![]()

CHAPTER ONE

A Slave Society

Virginia in the 1850s

Late antebellum Virginia, like the rest of the South, had long existed as a “slave society” rather than a “society with slaves.”1 Slavery infused the commonwealth’s social and political institutions, constitutional system, and methods of agriculture, commerce, and industry. Although tobacco culture had passed into relative decline, the institution of slavery displayed remarkable resiliency. Despite the exodus of thousands of slaves to the Deep South, the expansion of slave hiring, and the presence of a sizable free black population, slavery moved in lockstep with dynamic economic forces of the 1850s. Especially during this decade, the Transportation Revolution expanded markets, spread commercial agriculture, fostered manufacturing, extended mining, and, not the least important, reinvigorated slavery’s economic position. Wherever dynamic market forces made an appearance, slavery accompanied them, and, far from verging on extinction on the eve of the Civil War, the peculiar institution in Virginia remained adaptable, viable, and modernizing. The evidence of slavery’s resiliency can be found not only in rising slave prices but also in the use of slave labor for various enterprises. Nonetheless, economic change fundamentally altered the peculiar institution’s social position. During the late antebellum years, significant changes arising from the changing economic system—particularly the use of unsupervised slaves working in factories as well as of hired slaves—sometimes undermined Virginia’s traditionally paternalistic system of controlling its slaves.

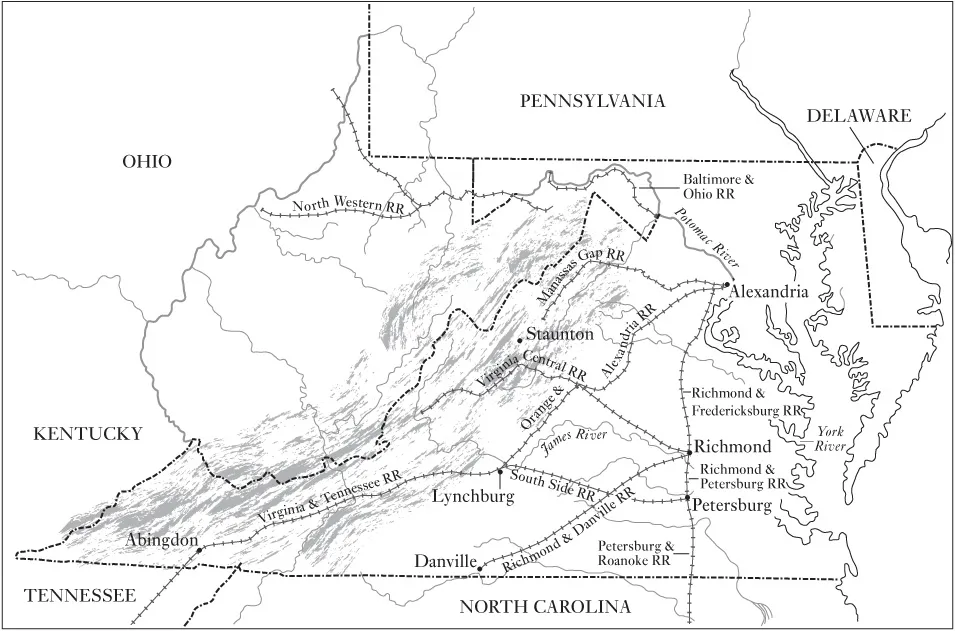

Like most of America, Virginia experienced profound changes during the pre–Civil War era. Canals linked coastal ports with interior goods and markets; the most prominent, the James River and Kanawha Canal, was organized in 1785 and was meant to connect Richmond with western Virginia. Subsequently, the General Assembly would authorize other projects in river and harbor improvements, bridge building, and road and turnpike construction.2 Beginning in the 1830s and 1840s, railroad construction accelerated rapidly, and, all told, by the outbreak of the Civil War the state had contributed nearly $45 million toward railroad construction. During the 1850s, existing railroad track in Virginia grew from 350 to 1,350 miles, and the Virginia Board of Public Works could justly boast of a “revolution in public opinion” regarding the commonwealth’s internal improvements.3

The beginnings of a railroad network had a marked effect, especially in making towns into larger market centers. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad connected the Ohio River Valley to Baltimore and contributed to the growth of Wheeling as the largest town in northwestern Virginia, while the North Western Railroad connected Grafton on the B&O to Parkersburg on the Ohio River. Already a center of the Potomac River and Chesapeake Bay trade, Alexandria competed furiously for the commerce of the Shenandoah Valley and northern Piedmont through the seventy-seven-mile Manassas Gap Railroad and the thirty-seven-mile Alexandria, Loudoun and Hampshire Railroad. Petersburg gained better access to markets in southern Virginia and North Carolina’s Roanoke River valley through the Petersburg Railroad. Lynchburg benefited from the southern extension of the Orange and Alexandria Railroad, and the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad, which connected it southwest to Bristol and ultimately Tennessee. The Virginia Central ranged 195 miles between Richmond, Charlottesville (central Piedmont), and Staunton (central Valley), terminating in Jackson’s River, at the gateway of the mountain region. By the end of the 1850s, the South Side and the Richmond and Danville Railroads connected the southern Piedmont plantation region to markets in Lynchburg in the west and Petersburg and Richmond in the east.4

Significant social change followed the expanding transportation network. The state’s population grew by nearly a third between 1840 and 1860, with a marked increase in white population west of the Blue Ridge. Both white and black populations grew by natural increase, despite heavy outmigration from the state. Migration across the Blue Ridge heightened sectional differences, as western Virginia became whiter and eastern Virginia, blacker. By 1860 the West contained nearly three-fifths of the state’s white population, while the East accounted for more than four-fifths of the state’s African American population. Economic growth was pronounced in areas affected by internal improvement. Market agriculture was particularly prominent along estuaries of the James, York, Rappahannock, and Potomac Rivers. Away from these river systems, according to a contemporary, commercial farming became “less and less marked,” though the advent of railroads was “destroying this difference.”5 Commercial agriculturists pressed for improved transportation along with a redefinition of property rights, including the revision of fencing laws and restrictions on traditional access to common pasture lands. The slave economies of the Piedmont and the Tidewater prospered; some eastern counties profited from increasing investment in market-garden agriculture. Valley farms remained the richest in the state, while those in the Trans-Alleghany were the poorest; primarily subsistence farmers and stock raisers, northwestern Virginians became even poorer relative to the rest of the state. There was also a growing difference among areas surrounding Virginia’s towns and cities, where farmers produced garden vegetables for market.6

MAP 1.1. Railroads of Virginia, 1858

TABLE 1.1. Total Value of Market Gardens, Leading Virginia Counties |

|

| County | 1850 | 1860 | % Change |

|

| Prince George | $3,336 | $7,325 | 120 |

| Amherst | 200 | 9,242 | 4521 |

| Chesterfield | 2,540 | 10,244 | 303 |

| Fairfax | 3,168 | 12,605 | 298 |

| Nicholas | 0 | 13,733 | |

| Ohio | 6,167 | 14,420 | 134 |

| Arlington/Alexandria | 16,120 | 28,970 | 80 |

| Hanover | 9,290 | 52,645 | 467 |

| Henrico | 39,976 | 80,280 | 101 |

| Norfolk | 53,512 | 292,968 | 447 |

|

Source: Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research, University of Michigan

In the railroad-driven market economy, urban Virginia hummed with activity. In eastern Virginia, Richmond solidified its status as the commonwealth’s leading city, and its connection to key canals and railroads fueled its rapid growth. As a center of trade, finance, and transportation, Richmond had become the leading manufacturing city in the late antebellum South, and its iron foundries and tobacco factories achieved a prominent place in the cityscape. Petersburg, with an aggressive group of entrepreneurs, achieved importance in trade, transportation, and cotton textile and tobacco manufacturing. By 1860, it ranked among the top fifty manufacturing cities in the United States.7

Overall, the 1850s were a decade of steady economic growth associated with railroads and market economic forces. Large cities experienced notable population increases, especially in white population, as the state’s three largest cities—Richmond, Petersburg, and Norfolk—watched their population grow by a fifth during the decade. Population growth reflected heightened economic activities in urban areas. Virginians interested in commercial development and access to a growing international market realized that future growth depended on railroads. A Norfolk observer noted the “happy effects” of the transportation boom. “Scarcely a day” passed, he wrote, “but that a quantity of produce of various kinds—cotton, bacon, peas, &c.”—was being brought to Norfolk’s market. All “traffic of this kind” would increase from the “association and proximity with the section of the country” where it was produced.8

TABLE 1.2. Urban Growth in Virginia, 1850–1860 |

|

Size of Town

(Pop.) | Total

(% Change) | White

(% Change) | Slave

(% Change) | Free Black

(% Change) |

|

| 0–1,000 | 20 | 18 | 23 | 85 |

| 1,000–2,500 | -2 | 16 | -26 | -69 |

| 2,500–10,000 | 9 | 21 | -21 | 13 |

| 10,000+ | 27 | 38 | 5 | 13 |

| Total | 20 | 31 | -3 | 1 |

|

Source: Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research, University of Michigan

Many Virginians were amazed at the rapidity and ease with which they could traverse the state, compared with the prerailroad era. “Almost magical results” flowed out of state support of railroads, declared the Richmond Whig, for Virginians realized that, without them, state residents would be “outstripped in the race of improvement, and soon be left in a condition of hopeless inferiority, political and otherwise.” The advent of railroads excited a frenzy across the commonwealth. Communities knew that their future lay with railroads; in many instances they were importuned for stock subscriptions to finance the burdensome costs of construction.9 Local competition for railroad access dominated legislative politics. The stakes were high. The construction of the South Side Railroad, and particularly its connection with lines westward and northward, commented one observer, determined future prosperity. The South Side’s construction affected communities throughout the southern Piedmont. Routing this railroad so that it traveled through Farmville, one legislator observed in 1851, meant that that town “would have a chance at a trade and travel which she never has commanded & never can command without that line.”10

Many observers marveled at how railroads seemed to conquer nature. South of Charlottesville, construction crews were described in 1857 as “busily engaged excavating, shoveling and carting earth, blasting, constructing stone supports for bridges across small streams, and generally in preparing the way for the iron horse with his speed and power.” Railroads’ ability to conquer previously insurmountable physical obstacles seemed obvious testaments to their power. In the mid-1850s, the construction of the Virginia Central’s Blue Ridge Tunnel—a cut through the mountains of some 4,248 feet in length—symbolized the victory of humans over nature. In August 1858, an observer told how the North Western Railroad had constructed more than twenty tunnels through the “immense labor” of the “poor laborious fellows who for a small pittance risked their lives boring through those everlasting rocks, and thereby increasing our commerce and enriching our land.” Who would have believed, even eight or nine years earlier, that “the distance from Parkersburg to Grafton would at this day be traveled in the incredible short time of four or five hours, notwithstanding the many obstacles presented on this route?”11

The early and often sensational appearance of railroads was rooted in an obsession with both technology and wealth. As one Abingdon newspaper noted in 1851, the “very anticipation” of the completion of the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad increased local property values by a third. When the Richmond and Danville Railroad reached Amelia Court House, local citizens organized a barbecue. In attendance were about 300 women, and, according to one account, an excursion train loaded with residents and Richmonders traveled to the Appomattox River in order to view a newly completed iron bridge. They returned to Amelia, where they partook of the villagers’ “good cheer,” heard speeches at the courthouse, and then ate dinner. At nightfall, out-of-town guests returned to Richmond, with a travel time of about two hours. Two years later, in August 1853, a similar celebration greeted the opening of a new twelve-mile section of the Virginia and Tennessee between Salem (near present-day Roanoke) and Big Springs, in Montgomery County. An excursion train left Lynchburg at 7:00 in the morning, with 100 passengers aboard, including the railroad’s president and directors, the president of the James River and Kanawha Canal, the local mayor, councilmen, bank president, and press. By 11:00 the train had reached Big Springs, a distance of seventy-five miles. The cars had been manufactured in Lynchburg, the locomotives at Richmond’s Tredegar Iron Works; a Lynchburg reporter noted proudly that both manufacturers were known “alike for power and beauty of workmanship.” Also praiseworthy, according to this account, was the way in which the railroad had conquered nature and geography. The railroad crossed the Blue Ridge at Bedford’s Gap, where the grading was so smooth that passengers were “entirely unconscious” of the elevation to which they were carried. On arrival at Big Springs, the passengers were treated to “an abundant and excellent repast” in the town depot, courtesy of the railroad.12

While the Railroad boom of the 1850s excited Virginians’ imagination, it also raised expectations and aggravated intrastate sectional differences. A tone of desperation characterized many of the requests for public subsidies, most of which could not be supported. Those frustrated blamed undue political influence. The General Assembly had “long pursued a policy which frittered away the resources of the State on local improvements designed to produce no grand result,” declared a group of Piedmont petitioners in 1851, but only to “subserve the purpose of individuals or sections, and having no concentrated or concerted result in view.” The protests of the Northwest in particular grew bitter during the 1850s. Some of the bitterness reflected, as it did in other parts of the commonwealth, acute competition between towns. Just as Petersburg blocked competition from Hampton Roads, Wheeling sought to maintain its near monopoly over the trade of ...