![]()

Chapter One: Pueblos and Catholics in Protestant America

The high point of Zuni Pueblo’s annual round of ceremonies is the Shalako festival, held each year in late November or early December. The powerful beings who give the festival its name appear as giant birds, sometimes called the “Messengers of the Gods,” who carry the Zunis’ prayers for rain to all the corners of the earth. Members of the Zuni order of koyemshi, sacred clowns who are often called “mudheads” for their clay-brown masks, signal the impending arrival of the Shalako with announcements in the plaza. Meanwhile, the prayers and ritual purifications that make up the first stages of the ceremony are performed in seclusion in the kivas. Before the public festival begins, those who are to personate the Shalako go to a shrine outside the pueblo to plant feathered prayer sticks. There they put on their costumes— ten-foot white frame structures adorned with colorful blankets and a spread of eagle feathers above a blue face mask—and then process into town to begin the public festival. Their walk symbolically retraces the path of the ancestors as they journeyed from their place of emergence into this world, all the way to the Zunis’ home at the center of the earth. Eight houses are newly built or renovated each year for the festival. One is dedicated to each of the six Shalako, one to the koyemshi, and one to the “Council of the Gods,” an honored group of the ancestral deities known to the Zuni as koko, who return each year with gifts of rain and other blessings. The personators spend the night in these houses, performing chanted prayers and dances that they have spent the past year rehearsing.1

Zuni tradition holds that the successful completion of this and other ceremonies each year is necessary to ensure the well-being not only of the tribe but of the entire world. In a recent autobiography, the former Zuni tribal council member Virgil Wyaco provides a moving account of the Shalako festival and its contemporary significance. He describes how, after their all-night performances, the Shalako personators face the considerable physical and spiritual challenge of competing in foot races the next morning. They are so exhausted by this time, Wyaco explains, that “if a rule has been broken or their hearts are not ritually pure, they may fall. The old men think on these matters,” he writes, “and sometimes say that a disaster elsewhere in the world was caused by a Shalako falling.” According to traditional Zunis, the Shalako and other ceremonies literally maintain the balance of the earth and its seasons. As Wyaco puts it, “The dances must be every year if the Zuni world is to survive.” If not, then “we Zuni believe that the outside world, too, would cease to exist.”2 In December 1922 Zuni’s six chief priests defended their land and ceremonies against threats of disruption by articulating the same significance. These were the Pueblo’s “constant prayers for rain,” they explained, crucial for the life of the tribe and indeed for “all the people who exist in this world.” As the sixth priest concluded, “We the Principales agree to this matter, that this precious religion should never suffer harm.”3

The Shalako cross to south side of the river, Zuni Pueblo, 1897. Photo by Ben Wittick. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., neg. no. LC-USZ62-115456.

When he referred to Zuni tribal ceremonies by the English-language term “religion,” this priest—or his Zuni translator—was employing unusual terminology for Pueblo leaders in his or any previous era. During the Spanish colonial period, after initial suppression of Indian “paganism,” Franciscan missionaries and Pueblo Indians developed a mutual accommodation that recognized Catholicism as the Indians’ “religion” and minimized the appearance of conflict between Catholicism and indigenous practices. Shaped by that history, Pueblo leaders would initially contest American restrictions on their ceremonies by defining them not as religious practices but simply as a beneficial and integral part of Pueblo life. The Zunis may have been quicker to adopt the language of religion to describe and defend their indigenous ceremonies precisely because, unlike the other New Mexico Pueblos, they did not identify themselves as Catholics.

The Protestant reformers, missionaries, and government officials who dominated nineteenth-century U.S. Indian policy uniformly derided Indian traditions as “paganism.” Protestant leaders merged Christian traditions of religious comparison with anthropological theory to construct a hierarchy of religions with Protestant Christianity at the top. For them Indian “religion,” if it merited that designation at all, shared the same “degraded” qualities condemned in the Bible and shared by other “pagans” worldwide. True religion cultivated “civilized” standards of conduct and morality, understood in exclusively Anglo-Protestant terms, and made its adherents fit for American citizenship. In this sense, only Christianity—and often only Protestant Christianity—qualified. Indigenous traditions of any kind could be seen only as an impediment to the civilizing process. Convinced that civilization relied on the one true religion, Protestant leaders prescribed Christian missions as the most effective way to achieve the government’s civilizing goals.

Until the 1920s Roman Catholics represented the most significant threat to this virtual Protestant establishment in Indian affairs. Catholics had a far more significant history of missions among the Pueblos and many other Indian tribes than their Protestant counterparts, but they struggled for equal influence in the anti-Catholic environment of nineteenth-century America. Like most Pueblo leaders, Catholic missionaries defended against Protestant incursions by insisting that the religion of these Indians was Catholic. Forced to negotiate Protestant-Catholic conflicts, early twentieth-century government officials tried to establish religious neutrality on the reservations and in Indian schools. In effect, “religious liberty” for Indians in this era meant the freedom to choose between Protestant and Catholic religion. In this way, Catholic challenges to the Protestant establishment only intensified the exclusion of American Indian traditions from the category of religion. In such a context, it only made sense for most Pueblo Indians to continue their longtime strategy of defending their ceremonies as “customs” that did not interfere with their Catholic “religion.”

“Customs” and “Religion”: Pueblo Identity under Spanish Rule

Pueblo Indian stories of origin like that reenacted in the Zuni Shalako relate how the first ancestors emerged into this world from a series of previous worlds underneath this one. With the guidance of the spirits, they moved around from place to place until they settled at the very center of the earth where their descendants continue to make their homes. Archaeological research suggests that the group of tribes now known as the Pueblos developed through mixtures of the ancient peoples of the area. Ancestral Puebloans built the cliffside dwellings whose ruins are still visible around the Four Corners region of New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, and Colorado. Between 900 and 1200, they constructed the monumental Great Houses of Chaco Canyon, where they precisely aligned kivas and other architectural features to mark important solar and lunar events. When drought or other factors forced them to move south and east, they joined with other groups to build new towns and traditions. Around the beginning of the fourteenth century, the kachina cult of the ancestors (known at Zuni as koko) spread north from Mexico to the tribes of the Rio Grande Valley and then westward to the Zuni and Hopi. Starting in this period, warfare with the growing numbers of Athabaskan Indians moving into the area from the north forced villages to move and consolidate frequently, shaping the development of modern tribal identities. Today’s Pueblo Indians can be divided into six distinct linguistic-tribal groups: the Tiwa, Tewa, and Towa, all three in the Tanoan family; and the linguistically unrelated Keresan, Zuni, and Hopi (an Uto-Aztecan language). Each of the nineteen modern pueblos holds a distinctive annual round of ceremonies that include saint’s day festivals, summertime corn and harvest dances, deer and buffalo dances, and masked or unmasked kachina dances.4

Like other Native Americans, the Pueblo tribes have endured a long history of colonial conquest and violence, including repeated attacks on their ceremonial traditions. The Spanish explorer Coronado, in search of the fabled “Seven Cities of Cibola” and their treasures of gold, first encountered the Zuni and then the tribes to their east in 1539. It was not until half a century later that Juan de Oñate led an army from Mexico City to lay claim to the area. Oñate and his successors forced the local Indians to recognize their authority under the Spanish crown and the Catholic Church, often punishing them harshly for failures to provide tribute or for other infringements. Acoma Indians resisted these impositions by throwing several of Oñate’s men to their deaths from the top of the high mesa where their town (which vies for the title of the oldest continuously occupied settlement in North America) is situated. Oñate famously retaliated with an attack that killed many Acoma people and punished the survivors by amputating one foot from each adult man and sentencing the children to twenty years of enslavement. Over the next few years, Spanish soldiers forced the women and children of Acoma to carry stones and lumber long distances and up the steep trail to the mesatop to construct a mission church, which still stands as a landmark of Acoma’s historic pueblo. In an effort to co-opt native religious devotion, Franciscan missionaries placed this and other mission churches on top of indigenous shrines and kivas and permitted some native dances to celebrate the saint’s days. Pueblo people used this opening to preserve indigenous tradition. Today tour guides at Acoma tell visitors how their ancestors built the mission church by dimensions of their own choosing, so that unbeknownst to the friars the numbers four, seven, and twelve (each with sacred significance in indigenous Keresan tradition) are repeated in every feature of the building.5

Map of the Pueblos, 1937 (with population figures). Adapted from Elsie Clews Parsons, Pueblo Indian Religion, map 1. Courtesy University of Chicago Press.

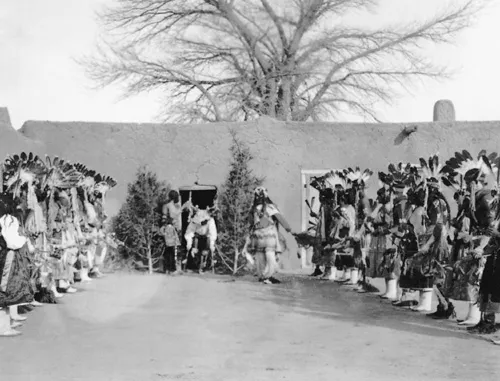

Corn dance, San Ildefonso Pueblo, 1924. Photo by M. W. Wyeth. Courtesy San Ildefonso Pueblo and Palace of the Governors (MNM/DCA), Santa Fe, New Mexico, neg. no. 172888.

By the mid-seventeenth century, the Franciscans had grown increasingly frustrated at the persistence of indigenous religious practices and reacted against the indifference of a provincial governor in the 1650s who openly accepted Pueblo ceremonies as harmless entertainment. They now insisted that all native ceremonies must be classified as the mortal sin of idolatry— implying false religion—which civil authorities in New Spain were obliged to persecute. Although Indians were legally exempt from the Inquisition, mission discipline was less predictable and potentially worse. Those caught practicing indigenous ceremonies could be severely whipped, imprisoned, enslaved, or even hanged. In the 1660s, Franciscans raided kivas and destroyed ritual items including altars, prayer feathers, and more than sixteen hundred kachina masks. In 1675 a new governor accused forty-seven Pueblo people of “sorcery”; four were condemned to death by hanging, and the rest were given lashings or prison sentences. Angered by such treatment, the Indians staged a successful revolt in 1680, which killed many Spaniards and destroyed most tangible symbols of Spanish rule. They particularly targeted the Franciscan priests, the mission churches, and the material items of Catholic ceremonial life. But the Indians struggled with drought and dissension after the revolt, and starting in 1692 Spain reconquered all except the Hopis.6

The Indians’ experiences under Spanish rule intensified their sense of common identity. In the colonial period, pueblo de indios (literally “Indian town”) did not refer exclusively to any particular Indians but was an administrative category used for any settled indigenous community under Spanish civil and ecclesial control. Not until the early nineteenth century, when the first Anglos arriving in the region misunderstood the Spanish word, did the term “Pueblo” gain ethnic connotations as a unifying designator for this specific group of tribes.7 By that time the Indians were ready to embrace this usage. Despite intermittent conflicts among the Pueblos, their history of joint resistance against Spanish oppression remained a unifying memory. By the late nineteenth century, the “Council of All the New Mexico Pueblos” met occasionally to address matters of common concern, and in 1922 this body—tracing its origins to the 1680 revolt—organized on a permanent basis to facilitate ongoing intertribal cooperation. (It has never included the Hopis, whose geographical distance and distinctive historical experiences have differentiated them from their counterparts in New Mexico.) Despite their many differences, the history and traditions shared by the Pueblos of New Mexico had in many respects forged them into a single people.8

After the reconquest of 1692, Catholicism increasingly became part of the identity and practice of most Pueblo tribes. Political turmoil, colonial oppression, and disease epidemics decimated Pueblo populations and resulted in new tribal consolidations. The Eastern Pueblos (the Tanoan and Keresan tribes of the Rio Grande Valley), especially those closest to the Spanish capital of Santa Fe, were forced to accommodate to the Spanish authorities and the religion they brought. Especially early in the eighteenth century, the open practice of indigenous ceremonies risked violent reprisals. Some of the more zealous Spanish governors sent soldiers to destroy kivas and ceremonial objects in the name of Christianity. Once again the people of these pueblos could not openly perform the masked kachina dances, which were condemned by the Spanish as demonic, but they continued to practice them without masks or in secret in the kivas. To compensate—or perhaps to create a public front for their own traditions—they gradually added Catholicism to their religious repertoire, reorienting their public ceremonial calendars around the Catholic holy days. Among most of the Eastern Pueblos, the Catholic patron saint’s day became the most visible public religious festival, and Holy Week and Christmas also came to be celebrated with indigenous ceremonial dances. The deer dance, traditionally held to thank the deer for its gifts of life, now also honored the birth of the Christ child.9

Those pueblos located furthest from Santa Fe were generally least affected by the centuries of Spanish colonial rule. The Hopis, whose mesatop towns in the modern state of Arizona placed them farthest west, completely resisted the Spanish reconquest. Hopi tribal leaders were so opposed to any Spanish influence that in 1700 they attacked and destroyed Awatovi, the one Hopi village that had invited the return of the Franciscan missionaries. Much to the Spaniards’ chagrin the Hopis gave refuge to other Pueblo people seeking escape from colonial oppression; a Tewa-speaking village founded by Indians who fled the Rio Grande region after the reconquest still thrives on one of the Hopi mesas. The Hopis and the Tewas they hosted never became even nominally Catholic, and their political and religious autonomy was not seriously challenged until the United States took over the region in the nineteenth century. Zuni Pueblo, although it was forced to accept the resumption of Spanish rule in 1692, was also located far to the west of Santa Fe and in practice remained largely self-governing. Zuni saw only occasional priestly visitors until the 1920s and remained minimally influenced by Catholicism until several decades later. For these reasons, Hopis and Zunis did not celebrate the patron saint’s days that became so important among the eastern pueblos, and the masked kachina and koko dances remained the central organizing principle of their ceremonial life.10

Deer dance, San Ildefonso Pueblo. Courtesy San Ildefonso Pueblo and Palace of the Governors (MNM/DCA), Santa Fe, New Mexico, neg. no. 135305.

Out of view of the Spaniards, the Eastern Pueblos also continued to practice far more of their indigenous traditions than their public festivals would suggest. To avoid the attention that might inspire repressive action, they barred outsiders from their environs for most ceremonies not linked to Catholic holy days. Such insistence on privacy for tribal ceremonies intensified and extended older pattern...