![]()

1 THE AMERICAN IDEA OF A CHURCH

Mormonism must first show that it satisfies the American idea of a church, and a system of religious faith, before it can demand of the nation the protection due to religion.

—Rev. A. S. Bailey, Christian Progress in Utah (1888)

On 20 January 1903, Utah’s predominantly Mormon legislature elected Reed Smoot to the U.S. Senate.1 A longtime leader in the local Republican Party, Smoot had hoped to run in 1900 but withdrew from the race on the advice of the presidents of his nation and church, leaving victory to wealthy miner and Catholic Thomas Kearns. By tacit agreement, Utah’s seats in Congress were shared equally by Mormon and non-Mormon citizens, and it was now the Mormons’ turn. Smoot convinced his church president to support his candidacy, though some of Smoot’s brethren were wary of the unwanted attention his election would invite to Utah’s already too-scrutinized politics. Smoot was, after all, not merely a prominent Republican; he was a very prominent Mormon, even an “apostle,” one of only fifteen men with plenary authority over the L.D.S. Church and in direct succession to its presidency.2 The prospect of a Mormon hierarch in the Senate was troubling to the new Republican administration, too. Senator Kearns carried the message home for the president. “‘This afternoon,’ he told the local press, ‘President Roosevelt requested me to state … that he desired to be placed on record as kindly but firmly advising against the election of any apostle to the United States Senator-ship.’”3

The concerns of both church and state leaders were validated when, six days after the election, the Salt Lake Ministerial Association petitioned the president and Congress to reject Smoot’s credentials. They protested that Smoot was part of an ecclesiastical conspiracy that impermissibly ruled Utah’s citizens and used its power to violate federal antipolygamy law, making Smoot a lawbreaker by association. The protest was drafted by the Reverend W. M. Paden, Princeton graduate and pastor of the First Presbyterian Church of Salt Lake City, with the editorial assistance of local attorney E. B. Critchow, law partner of the unsuccessful incumbent Joseph L. Rawlins. Already vulnerable as a lapsed Mormon and Democrat in an increasingly Republican state, Senator Rawlins had sealed his electoral fate by announcing on the Senate floor that Republican Kearns had earned his seat in a deal with the L.D.S. Church for “favors on the polygamy question.”4 Kearns responded by purchasing the Salt Lake Tribune, which had first made the charge against him. Later, when Kearns himself was deposed, he employed the paper to harass Smoot with the same allegation. Such conflation of Utah politics and commerce with religious creed was evidenced by other signers of the protest against Smoot’s election. The local Congregational pastor, the superintendent of Methodist missions, and the Episcopal bishop were joined by several mining superintendents, officers of various railroad companies, the former Tribune editor, and a federal chancery judge. Even the mayor of Salt Lake City added his name, though doing so indicated that the Latter-day Saints were not as much in control of Utah as even they would have liked to believe. In all, eighteen prominent clergy, business leaders, and public officials signed the petition against the new senator from Utah and called upon their co-religionists to support their cause.

Support was not long in coming. Petitions in opposition to Smoot poured into the Senate quickly. Some came from individuals; others, from orchestrated gatherings of concerned citizens. All were encouraged by Protestant para-church organizations and moral reform agencies. Neither did the churches themselves hesitate to act directly through their governing bodies. Within three months of Smoot’s election, salvos from two of America’s largest Protestant denominations were fired from opposite ends of the country. The General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church, meeting in Los Angeles, and the Baptist Home Mission Society, assembled in Buffalo, New York, passed resolutions in opposition to Smoot. The Presbyterians received their charge from assembly secretary Rev. Charles L. Thompson: “It [Mormonism] is not to be educated, not to be civilized, not to be reformed—it must be crushed.” Warning that “relentlessly it fastens its victims in its loathsome glue,” Thompson exhorted, “Beware the Octopus. There is one moment in which to seize it, says Victor Hugo. It is when it thrusts forth its head. It has done it. Its high priest claims a senator’s chair in Washington. Now is the time to strike. Perhaps to miss it now is to be lost.”5 In response to the furor, Smoot asked that it be remembered, “I was a Republican before I was an apostle.”6 But for Americans, such things were so hopelessly mixed in Utah that the only cure seemed to be to eradicate the source of the confusion, the Mormon church.

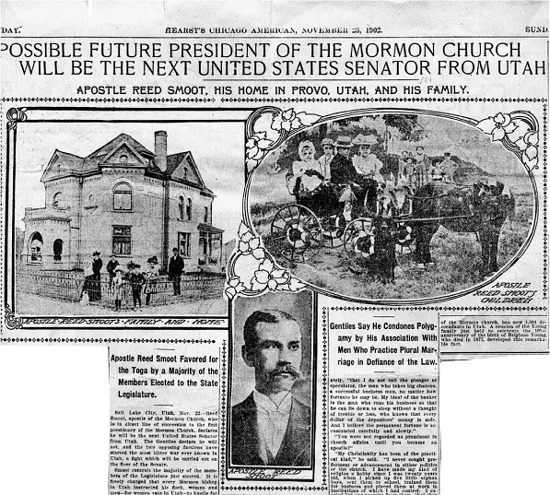

“Possible Future President of the Mormon Church,” Chicago Tribune, 23 November 1902. Smoot’s senatorial contest was national news. The Chicago Tribune’s coverage in this issue was typical in its stimulation of public fear of Mormon theocracy. Courtesy of L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Howard B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

Smoot was merely the opportune subject, not the true object, of the protestors’ campaign. In briefs filed with the Senate, the protestors took care to stipulate, “We accuse him of no offense cognizable by law.” Rather, they argued, Smoot’s ineligibility for office was based on his participation in a religious cabal that violated the law, corrupted the home, and controlled Utah’s government and economy at the expense of the nation. The senator-elect was, they said, “one of a self-perpetuating body of fifteen men who, constituting the ruling authorities of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, or ‘Mormon,’ claim … the right to … shape the belief and control the conduct of those under them in all matters whatsoever, civil and religious, temporal and spiritual, … encourage a belief in polygamy and polygamous cohabitation … [and]protect and honor those who with themselves violate the laws of the land and are guilty of practices destructive of the family and the home.”7 The protestors’ interests ran deeper than the rejection of Smoot from federal office, however. They hoped, in the words of one commentator, that “the Smoot case will abolish Mormonism without war. The scandalous blemish will be wiped out by the irresistible abrasion of the public intelligence, judgement, conscience and indignation.”8 Such overt intolerance, shocking to today’s sensibilities, was consistent with the times. Indeed, the adoption of means other than warfare to manage religious difference was an advance worthy of a Progressive Era.

Religious liberty did not come naturally to Americans. Rather, necessity mothered its invention and has directed its growth ever since. Freedom of conscience began as a “lively experiment” in the Puritans’ New World, but with strict limits, as the exiled Roger Williams and executed Mary Dyer could attest. Only gradually did the failure of any one church to dominate convert all churches to the principle of tolerance. Uniformity was simply impossible. As historian Sidney Mead observed, America’s colonial churches “seem to have placed their feet unwittingly on the road to religious freedom … not as the kind of cheerful givers their Lord is said to love, but grudgingly and of necessity.”9 For a century and a half after the Revolution, constitutional guarantees of religious freedom limited only the powers of the federal government.10 States were free to establish religion with state support, and they did so to varying degrees and over several decades. Not surprisingly, the descendants of the Puritans made Massachusetts the last to abandon formally the right to religious establishment. Even so, the staunchest religious defenders of religious liberty were not libertarians. The independent-minded Baptists, for example, agreed with the Congregationalists that non-Protestants should not be allowed full rights of citizenship. Thomas Curry’s indictment that both sects “adhered to Church-State arrangements that were co-extensive with their own theological, religious, and societal views” could apply to virtually all Americans in the early nineteenth century.11

“The Real Objection to Smoot,” Puck, 27 April 1904. As depicted in Puck magazine during the first year of the hearing, the L.D.S. Church’s priestly leadership and its assumed power over the new senator constituted the “real objection” to Smoot being received into the national legislature. The various charges against the church are labeled on the puppet master’s cloak. Courtesy of L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Howard B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

The extension of religious freedom to non-Protestants was early and often subject to the arbitrariness of majoritarian politics. Minorities who felt stifled or abused were encouraged to vote with their feet, as had the Mormons. Of course, indigenous religions, too, were expelled to the western frontier. Protestant homogeneity and hegemony were maintained by sending dangerous iconoclasts or other unwanted peoples out into the apparently limitless American frontier. By the late nineteenth century, however, it was no longer possible to believe that America was religiously homogeneous or able to safely consign its barbarians to the wilderness. Scientific advances in communications and transportation left everyone feeling the “centripetal tendency of the times” and the sense, if not the actuality, that “the frontier has gone.” It appeared that the nation’s interior was settled and its continental limits set, erasing the geographical buffer zones between religious antagonisms. Cities were filling the frontier, especially in the public’s imagination, and the cities themselves were being filled by increasingly diverse immigration and religious innovation.12

Moreover, by the turn of the twentieth century, no Protestant church could claim numerical dominance. America’s Catholic population had doubled, making it twice the size of the largest Protestant denomination. During the same period, America’s Jewish population quadrupled. The profile of the Protestant center had changed also. Methodists and Baptists outnumbered Presbyterians, Congregationalists, Episcopalians, and Lutherans. All Protestants were feeling the strains that would lead to the crisis over fundamentals in the 1920s. Meanwhile, the margins—comprised most obviously of Christian Scientists, Adventists, Mormons, and Holiness adherents—had not been evangelized into conformity, as traditional Protestants had hoped. Instead, new religious movements were growing through their own proselytizing efforts. Though mainstream churches still dominated the cultural center, they were losing their exclusive hold, and the margins were pressing noticeably toward the middle.13 This was nowhere more apparent than in Utah, where the homogeneous Latter-day Saints had turned the tables and ruled at the expense of a Protestant minority.

Senator Smoot represented not only Utah but Mormon rule brought to the national legislature. His arrival in Washington was a very public signal that freedom to be religious could no longer mean freedom to be one of the varieties of Protestantism. The public response to his election invited, even necessitated, reconsideration of the meaning of religious liberty in an America that could no longer be considered a Protestant nation demographically or expect to rid itself of religious iconoclasts through westward movement. Only hindsight allows one to say this with confidence, however. For those engaged in the Smoot hearing, it was a call-to-arms in defense of Christian America. As the Reverend Mr. Thompson warned the Presbyterian leadership, “Now is the time to strike. Perhaps to miss it now is to be lost.”

The Smoot hearing represented the last of several failed efforts to rid the nation of the Mormon Problem. From the church’s earliest beginnings, mobs had catalyzed its movement from New York to Ohio and then to Missouri. There, too, religious antagonism and fears of Mormon control over land and politics led to violence. The governor of Missouri considered the Mormons such a threat that he issued an extermination order against them in 1838 and drove them from the state with his militia. Subsequently, Illinois officials took actions that precipitated the murder of church founder Joseph Smith in 1844 and the expulsion of his followers, once again by local mobs. Illinois had its side of the story, however. In 1860, U.S. Representative John Alexander McClernand explained that the Mormons were expelled from his state “because they were unwilling to submit to the laws; because, in an attempt to trample the authority of the State under foot, they were overcome. Their maxim then was, and still is, rule or ruin.”14

Whatever his prejudices might have been, the congressman was not paranoid. The Mormons were radically separatist and triumphalist. They believed that God had rejected all other churches and had called Joseph Smith to institute a new dispensation of the Christian gospel, even “the fullness of times,” when all knowledge and every power that had ever been revealed would be restored in their day, the last days preceding Christ’s return. Thus they named themselves “The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.” Capitalization of “the” was intentional and meant to be instructive. Though they had their beginnings in the evangelically “burned over” region of New York, the people who arrived in the Rockies in 1847 had parted philosophical company with seekers of primitive Christianity.15 Sm...