![]()

Chapter One: Setting the Stage

Antebellum and Civil War Western North Carolina

On September 1, 1867, Scottish-born botanist and naturalist John Muir set out from Jeffersonville, Indiana, on a “thousand-mile walk” to the Gulf of Mexico. Moving south through Kentucky and southeast through Tennessee, Muir studied and collected specimens of southern plant life. A Tennessee blacksmith could not believe that Muir—on his own volition and without a government commission—was simply walking through the recently war-torn South. As the blacksmith put it, Muir’s plan to “wander over the country and look at weeds and blossoms” made little sense in the tough times that followed the Civil War. Muir recorded his own thoughts about his voyage, including opinions about the environment and the people he discovered. “This is the most primitive country I have seen,” he wrote about East Tennessee and western North Carolina on September 17. When he arrived in western North Carolina, a Mr. Beale welcomed the traveler into his home in the Cherokee County seat of Murphy. Here for the first time since his trek to Florida began, Muir encountered “a house decked with flowers and vines, clean within and without, and stamped with the comforts and culture of refinement in all its arrangements.” It was, he mused, a stark difference from the “primitive” homes along the border.1

The region through which Muir passed has proven difficult to define culturally and geographically. Today, we call it Appalachia, a name derived from the Apalachee Indians and given to the region by French artist Jacques Le Moyne in 1564. When Muir completed his journey, however, he referred to it as “Alleghania,” a name used in the late eighteenth century. Around 1900, geographers adopted “Appalachia” as the term for the larger mountain range, encompassing the Blue Ridge Mountains as well as the alluvial Tennessee Valley and parts of eastern Kentucky. Regardless of its name, western North Carolina garnered special notice within this section of the South. The Old North State’s western counties possessed the nation’s highest peaks east of the Rocky Mountains, many of which clustered along the Tennessee and North Carolina borders near the Oconaluftee and Little Pigeon Rivers.2

Muir was not alone in traveling throughout the South after the Civil War. Unlike the small army of northern journalists, government officials, and other visitors, the plight of white Unionists, former slaves, and defeated Confederates had no interest for Muir. Even if little of the physical mountain landscape had changed as a result of the war, the social and cultural landscape had changed profoundly. The people Muir encountered had lived through the rise of an economically divided region that saw mountain slave owners, like their counterparts in the lowland South, capture the lion’s share of western North Carolina’s economic and political capital. The first half of the nineteenth century saw western North Carolinians develop strong economic ties with the southern cotton economy, which led a majority of white western Carolinians into the war for southern independence. Despite internal divisions among its population, western North Carolina contributed its share of men and materiel to the Confederate war effort. In the end, however, that conflict exploded the localized antebellum political culture. The strains of war—the absence of many military-aged white men, weakening bonds of slavery, localized guerrilla violence, strong national governmental policies—“opened” the region to a variety of external sources of power that threatened elite whites’ domination of the region.

Many travelers like Muir noted the raw beauty of the southern mountain landscape, but the region had also been home to humans for centuries. Its first residents were Mississippians, a cultural group characterized by their large earthen mounds and central temples. These earlier chiefdoms evolved into the indigenous populations encountered by Europeans in the 1500s. Spread across parts of North Carolina, Georgia, Tennessee, and South Carolina, the Cherokee were the most powerful Native American group within Southern Appalachia.3 In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, many Scots-Irish immigrants came to America to escape the rigidity of society in Northern Ireland where, like much of Europe at that time, a small landholding class exercised vast economic and political control over a landless laboring class. Migrating slowly from Pennsylvania into Virginia and western North Carolina, the Scots-Irish settled the fertile river valleys that served as the easiest means of travel and trade, making western North Carolina’s early white pioneers successful farmers and merchants. Slavery soon followed. Although some mountain masters, such as the Pattersons of Caldwell County, fit within the state’s wealthiest slaveholding population, the majority of highland slave owners fell within a middle class of commercial farmers, merchants, manufacturers, artisans, and small-scale professionals with fewer than twenty slaves. Wealthy, business-oriented mountaineers recognized the economic advantages of slavery and used the revenue from their various business ventures to purchase and employ their slaves.4

Not large planters in the same vein as slave owners in the Deep South and Cotton Belt, mountain slaveholders exhibited a level of political and economic control comparable to the broader southern gentry. One-fourth of all white families in the plantation South owned slaves and controlled over 93 percent of that section’s total wealth. North Carolina’s mountain slaveholding class also owned large amounts of land. In northwestern North Carolina, Ashe County’s eighty slaveholders owned a disproportionate 28 percent of the improved farm acreage in the 1850s. Parallel situations existed throughout the Carolina highlands, where slaveholders commanded 59 percent of the total wealth. The smaller percentage of mountain slaveholder-controlled wealth is misleading because western North Carolina slave owners made up only one-tenth of the region’s white families. Hence, mountain slaveholders possessed a higher comparative percentage of their region’s total wealth compared to their plantation counterparts.5

Yeoman farmers, who owned land but few if any slaves, constituted a far greater portion of the mountain populace. The earliest white settlers’ occupation of the rich bottomlands and reliance upon open-range livestock pushed these settlers onto less fertile land, where they settled into a predominantly local system of exchange. Whereas yeomen living in the plantation districts were often bound to local planters for economic assistance, the independent small farmers outside the Black Belt relied on one another. Large-scale agricultural projects requiring intensive labor, such as clearing trees, became community functions joining local yeomen together. Despite their settlement of more remote mountain areas, Southern Appalachian yeomen were not isolated. East Tennessee farmers shared many characteristics with their counterparts across the mountains in western North Carolina. Hog drives proved extremely profitable for farmers in both regions and served to tie small farmers to Lower South markets. Following the completion of the East Tennessee and Georgia and the East Tennessee and Virginia Railroads by 1855, the entire East Tennessee Valley had rail access. Farmers began producing wheat largely for markets. Without a railroad, western North Carolina farmers remained committed to livestock production. The absence of a viable cash crop, such as cotton, prevented the formation of typical southern plantations and promoted agricultural diversity. Rough terrain and a cooler climate allowed grains to thrive where cotton floundered. Cattle, sheep, and hogs proved especially profitable because they adjusted well to mountain conditions. In addition, cotton’s dominance in the Lower South increased the demand for foodstuffs from the Upper South. Since mountain farmers traditionally produced an abundance of food, it was only a matter of directing that surplus to market. Hence, western North Carolinians had a strong interest in the success of the staple crop.6

Landless white tenants rested below the yeomen in the southern social hierarchy. Tenancy was on the rise throughout the South during the late antebellum period. Sociologist Wilma Dunaway has argued that landless tenants were essential to the settlement of Southern Appalachia. Land speculators purchased large tracts of Southern Appalachia through the final decades of the eighteenth century, which Dunaway claims rendered three-fourths of the total acreage in the highlands the property of absentee owners. This speculative trend, begun in western North Carolina in 1783, made it difficult for small farmers to acquire land legally. Dunaway concludes that this combination of absentee owners and landless settlers “entrenched [tenancy] on every Southern Appalachian frontier.” Still, the material differences between landless whites and landowning yeomen were subtle. Both groups worked small tracts of land for personal use and raised livestock with similar rewards. Renters enjoyed a degree of freedom denied yeomen. Because their labor agreements were temporary, tenants could leave a bad situation, and they did not pay property taxes. Such benefits exacted a price. Landless tenants lacked the security and independence of the landowning yeomanry. Poor landless whites were subjected to evictions, biased written contracts that favored their employers, and the confiscation of their crops by creditors.7

Class conflict remained muted before the Civil War in western North Carolina, despite the declining position of landless whites. As was the case throughout the South, family ties eased social tensions. Intermarriage among the region’s wealthiest families fostered bonds that solidified the slaveholders as a class. For example, the influential Lenoir family of Caldwell County linked several of the western counties’ most powerful families. Revolutionary War veteran and early settler William Lenoir’s children and grandchildren brought the Lenoirs together with the Avery family of Burke County, the Joneses and Gwyns in Wilkes County, as well as their Caldwell County neighbors the Pattersons. Still, the slave-owning elite remained mindful of their largely nonslaveholding constituents. Political campaigns created personal relationships between lower-class voters and wealthier neighbors who hosted visiting candidates and organized meetings. Perhaps it was the region’s lack of a true planter class that most effectively fostered unity among mountain whites. Though mountaineer masters dominated the region’s politics—87.1 percent of the men elected to the state legislature between 1840 and 1860 owned slaves—their diverse economic interests created common ground with their community. Middling and lower-class whites in the upcountry and mountain sections supported slaveholders politically because they pushed for the region’s recognition and development at the state level. More broadly, the slaveholders’ promotion of states’ rights staved off outside power—primarily the federal government—and allowed lower-class whites more autonomy within their lives and communities.8

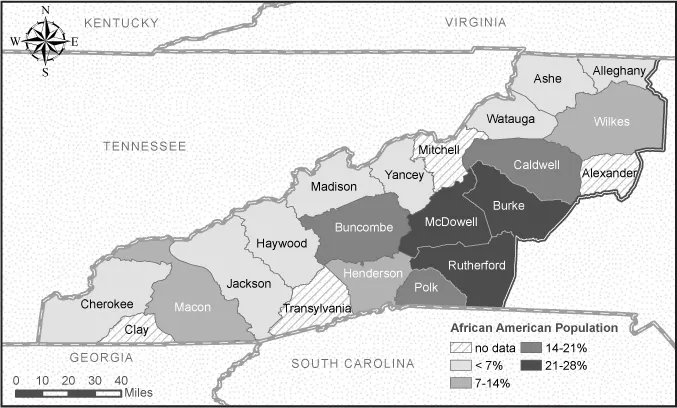

MAP 2. African American Population in Western North Carolina, 1860. Map produced by Andrew Joyner, Department of Geosciences, East Tennessee State University.

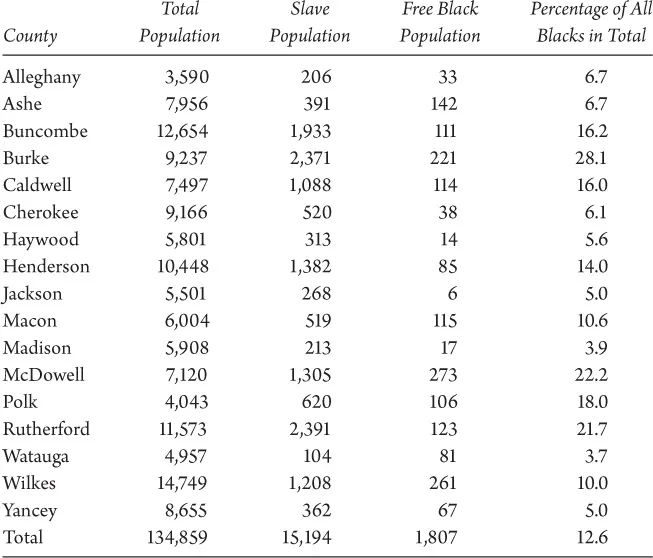

Slaves occupied the lowest rung on the social ladder in the southern mountains, just as they did throughout the South. Yet African Americans in the western counties lived differently from their plantation counterparts. One reason for the difference was mountain slaves’ comparatively small percentage of the population (see Map 2 and Table 1). The white majority feared slave rebellions less and allowed their chattel more mobility throughout the region. Some mountain slaves served as guides for summer tourists. Slave owners in western North Carolina were less likely statistically to employ corporal punishment, and also less inclined to separate slave families through sale. Still, such benefits only altered, not negated, the exploitive characteristics common to the southern slave system. For example, historian Edward Phifer found sexual exploitation of slave women as common in Burke County as elsewhere in the South. Neither did living in western North Carolina remove the psychological scars inflicted by being classified as property.9

TABLE 1 African American Population in Western North Carolina Counties, 1860

Note: Clay, Mitchell, and Transylvania Counties formed in 1861. See Corbitt, Formation of the North Carolina Counties 1663–1943, 67, 149, 204.

Sources: Inscoe, Mountain Masters, 61; and Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research, Historical, Demographic, Economic, and Social Data (computer file).

While the basic contours of society in the mountain South paralleled the section as a whole, mountain residents generally outpaced their lower-elevation compatriots in their support for internal improvements. Western North Carolinians believed their region was on the rise, and they urged the state to support projects that facilitated their growth. Turnpikes, such as the highly traveled Buncombe Turnpike completed in 1828, became a top priority in the 1830s and 1840s. But opposition from the eastern part of the state—such sectional rivalry within the state was a defining trait of the state’s antebellum politics—threatened western development. Eastern North Carolinians refused to pay the taxes necessary to fund such projects because they failed to see how they benefited from western improvements. The discovery of valuable mineral resources in southwestern North Carolina and East Tennessee’s success with mining and railroads led western Carolinians to explore all possibilities to obtain their own railroad. By the 1850s the issue garnered such popular backing that both mountain Whigs and Democrats supported it. Finally in 1855, western North Carolina secured a charter and a $4 million state appropriation for the Western North Carolina Railroad (WNCRR). That high price, however, forced the construction of the road in segments, with the completion of one part to precede the construction of the next.10

During the 1830s and 1840s, the Whig Party’s commitment to internal improvements contributed to the party’s consistent popularity in western North Carolina; however, an economic depression limited the state’s spending power for much of that period. One Whig member of the state assembly believed that North Carolina would have to raise taxes fivefold in order to finance its desired internal improvements, an unsavory idea for any politician. Consequently, the Whigs were unable to deliver funding for improvement projects during that time. Realizing that proposed railroads through western North Carolina by both South Carolina and Virginia would divert mountain trade out of the state, Democrats dropped their opposition to state-funded internal improvements. The Whigs’ inability to receive public funds for western improvement projects, along with the orchestration of the WNCRR’s creation by a Democratic governor, hurt but did not destroy them. By 1860, the Whigs had slipped in terms of their influence within western North Carolina, but their commitment to internal improvements sustained them as political players in the mountains even after their national party collapsed in the mid-1850s.11

Two political issues heightened the state’s internal east-west rivalry and stirred class tensions during the late antebellum period. The state constitution apportioned the upper legislative house according to taxes paid and the lower house based on federal population, including slaves as three-fifths of a person. This system concentrated power in the plantation-dominated eastern counties. In 1848, Democratic gubernatorial candidate David Reid proposed the elimination of the property qualification that limited the political voice of lower-class Carolinians. Mountaineers demanded a constitutional convention to convert the basis of representation in the lower house to conform to Reid’s proposal. Failure to support the convention weakened the mountain Whigs and brought Reid’s Democrats to power in the state. Chastised by the voters, Whigs regrouped in a convention in Raleigh in 1850. The resulting pamphlet known as “The Western Address” challenged the dominance of a propertied—especially slaveholding—elite at the expense of lower-class whites. By the end of the antebellum period, the Whigs further regained lost ground through support of ad valorem taxation, touted by Whigs as “equal taxation.” Eastern planters opposed the proposal because it would tax all slave property according to value, whereas the existing poll tax only assessed male slaves between twelve and fifty years old. Although nonslaveholders became indignant that their wealthier neighbors would not carry their share of the tax burden, the Democrats successfully convinced nonslaveholders that ad valorem taxation represented governmental encroachment upon individual property rights and would increase the taxes on all property—not just slaves. Still, the issue helped restore the two-party balance in the mountains on the eve of disunion.12

The turbulent presidential election of 1860 revealed white western Carolinians’ complex self-image. Although westerners within North Carolina, their opposition to the Republican Party in the 1860 presidential election revealed them as southerners within the United States. In western North Carolina and the South, the election centered on John C. Breckinridge, a southern rights Democrat, and John Bell, of the mo...