![]()

Part I

The Physical Entrepôt

![]()

1. The Environment

At the Gate of the Orient, sentinel stands Aden Majestic, o’er Araby’s sands.

TROOPER BLUEGUM, “The Home-Sick Anzac”

Sentinel to the East or the West—depending on one’s direction and point of view—Aden occupies a doubly strategic location: it stands in close proximity to the Bāb al-Mandab, the straits that command the flow of sea traffic between the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea, and straddles a most important juncture of north-south and east-west Indian Ocean trade routes. Yet even as it calls like a Siren to the commercially minded, the rocky peninsula on which Aden stands is far from idyllic. In the early 7th/13th century, Ibn al-Mujāwir, author of the most valuable account of the city in medieval times, pronounced the climate of Aden “stifling,” adding that “it turns wine sour within ten days.”1 In the 1880s and despite such modern amenities as automatic ventilation, a clearly disillusioned Arthur Rimbaud described Aden in his letters as “a horrible rock, without a single blade of grass or a drop of fresh water. . . . The heat is extreme, especially in June and September, which are the dog days here!”2

Even allowing a grain of salt for literary exaggeration and poetic idiosyncrasy, these reports hardly stray far from the truth: Aden’s rugged terrain, lack of fresh water, and notoriously harsh summer months, when even night temperatures rarely drop below eighty-five degrees Fahrenheit, are facts mentioned again and again in the literature on Aden, both ancient and modern.3 Such geographic “handicaps” would seem to undermine the place’s usefulness as a commercial entrepôt and even its suitability for the development of any urban center worthy of the name.

While different historical trajectories led to the flourishing of trade and society on Aden’s barren rocks in three different time periods, the three distinct cities—the ancient, the medieval, and the modern—were partly shaped by a common geography and climate. Moreover, the cities that flowered in these different historical moments share their geographic and climatic attributes with their shadowy forerunners and their obscure remnants. All of these settlements stood on the same rugged peninsula, were buffeted by the same set of winds, and were surrounded by the same luminous and beckoning sea.4 What are the characteristics of this constant, and how do local and regional geography and climate intersect with the historical processes and events in medieval Aden? To put it in Braudelian terms, this chapter examines the elements that define the longue durée of Aden’s history and highlights the ways in which these elements underlie the middle-range structures of Aden’s mercantile society and short-range events that took place in the city during the century and a half under consideration in this volume.

In the first three sections of this chapter, I discuss the three defining elements of Aden’s physical world—the sea, the “insular peninsula,” and water. I then analyze the relationship between the city and its immediate and farther hinterland. Individual settlements in Aden’s environs emerge as functional satellites to the port, while the less visible and perhaps more tenuous connection to the fertile Yemeni highlands proves to have been important for the subsistence of the maritime center’s nonagrarian population.

The Sea

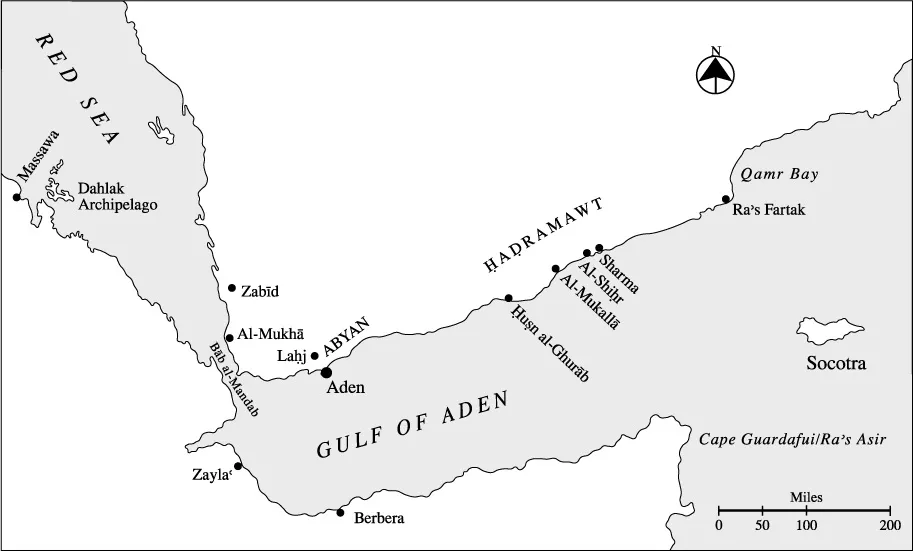

In telling the story of a city surrounded by sea, it is appropriate to start with precisely that sea, even as Braudel in telling the story of “une mer entre les terres” starts with the mountains, the plateaus, and the plains. The sea that washes the Aden peninsula also laps at the Horn of Africa (Cape Asir or Cape Guardafui) and at the gates of the Red Sea. It is the northwesternmost stretch of open Indian Ocean waters, and it is naturally named after Aden, its most important port. Like the Gulf of Oman, the Gulf of Aden resembles a funnel, narrowing westward toward the Bāb al-Mandab and opening widely eastward onto the Arabian Sea—so widely, in fact, that the dividing line between the two seas, which lies abreast of the Horn, where the Gulf of Aden is about two hundred miles wide, appears to be arbitrary.5

In terms of sea traffic and its control, the configuration of the Gulf of Aden means that the flow of ships converges—and is therefore easier to supervise or prey on—at its western end, in the general area of the Bāb al-Mandab. If proximity to the straits were the pivotal factor in harnessing the sea traffic, a site directly adjacent to the Bāb al-Mandab would have wrested the privilege from a place further away such as Aden. While not close enough to physically control traffic through the straits, however, the Aden peninsula lies advantageously near the mouth of the funnel, so that a maritime force, state, or group based there could exercise adequate command over regional waters. In addition, the spatially limited environment of the Gulf of Aden lends itself more readily to thorough navigational mastery by local mariners.

Map 2. The Gulf of Aden and the Southern Red Sea: Main Ports

Both documentary and literary sources from the medieval period testify to the city’s vested interest in the safe conduct of merchants, merchandise, and the ships that carried them. In their efforts to manage risk and mitigate damages, city officials and merchants took active measures to safeguard shipping against piracy and the elements; their efforts will be discussed in detail in part 2 of this book. Proximity to the city emerges as a critical factor in the implementation of such measures. Maritime patrols appear to have operated exclusively within the manageable maritime vicinity of Aden, while escort ships must have been most effective within the same maritime space. Furthermore, among all the instances of Indian Ocean shipwreck, the one documented case of a relatively successful marine salvage operation in the medieval period was sent forth from Aden and took place in the well-plied if treacherous waters near the Bāb al-Mandab.6

A watery realm easily within the city’s physical control played an important role in the success of maritime endeavors originating in the city. Maritime morphology and climate also contributed. Modern sailing directions for the area make special note of the absence of underwater hazards, reassuring mariners that “the Gulf of Aden is so clear of dangers that its safe and expeditious navigation depends mainly on a knowledge of the prevailing winds and currents.”7 Although local winds and currents were not to be overlooked, local knowledge and experienced seamanship could easily have handled these perils.8 Overall, the absence of treacherous shoals, shallows, and reefs in Aden’s immediate maritime foreland and the manageable local winds and currents meant that merchants operating from and through the city had fewer reasons to worry when expecting or sending forth a ship. In other words, by virtue of location alone, the port of Aden conferred a small measure of confidence on the generally unsafe business of shipping during the age of sail.

A comparison with the port of Alexandria, the great maritime port at the Mediterranean end of the India trade, demonstrates the true importance of the relative safety of Aden’s sea approaches. S. D. Goitein has shown that the most treacherous part of the voyage when shipping through Alexandria was in fact braving the coastal waves; the Geniza documents bear witness to several disasters occurring in the shadow of the Pharos.9 The great port of Jeddah on the Red Sea also suffers from very treacherous approaches, primarily as a result of offshore reefs and coral-encrusted coastal shallows. Even the accurate charts, gyroscopic compasses, radar, and depth sounders of modern times cannot always prevent disaster, as the visible relics of modern shipwrecks at the edges of the navigable channels of Jeddah Harbor testify.

If the sea was an open road to and from Aden, sailors had to reckon with the weather before any journey could begin. With its regular and marked seasonality, the monsoon system of winds and precipitation that prevails across the Indian Ocean significantly affects local and regional sailing patterns. Studies of seafaring practices in the medieval Mediterranean set in high relief the ways in which maritime seasons acted as the clock for littoral communities.10 Similarly, the Indian Ocean had a distinct maritime calendar based on the seasonal wind patterns, the winter northeastern and summer southwestern monsoons.11 In the Gulf of Aden, the local manifestations of the general monsoon system of the broader Indian Ocean region have important implications for the rhythms of port life.

Yemeni almanacs of the Rasulid period reflect the nexus of wind patterns and life in Aden by offering a remarkably intricate schedule for sailing to and from the city, defining seventeen discrete sailing periods through optimal times for travel between different harbors of the western Indian Ocean and the port of Aden.12 Such port-specific sailing seasons (mawāsim) also constitute a key concept in the technical Arabic literature on navigatio...