- 420 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Slavery in North Carolina, 1748-1775

About this book

Michael Kay and Lorin Cary illuminate new aspects of slavery in colonial America by focusing on North Carolina, which has largely been ignored by scholars in favor of the more mature slave systems in the Chesapeake and South Carolina. Kay and Cary demonstrate that North Carolina’s fast-growing slave population, increasingly bound on large plantations, included many slaves born in Africa who continued to stress their African pasts to make sense of their new world. The authors illustrate this process by analyzing slave languages, naming practices, family structures, religion, and patterns of resistance.

Kay and Cary clearly demonstrate that slaveowners erected a Draconian code of criminal justice for slaves. This system played a central role in the masters' attempt to achieve legal, political, and physical hegemony over their slaves, but it impeded a coherent attempt at acculturation. In fact, say Kay and Cary, slaveowners often withheld white culture from slaves rather than work to convert them to it. As a result, slaves retained significant elements of their African heritage and therefore enjoyed a degree of cultural autonomy that freed them from reliance on a worldview and value system determined by whites.

Kay and Cary clearly demonstrate that slaveowners erected a Draconian code of criminal justice for slaves. This system played a central role in the masters' attempt to achieve legal, political, and physical hegemony over their slaves, but it impeded a coherent attempt at acculturation. In fact, say Kay and Cary, slaveowners often withheld white culture from slaves rather than work to convert them to it. As a result, slaves retained significant elements of their African heritage and therefore enjoyed a degree of cultural autonomy that freed them from reliance on a worldview and value system determined by whites.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Slavery in North Carolina, 1748-1775 by Marvin L. Michael Kay,Lorin Lee Cary in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1: Slavery in North Carolina, 1748–1775

Demography, Production, Commerce, and Labor

By 1750 each colony in the various regions of British North America had gone through comparable stages of development: the invasion and conquest of Native American peoples and their lands; the replacement of indigenous populations by rapidly increasing numbers of European Americans and, in many areas, enslaved African Americans; the attempts by whites to achieve sufficiency in foodstuffs and other material necessities and to develop a viable export trade. Nonetheless, the results varied sharply with the southern colonies closest to the mercantilist ideal of plantation economies, producing staples needed by the mother country and absorbing British-manufactured goods. But historians have correctly stressed that the South was not a monolithic region. Varying blends of staples and complementary crops and differing rhythms of the slave trade, demographic configurations of the black and white populations, and African continuums yielded distinctive economies and produced varied slave societies over time and in the different colonial regions from Maryland south to Georgia.1 Thus, colonial North Carolina contained fewer slaves and lacked as extensive a plantation economy and planter elite as did colonial Virginia and South Carolina.2

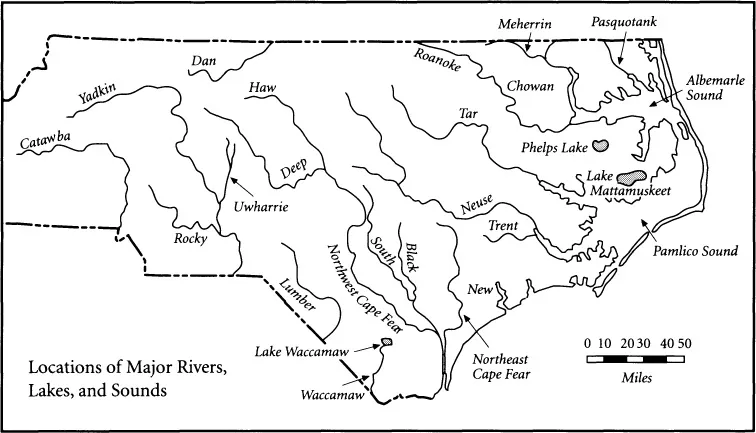

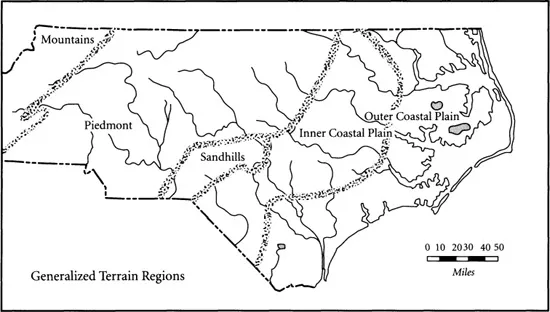

Partially responsible for North Carolina’s slower rate of economic growth were the significant natural handicaps the colony was burdened with. Nature carved a jagged, dangerous, shoal-burdened and constantly changing coastline whose treacherous Capes Hatteras, Lookout, and Fear claimed countless vessels. Although numerous rivers flowed toward the ocean, with one exception they emptied into shallow sounds rather than deep harbors. Only the Cape Fear River fed directly into the ocean, and it had shoals at its mouth (see Maps 2, 3). Such hazards added to the cost of transportation and insurance and had implications for both urban growth and the direction of trade.3

Overwhelmingly rural throughout the colonial era, like other southern colonies, North Carolina was also plagued initially by poor roads. A rudimentary system of north-south roads evolved in the coastal plain and piedmont regions, but the flow of rivers from northwest to southeast slowed the development of east-west routes. This hindered trade with the backcountry, retarded the expansion of port towns, and reinforced the tendency for much of the province’s early trade to flow southward to Charleston or north into Virginia and beyond. After 1750 the province made concerted efforts to develop overland links to meet the needs of the rapidly expanding backcountry. By the time of the Revolution, notwithstanding the persistent laments of travelers, roads in North Carolina compared favorably to those of other southern colonies. Improved transportation facilitated a rapid expansion of inland towns and aided the advance of such port towns as Edenton, New Bern, and Wilmington at the expense of others—Bath and Beaufort.4

The growth of this infrastructure both reflects and helps to explain why, by the late colonial period, North Carolina led all colonies in the production and export of naval stores and, having created a more diversified economy than other southern colonies, North Carolinia also came to export significant amounts of sawn lumber, shingles, barrel staves, Indian corn, wheat, livestock on the hoof, and meat and dairy products. Since perhaps more than one-half of the value of grain and livestock and a substantial proportion of the tobacco exports went overland to other colonies, and were thus counted there, it is impressive that the value of North Carolina’s officially recorded exports still surpassed those of New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New Jersey, and Georgia for the years just before the Revolution.5

These developments, in turn, interplayed with such diverse factors as the British mercantile system, population expansion, and the productive roles and services performed by those who toiled on, owned, and managed the colony’s farms, workshops, and commercial establishments. British bounties encouraged the production of certain goods, most notably naval stores. The province itself sought to encourage trade, with varying degrees of success, by improving roads, bridges, waterways, and harbors, regulating inns and ferries, establishing warehouses to store goods and to facilitate credit and trade, and inspecting commodities to ensure the quality of exports. Individual merchants also frequently played decisive roles in encouraging commercial farming and in shaping the colony’s trade. Usually clustered in the relatively small towns of North Carolina, and often agents of Scottish, English, or intercolonial mercantile houses, these merchants, together with local country store owners and itinerant traders, operated throughout the colony marketing local products while providing farmers with goods and credit.6

Map 2. Colonial North Carolina’s Major Waterways and Regions

Source: Harry Roy Merrens, Colonial North Carolina in the Eighteenth Century: A Study in Historical Geography (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1964), 20, 37.

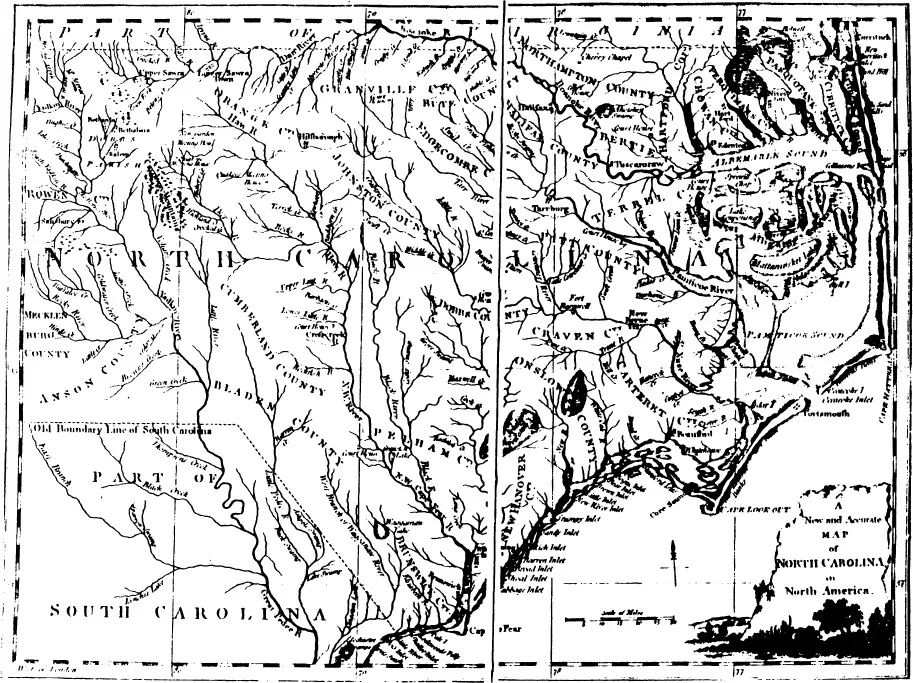

Map 3. Revolutionary North Carolina

Source: “A New and Accurate Map of North Carolina in North America,” first published in Universal Magazine (London: J. Hinton, 1779). (Map Collection, North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh)

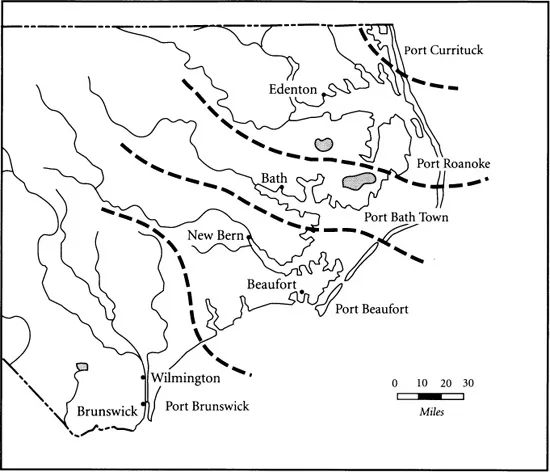

Map 4. The Ports of Colonial North Carolina

Source: Harry Roy Merrens, Colonial North Carolina in the Eighteenth Century: A Study in Historical Geography (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1964), 87. The assembly established customs districts, known as ports, in North Carolina early in the colonial period.

The process of European settlement and economic development began in North Carolina in the 1650s and 1660s, when the first white settlers entered the Albemarle region in the northeastern tip of the colony from Virginia. Assisted by their slaves, they prepared a variety of goods for export, among them tobacco, corn, wheat, and livestock products from cattle and hogs. This diversified farming, built on an extension southward of Virginia’s economy and supplemented by fishing and whaling, had little impact on urban growth or the development of ancillary industries in the region. Still, Edenton was incorporated in 1722, having come into existence a few years before this, slowly growing into a settlement of about sixty houses in 1730, North Carolina’s largest “urban center” at that time.

If North Carolina’s towns remained throughout the colonial years comparatively small, merchants and stores in these towns functioned to aid the development of commercial farming. Nevertheless, many of the Albemarle region’s exports, especially during the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, were hauled or driven overland to Virginia’s superior road and mercantile systems.7

Starting in the last decade of the seventeenth century, other white Virginians, some with their slaves, not only continued to move into the less-developed areas of the Albemarle region, but also went southward into the area watered by the Tar, Neuse, and Trent Rivers, all of which emptied into Pamlico Sound. By the early eighteenth century immigrants from France, Switzerland, and the Palatinate helped to swell the population of this Neuse-Pamlico region. Farmers first experimented with flax, hemp, and grapes, but, as in the Albemarle area, naval stores, wood products, Indian corn, provisions, livestock and its products, and tobacco came to be the mainstays of production. Limited urban settlements occurred even earlier in this area than in the Albemarle, with Bath chartered in 1706, Newbern in 1710, and Beaufort in 1715. Bath and Beaufort were ports of entry, or customs districts, but all three ports handled the forest and agricultural products of the area (see Map 4).8

Whites, chiefly from South Carolina, began to settle the Cape Fear region in the southeastern tip of the colony in the 1720s. Slaveowners, they brought with them a penchant, fostered by British inducements, for naval stores and lumber production. Starting in 1705 Britain had paid substantial bounties on colonial naval stores—£6 a ton on hemp, £4 a ton on tar and pitch, £3 a ton on turpentine and rosin, and £1 a ton on masts, yards, and bowsprits. Although in 1713 Parliament extended these bounties until 1725, complaints about poorly prepared resinous products led to their revocation and to the subsequent plunge of colonial exports of tar and pitch. In 1729, the same year that North Carolina became a royal colony, Parliament restored reduced bounties on pitch (£1) and tar (£2 4s.). This reintroduction of bounties could not halt a permanent relocation of the naval stores industry. Major South Carolina planters turned to rice and indigo, labor-intensive yet highly profitable crops, as their principal exports and shunted other economic activities to the periphery of the plantation section. Although some Cape Fear planters also became involved with rice and indigo starting in the 1730s, naval stores and lumber products remained preeminent.9

Given the aggressively commercial orientation of Cape Fear planters, their early stress on slavery, and their heavy concentration on naval stores and lumber—products that required the exploitation of large areas of land and extensive processing, marketing, transportation, and storage facilities—it is not surprising that the Cape Fear region developed the largest slave plantations in North Carolina, comparable in their use of slave labor to those in the South Carolina low country, and that two port towns emerged on the lower Cape Fear River to handle the region’s commerce. Although established in the early 1730s, eight years later than Brunswick (ca. 1725), Wilmington supplanted its neighbor because its location fifteen miles upstream at the confluence of the northwestern and northeastern branches of the Cape Fear River provided superior access to the interior. By 1754 Wilmington boasted seventy families to Brunswick’s twenty, and by the outbreak of the Revolution it had become, together with Edenton, the largest urban settlement in the colony. Its population of around one thousand, however, was still only one-third as large as that of Savannah, Georgia, and one-sixth as large as that of Norfolk, Virginia.

By the 1730s settlement began to spread westward into the interior from the Albemarle, Neuse-Pamlico, and, to a limited degree, Lower Cape Fear regions as well as from other colonies, especially Virginia. Population growth in the four interior regions of the colony was impressive. There, by 1755, whites and blacks equaled 42,353 persons, or slightly more than half of the colony’s total population of 83,945. The latter figure, in turn, amounted to a 48,000 person increase over the 30,000 whites and 6,000 blacks who lived in North Carolina in 1730—a per annum growth rate of 3.5 percent (see Tables 1.1–1.3).10

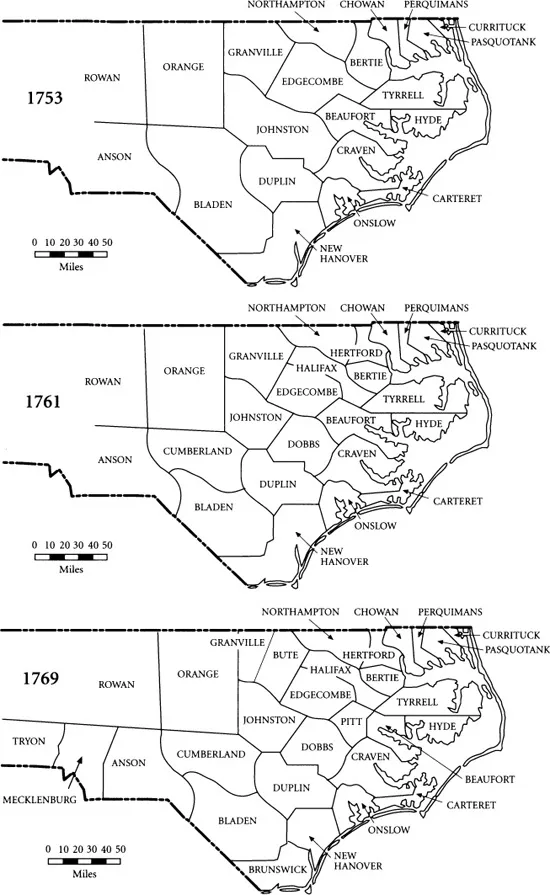

Despite this substantial population increase, the colony’s commercial infrastructure and entrepreneurial activity lagged behind population growth. Regional urban centers did not develop in the province’s newly populated and developing regions in the interior, and a poor east-west transportation system seems to have prevailed into the 1750s. Exports from the colony’s ports also reflect the limited capacity of the mercantile community during the first half of the eighteenth century to move goods from the interior to the coast. In 1736 the official exports of the province totaled about one-tenth of South Carolina’s. Despite the absence of other figures for the next two decades, the differential likely remained close to ten, for as late as 1768–72 it still equaled over six (see Table 1.9, Map 5).

Official records mask the colony’s heavy dependence on neighbors to market its products abroad. But whatever their deficiencies, the extant records do point to the diversity of the province’s exports, a characteristic that remained notable over time. In 1753, for instance, the colony shipped abroad about 100,000 pounds of tobacco, some 84,012 barrels of naval stores, and 62,000 bushels of corn, in addition to dairy products, beeswax, deerskins, peas, cattle hides, beef, and pork.11

The years after the onset of the French and Indian War witnessed an even more rapid surge of population than occurred from 1730 to 1755, changes that further reshaped North Carolina’s demographic contours and profoundly affected its economy. The yearly population growth rate during the twelve years after 1755 soared to a startling 5.4 percent. The population of whites jumped from 65,000 to 124,000 persons, while the population of blacks grew even more rapidly, from 19,000 to 41,000. After 1767 the rate of population growth probably slowed to a bit over 4 percent because of the emigration of disgruntled farmers following the Regulator defeat in 1771. Still, the colony’s population continued to mushroom, expanding about 40 percent to 230,000 during the eight years before the Revolution (Tables 1.1–1.3).12

All regions of the province grew rapidly after midcentury, but this occurred with heightened intensity as the population moved westward. In the Albemarle, Neuse–Pamlico, and Lower Cape Fear coastal regions, the total population rose by 29, 58, and 84 percent respectively between 1755 and 1767. In the interior Upper Cape Fear, Central Inner Plain–Piedmont, and Northern Inner Plain–Piedmont regions population totals jumped 125, 132, and 99 percent respectively. In the Western region, population soared by 229 percent (see Tables 1.1–1.2). The precipitous growth rates of the more westerly areas led to a significant redistribution in the colony’s population: the three coastal regions’ portion of North Carolina’s total population dropped from nearly half in 1755 to less than one-third in 1767 (see Tables 1.1–1.2).

Placing the focus of this demographic analysis on race and ethnicity, natural increase and, to a lesser degree, immigration more than doubled North Carolina’s white population to about 65,000 between 1730 and 1755, an annual growth rate of about 3 percent. Over the next twelve years the growth of the white population accelerated chiefly due to the increasing numbers of land-hungry settlers attracted to North Carolina from Virginia and other colonies to the north, especially Maryland and Pennsylvania. Streaming into the Northern Inner Plain–Piedmont and Western regions, they considerably outnumbered those migrating from North Carolina’s more easterly counties. Unlike most earlier migrants, a majority of these newcomers from other colonies were not English. Waves of Scots-Irish and German migrants took up land in Orange, Anson, Rowan, and Mecklenburg Counties and probably dominated the latter two most western counties. In addition, Highland Scots, primarily in the 1760s and 1770s, came directly from Scotland to help populate the Upper Cape Fear River counties of Bladen and Cumberland and to settle as far west as Anson County. White numbers for the entire colony during the years 1755–67 significantly reflect the demographic impact of these migrations—increasing at an annual rate of growth of about 5.1 percent and numbering about 124,000 in 1767, for a net gain of 89 percent since 1755 (see Tables 1.2–1.3). Despite the emigration of disillusioned Regulators, the number of whites by 1775 still climbed to around 161,000.13

Map 5. North Carolina Counties, 1753, 1761, and 1769

Source: Harry Roy Merrens, Colonial North Carolina in the Eighteenth Century: A Study in Historical Geography (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1964), 72–73.

If economic opportunity and land attracted most white migrants, it was the white need for labor that primarily exp...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Slavery in North Carolina, 1748–1775

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1: Slavery in North Carolina, 1748–1775: Demography, Production, Commerce, and Labor

- 2: Power and the Law of Slavery

- 3: The “Criminal Justice” System for Slaves

- 4: “Criminal” Resistance Patterns, I

- 5: “Criminal” Resistance Patterns, II: Slave Runaways

- 6: Slave Names and Languages

- 7: Marriage and the Family

- 8: Slave Religiosity

- Conclusion

- Appendix

- Notes

- Index