![]()

1: Is There Reason for Hope?

The Second Vatican Council and Catholic Interreligious Relations

Leo D. Lefebure

Prelude

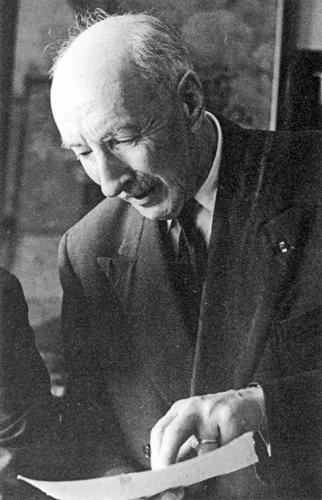

On June 13, 1960, two aging men, both octogenarians, meet in the Vatican: Jules Isaac is a French Jewish historian who has lost many of his family, including his wife and his daughter, in the Shoah and who has studied the history of Catholic attitudes toward Jews and Judaism; he has requested an audience with Pope John XXIII, who as a wartime papal diplomat in Istanbul had helped Jews in southeastern Europe to obtain transit visas to escape the Nazis and who recently as pope has called for a second ecumenical council to convene in the Vatican.1 Isaac expresses the tremendous hopes of the Jewish people regarding Pope John: “If we expect still more, what is responsible for that, if not the great ‘goodness of the Pope’?”2 Isaac requests that the upcoming ecumenical council correct the false and unjust statements about Israel and the Jewish people in traditional Catholic teaching. In particular, he mentions the traditional Catholic view that God punished the Jews for the crucifixion of Jesus by scattering them among the nations. The Jewish historian knows Catholic teaching quite well; to support his case, he cites the Roman Catechism issued in 1566 after the Council of Trent, which taught that Jesus died for the sins of all humans. Isaac proposes that this official teaching of the Catholic Church contradicts the widespread claim that Jews are uniquely guilty of deicide, the attempted murder of God. At the end of the audience, Isaac poses the poignant question of whether there is reason to hope. Pope John replies: “You have reason for more than hope.”3

Neither Jules Isaac nor Pope John XXIII would live until October 1965 to see the promulgation of the Declaration on the Church’s Relation to Non-Christian Religions, often known by its opening Latin words as Nostra Aetate; but they are arguably the two most important individuals setting in motion the process that led to this document. Both men know that behind their encounter stretch centuries of Catholic animosity toward Jews, shaped by a hostile reading of the Bible.4 Isaac is convinced that Catholic-Jewish relations have been marred by false beliefs and perceptions on the part of Catholics; he hopes that a more accurate reading of the sources of the Catholic tradition can correct these errors and improve this relationship. Thus he prods Pope John and other Catholics to review their Bible and tradition with a more benign attitude toward Jews and Judaism.5

Jules Isaac (1877–1963), the author of The Teaching of Contempt: Christian Roots of Anti-Semitism (L’enseignement du mépris, 1962). Isaac’s meeting with Pope John XXIII in June 1960 helped shape Jewish-Catholic relations during and after the Council. From André Kaspi, Jules Isaac ou la passion de la vérité (Paris: Plon, 2002), 184. (Courtesy of André Kaspi)

The horrors of the Shoah during World War II had dramatically changed the context of Catholic relations with Jews, and Isaac was by no means alone in his concerns. Even though Nazism was profoundly anti-Christian, by 1960 many Catholics had come to view the long history of Catholic animosity toward Jews as a tragic, sinful legacy that required rejection.6 In 1960, both the Pontifical Biblical Institute in Rome and the Institute of Judaeo-Christian Studies of Seton Hall University in New Jersey sent petitions to the Central Preparatory Commission requesting that the upcoming ecumenical council condemn anti-Semitism and improve the Catholic Church’s relations to the Jewish people. Meanwhile, an international working group of priests and laypersons met in Apeldoorn, the Netherlands, in August 1960 and sent a detailed memorandum calling for a conciliar statement on the Catholic Church’s relationship to the Jewish people.7

A number of Catholics who came from a Jewish background played a pivotal role in transforming Catholic attitudes toward Jews and in preparing for the Second Vatican Council. Johannes M. Oesterreicher and Annie Kraus, both originally Jews who became Catholics, pioneered efforts against Catholic anti-Jewish attitudes in the years before the Council opened. Gregory Baum and Bruno Hussar, also converts to Catholicism from Jewish backgrounds, proved instrumental as well. But even earlier, since the 1840s, some Catholic converts, most of whom originally came from Jewish backgrounds, had labored against Catholic anti-Jewish attitudes. John Connelly asserts: “Without converts the Catholic Church would not have found a new language to speak to the Jews after the Holocaust. As such, the story of Nostra Aetate is an object lesson on the sources but also the limits of solidarity.”8

In fact, the problem was far broader than relations with Jews alone. The Catholic Church in 1960 inherited a history of conflicted and often violent relationships with virtually every other religious tradition on this planet. One of the most serious obstacles to interreligious relations was the long-standing position that the Catholic Church denied any right to religious liberty for non-Catholics, but insisted on religious liberty for Catholics when they were threatened. In his 1832 encyclical Mirari Vos, Pope Gregory XVI set the tone for Catholic interreligious attitudes through his condemnation of “indifferentism”: “This perverse opinion is spread on all sides by the fraud of the wicked who claim that it is possible to obtain the eternal salvation of the soul by the profession of any kind of religion, as long as morality is maintained.”9 In accord with this perspective, Pope Gregory condemned the notion of liberty of conscience in religion: “This shameful font of indifferentism gives rise to that absurd and erroneous proposition which claims that liberty of conscience must be maintained for everyone” [bold in online version].10 In 1960, this remained the teaching of the Catholic Church. The American Jesuit theologian John Courtney Murray had already advocated religious freedom, but the Holy See had ordered him to be silent on the issue.11

Catholic attitudes toward all other religions had historically been overwhelmingly hostile. Catholics traditionally viewed Muslims (who were named “Saracens” in official church statements)12 as forerunners and allies of the Antichrist and as associates of the Son of Destruction of 2 Thessalonians 2:3.13 Catholics often viewed Hindus and Buddhists as idolaters who bowed down before the graven images condemned in the Bible.14 There were, to be sure, Catholics who proposed more generous, respectful interpretations of other religions.15 In the nineteenth century, some Catholics believed that there had been a primordial revelation to the first humans and that this had left positive traces in various religious traditions.16 When the World Parliament of Religions was held at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, the leading American Catholic churchman of the day, James Cardinal Gibbons of Baltimore, participated and supported cordial interreligious relations, as did Chicago’s Archbishop Patrick Feehan.17 Yet the Apostolic Delegate in Washington, D.C., Archbishop Francesco Satolli, wrote a negative report on the Parliament of Religions to Rome, and Pope Leo XIII forbade Catholic participation in any future interreligious assemblies.18 In the early and middle twentieth century, a number of Catholics appreciatively explored other religions and developed friendly interreligious relationships.19 But in 1960, these more respectful and friendly voices had relatively little influence on the official Catholic magisterium. No Catholic ecumenical council in history had ever issued a positive statement about other religions.

After the audience with Jules Isaac, Pope John XXIII conferred with the Jesuit scripture scholar Augustin Cardinal Bea and at his recommendation directed the newly formed Secretariat for Promoting Christian Unity to develop a reflection on “the Jewish question” as part of the preparations for the Council.20 As soon as the news spread that the upcoming ecumenical council would consider making a statement on the relation of the Catholic Church to the Jewish people, intense and widespread controversy began; Arab governments were especially concerned that such a declaration would open the way for Catholic relations with the State of Israel.21 In response, both on the floor of the Second Vatican Council and outside, Cardinal Bea repeatedly insisted that the developing statement on relations with the Jewish people was a purely religious and theological document with no political ramifications.22 Yet many in the Middle East did not recognize any such distinction.

The Second Vatican Council was by far the most international ecumenical council in the history of the Catholic Church, with 2,600 delegates coming from 134 countries throughout the world. As the discussions developed, bishops from around the world pointed out that there were other religions than Judaism and urged the inclusion of other religious traditions in the prospective statement. Thus what began as a statement on “the Jewish question” attached to the schema on Christian ecumenism developed into a broader, independent declaration on the relation of the Catholic Church to all other religions.

Both before and during the Council, the discussions of a possible statement regarding other religions proved long, difficult, and controversial.23 At least three groups raised questions about the wisdom of a statement on other religions: (1) conservative Catholics such as Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, who rejected religious liberty and insisted that both Scripture and Catholic tradition had already judged the Jewish people and that no conciliar statement could change established Church teaching;24 (2) Arab governments, who lobbied strenuously against any statement that would exonerate the Jews from responsibility for the death of Jesus or recognize the legitimacy of the Jewish state; and (3) Christians from the Middle East who expressed a number of concerns from a variety of viewpoints. Jewish observers watched carefully as the discussions proceeded through various stages. When one of the drafts of the projected statement expressed hope for the eventual union of the Jewish people and the Catholic Church, Abraham Joshua Heschel, the leading Jewish theologian in the United States at that time, came to Rome and met with Pope Paul VI and other Catholic leaders; he expressed the apprehensions of the Jewish community that this statement implied the elimination of the Jewish people through conversion. It did not appear in the fina...