![]()

Chapter One: Secret Sites

Black Washington, D.C., and Howard University

A quick glance at any history of the black experience in Washington, D.C., through the end of World War II reveals that it was exclusively black. The wall of segregation that had begun to crumble during Reconstruction was reinforced at the turn of the century and then completely restored during Woodrow Wilson’s presidency. Although it is difficult to argue that the District was ever truly integrated, segregation did not become government policy until Wilson arrived in Washington accompanied by a powerful cohort of southern congressmen who had pledged their support of white supremacy. Under Wilson’s administration, black and white employees were isolated from each other in the Bureau of Engraving cafeteria, and separate bathrooms were installed in the Treasury Department.1 With housing segregation already largely in place, Wilson’s employment policies simply reinforced the bifurcation of Washington into a white urban area and an interior black enclave, or what white historian Constance Green called the “secret city.”2

Constraining as this new and pervasive segregation may have been, certain segments of the District’s black population were able to thrive. Though we can consider New York City and Chicago to have been the cultural centers of black America, Washington was black America’s intellectual center from the end of the nineteenth century to at least the end of World War II. The seat of black intellectual activity in the District was Howard University.

Howard and its surrounding neighborhoods were where Abram Harris, E. Franklin Frazier, and Ralph Bunche practiced their craft. Just as New York City’s political, literary, and artistic worlds molded the famous “New York intellectuals,” Washington’s social, cultural, and political rhythms duly affected the Howard intelligentsia.3 The discriminatory racial policies and intraracial class conflict of the District of Columbia shaped the daily experiences of the Howard group. At the same time, segregation created social and economic possibilities within black Washington that facilitated the excellence of Howard University and the liveliness of related institutions. The upsurge in black progressive political activism in the District during the New Deal depended largely on the haven Howard provided for intellectual independence. Given this fact, it is ironic that radical critiques of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal programs came from an institution whose existence depended on the federal government. Furthermore, it is ironic that an all-black institution protected the anti-racialist and class-based arguments that Harris, Frazier, and Bunche advanced during this era. That this institution was located in the middle of an all-black residential and commercial enclave that was highly stratified in class terms and that historically had been politically conservative or quiescent, makes this history all the more remarkable.

Black Washington may have been generally confined to a certain geographic space within the District,4 but that did not mean the community was of one soul or one thought. Black wealth and poverty shared the same spaces—the former in large row houses, the latter in the alleyways. All together, aristocrats, politicians, store owners, professionals, domestic workers, students, and professors made their homes in the neighborhoods around Howard. A broad social history of black Washington and Howard reveals the complexity of the secret city. Through an investigation of a variety of secret sites—social life, Howard University, community activism, faculty and student activism, and the events leading to the establishment of the National Negro Congress—it becomes clear how the socioeconomic politics of the New Deal became intertwined with daily life in black Washington. During these years, Howard University emerged as a nexus for political and intellectual activity as Abram Harris, E. Franklin Frazier, and Ralph Bunche articulated a class-based critique of race politics and leadership in the 1930s.

Table 1 Composition of the Population of the District of Columbia, 1930

Total population | 486,869 |

Native white | 323,982 |

Foreign-born white | 29,932 |

Black | 132,068 |

Percent native white | 66.5 |

Percent foreign-born white | 6.1 |

Percent black | 27.1 |

Source: Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930. Population, vol. 3 (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1932), 383–92.

The Social Milieux

Decades before Mordecai Johnson, Howard University’s first black president, arrived in 1926 and aggressively moved to turn the school into a modern university, black Americans throughout the country regarded Washington as an active intellectual, social, and cultural center.5 Although the city’s appeal dimmed somewhat with the rise of the discriminatory practices that accompanied Wilson’s administration, longtime residents still felt great pride in what Washington represented for black Americans. May Miller Sullivan, a descendant of an old and established Washington family (her father was Howard scholar Kelly Miller), put it plainly: “People talk about the New York Renaissance. Well, we didn’t have to have a renaissance.”6

With this attitude pervasive among the Washington elite and with the District’s wealth of institutional support of cultural and social activities, Howard University thrived. It was easy, for example, to attract top-rank black faculty and administrators to the institution. As far as black scholars were concerned, only Fisk and Atlanta Universities competed academically with Howard. But even though all three schools enjoyed the support of philanthropic foundations, only Howard received any notable support from the federal government. More often than not, this support (and the imprimatur that came along with it) greatly enhanced the quality of life on campus. No black school could compete with Howard when it came to the size of its endowment, the condition of the physical plant, faculty salaries, student body size, and the breadth of department specialization.7 Finally, if one were uneasy about living in the deep South and yet wanted to teach at a university, working at Howard and living in Washington may have been the only practical choice. The fact that the school became known as the “capstone of Negro education,” then, is not just a reflection of the faculty, students, and administrators, but also of the social realities of the time.

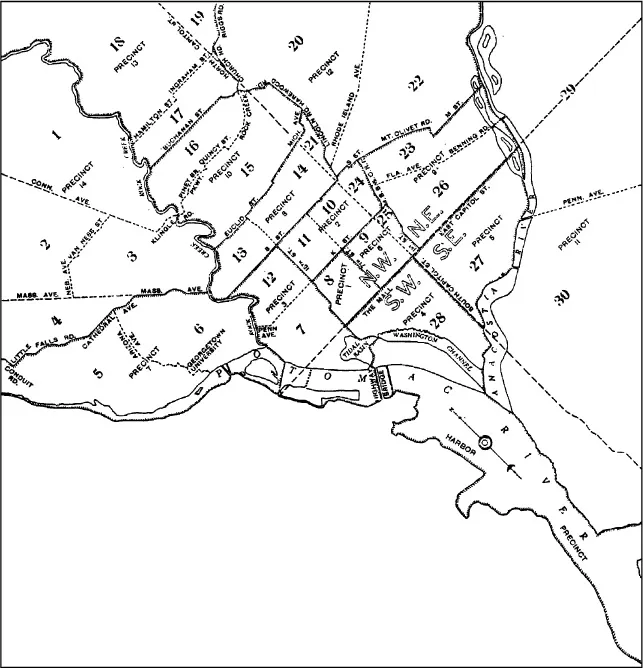

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

(Large figures on map indicate tracts)

United States Census tract map of Washington, D.C., 1930

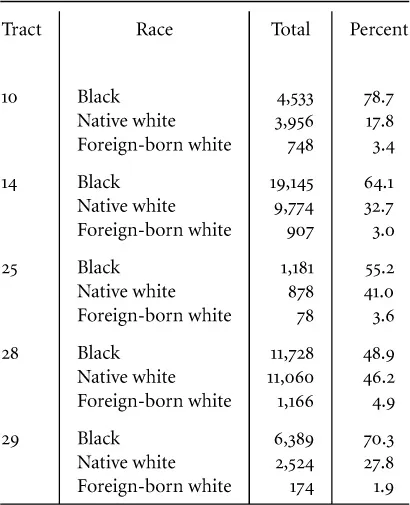

Table 2 Composition of the Population of the District of Columbia, by Tracts, 1930 (Only those tracts where blacks are the simple majority are listed.)

Source: Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930. Population, vol. 3. (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1932), 383–92.

Notes: Blacks account for more than 27.1% of the population (their District-wide percentage) in tracts 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 24, 25, 28, and 29. Blacks account for more than 10% of the population in tracts 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, and 30. Howard University and the U Street District are located in tract 14.

While far from perfect, the District developed a rich environment that was relatively hospitable to those of independent means. A fair portion of the District’s black community, for example, amassed sizable financial holdings and held considerable influence as the race’s political representatives in Washington. Southern politicians Blanche K. Bruce and P. B. S. Pinchback made their homes in Washington, as did the great Frederick Douglass. Federal jurist Robert H. Terrell exercised power both from the bench and as patriarch of one of the area’s most prominent black families. Civil rights advocates Archibald and Frances Grimké resided in the city and played a significant role in shaping the fabric of District black elite life. Anna Julia Cooper, writer, public school administrator, and educator, also thrived in Washington despite having to wage battles against gender bias and age discrimination.

Intellectual and cultural societies abounded in Washington. Alexander Crummell founded the American Negro Academy in 1897, and while this may have been the most intellectual and exclusive literary organization in the city, it was not the first. The Bethel Literary and Historical Association had been in place for nearly twenty years when the ANA was established.8 Other, less literary, societies flourished in the area. Some of these groups, such as the Bands of Mercy or the Little Defenders, were explicitly concerned with the economic, intellectual, and moral uplift of the lower classes. Meanwhile, organizations like the Association of Oldest Inhabitants were intended to validate status and class differentiation within the black community—a social construction that helped the elite hold on to the belief that there must have been some mobility or progress during this age of rigid segregation.9 Churches undoubtedly played a significant role in the black community, but the secret societies, clubs, and lodges filled in a gap left by the churches. Surely if the churches had been sufficient, there would have been little need as far back as 1900 for nearly forty benefit and secret societies and labor organizations.10

The segregation that defined club life in Washington was present in the school system as well. However, a lack of professional opportunities outside the District for talented teachers and a quasi-independent school administration combined to make Washington’s black public school system the finest in the country. Black District school board members (blacks had three seats on the nine-member board) fought to have their schools funded equally with the whites’, and faculties and administrators endeavored to create academic programs that were better than, not merely equal to, those found in the District’s white schools.11

The crown jewel of this system was Paul Laurence Dunbar High School. Founded in 1870 as the first public high school for blacks in the United States, Dunbar’s roots extended back to early Reconstruction Washington.12 By the 1890s, Dunbar (then M Street High School) was already known for its outstanding faculty and its record of accomplishment in preparing its students for advanced study.13 Indeed, over the school’s eighty-five-years, most of Dunbar’s graduates attended college, and this was in an era when the majority of Americans—white and black—did not even go to high school.14 College admission officers recognized the excellence of the Dunbar program, and as a result, it was one of only a few black high schools in the country whose students did not have to take a special competency exam to gain admission to college. In fact, students had to take an entrance exam in order to be admitted to Dunbar.15

Students who did not pass the Dunbar exam had no choice but to attend the other black high school in the District, General Samuel Chapman Armstrong Technical High School.16 The differences between Dunbar and Armstrong were vast. Whereas Dunbar saw itself as training the next generation of the talented tenth, Armstrong developed a curriculum based on vocational training and business. Fittingly, when Armstrong High School, named for the white founder of Virginia’s Hampton Institute, opened its doors in 1902, Booker T. Washington was its inaugural speaker.17

Considering how closely the two schools’ missions paralleled the famous debates between W. E. B. Du Bois and Washington, it should come as no surprise that the faculty and students of the two schools were fierce rivals.18 In a very real sense, the class differences that permeated Washington’s black club life were reinforced by the schools as well. Unfortunately, what could have been a leveling force only served to solidify black Washington’s class structure.19

Throughout the early 1900s, educators formed the core of black Washington’s stable middle class.20 Their jobs came through the city government, and thus they were afforded a job security virtually unheard of for black Americans at the time. Educated single black women particularly benefited from the opportunities available in the schools. Teaching was publicly acceptable, and it paid almost triple what the highest-paid black domestics received.21 Whereas the city’s educators were looked up to as the “economic mainstay” of the community, there were other opportunities available outside the school system. As far back as 1900, for instance, the number of black teachers, clergy, and physicians outstripped those of both New York City and Chicago.22

The black middle and upper classes were centered almost exclusively in the areas around Howard University. Shaw, the U Street district, and Strivers’ Row lay directly to the south and west of Howard; and LeDroit Park, the toniest address for blacks befor...