![]()

1

Union Father, Rebel Son

WHEN NINETEEN-YEAR-OLD Henry Lane Stone joined the Confederate army, he did not just turn against the Union, or what he called the “cursed dominion of Yankeedom.” He also defied his family, especially his father. Stone’s parents were natives of Kentucky, but by 1861 they were living in southern Indiana with Henry and his four brothers. They were staunch Unionists, and at least one of Henry’s brothers volunteered for the Union army. But in August 1862 Henry, a middle child, felt drawn to fight for the Confederacy. Knowing that his family would try to stop him, he kept his decision secret and departed without even leaving a note. To make his way past Union pickets, he disguised himself as a poor farmer and headed for Kentucky to join the cavalry of John Hunt Morgan. A month later he revealed his whereabouts to his father: “Pap, I do not regret one practical my leaving home and every day convinces me I did right,” he explained, yet he realized the personal cost of his actions. “I can imagine how your feelings are, one son in the Northern and another in the Southern Army,” he acknowledged. “But so it is. . . . Good times will come again.” He signed the letter, “Your rebelling son, Henry.”1

Stone may have acknowledged that he was “rebelling” when he enlisted in the Confederate army, but he did not say why. Was he, like so many other Confederate soldiers, rebelling against the United States? Or was his a more personal rebellion against his family, especially his Union father? Or both? These questions vexed the Stone family and many other border-state families whose sons enlisted in the Confederate army despite their fathers’ Union sympathies. Their division, which mirrored the greater conflict between the long-established Union and the youthful Confederacy, earned the notice of newspapers for its startling frequency across the border states. Few families knew how to respond to their sons’ departure and spent the early war years trying to sort out the various meanings contained in the word “rebellion.”2

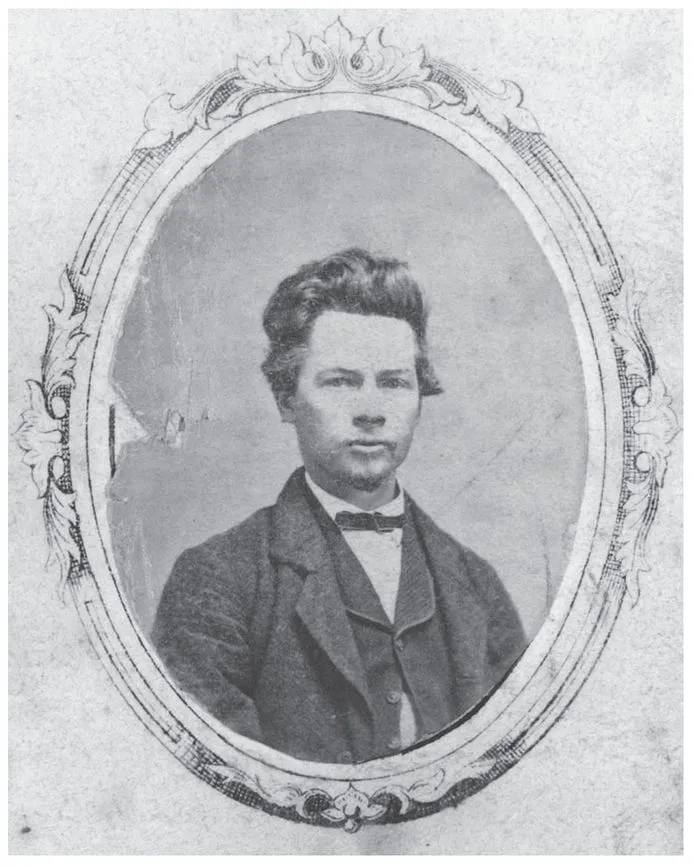

Portrait of Confederate soldier Henry Lane Stone taken in Kingsville, Canada,

January 1864, after his escape from the Union prison at Camp Douglas,

Illinois. Stone’s frequent letters to his Union family document his journey

back to the South later that year to rejoin his regiment for the duration of

the war. (Courtesy of the Filson Historical Society, Louisville, Ky.)

The personal papers of these border-state families offer few straightforward answers as to why their political allegiances settled along generational fault lines. These families were, like so many others in the border region, landowners who made their living by raising livestock and wheat. They generally lived in the low-lying areas and tended to own fewer than twenty slaves. They did not engage in the large-scale plantation agriculture of the Lower South but were still fairly wealthy, educated, and prominent in their communities. In most cases their nuclear families were intact, with mothers, stepmothers, sisters, and brothers sharing their households and generally working together on the family land. Yet when war came numerous sons, who averaged twenty-two years of age, enthusiastically left home to volunteer for the Confederate service, while their fathers remained Unionist advocates of compromise and moderation.

Fortunately these Union fathers and their rebel sons argued freely on paper during the war, explaining in vivid detail why they believed their loyalties were divided. Even though the sons who split from their fathers in most cases left their siblings and a mother too, it was conflict between father and son that inspired the most introspection. Male kin disagreed in particular about how personal their conflict was and to what extent the sons’ national loyalties were linked to or contingent on their loyalty to their fathers.

Rebellion

The brewing rebellion of the sons became apparent to border-state observers even before the fall of Fort Sumter. As early as February 1861, twenty-one-year-old Josie Underwood noticed that in her hometown of Bowling Green, Kentucky, “all the men . . . of any position or prominence whatever are Union men — and yet many of these men have wild reckless unthinking inexperienced sons who make so much noise about secession as to almost drown their fathers wiser council.” Border-state newspaper editors eventually took note of this family dynamic, including the Louisville Daily Journal, which months later declared the father-son conflict an “epidemic” and began writing lengthy essays on its pervasiveness.3

What these observers witnessed was the climax of a generational conflict that had been mounting throughout border-state society in the decade prior to 1861. During the secession crisis some of the most vigorous proponents of slavery and states’ rights were men born in the 1830s and 1840s. These were young adults who had never known a time without sectional conflict, who had lived through tenuous political compromises in Missouri and violent threats to slavery in “Bleeding Kansas” and in Harpers Ferry, Virginia. What they saw all around them was the elusiveness of a national consensus on slavery and a political landscape where division was the norm. In such an environment it was almost impossible not to take a vigorous stance on the issues of the day. These young border-state advocates of slavery and Southern rights, though not unique, developed a passionate enthusiasm for secession that set them apart from older generations and, in the cases considered here, from their own fathers.4

Their fathers, meanwhile, were fixtures of the border-state political establishment: among them were a Maryland governor, two Kentucky senators, and several congressmen. Most were either Whigs or, as the war approached, Constitutional Unionists and Democrats intent on forging compromises to stave off civil war. Their political affiliations generally reflected the ideological and geographic middle ground in which they lived, and it appears that most tried to impart that same moderation to their sons. “I would caution you against imbibing all the notions put forth by your advocates for slavery,” was how Samuel Halsey responded in 1857 to his son Joseph’s blustery antiabolitionist rant. To make his case, Samuel sent Joseph a “sensible tract” written by a Kentucky minister. Fathers like Halsey detected their sons’ radicalism early, but rather than demand outright conformity they generally permitted an open debate on sectional issues. Their letters reveal an energetic but tolerant exchange of ideas throughout the 1850s, as the fathers apparently believed that beneath their sons’ political vigor was a deeper agreement on national loyalty.5

By 1861, however, the letters of these fathers and sons took on a starkly different tone. Any political difference was no longer something as benign as words on a page; in wartime, it could mean opposing allegiances across a deadly battle. As war seemed imminent, fathers grew less tolerant of their sons’ independent political expression. They did not expect their sons to think exactly like themselves, but they did draw a line at specific actions. Service in the Confederate army was unacceptable. “Do not resign under any circumstances without consultation with me,” one Kentucky father demanded of his son, whom he feared would leave the U.S. Army for the South. Other fathers struck compromises, even promising to support their rebel sons financially if they did not volunteer for Confederate service. Still others, hopeful that the war would last only a few months, made their sons promise to stay at home for a year before enlisting in the Confederacy.6

Union newspapers challenged fathers to prevent their sons from leaving for the Confederacy and to compel them to join the Union forces. “If the young men are slow to enlist in the cause of human freedom,” advised the Louisville Daily Journal, “let the old men step forward, and by their patriotic example shame their degenerate sons and grandsons.” In this paper’s view, the mechanism of paternal authority was the most effective deterrent to a young man’s military support of the Confederate cause. After all, mid-nineteenth-century society considered it a father’s duty to nurture his son’s political allegiances. A mother might instill a general sense of civic duty and consciousness, but in matters of partisanship a father’s example was to be paramount. Fathers must live up to those expectations, the Journal exhorted, and most fathers did in demanding political obedience. Initially, many Confederate-minded sons complied, but over time they found complying with their fathers’ wishes intolerable. In the first year of the war the awkward promises of these sons set the stage for the “epidemic” lamented by the Journal.7

Twenty-three-year-old Matthew Page Andrews of Shepherdstown, Virginia (later West Virginia), promised his father Charles, a pro-Union Episcopal minister, that he would not volunteer for Confederate service and would remain in law school. But this became difficult for him when his classmates began to enlist. “My position is getting more and more embarrassing every day,” Matthew wrote his fiancée. “All the young men in town have joined one of the three companies formed here,” and they did not understand why Matthew failed to sign up. Peer pressure was severe; indeed, it had prompted many other young men to fight for the South. Yet Matthew vowed to remain out of the service because he did not want to “offend” his father. Meanwhile, Charles Andrews took the opportunity to reinforce his political authority in letters to his son. “I am much more calm than you are, & have a much more intelligent & impartial survey of the whole question,” he argued on one occasion and suggested that Matthew would come to share his opinions within weeks. Charles was overly confident, for Matthew never accepted his beliefs, although he did not volunteer for Confederate service.8

Sons like Matthew Andrews soon faced additional obstacles to obeying their fathers and retaining their civilian status. In 1862 and 1863 both the Union and Confederate governments passed conscription laws that compelled all men between the ages of eighteen and forty-five to serve in the military.9 This made it impossible to simply remain at home, since almost every young man had to enlist in the army supported by his state. For sons in the Union states of Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, and Missouri, the idea of being forced to join the Union army became an additional inducement to act on their Confederate sympathies and quickly head south. Henry Stone, who opened this chapter, explained to his father that while at home in a Union state he “was in great danger of being drafted where I could not have served.” After leaving in 1862 and joining the Confederate army, he wrote, “I’m contented.”10 Sons in the Confederate states of Virginia and Tennessee had the conscription laws on their side, which, in many cases, did encourage a son’s enlistment. But even in these regions some fathers stepped in to prevent the laws from affecting their sons. Matthew Andrews’s father, for example, used his connections to preempt conscription and to find his son a job in the paymaster’s office in Richmond, reasoning that a government job was less odious than service as a combatant against the Union.11

Other sons resorted to sneaking away from their fathers when it became too hard to resist the pressure of their peers or the law. The experience of twenty-year-old Ezekiel “Zeke” Clay was fairly common. Before the war, Zeke was schooled by several prominent Unionists. His family, in fact, offered a model of sectional compromise: his father, Brutus Clay, was a Whig member of the Kentucky legislature and a slaveholder, while his paternal uncle, Cassius Clay, was a vigorous abolitionist, and his distant cousin, Henry Clay, was the architect of several plans to prevent slavery from destroying the Union. On the other hand, Zeke had a significant circle of friends his age who attended pro-secession speeches and rallies and encouraged him to join them. His family knew of his dalliance with secession ideas but was openly tolerant of his views, even during the first months of the war. His stepmother, Ann, kept her own Union opinions to herself even while venting to her husband that Zeke talked about secession “like some one crazy.” Brutus maintained his silence, apparently confident that his son would uphold his agreement to stay home and manage the family land while Brutus served in the legislature.12

Over several weeks in September 1861, however, Zeke secretly plotted his departure. He approached a Confederate officer about obtaining a commission in the army, yet denied having done so when his stepmother heard rumors about the meeting. He also set about making gun cartridges to take with him — working deviously right under his stepmother’s nose — but claimed that they were for his father. Then one night the same month, after telling his stepmother that he was going loon hunting, Zeke rode off on his mare, taking along the blanket from his bed, one of his father’s rifles, and a small amount of clothing. In a note found in his bedroom, he explained his departure this way: “I leave for the army tonight. I do it for I believe I am doing right. I go of my own free will. If it turns out that I do wrong I beg forgiveness. Good bye. E.”13

Brutus Clay could hardly contain his anger when he learned what his son had done. Zeke had acted with the same hotheaded zeal as the South Carolinians whom Clay and other border-state Union men condemned. He had failed to show a moderation in politics that Clay expected of all his sons and, more personally, he had reneged on his promise to remain at home during the war. Zeke evidently preferred to follow the lead of “every scamp in the country” rather than his own father’s, Brutus thundered to his wife. Ann agreed with his assessment, having already vowed to find out what it was that had “induced a boy to take sides against a father.” To the Clays, this was no ordinary disagreement of two individuals over sectional politics; rather, it was a very personal case of filial defiance.14

Other Union fathers had the same angry reaction to the secretive departures of their rebel sons. Although they had given their sons latitude to develop independent political views, few had known how seriously to take their sons’ expressions of Southern loyalty; fewer yet expected that their worst fear — Confederate service — would be realized. Union fathers therefore had difficulty knowing how to respond. If they accepted their sons’ defection as an independent act of political conscience, then they would be acknowledging the outright rejection of their own political views. But if they attributed it to reckless and defiant behavior, as Brutus Clay seemed to do, it would be much easier to remain secure in their position as fathers. The sons’ action would still represent a serious betrayal, but a more familiar and manageable one: it was just another coming-of-age struggle set against the dramatic backdrop of war.15

Fathers of the Civil War generation were well acquainted with this kind of conflict. Little consensus existed in midcentury prescriptive literature about the ideal relationship between fathers and sons. The historic tradition of paternal authority was being eroded gradually by an antebellum trend toward a less authoritarian and more affectionate model of child rearing. This left fathers and sons caught between expectations of paternal dominance and the impulse toward companionship. Where a father’s authority and a son’s deference met was rarely clear, and this created what historian Bertram Wyatt-Brown has called an “inherent ambivalence” between fathers and sons. Conflicts with fathers thus became a ritual of growing up for nineteenth-century sons, and this is what Civil War fathers often saw in their sons’ defection to the Confederacy: a very familiar and personal challenge to their paternal authority.16

Newspaper observers encouraged Union fathers to view their sons’ Confederate service as a deliberate act of filial defiance. In one of the first analyses of divided fathers and sons in 1861, the Louisville Daily Journal published a series of articles, entitled “Letters of a Father,” elaborating on why the present rebellion of sons was a normal stage in life. The American “political and social system” contained an inherent contradiction, the series argued, one in which sons were required to defer to their fathers while at the same time were instilled with republican values of liberty. The most readily available expression of that liberty was the rejection of “filial piety” in the home, and for that reason father-and-son conflicts were a natural creation of the republican system. The rebellion of sons in wartime was merely a reflection of this greater flaw in the American “national character”; worse, however, was the Confederacy’s exploitation of this phenomenon with “specious appeals to the natural love of liberty.”17

Indeed, the Confederacy’s call for independence meshed well with this younger generation’s desire for autonomy. At least one study of secession has found that young men felt a natural affinity for the Southern cause precisely because of the desire for liberty nurtured in their own homes. Fathers, the guardians of their inheritance and future livelihood as the owners of land, slaves, and family businesses, at times posed a substantial obstacle to their sons’ transition to adulthood. A father who was unwilling to give up land or otherwise assist his son in building an independent life f...