eBook - ePub

Trench Warfare under Grant and Lee

Field Fortifications in the Overland Campaign

- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Earl J.Hess's study of armies and fortifications turns to the 1864 Overland Campaign to cover battles from the Wilderness to Cold Harbor. Drawing on meticulous research in primary sources and careful examination of battlefields at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, North Anna, Bermuda Hundred, and Cold Harbor, , Hess analyzes Union and Confederate movements and tactics and the new way Grant and Lee employed entrenchments in an evolving style of battle. Hess argues that Grant's relentless and pressing attacks kept the armies always within striking distance, compelling soldiers to dig in for protection.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Trench Warfare under Grant and Lee by Earl J. Hess in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Storia & Storia della guerra civile americana. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Engineer Assets in the Overland Campaign

By the spring of 1864, the commanders of the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia could rely on three years of experience with organizing and using their respective engineer assets. The Federal government entered the war in 1861 with a minuscule cadre of engineer officers and one company of engineer troops. Both were enlarged in the ensuing years. The Confederate government had started the war with nothing but soon created a small corps of engineer officers that was later expanded. The Southerners waited until 1863 to organize engineer troops. One thing both Union and Confederate armies in Virginia had in common was that they tended to be allocated the lion’s share of engineering resources available to their respective governments.

FEDERAL ENGINEERS

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers witnessed a change of leadership just before the start of the Overland campaign. Brig. Gen. Joseph G. Totten, who had led the corps as chief engineer since 1838, died of pneumonia at age seventy-six on April 22, 1864. He was replaced by Richard Delafield, who received a promotion to brigadier general as a result of his new assignment. Delafield, only ten years younger than Totten, was another venerable member of the corps. He had been one of three officers sent by Secretary of War Jefferson Davis to study European military systems during the Crimean War.1

Although the corps leadership consisted of elderly men past their prime as field engineers, the Federals had enough young, energetic subalterns to fill the needs of the Army of the Potomac. Of the 86 engineer officers on duty in early 1864, 21 were assigned to the east while only 9 were with Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s army group in Georgia. The engineer officers with Grant and Meade tended to be young; some of them were fresh out of West Point and thrust into assignments with minimal field experience.2

James Chatham Duane, born on June 30, 1824, in Schenectady, New York, served as chief engineer of the Army of the Potomac during the Overland campaign. His father had been a delegate to the Continental Congress, mayor of New York City, and a delegate to the convention that ratified the U.S. Constitution. Duane graduated from West Point in 1848 and was commissioned in the Corps of Engineers. He taught at the academy and commanded the U.S. Army’s only engineer company on the Utah expedition against the Mormons in 1857. He led the enlarged U.S. Engineer Battalion during the Peninsula campaign and served as Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s chief engineer during the Maryland campaign. Transferred south in January 1863, Duane experienced the special problems associated with operating along the Georgia and South Carolina coast until returning to the Army of the Potomac as chief engineer on July 15, just after Gettysburg. He continued in this position until the end of the war, although his rank never caught up with his responsibilities. Promoted to major in July 1863, he never rose higher than a brevet rank as brigadier general before the war ended. After Appomattox, Duane mostly served on lighthouse duty, although he was chief engineer for two years before his retirement in 1888. Duane died in 1897 at age seventy-three.3

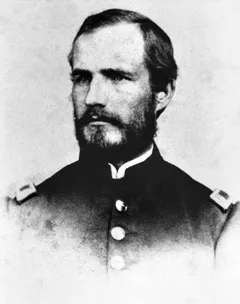

Grant also had an engineer officer on his U.S. Army headquarters staff during the Overland campaign. Born in 1831 in Massachusetts, Cyrus B. Comstock graduated first in the West Point class of 1855; he served at various coastal forts and taught at the academy before the war. Comstock worked on the defenses of Washington, D.C., was a subordinate engineer officer during the Peninsula campaign, and served as chief engineer of the Army of the Potomac from November 1862 until March 1863. His transfer west brought him into Grant’s orbit, and he served for a time as chief engineer of the Army of the Tennessee. When Grant went east in March 1864, he took Comstock along as his senior aide-de-camp. As such, Comstock became one of the more influential advisers of Grant’s entourage, at least according to the testimony of other staff officers and commanders. Brig. Gen. John A. Rawlins, Grant’s chief of staff, blamed Comstock for the series of often ill-prepared attacks against fortified Confederate positions at Spotsylvania and Cold Harbor. Grant valued Comstock’s opinion and sometimes used him as a liaison with his subordinates. Comstock’s influence was felt on a far wider scale than the technical issues that normally occupied Duane’s time.4

Junior engineer officers, such as George L. Gillespie, labored diligently at those technical issues as well. Born at Kingston, Tennessee, in 1841, Gillespie graduated second in his West Point class of 1862 and was assigned to the Army of the Potomac three months later. He was awarded the Medal of Honor for his exploits in carrying a dispatch from Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan to Meade on May 31, 1864, during the Cold Harbor phase of the Overland campaign. He was captured but escaped, then was nearly captured a second time but managed to reach Meade’s headquarters with important information. After the war, Gillespie served for a time as chief of engineers. He also designed the standard version of the Medal of Honor, in use ever since 1904, while serving as assistant chief of staff of the army. Gillespie died in 1913.5

Cyrus Ballou Comstock. (Roger D. Hunt Collection, U.S. Army Military History Institute)

James St. Clair Morton was an outstanding engineer who saw service in the Overland campaign. Born in Pennsylvania, he graduated from West Point in 1851 and served at various coastal and river forts. He was chief engineer of the Army of the Ohio (later designated the Army of the Cumberland) from June 1862 until November 1863. Morton commanded the Pioneer Brigade of that army during much of this time as well. Wounded at Chickamauga, he later became an assistant to Chief Engineer Totten in Washington, D.C., then was appointed chief engineer of Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside’s Ninth Corps on May 18, 1864. Morton lacked many of the social graces but was widely respected for his skill, energy, and personal bravery. The latter quality led to his death on June 17, 1864, during the first round of fighting at Petersburg. His loss left a hole on Burnside’s staff that was never adequately filled.6

These engineer officers not only laid out and supervised the construction of fieldworks, they did a variety of other tasks as well. The demand for maps of the Virginia countryside occupied the topographical talents of many engineer officers. Also, given the paltry number of staff officers assigned to corps and division leaders, engineers often were called on to perform duties unrelated to engineering. They frequently were shifted from one headquarters to another, as needed. In the words of Capt. George H. Mendell, who commanded the U.S. Engineer Battalion, they were “almost constantly employed in reconnaissances, … in guiding troops to positions, and performing such other staff duty, as the corps commanders desired.”7

The engineers assigned to the Army of the James also struggled to meet the challenges of the Overland campaign. Francis U. Farquhar, a Pennsylvanian who graduated from West Point in 1861, served as chief engineer for Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler. He had earlier been an aide-de-camp on Brig. Gen. Samuel P. Heintzelman’s staff at First Bull Run, was with McClellan on the Peninsula, and then went south to become chief engineer of the Department of Virginia and North Carolina. He took the field with Butler’s Army of the James, but poor health led to his reassignment on May 17, 1864. Farquhar, who was a friend of Lt. Col. Henry Pleasants, the digger of the famous mine at Petersburg, then became chief engineer of the Eighteenth Corps in Butler’s army until health problems ended his war career. He taught at West Point during the last months of the conflict and worked on many civic projects after the war. Farquhar died in 1887 at the age of forty-five.8

Another engineer serving with the Army of the James was Peter Smith Michie, who had been born in Scotland in 1839. Migrating with his family at age four, Michie attended a high school in Cincinnati, Ohio, and then graduated second in his West Point class of 1863. He was immediately sent to Morris Island, where he worked on the siege approaches to Battery Wagner. Maj. Gen. Quincy A. Gillmore took him along to Virginia, where he later became chief engineer of the Army of the James. Michie taught at West Point after the war until his death in 1901.9

The Corps of Topographical Engineers, in existence since 1818, was merged with the Corps of Engineers in 1863. Thus, for the Overland campaign, topographical duties were shared by all engineer officers in the

Francis Ulric Farquhar. (Massachusetts Commandery, Military Order of the Loyal Legion and the U.S. Army Military History Institute)

Army of the Potomac, but Nathaniel Michler took charge of mapping. Born in Pennsylvania, he graduated seventh in the West Point class of 1848 and was commissioned in the Topographical Engineers. Michler quickly made a reputation in mapping, surveying, and geographic exploration. He worked on a number of projects, including the U.S.-Mexico boundary survey, initial efforts to plot a course for a proposed canal across Panama, and reconnaissance forays across Texas. As captain of engineers, he served in the Army of the Ohio and the Cumberland until transferred east in 1863. Michler was captured by Confederate cavalry while making his way to the Army of the Potomac but was soon exchanged. He filled in as chief engineer for Meade in the fall of 1864, when Duane took a sick leave. Michler ended the war with a brevet commission as brigadier general. After the conflict he supervised public buildings in the District of Columbia, among a variety of other duties, and died in 1881 at age fifty-three.10

Michler prepared for the Overland campaign by overseeing the compilation of twenty-nine maps, to the scale of one inch per mile, covering the region between Gettysburg, Petersburg, the Chesapeake Bay, and Lexington, Virginia. He combed all available sources, including previous work by army engineers and U.S. Coast Survey maps, for topographical data. Michler’s sheets were sent to Washington to be reproduced by photography, lithography, or engraving. In addition to these maps, which were distributed to commanding officers, several other series of previously compiled maps were reproduced for distribution.

Yet, all this preparation was inadequate. Michler soon realized that these maps were not detailed or accurate enough to enable commanders to select defensive positions or prepare marching orders and plan routes of advance. The countryside on which the Overland campaign was played out was “of the worst and most impracticable character—a most difficult one for executing any combined movement.” Not even the Confederates had adequately detailed information, for the Federals often saw Rebel mapping parties at work during the campaign. Michler had to do the same, and his assistants anticipated the needs of the army and tried to probe forward as far as possible without getting shot or captured. Michler had two officers assigned to him, plus seven civilians and several enlisted men detailed from the ranks of various regiments. These men provided a constant stream of information that was used to update and correct preexisting maps, resulting in “several editions” of the general map Michler had prepared before the start of the campaign. The members of his crew were very busy from May 4 until the explosion of the Petersburg Mine on July 30, one and a half months following the close of the Overland campaign. They had already issued 1,200 maps to the Army of the Potomac even before May 4 and supplemented them with an additional 1,600 maps after that date. The men conducted “over 1,300 miles of actual surveys” to produce these maps.11

Col. Theodore Lyman, an astute member of Meade’s staff, found these maps to be less than all that was needed by the army, even though he realized the enormous effort expended to make them. The maps were “printed in true congressional style on wretched spongy paper, which wore out after being carried a few days in the pocket.” After the war, Lyman compared them with a map produced by army engineers in 1867 to the scale of three inches to the mile. Compiled in peacetime, with opportunities for careful study and in a scale that allowed for greater detail, Lyman found these newer maps to be far more accurate in the configuration of streams and in the location of specific points of interest. Michler’s wartime maps were accurate only in a general way—“in the distances and directions of the chief points.” Smaller but significant points, such as Todd’s Tavern and the house of S. Alsop, were as much as one and a quarter miles off their true location. The configuration of many roads was so far off as to be “quite wild.” Lyman spared no words when he wrote that the “effect of such a map was, of course, utterly to bewilder and discourage the officers who used it, and who spent precious time in trying to understand the incomprehensible.”12

Michler’s men could do a much better job on maps depicting battlefields of the immediate past. After the armies moved south of the North Anna River, Duane instructed Michler to thoroughly map the battlefield there. Lt. Charles W. Howell led three assistants in surveying the ground over the course of three days. Men detailed from the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry held flags and tapes to aid the survey, and protected the party from possible guerrilla attacks. This map, later published in the atlas to accompany the War Department’s publication of official reports and dispatches, is detailed and relatively accurate.13

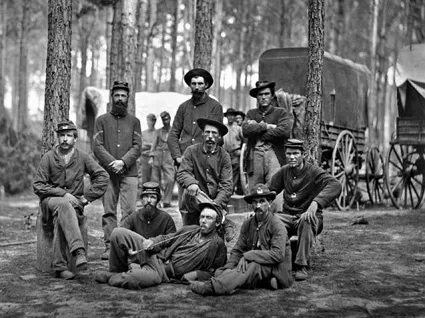

The contingent of engineer officers serving with the Army of the Potomac was huge compared to that serving under Sherman in the west, but actually it was barely large enough to handle the many and varied tasks of the army. The Army of the Potomac had more engineer troops than any other Union field army. The U.S. Engineer Battalion consisted of four companies—one predating the outbreak of war and the other three organized after Fort Sumter. By 1864, the Volunteer Engineer Brigade consisted only of the 50th New York Engineers. Both units had served consistently with the Army of the Potomac since before the Peninsula campaign. The 15th New York Engineers also belonged to the Volunteer Brigade, but it was on detached duty at the Engineer Depot in Washington, D.C. Butler’s Army of the James had the services of eight companies of the 1st New York Engineers under Col. Edward W. Serrell during the Bermuda Hundred campaign. The other four companies remained in the Department of the South, stationed primarily at Hilton Head, Folly Island, and Morris Island. Butler also used a company of the 13th Massachusetts Heavy Artillery to manage his pontoon train.14

Members of Company B, U.S. Engineer Battalion, August1864. (Library of Congress)

Both the U.S. Engineer Battalion and the Volunteer Engineer Brigade were commanded by regular engineers, Capt. George H. Mendell and Brig. Gen. Henry W. Benham respectively. Benham also was on detached duty at the Engineer Depot, allowing Lt. Col. Ira Spaulding, who commanded the 50th New York Engineers, to report directly to Duane. Born in Oneida, New York, Spaulding was already forty-six years old when the Overland campaign began. “He knew nothing of military matters when he joined the Regiment,” recalled Wesley Brainerd, a friend and fellow officer, “and served devoid of any ambition except to perform well the duties of Captain.” Spaulding was a strong but unassuming personality, “one of the wiry kind that could stand a great amount of fatigue and thrive under it.” He had no difficulty transferring his skill as a civil engineer to the military realm. Spaulding was promoted major in November 1862 and lieutenant colonel in June 1863; he ended the war as brevet colonel. Though his health broke after the war, he worked for a time as chief engineer of the Northern Pacific Railroad but died in 1875 of heart disease.15

Ira Spaulding. (Massachusetts Commandery, Military Order of the Loyal Legion and the U.S. Army Military History Institute)

Spaulding’s friend, Wesley Brainerd, was born in Rome, New York, in 1832. He received an academy education and worked as a draftsman for the Norris Locomotive Works in Philadelphia. Moving to Rome as a businessman before the war, Brainerd recruited a company for the 50th New York Engineers and rose to the rank of colonel by the end of the war. He even led the Volunteer Engineer Brigade for a time in February 1865. After the war, Brainerd worked in the lumber business at Chicago, where he helped to fight the great fire of 1871. Later he entered the iron smelting business and got involved in mining operations in Colorado. Brainerd died in 1910.16

Rather than keep the 50th New York Engineers intact, Duane divided it into four battalions for the Overland campaign. Three of those battalions had three companies each, wh...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Trench Warfare under Grant & Lee

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Preface

- 1 Engineer Assets in the Overland Campaign

- 2 The Wilderness

- 3 Spotsylvania, May 8–11

- 4 The Mule Shoe Salient at Spotsylvania, May 12

- 5 Spotsylvania, May 13–20

- 6 Bermuda Hundred

- 7 North Anna

- 8 Cold Harbor, May 27–June 2

- 9 Attack and Siege—Cold Harbor, June 3–7

- 10 Holding the Trenches at Cold Harbor, June 7–12

- Conclusion

- Appendix The Design and Construction of Field Fortifications in the Overland Campaign

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index