eBook - ePub

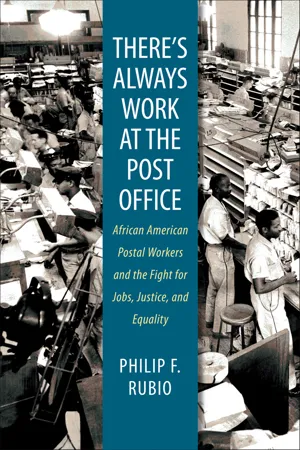

There's Always Work at the Post Office

African American Postal Workers and the Fight for Jobs, Justice, and Equality

- 472 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

There's Always Work at the Post Office

African American Postal Workers and the Fight for Jobs, Justice, and Equality

About this book

This book brings to life the important but neglected story of African American postal workers and the critical role they played in the U.S. labor and black freedom movements. Historian Philip Rubio, a former postal worker, integrates civil rights, labor, and left movement histories that too often are written as if they happened separately. Centered on New York City and Washington, D.C., the book chronicles a struggle of national significance through its examination of the post office, a workplace with facilities and unions serving every city and town in the United States.

Black postal workers — often college-educated military veterans — fought their way into postal positions and unions and became a critical force for social change. They combined black labor protest and civic traditions to construct a civil rights unionism at the post office. They were a major factor in the 1970 nationwide postal wildcat strike, which resulted in full collective bargaining rights for the major postal unions under the newly established U.S. Postal Service in 1971. In making the fight for equality primary, African American postal workers were influential in shaping today’s post office and postal unions.

Black postal workers — often college-educated military veterans — fought their way into postal positions and unions and became a critical force for social change. They combined black labor protest and civic traditions to construct a civil rights unionism at the post office. They were a major factor in the 1970 nationwide postal wildcat strike, which resulted in full collective bargaining rights for the major postal unions under the newly established U.S. Postal Service in 1971. In making the fight for equality primary, African American postal workers were influential in shaping today’s post office and postal unions.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access There's Always Work at the Post Office by Philip F. Rubio in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Labour & Industrial Relations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE WHO WORKED AT THE POST OFFICE (BEFORE 1940)?

William Harvey Carney ran away from slavery in Norfolk, Virginia, while still a teenager. Using the Underground Railroad in the early 1850s, he made his way to New Bedford, Massachusetts, less than twenty years after the famous black abolitionist Frederick Douglass arrived there in 1838 following his own escape from captivity in Maryland. (Carney’s father had also escaped, then bought his family’s freedom and moved them to New Bedford.) William Carney found work on the New Bedford docks where Douglass had earlier been denied work by white ship caulkers who threatened to strike if he was allowed to work. Both men had taught themselves to read while in slavery, and Carney was preparing himself for the ministry when the Civil War broke out in 1861. Blacks in Massachusetts began lining up to volunteer but were prevented from enlisting until after President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863, which he was compelled to issue, in part, due to battlefield losses, white soldiers’ desertions, and pressure from abolitionists like Douglass. (Douglass in fact helped organize the Union Army’s famous 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, with its all-black soldiers commanded by white officers.) There is evidence that Carney knew both Douglass and Douglass’s son Lewis. Carney and the younger Douglass both volunteered for the 54th, and Carney was the standard bearer for the regiment. Carney survived the disastrous assault on Ft. Wagner, South Carolina, with an injury, but managed to retrieve the U.S. flag dropped by the first standard bearer shot during combat. For this action Carney became the first African American to be awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for heroism in the Civil War—although not until 1900.

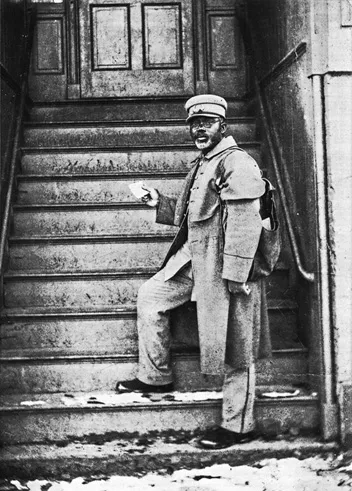

In 1869 Carney was still walking with a limp from his war wounds as he embarked on a career carrying mail for the U.S. Post Office in New Bedford (just a few months after James B. Christian was hired in Richmond, Virginia, making him the first known black letter carrier).1 Carney carried mail for thirty-two years. His name appears as founding vice president on the original

William H. Carney delivering mail in 1890 on his route in New Bedford, Massachusetts. A letter carrier for thirty-two years, Carney was also vice president of the New Bedford NALC Branch 18. During the Civil War, he was a sergeant and flag-bearer with the Union Army’s 54th Massachusetts Regiment, later becoming the first African American to receive the Congressional Medal of Honor. Note his Union Army greatcoat worn over his postal uniform. Courtesy of the Carl Cruz Collection, New Bedford Historical Society, Inc.

March 20, 1890, charter of New Bedford Branch 18 of the National Association of Letter Carriers (NALC), founded in 1889 at the Milwaukee annual meeting of Union Army veterans known as the Grand Army of the Republic.2

But there was not always work at the post office for African Americans like Carney and Christian. Opportunities for free waged labor for blacks at the post office only began officially in early 1865 as the Civil War was ending, with the Union military forces crushing the white supremacist slaveholding Confederacy.3 Black postal worker activism began at that time among Union Army veterans, former slaves, abolitionists, and free blacks from before the war, as blacks began working as “generation one” letter carriers, clerks, and postmasters. They were supported in those efforts by some white postal workers and government officials. But they also met much resistance from many others determined to keep the post office and its unions segregated. For the next eighty years, black postal workers—as individuals, in civic groups and unions, or within the predominantly white postal unions—led the fight for equality, combining civil rights unionism and grassroots militancy that would transform the post office and its unions.4

WHEN POSTAL WORK WAS WHITE ONLY

The post office “was the largest public enterprise in antebellum America,” notes economist Kelly Barton Olds.5 Olds’s study does not discuss black employment or black discrimination. But it does reveal the post office’s function as a patronage magnet: “By mid-century it employed 20,000 individuals.... In 1831, three-fourths of all civilian federal employees worked for the Post Office. By the time of the Civil War, this fraction had risen to almost fivesixths. Almost all of these employees were deputy postmasters or clerks.”6 And they were white without exception. In North of Slavery: The Negro in the Free States, 1790–1860 Leon Litwack mentions some of the earliest references I have found to black postal workers, tracing obstacles to black employment in the post office to before the Civil War.7 Litwack notes that before 1865 blacks were legally barred from working at the post office, although after 1828 enslaved blacks were occasionally allowed to handle mail under white supervision.8

What was the objection of whites to blacks working in the post office? It was born of the same fear that compelled the white slaveholding South to censor the mails and intercept antislavery tracts: concern for the security of the slave-holding states.9 Postmaster General Gideon Granger’s 1802 letter to a Senate committee chairman summed up white fears of blacks working for the post office, as Litwack summarized: “Negroes constituted a peril to the nation’s security, for employment in the postal service afforded them an opportunity to co-ordinate insurrectionary activities, mix with other people, and acquire subversive information and ideas. Indeed, in time they might even learn ‘that a man’s rights do not depend on his color’ and transmit such ideas to their brethren.”10 Granger’s anxiety was provoked by the successful rebellion of enslaved Africans in the French Caribbean colony of Saint-Domingue, which would become the free black republic of Haiti in 1804. Congress obliged Postmaster Granger by including in its 1802 law governing “Public law and Post-Roads” a section that proclaimed that “no other than a free white person shall be employed in carrying the mail of the United States,” making whites who violated that law subject to a fifty dollar fine.11 The subsequent 1810 post office law borrowed that section from the 1802 law practically verbatim.12 At that point, according to Litwack, Congress was excluding blacks from carrying the mail within a context of legislation restricting the rights of free blacks overall, but also within what he describes as a “sometimes conflicting and even chaotic federal approach.”13 Fifteen years later Congress shortened yet also broadened the provision to declare that “no other than a free white person shall be employed in conveying the mail,” while at the same time reducing the fine for white violators to twenty dollars.14

In 1828 Postmaster General John McLean allowed that black labor might be permitted to move mailbags from stagecoaches into post offices under white supervision.15 That same year also saw the election of Andrew Jackson as president and, with his administration, the inauguration of the spoils system in federal government service. In essence this was a form of “white affirmative action,” rewarding those who had helped in the preceding election to bring the Democratic Party to power, despite the effects on morale and performance when political affiliation of any kind superseded professional competence. Similar to the spoils system, both the 1810 and 1825 federal postal laws were constructed as restricting postal work to “free white persons only.” Their wording implied black exclusion in creating an exclusively white occupation, with whiteness serving as the basis for government service. It is significant that this was one of the first labor laws of the United States (if not the very first) and that it represented a fearful white elite reaction to the successful Haitian Revolution.16

ABOLITIONISTS IN AND OUT OF UNIFORM

“Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letters U.S.; let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder, and bullets in his pocket,” predicted black abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass in 1863, “and there is no power on the earth or under the earth which can deny that he has earned the right of citizenship in the United States.”17 There was a symbolic confluence of black men finally being allowed to bear arms for the Union Army in 1863 following President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation and the beginning of free city mail delivery throughout the United States. The end of the war saw many blacks, including Union Army veterans, begin to work at the post office. The Union Army uniform—like that of letter carriers—signified citizenship, manhood, and personhood in a country that had only a few years before denied that blacks had any “rights which the white man is bound to respect,” in the words of the infamous 1857 Supreme Court Dred Scottdecision.18

“Black men and women were routinely rejected for federal employment until 1861,” writes historian Jacqueline Jones, “when Boston’s William Cooper Nell received an appointment as a clerk with the United States Postal Service.”19 Cooper’s date of hire is actually listed in official post office records as 1863. But this still makes him the first known black postal worker appointed in the United States. (Individual post office records for this period do not indicate race or gender, forcing historians to use other means, such as newspapers and letters.)20 According to historian Dorothy Porter Wesley, Nell was an abolitionist whose activism led to his being appointed the first black postal clerk and government employee by white abolitionist Boston Postmaster John Gorham Palfrey, who in doing so defied federal Jim Crow postal law—with apparently no repercussions. Just a year before that appointment, Nell had been living in New York City helping to organize the fight against that state’s anti-black suffrage property qualification.21 While I have not found evidence of abolitionists targeting the exclusionary 1810 and 1825 post office employment laws, there is an indication of at least the beginnings of such a campaign the year following Nell’s appointment. In early 1862, Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner, an abolitionist and Republican, proposed legislation to allow blacks to carry the mail in Washington, D.C., only to see Representative Schuyler Colfax (R-Ind.) tie it up in committee, claiming there were no petitions or popular outcries for blacks to be admitted to the post office. (Later that spring, Nell would write to Sumner protesting post office prejudice.)22

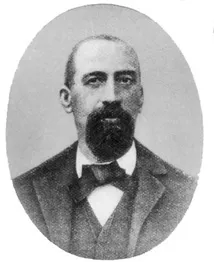

John W. Curry, probably in the fall of 1868, became the first known black postal worker appointed in Washington, D.C.—just three years after the white citizens of that city had voted 6,951 to 35 against black suffrage in a referendum.23 Only six years before, Washington had seen slavery banned by an act of Congress, with compensation being offered to slaveholders of up to $300 for each slave.24 Curry, like Nell, was a political activist for black public education, and joined the new D.C. Branch 142 (chartered in 1895) of the NALC—the first of today’s postal unions. Curry worked as a clerk, messenger, and sexton before spending most of his career as a letter carrier from 1870 until his death in 1899. Along with other newly appointed black postal workers, he owed his employment to a bill authored by Senator Sumner that passed on December 19, 1864, and was signed into law the same day as the one establishing the Freedmen’s Bureau, providing land and relief to former slaves—March 3, 1865—and forty years to the day of the last federal law restricting mail delivery to whites. The new law stated emphatically that “no person, by reason of color, shall be disqualified from employment in carrying the mails, and all acts and parts of acts establishing such disqualification, including especially the seventh section of the act of March 3, eighteen hundred and twenty-five, are hereby repealed.”25

John W. Curry, first known black postal worker hired in Washington, D.C., ca. 1870. Official records suggest he was first appointed in 1868 as a clerk, and then worked as a letter carrier from 1870 until his death in 1899. He was probably a charter member of NALC Branch 142, founded in 1895. Courtesy of Postal Record, National Association of Letter Carriers, AFL-CIO.

Many blacks and abolitionists joined the Union Army during the Civil War. Given the substantial rates of Union Army veteran entry into the post office generally, at least some of the first black postal workers were Union Army veterans, probably many of them postmasters.26 William Carney, along with William H. Dupree and James Trotter, were three prominent examples of early black Civil War veterans becoming postal employees. Dupree served with the 55th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment during the war, and afterward became manager of Station A in Boston’s South End.27 Trotter was a runaway slave from Mississippi who joined the black 55th Massachusetts Infantry regiment, and was one of its few black commissioned officers. In 1865, according to historian Stephen R. Fox, Trotter returned to Boston where he and other black war veterans received clerk appointments in the Boston post office.28

The experience of these and other early black postal workers suggests an absence of any substantial white postal worker resistance to black entry into the post office after the Civil War, compared to blacks’ experience in the private sector. In fact, white letter carriers in Newark, New Jersey (doubtlessly including members of another original NALC branch, Branch 38), in 1893 refused an invitation to ride in a local bicycle rally because their black coworker, Louis A. Sears, was denied entry despite having pioneered bicycle mail delivery in that city.29

William Carney was also just one among a growing number of black NALC officials. Scipio A. Jordan was the Arkansas state vice president, and the Little Rock Branch 35 corresponding secretary was Howard H. Gilkey. In Memphis, Tennessee, David W. Washington, probably the first black letter carrier in that city, was the first president of Branch 27, formed in 1889. Washington, described as a “substantial” citi...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- THERE’S ALWAYS WORK AT THE POST OFFICE

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- CONTENTS

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- PREFACE

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- ABBREVIATIONS

- CHRONOLOGY

- INTRODUCTION

- CHAPTER ONE WHO WORKED AT THE POST OFFICE (BEFORE 1940)?

- CHAPTER TWO FIGHTING JIM CROW AT HOME DURING WORLD WAR II (1940–1946)

- CHAPTER THREE BLACK-LED MOVEMENT IN THE EARLY COLD WAR (1946–1950)

- CHAPTER FOUR FIGHTING JIM CROW AND MCCARTHYISM (1947–1954)

- CHAPTER FIVE COLLAPSING JIM CROW POSTAL UNIONISM IN THE 1950S (1954–1960)

- CHAPTER SIX INTERESTING CONVERGENCES IN THE EARLY SIXTIES POST OFFICE (1960–1963)

- CHAPTER SEVEN BLACK WOMEN IN THE 1960S POST OFFICE AND POSTAL UNIONS (1960–1969)

- CHAPTER EIGHT CIVIL RIGHTS POSTAL UNIONISM (1963–1966)

- CHAPTER NINE PRELUDE TO A STRIKE (1966–1970)

- CHAPTER TEN THE GREAT POSTAL WILDCAT STRIKE OF 1970

- CHAPTER ELEVEN POST-STRIKE (1970–1971)

- EPILOGUE

- CONCLUSION

- NOTES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Index