- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In this nuanced look at white working-class life and politics in twentieth-century America, Kenneth Durr takes readers into the neighborhoods, workplaces, and community institutions of blue-collar Baltimore in the decades after World War II.

Challenging notions that the “white backlash” of the 1960s and 1970s was driven by increasing race resentment, Durr details the rise of a working-class populism shaped by mistrust of the means and ends of postwar liberalism in the face of urban decline. Exploring the effects of desegregation, deindustrialization, recession, and the rise of urban crime, Durr shows how legitimate economic, social, and political grievances convinced white working-class Baltimoreans that they were threatened more by the actions of liberal policymakers than by the incursions of urban blacks.

While acknowledging the parochialism and racial exclusivity of white working-class life, Durr adopts an empathetic view of workers and their institutions. Behind the Backlash melds ethnic, labor, and political history to paint a rich portrait of urban life — and the sweeping social and economic changes that reshaped America’s cities and politics in the late twentieth century.

Challenging notions that the “white backlash” of the 1960s and 1970s was driven by increasing race resentment, Durr details the rise of a working-class populism shaped by mistrust of the means and ends of postwar liberalism in the face of urban decline. Exploring the effects of desegregation, deindustrialization, recession, and the rise of urban crime, Durr shows how legitimate economic, social, and political grievances convinced white working-class Baltimoreans that they were threatened more by the actions of liberal policymakers than by the incursions of urban blacks.

While acknowledging the parochialism and racial exclusivity of white working-class life, Durr adopts an empathetic view of workers and their institutions. Behind the Backlash melds ethnic, labor, and political history to paint a rich portrait of urban life — and the sweeping social and economic changes that reshaped America’s cities and politics in the late twentieth century.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Behind the Backlash by Kenneth D. Durr in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

A Contentious Coalition

In early 1944 John Cater submitted some verse written by coworkers at Baltimore’s booming Westinghouse defense plant to the Baltimore Evening Sun. The paper published the piece, even though Cater disavowed authorship. It was a good thing he did. “Beloved Baltimore, Maryland,” written from the point of view of the thousands of migrant defense workers who had flocked to the city for the duration, was a vitriolic attack on everything Baltimorean from its architecture—“your brick row houses should all be torn down”—to its economy. “You make us pay double for all you can sell,” the piece concluded, “but after the war you can all go to hell.” The Evening Sun received more than a thousand angry refutations. A postal worker dragged two bulging bags full of letters into the Sun Building’s lobby, reached into his pocket, and pulled out a contribution of his own. Weeks later “Beloved Baltimore” was still the most popular topic of conversation around town.1

This incident, characterized by Life magazine as “The Battle of Baltimore,” was less a fight between enemies than a quarrel between partners in a strained, but strong relationship. The coalescence of the New Deal coalition at large, a process also achieved amid the tumult of wartime, was equally contentious. Natives and newcomers, old-world ethnics and southern Protestants, all came into conflict but ultimately formed a political alliance under the Democratic umbrella. This rift between the New Deal coalition’s white working-class constituents was fleeting, but there was a much deeper divide between them and the blacks and middle-class liberals who were also integral to the New Deal Democratic coalition, one that was temporarily bridged but never closed during the war years and the four decades afterward.

The Great Depression laid the groundwork for the New Deal order, based on agreement among urban and rural working whites, blacks, and middle-class liberals that grassroots political activity and an activist state could create a more economically equitable society. But in Baltimore, it was not until World War II that a viable coalition came together. Among the uproar, overcrowding, inflation, and anger, key institutions took shape and fragile alliances were formed. Machine politicians began to respond more to ethnic and working-class concerns and less to old-stock business leaders, liberal political groups—chief among them the NAACP—flourished, and industrial unionism became entrenched in Baltimore’s workplaces.

This political transition was driven by three broader shifts. First, working-class Baltimore’s “new immigrants” of Eastern and Southern European heritage gained political influence that began to rival that exerted by German and Irish ethnics and native-stock whites. Second, Baltimore’s black working people, long restricted to unskilled, low-paid work, began to get better jobs—with and without government help. Finally, although many of the southern migrants who worked in Baltimore’s war plants returned home as quickly as possible, many more did not. Instead, southern whites stayed to become members of Baltimore’s postwar white working class.

The wartime boom made Baltimore, a relatively placid and culturally southern city, look more like a smoky, congested northern industrial city. Its politics also came to resemble that of other post-New Deal industrial cities. In presidential, state, and local politics a “New Deal” coalition of working-white, black, and liberal voters emerged, although each group understood the legacy of the New Deal differently. The most vocal of Baltimore’s grassroots New Deal activists, urban progressives, CIO-affiliated laborites, and black civil rights leaders considered the war a political opportunity. Their conception of “New Deal Democracy” included not only the extension of blue-collar workplace rights but also the expansion of rights for blacks in the community and on the job. For Baltimore’s white working people, however, the tumult of wartime was fraught with hazards. They welcomed the economic security that industrial unionism and wartime wages brought but resisted social initiatives that seemed to threaten the blue-collar community.

Economy and Society

Baltimore’s roots were in commerce rather than industry; as late as 1881 there were still only thirty-nine manufacturers in the city.2 By the turn of the century there were two hundred, but within a few years, as the nationwide tide of mergers swept the city, outside corporations bought up local firms and Baltimore became known as a “branch plant city.3 Nevertheless, by the late 1930s municipal leaders touted an “industrial community” closely resembling its northern counterparts.4 Iron and steel dominated the economy. Sparrows Point, owned by the Bethlehem Steel Corporation, was the city’s largest single employer, sprawling over two thousand acres where the Patapsco River met the Chesapeake Bay.5 Although the garment industry sweatshops downtown were closing fast, the textile industry remained Baltimore’s second largest employer in the 1930s. Mills built in Hampden, north of the city center, still produced cotton duck as they had for a century.6

Baltimore Harbor in 1939. (Courtesy of the Special Collections Department, Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore)

The transportation equipment industry was more robust. Bethlehem Steel had shipyards at Sparrows Point and along Key Highway in South Baltimore. Maryland Shipbuilding and Drydock was on the southern edge of the harbor.7 Glenn Martin, built in 1928 at Middle River, eleven miles northeast of downtown Baltimore, was quickly becoming the largest single airplane factory in the world. General Motors (GM) opened plants in South-east Baltimore in 1934.8 Electrical equipment manufacturers like Westinghouse and Locke Insulator contributed to the city’s industrial diversity. The largest of these was Western Electric, built in 1929 at Point Breeze, just inside the city limits on the northern edge of the bay.9

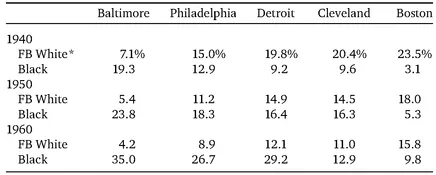

TABLE 1. Comparative Ethnic and Racial Composition by City, 1940-1960

Sources: U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1940 Census of Population, Characteristics of the Population: United States Summary (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1943), 1950 Census of Population, Characteristics of the Population: United States Summary (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1953), and 1960 Census of Population, Characteristics of the Population: United States Summary (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1963). * FB = Foreign-born.

Baltimore’s population was as diverse as its industry. A leading destination for nineteenth-century German immigrants, the city more closely resembled Cincinnati and St. Louis than predominantly Irish Boston or New Y 10 ork. These old-stock immigrants had to compete for jobs with blacks much earlier and on a greater scale than those in northern cities where the black populations were smaller. Dependence on the port for employment made these unskilled laborers especially vulnerable to market fluctuations, and in hard times native and immigrant workers exploited racial tensions to force blacks out of work and to protect their jobs.11

Baltimore had a southern segregationist inheritance that was, if anything, heightened by what one historian has called the “assertive self-consciousness” of its black populace, 90 percent of which was free before the Civil War.12 As Jim Crow descended on the border city, skirmishes between white and black labor heightened its effects, so that by the 1910s segregation was more pronounced in Maryland than in any other border state.13 Up to the 1890s, when an influx of black southern migrants began, there had been few exclusively black neighborhoods in the city. After the turn of the century blacks began leaving overcrowded and disease-infested alleys, displacing whites in upper west central Baltimore, and by 1910 half of the city’s blacks lived there. Whites petitioned the mayor to “take some measures to restrain the colored people from locating in a white community”; this resulted in a 1913 ordinance that made segregated housing legal in Baltimore. So effective was white Baltimore’s effort that it set precedent for legislation in other cities.14 This sanctioned black area, twenty-six blocks centered on Pennsylvania Avenue, became a booming black metropolis by the 1930s.15

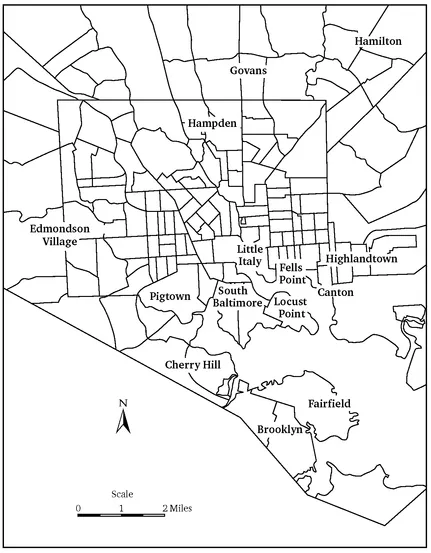

MAP 1. Baltimore neighborhoods

When Eastern and Southern European immigrants arrived at the turn of the century, ethnic working-class neighborhoods coalesced around the harbor. Outlying industrial suburbs included Brooklyn, on the southern edge of the harbor, and Sparrows Point, far to the east.16 Fells Point, Baltimore’s eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century shipping and shipbuilding center, occupied the northeastern edge of the harbor along with Canton.17 Up a gentle slope to the east was Highlandtown, a largely German community.18 Pigtown, in the near southwest, was named for its early packing houses. South Baltimore lay just below the city center, and to its east Locust Point jutted into the harbor.19 Only Hampden, home to Protestant textile mill-workers, was largely untouched by the new immigration.20

It was at Locust Point that the new immigrants disembarked. Some boarded the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and headed west. Others, especially the Poles, ferried across the Inner Harbor to Fells Point.21 A few got off the boat at the foot of Hull Street, walked a few blocks, and spent the rest of their lives in Locust Point.22 Over the next fifty years many of the Poles moved farther east into Canton and Highlandtown; others resettled in South Baltimore and Brooklyn.23 Italian immigrants gathered in a neighborhood on the near east side that became Baltimore’s “Little Italy” before gravitating west in later years.24 Czech, Lithuanian, Ukrainian, and Greek enclaves also took shape in South and East Baltimore.

The Catholic Church lay at the heart of these ethnic enclaves.25 The oldest parishes were Irish and German. A few remained that way, but others, like St. Leo’s, which became the center of Little Italy, adopted the nationality of its new congregation.26 The church served as a bulwark for both the existing social structure and the immigrant community. As these immigrants arrived, Baltimore’s James Cardinal Gibbons lauded Catholicism’s “tremendous power for conservatism, virtue and industry” among working people.27 In the 1920s and 1930s Baltimore’s Catholics shared Archbishop Michael Curley’s faith in the “Catholic Ghetto,” emphasizing self-sufficiency and disdaining secular individualism. Curley encouraged them to maintain their ethnic traditions and resist “forceful, improper Americanization.” 28

A building boom accompanied this influx of white ethnics, helped along by the institution of ground rent. Under this system, homes were bought and sold but landowners kept the “ground” and charged rent. This cut initial purchase costs, making housing more affordable for working-class people: Canton resident Bronislaw Wesolowski paid a mere $750 for his four-room row house in 1910.29 Of the forty thousand homes built in the 1880s and 1890s, most were the two-story, narrow red brick row houses that came to typify Baltimore’s working-class neighborhoods.30 White working-class Baltimore prospered in the 1920s. Home ownership rates rose, families bought radios, and a few could even afford cars. Social and political clubs multiplied and ethnic institutions flourished as working people enjoyed rising living standards.

MAP 2. Ethnic population, 1940 (Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1940...

Table of contents

- Table of Contents

- List of Tables

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- CHAPTER 1 - A Contentious Coalition

- CHAPTER 2 - Reds and Blue Bloods

- CHAPTER 3 - You Make Your Own Heaven

- CHAPTER 4 - The Right to Live in the Manner We Choose

- CHAPTER 5 - Spiro Agnew Country

- CHAPTER 6 - The Not-So-Silent Majority

- CHAPTER 7 - Making the Reagan Democrat

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography