eBook - ePub

The Civil War in the West

Victory and Defeat from the Appalachians to the Mississippi

- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

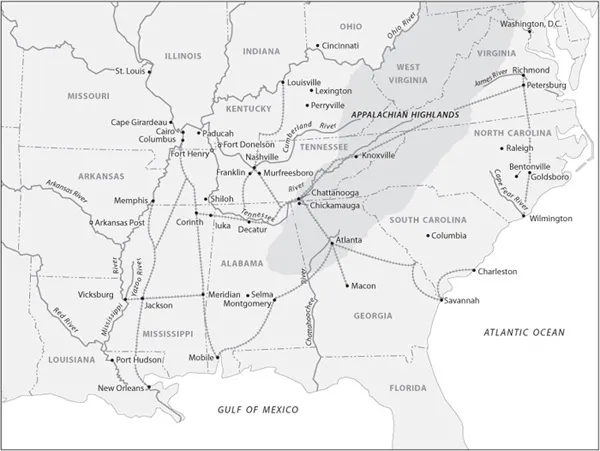

The Western theater of the Civil War, rich in agricultural resources and manpower and home to a large number of slaves, stretched 600 miles north to south and 450 miles east to west from the Appalachians to the Mississippi. If the South lost the West, there would be little hope of preserving the Confederacy. Earl J. Hess’s comprehensive study of how Federal forces conquered and held the West examines the geographical difficulties of conducting campaigns in a vast land, as well as the toll irregular warfare took on soldiers and civilians alike. Hess balances a thorough knowledge of the battle lines with a deep understanding of what was happening within the occupied territories.

In addition to a mastery of logistics, Union victory hinged on making use of black manpower and developing policies for controlling constant unrest while winning campaigns. Effective use of technology, superior resource management, and an aggressive confidence went hand in hand with Federal success on the battlefield. In the end, Confederates did not have the manpower, supplies, transportation potential, or leadership to counter Union initiatives in this critical arena.

In addition to a mastery of logistics, Union victory hinged on making use of black manpower and developing policies for controlling constant unrest while winning campaigns. Effective use of technology, superior resource management, and an aggressive confidence went hand in hand with Federal success on the battlefield. In the end, Confederates did not have the manpower, supplies, transportation potential, or leadership to counter Union initiatives in this critical arena.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Civil War in the West by Earl J. Hess in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Spring and Summer 1861

The secession crisis inspired confused reactions among people across the Northern states that lay west of the Appalachian Highlands. Promises of a peaceful separation of the seven Deep South states had lulled many Northerners into the idea that breaking up the country might be inevitable, or even helpful in settling controversies concerning the spread of slavery in the Western territories. Others were more reluctant to countenance the destruction of the political unity that had been maintained through a system of compromise on that issue for eighty-five years. Most Northerners, however, simply did not know what to make of the newly created Southern government in Montgomery, Alabama, its pretensions to independence, or its future. Secession created a malaise among many in the free states, unresolved by the tempering stance of the outgoing James Buchanan administration and the incoming Abraham Lincoln regime.1

But the Confederate bombardment of Fort Sumter on April 12–14, 1861, altered everything. As John Sherman of Ohio put it, Sumter touched “an electric chord in every family in the northern states” and changed “the whole current of feeling.” Sherman admitted that he was shocked by feelings of “surprise, awe and grief” by the act of violence, but later thought: “It brings a feeling of relief; the suspense is over.” Benjamin Scribner of Indiana felt “animated with patriotism, for “the flag of the Union was to me a sacred object.” For many across the North, the key issue lay in a respect for law and order, which the new Confederate government had demonstrated it did not possess. Federal authorities could not afford to look the other way at this forcible seizure of a U.S. government installation. “There would be no end to it,” thought Walter Q. Gresham of Indiana, “and in a short time we would be without any law or order. We must now teach the Secessionists a lesson.” For Gresham, it was “all bosh and nonsense to talk about the North making war on the South. The South rebelled against the laws and makes war on the government.”2

Newspaper editors of all political leanings beat the tocsin of war by interpreting the firing on Sumter as an unpardonable act of violence to settle an issue that should have been handled through negotiation. It was both a threat and an insult to the government. “On one side stands rebellion, treason, anarchy,” declared the Chatfield (Minn.) Republican, while “on the other the government, patriotism, law and order.” Everything undemocratic was vested in the seat of government at Montgomery, while the principles of the founding fathers of the nation were vested in the hands of Lincoln’s new administration in Washington. The Indianapolis Daily Journal believed that “We are fighting for the existence of our own Government,” more than for “the destruction of that at Montgomery.”3

For some of the more progressive-minded citizens in the North, there was gratitude for what happened at Sumter. The overt act of violence and lawlessness taught Northerners what they could expect from a slave Confederacy on their border. College professor and Republican state senator James Garfield of Ohio hoped the war would not end until the Confederacy was blotted out of existence, along with the institution that underpinned its economy, society, and culture. Another member of the Ohio Senate, Jacob Cox, vividly recalled how news of Sumter was announced during a session of that august body, causing “a solemn and painful hush” until a well-known abolitionist in the gallery shouted “‘Glory to God!’” Cox, along with most of the other legislators, could not share such enthusiasm for the moral redemption of the nation, but he steeled himself for the war by thinking that the sacrifice could only be justified by preserving thereby “the right to enforce a fair interpretation of the constitution through the election of President and Congress.”4

Whether Northerners welcomed Sumter because they saw that it foretold the death knell of slavery, or simply viewed it as an alarm for the defense of fundamental values held dear by the country, the firing on the fort solidified a common cause among Northern residents. Support for making war on the Confederacy was nearly universal, grounded on the need to defend the flag and all that it symbolized. Only the bombing of Pearl Harbor eighty years later had a similar effect on the American people, dispelling lingering feelings of isolationism and forming a mighty consensus in favor of war to the end.

There was an issue that quickly emerged among Northerners as another motivation for fighting. In fact, for many in the upper Mississippi Valley, it was as important as the motive to preserve the Union. This issue involved possession of the Mississippi River, a vast artery of commerce and communications. It had been in full possession of the common government since 1803, at enormous expense to the nation to secure its citizens full control not only of the waterway but also of New Orleans, the major port whereby Western farmers offered their products for shipment outside the country. Many Northerners wondered what secession would do to their historic right to navigate and use the great river, for it seemed to portend a reversion to the old days when Spain and France alternately possessed New Orleans, as well as the vast, undeveloped Louisiana Territory that stretched west of the Mississippi.5

The Western Theater of Operations

Since 1803, technology had made the river far more important as a trading artery than it had ever been. The first regular steamboat travel on the Mississippi began in 1812, with increasing numbers of craft plying the turbid waters every decade. The steamboat era reached its peak in the 1850s, the same decade that cotton production soared to its height in the Deep South. In 1859–60 more than 2 million tons of goods were shipped to New Orleans from the extensive watershed of the Mississippi, amounting to nearly $300 million worth of property. From Cincinnati, 206 steamboats put into New Orleans that year; 172 arrived from Louisville, 110 from Memphis, and 526 from Pittsburgh. From St. Louis, the second most important trade city in the Mississippi Valley, 472 boats traveled to the Crescent City laden with goods from the upper valley.6

The Mississippi drained about 40 percent of the territory encompassed by the nation’s forty-eight states, a region as large as nine European countries combined. The Northern half of the river, with its high bluffs, needed relatively little improvement to support navigation. The Southern half, on the other hand, was broader, deeper, and had long stretches of nearly imperceptible banks. The most troublesome stretch of the river, from a navigational viewpoint, lay between Cape Girardeau, Missouri, and the Gulf of Mexico. While these two points lay only 600 miles apart on a straight line, the river meandered so much that a boat needed to travel more than 1,100 miles to get from one point to the other. Moreover, this region’s deltalike mix of land and water led to expansive overflows on a yearly basis that affected landscapes many miles to either side of the channel. The first levee along the Mississippi River was built with the first settlement of New Orleans; it was completed in 1727 to protect that low-lying city on the east bank, situated one hundred miles north of the river’s mouth. More levees were built northward along whichever bank seemed to need it during the following years. By the time of the Civil War, a fairly good system of embankments lined long stretches of the river, although with significant gaps. The majority of the levees, mostly constructed in the 1850s, were relatively low—only three or four feet tall.7

Steamboat commerce could be dangerous. The boats had a tendency to explode, hit snags, or burn because owners were free to build them to any standards they wished. It has been estimated that by 1860, 299 riverboats on the Western waters were damaged and another 120 totally destroyed. De Bow’s Review calculated that more than 1,800 people had been killed in steamboat accidents, and another thousand injured, up to 1848.8

Ironically, the decade of steamboat ascendancy also witnessed the fast rate of growth for a major competitor of the boats. Developed in the 1820s and 1830s, railroad technology took off in the 1850s with thousands of miles of track laid, mostly across the Northern states. Major trunk lines began to link the Northwest with the Northeast, beginning to divert commerce to a West-East orientation rather than West-South. Canals had also begun to do this as early as the 1830s, but the railroad was a far more potent competitor of the steamboat. While 58 percent of Western produce was shipped through New Orleans in 1820, that figure dropped to 41 percent by 1850 and decreased even more by the time of the Civil War. Though many Northerners were not aware of it, the importance of the Mississippi River as the linchpin of Western commerce had declined. It retained its regional and local significance, but in a larger sense could lay claim to sharing the national flow of goods between the Northwest, the South, and the Northeast. Even so, it had proportionately come to serve Southern interests as much as Northwestern by the 1860s, for many Deep South planters invested so heavily in large-scale cotton production that they did not grow enough food to feed their slaves. The Northwest readily satisfied this deficiency.9

Questions of future sovereignty over the Mississippi River surfaced long before the firing on Fort Sumter. As soon as South Carolina seceded in late December 1860, Northern editors asked if their readers could trust the Southern Confederacy’s promise to keep the river open to their navigation and trade. Even if they honored their pledge, Andrew Johnson of Tennessee pointed out, later generations of Southerners might not do so. William T. Sherman was certain that the temptation to tax Northern commerce on the river was so great as to be irresistible. “Collisions are sure to follow secession,” he wrote his wife, “and the states lying on the upper Rivers will never consent to the mouth being in possession of an hostile state.”10

Northern doubts about the Southern government’s policy exploded when Governor John Jones Pettus of Mississippi constructed a few gun emplacements at Vicksburg on January 12, 1861, only three days after the state seceded. Pettus acted on rumors that the North was sending a party of armed men down the river to reinforce Federal forts and arsenals in Louisiana. Pettus called out the militia, but the scare evaporated by January 15. This act inflamed opinion among many Northerners against secession, as threats of war emblazoned newspaper headlines across their section. “The Northwest will be a unit in maintaining its right to a free and unobstructed use of the Mississippi river,” proclaimed the Cincinnati Daily Gazette. Newspapers in Iowa, Illinois, and Minnesota claimed as much right to free navigation of the great river as Mississippi or Louisiana. “It is their right, and they will assert it to the extremity of blotting Louisiana out of the map,” threatened the Chicago Daily Tribune.11

Many editors in the Northeast recognized the vitality of Northwestern interest in free navigation of the Mississippi and predicted their sister section would go to war with the Deep South over that issue alone, even if the Federal government made no move in that direction. The Buffalo Morning Express had predicted, even before Pettus’s action, that “a tornado of indignation” would result from any Southern effort to “cut off from the commerce of the world” the farmers and tradesmen of the Northwest. Even Massachusetts newspaper editors suggested that the coming contest between North and South would be decided in the valley of the Mississippi, and the PittsburghEvening Chronicle warned the South that no one “who is acquainted with the robust character and resolute daring of the Western people can doubt the result of such a struggle.”12

Southerners could read Northern newspapers too, and they made strenuous efforts to assure Northwesterners of their good intentions. The Louisiana secession convention passed an ordinance of secession and a resolution guaranteeing free navigation of the Mississippi on the same day, January 26, 1861. The newly formed Confederate government in Montgomery moved forward along the same line, passing a bill to establish free trade that President Jefferson Davis signed on February 25. A trade bill, passed on February 18, and a tariff bill, passed on May 21, established a Confederate policy of prohibiting taxes on imports of agricultural products. Even so, Southerners expressed fear that the thorny issue might derail secession altogether by creating an implacable animus against dividing the length of the Mississippi between two sovereign states.13

A few dissenting voices in the North pointed out that the river no longer held the preeminent place in national commerce it once possessed. The Cincinnati Daily Commercial noted that four major railroad lines and the Erie Canal linked the Northwest with the Northeast and could completely supplant the Mississippi while forging an even tighter unity between two sections that shared much more in common than either shared with the South. The Confederacy could only hurt itself, the editor believed, if it blocked navigation on the Mississippi. He noted that, apart from purely economic considerations, there was a mystic character about the Mississippi and its commercial significance that had not faded, despite the new economic realities. Many people still believed it was important, because it was a view handed down to them by previous generations. But Abraham Lincoln, speaking for those who understood the new economic realities, still thought saving the Mississippi River was important enough to go to war for. A product of the Western frontier who had taken boatloads of agricultural produce down the river to New Orleans in 1828 and 1831, Lincoln pointed out that North-westerners could not accept any limit to their commercial opportunities and would not be content to rely solely on the railroads and canals. They wanted “access to this Egypt of the West, without paying toll at the crossing of any national boundary.”14

Some Northerners interpreted the river navigation issue as far more significant than mere commerce. They took a geopolitical view of the controversy, noting that the Mississippi stretched “its branches into the heart of the continent,” carrying the melted snow of the Rockies to the Gulf of Mexico. The river created a “physical unit” that was destined to be controlled by one government. Sherman fully agreed with this point, noting that the river and its branches made separation of North and South impossible. The Mississippi River was a symbol as well as an avenue of trade—a symbol of progress, regional pride, and national sovereignty that physically tied the North and the South. While it was an intensely Northwestern issue, the feeling was understood and supported by the Northeast and taken seriously by the South. The Northwesterners shared their sectional neighbors’ reaction to the firing on Fort Sumter, but they had a special reason, in some ways more important than Sumter, for making war on the Confederacy.15

Kentucky Neutrality

Lincoln’s call for troops on April 15, 1861, was rejected by many in the Upper South slave states. Supportive of the right to secede, but having decided that the election of a Republican president had not been a justified cause of it, those residents now refused to support Lincoln’s efforts to use military force to restore the Union. Four more states seceded (Virginia, North Carolina, Arkansas, and Tennessee), constituting a formidable bulwark against Federal invasion of the Deep South. The northern border of the growing Confederacy now rested against an additional tier of slave states for most of its length. These border states (Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri) remained in the Union because public opinion was so deeply divided on the national crisis that a legitimate secession movement proved impossible.16

The border states represented the threshold between contending sections, with important ties to both of them. While the Federal government took halting but effective steps to secure them in 1861, Kentucky adopted a unique approach to the sectional crisis that inhibited both belligerents from setting foot on its soil for several months. Governor Beriah Magoffin defended slavery as well as the right of secession, and he rejected Lincoln’s call for troops. Though many Kentuckians agreed with his stand, they argued that the state ought to reject Confederate attempts to woo Kentucky into the Southern camp as well. A group of Kentucky politicians, comprising the State Rights Party, advocated secession, but they were not strong enough to sway the state in that direction. Although he cooperated with key secessionists to form Kentu...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- The Civil War in the West

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Map and Illustrations

- Preface

- 1 Spring and Summer 1861

- 2 Fall 1861

- 3 Fort Henry to Corinth

- 4 Occupation

- 5 The Gulf

- 6 Kentucky and Corinth

- 7 Winter Campaigns

- 8 The Vicksburg Campaign and Siege

- 9 Occupation and Port Hudson

- 10 From Tullahoma to Knoxville

- 11 Administering the Western Conquests

- 12 Atlanta

- 13 Behind the Lines

- 14 Fall Turning Point

- 15 The Last Campaigns

- 16 End Game

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index