physiognomy, dress, or social entitlements. Whiteface is a mimetic but implicitly political form that not only masters but critiques constructed versions of whiteness. Attuned to class as much as race, these acts tend to co-opt prestigious or elite representations of whiteness. From the time of their arrival in North America, African slaves “acted white” or mastered, celebrated, and even satirized “superior” European fashions, leisure pursuits, and other cultural forms. As Paul Gilroy suggests, “Apart from the work involved in enacting their servitude and inferiority while guarding their autonomy, people found significant everyday triumphs by mimicking and in a sense mastering, their rulers and conquerors, masters, and mistresses.”11 These “everyday triumphs” through social performance were not limited to slaves mastering masters and mistresses; free African Americans, North and South, mastered and mimicked other variations on privileged whiteness.

The term whiteface minstrelsy is an obvious play on blackface minstrelsy, but beyond the derivation of its name from blackface, my working definition owes much to recent revisions in minstrelsy scholarship. A number of performance theorists and historians have reconsidered the performative roots and social unconscious of blackface minstrelsy, and in the process these scholars have exposed minstrelsy’s working-class roots, located an attraction-aversion duality in this tradition, identified the separation of a commodified “blackness” from black culture, and even argued that minstrelsy was a forerunner to contemporary hip-hop.12 Musicologist Dale Cockrell offers this illuminating observation: “To black up was a way of assuming ‘the Other,’ in the cant of this day, a central aspect of the inversion ritual. Some of the most compelling evidence that this is in fact what happened comes from eighteenth-and nineteenth-century Caribbean John Canoe rituals, where slaves generally put on ritual whiteface theatricals personifying their Other.”13 Cockrell links blackface and whiteface in the same natural process of “othering” and understands that all New World moderns, not just Euro-Americans, constructed versions of neighboring races.

A distinct difference between whiteface and blackface lies in the dissemination and reception of these cultural products. Blackface minstrelsy, backed by the cultural sanction of white supremacy, enjoyed unlimited access to literary, visual, and theatrical outlets that circulated this uniquely U.S. form nationally and internationally. By contrast, whiteface minstrelsy—and its companion, stage Europeans—have yet to be fully recognized as legitimate forms and are only recently appearing on the radar screen of performance studies. Anthropologist John Szwed explains that white “high status minstrelizers,” in everyday life and onstage, can appropriate blackness more easily than blacks can co-opt whiteness. In fact, when blacks and other “low status” Americans adopt “the high status group’s cultural devices, [they] always risk . . . discrediting.”14 Therefore, blackface, which performed socially downward in terms of class and caste, was more readily embraced than whiteface, which performed upward. Nevertheless, before white blackface minstrel artists popularized their Zip Coons and Jim Crows, Brown’s garden patrons and his “colored” acting company were marketing their commodified versions of whiteness. Nineteenth-century audiences may have been curious about black Shakespeareans, but they were not completely aware of what they were witnessing. Some white critics, like M. M. Noah, dismissed this “low status” usurpation as simple mimicry, thus discrediting Afro-America’s tradition of performed whiteness, but whiteface was vastly more complicated.

Cockrell theorizes whiteface minstrelsy as a companion to blackface, but Joseph Roach, in his work on transatlantic performance, identifies this social practice more explicitly and distinctly. Through an insightful reading of the 1895 Plessy v. Ferguson racial accommodations case, Roach defines whiteface minstrelsy as “stereotypical behaviors—such as white folks’ sometime comically obsessive habits of claiming for themselves ever more fanciful forms of property, ingenious entitlements under the law, and exclusivity in the use of public spaces and facilities.”15 The all-white Louisiana train car serves as an outstanding example of what Roach considers “fanciful” white privilege or property. According to Roach, mulatto Homer Plessy also engaged in whiteface minstrelsy when he attempted to “pass” into that all-white conveyance and partake in the “ingenious entitlements.” These extratheatrical whiteface minstrel acts, in which whites construct entitlements and blacks appropriate them, demonstrate how African Americans could aggressively assume the privilege and cultural prestige enjoyed by Euro-America.

The relationship between Homer Plessy’s social expropriation of white entitlements, or whiteface minstrelsy, and passing is a complex one. Racial passing is a social practice by which legally defined black citizens, who visually appear white, take advantage of their biological windfall and attempt to assimilate into the majority culture. For many African Americans, in slave and postemancipation contexts, passing provided an avenue for advancement and conditional acceptance by the dominant group. Scholars have queried whether passing as a social practice represents a definitive political strategy, and they have generally agreed that it does not. Cultural theorist Amy Robinson, who has also examined the Plessy v. Ferguson case, writes that “the social practice of passing is thoroughly invested in the logic of the system it attempts to subvert.”16 A passing individual rarely challenges the “high status” culture but instead consciously dissembles to become an accepted member within that prevailing cultural group.

A passing individual must execute an exact replica of “whiteness” without the slightest deviation; remaining inconspicuous or undetectable marks a successful pass. Racial passers ultimately conform to the preexistent political-racial order or symbolic hegemony because they are conditioned by what Antonio Gramsci terms “false consciousness.” On the level of ideas, this consciousness prevents subordinates from ever thinking themselves free.17 At best, racial passing can expose the unreliability of racial categories predicated on visual markers; what you see and assume is not what you get.

Cultural theorist Michael Awkward claims that while passing reveals “the ease with which racial barriers can be transgressed,” other “texts of transraciality,” such as Murphy’s White Like Me film short, generally insist on “the impenetrability, the mysteriousness, of the racial other’s cultural rituals and social practices.”18 To the contrary, I contend that both passing and whiteface minstrelsy can demystify and familiarize white social and cultural practices. Awkward misreads Murphy’s performance of white privilege, which does comically reveal the secrets of Euro-America but ends with a satirically ominous warning that the borders can and will be transgressed by subsequent African Americans with “tons of makeup.” In fact, the whiteface minstrelsy of Homer Plessy and Eddie Murphy, more so than the implicitly invisible passing, suggests that the dominant culture’s rituals and entitlements can be penetrated or invaded.

Without question, both whiteface social performers and racial passers acknowledge the cultural primacy of Europe in the United States,...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Late-Night Pleasure Garden for People of Color: Noah's African Grove

- 2 Hung Be the Heavens with Black: Toward A Minor Theater

- 3 American Taste and Genius: Building an American Theater

- 4 Tom and Jerry Meets Three-Fingered Jack: The African Company's Balancing Act

- 5 In Fear of His Opposition: Euro–new York Reacts

- Conclusion: To Be—or Not to Be

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index