eBook - ePub

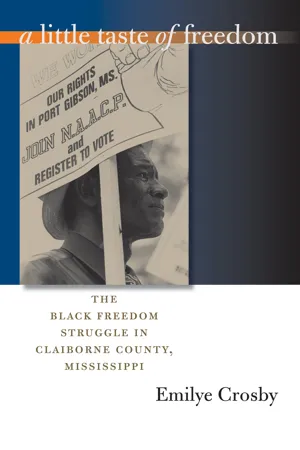

A Little Taste of Freedom

The Black Freedom Struggle in Claiborne County, Mississippi

- 376 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In this long-term community study of the freedom movement in rural, majority-black Claiborne County, Mississippi, Emilye Crosby explores the impact of the African American freedom struggle on small communities in general and questions common assumptions that are based on the national movement. The legal successes at the national level in the mid 1960s did not end the movement, Crosby contends, but rather emboldened people across the South to initiate waves of new actions around local issues.

Escalating assertiveness and demands of African Americans — including the reality of armed self-defense — were critical to ensuring meaningful local change to a remarkably resilient system of white supremacy. In Claiborne County, a highly effective boycott eventually led the Supreme Court to affirm the legality of economic boycotts for political protest. NAACP leader Charles Evers (brother of Medgar) managed to earn seemingly contradictory support from the national NAACP, the segregationist Sovereignty Commission, and white liberals. Studying both black activists and the white opposition, Crosby employs traditional sources and more than 100 oral histories to analyze the political and economic issues in the postmovement period, the impact of the movement and the resilience of white supremacy, and the ways these issues are closely connected to competing histories of the community.

Escalating assertiveness and demands of African Americans — including the reality of armed self-defense — were critical to ensuring meaningful local change to a remarkably resilient system of white supremacy. In Claiborne County, a highly effective boycott eventually led the Supreme Court to affirm the legality of economic boycotts for political protest. NAACP leader Charles Evers (brother of Medgar) managed to earn seemingly contradictory support from the national NAACP, the segregationist Sovereignty Commission, and white liberals. Studying both black activists and the white opposition, Crosby employs traditional sources and more than 100 oral histories to analyze the political and economic issues in the postmovement period, the impact of the movement and the resilience of white supremacy, and the ways these issues are closely connected to competing histories of the community.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Little Taste of Freedom by Emilye Crosby in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER One Jim Crow Rules

Claiborne County, and its county seat of Port Gibson, located near the Mississippi River just south of the Delta, was one of Mississippi's first white settlements. On the eve of the Civil War, the community was dominated by cotton planters and mercantile traders, with Negro slaves outnumbering whites almost five to one. The Civil War and Confederate defeat brought a dramatic short-term reversal of fortune to both planters and slaves. In 1860, there were 3,339 whites, 12,296 enslaved African Americans, and 44 free blacks in the county. Seven years later, blacks had helped the Union army win significant battles, the Thirteenth Amendment had banned slavery, and black voters outnumbered white 1,015 to 9.1

In addition to being disfranchised by Reconstruction policies, planters faced huge debts and an uncertain labor force as they attempted to rebuild their plantations and economy. Adjusting to military defeat, they also had to confront a world in which blacks, whom they perceived as childlike, inferior, and dependent, embraced freedom, citizenship, and political participation. Dismayed when enslaved people left plantations to join Union troops, planters were further troubled by the post–Civil War political alliance of freedmen and white Republicans. During Reconstruction, black Claiborne Countians served in a number of important appointive and elective political positions, including mayor, sheriff, president of the county governing board, postmaster, and even U.S. senator, when Hiram Revels held that position in 1870. In 1871, the Reconstruction government of Mississippi purchased the campus of Oakland

State of Mississippi and Claiborne County and Vicinity

College, a forty-year-old Claiborne County school for the sons of planter elite, which had closed during the Civil War. Built by slave labor, Oakland was renamed Alcorn (for the state's Republican governor) and became the first state-supported black college in Mississippi. Though Alcorn remained physically isolated and severely underfunded, it became an important source of opportunity for African Americans, especially those in the immediate area.2

Most black gains during Reconstruction were short-lived. White Mississippians used fraud, intimidation, and violence in the 1874 and 1875 elections to restore white supremacy and bring to power what became an all-white Democratic Party. Though blacks and their Republican allies struggled to protect their political rights, they were overwhelmed by extensive violence and lawlessness. For example, in Vicksburg, about twenty miles north of Port Gibson, whites forced the black sheriff out of town and overpowered those who gathered to support him, killing as many as 300 African Americans. President Ulysses S. Grant declined to send in federal troops, and Adelbert Ames, Mississippi's Republican governor, was himself forced to leave the state. By 1877, Reconstruction and the promise of racial equality had been destroyed nationwide.3

Well into the twentieth century in Claiborne County, black/white interactions were shaped by the legacy of slavery and the system of sharecropping that replaced it. Initially employed in Claiborne County in 1869, sharecropping was firmly established by the 1880s and varied little until the early 1930s. Sharecroppers contracted with planters to work a plot of land in exchange for a portion of the cotton and corn crops, usually one-half or one-third, depending on whether the landowner or tenant provided livestock, equipment, seed, and living expenses. Even when farmers around the country began using tractors and other forms of mechanization, cotton farmers relied primarily on their own labor, plowing, planting, chopping (weeding), and harvesting with only the most rudimentary of tools—plows, hoes, and mules. As late as 1930, 81 percent of African American workers in Claiborne County were involved in agriculture, and the demands of the cotton season shaped every aspect of black life—work, school, housing, food, religion, and recreation.4 Sharecropping was ostensibly an economic contract and started out as a compromise between plantation owners who had little money for wages and former slaves who wanted land of their own to work in family units. A white planter reflected in the 1990s that he and other whites thought tenant farming was “a good system” that was “fair to everybody.” However, planters had vast power and could intrude at will into the lives of their tenants.5

Claiborne County sharecropper Annie Holloway's interactions with white planter Leigh Briscoe Allen provide a good illustration. Before agreeing to move onto Allen's plantation, Holloway tried to ensure that she and her husband have a measure of autonomy. Since she intended to do most of the field work while her husband farmed around his day job at the Port Gibson Cottonseed Oil Mill, she asked Allen if he had to “see my husband in the field everyday.” Her question reflects the common understanding that whites expected both a share of the harvest and to control their tenants’ time. Allen agreed to Holloway's proposal, but, as she had expected, he still kept close watch over them and their crops. Holloway recalled that her husband “was working like I don't know what. He wouldn't let a vine get up on top of that cotton, ‘cause Mr. Allen might ride down the road and see it.” Once when Allen found the Holloways at home celebrating their first bale of cotton, he made it clear that only extreme illness could justify their midday absence from the cotton fields.6

Annie Holloway Johnson, landowner and voting rights activist, holding pictures of her second husband, Arthur Johnson, and an unidentified person. Photograph by Roland L. Freeman, courtesy Roland L. Freeman.

Planters governed choices about crops, growing practices, and land use, such as whether tenants could plant a garden. Tenants generally subsisted on field peas, sweet potatoes, and corn. When they could, they planted a garden to supplement those staples with fresh vegetables in the summer and canned produce in the winter, providing a more varied diet and less need to purchase food on credit. However, planters often insisted that tenants plant only cash crops.

Children on the porch of typical sharecropper house in Rodney, Mississippi, just south of Claiborne County, 1940. Photograph by Marion Post Wolcott, courtesy Library of Congress, LC-USF 34 54956-E.

Until a New Deal government official promoting diversified agriculture intervened, Allen made Holloway plant cotton right up to the house. Another tenant asserted that her landowner was a good man to work for in part because he “didn't keep us from raising a garden.”7 Tenant housing was linked to the sharecropping arrangement and usually consisted of small, poorly constructed shacks full of holes and cracks. Almost all lacked plumbing and were difficult to keep warm in the winter. One sharecropper recalled that his family's calf once walked right through a hole in the wall. Katie Ellis described tenant houses as “barn houses” and said she was “dying for to have a place of my own.” One black man became determined to “get my mama a little old place to build her house” when a white planter refused to let him cross a field to visit his mother. Blacks who were unable to buy their own homes often did what they could to improve the tenant houses. Annie Holloway, for example, covered the interior of Allen's tenant house with cardboard to try to seal it and then covered the cardboard with paper for decoration. She also purchased and installed glass windows after explicitly getting Allen's permission to take them with her if she moved.8

The white dominance that accompanied sharecropping helped planters tie tenants to their land and ensured a steady labor force. A former planter said that he preferred sharecropping to a simple renter's agreement for cash because “you had quite a bit more difficulty with that man that's paying cash,” but “these fourth and half guys, they couldn't sell that stuff without you and him agreeing on it. That was a big difference, don't you see.” He observed that cash renters were free to move if they wanted and concluded, “[If] he tells you goodbye, you see where you are, don't you see.” However, whites’ desire for control went beyond this profit motive. According to Jesse Johnson, the white man he rented land from resented Johnson's insistence on a business relationship as equals, including Johnson's determination to get receipts for the purchases he made on credit. “See, he just wanted you come there and get whatever you want, but don't get no receipt or nothing. And we didn't do it. And that's why he didn't like us.” In fact, Johnson asserted that his independence and success bothered his landlord more than the poor crops of other renters. He explained, “Them other fellows, he told them how to farm, and grass overtook their crops,” but “we told him we was renting this land, and all he was looking for was his rent. And we were going to work it like we wanted.”9

Although plantations had much in common, tenants made distinctions based on things like a planter's willingness to permit their children to attend school, provide medical care, or allow autonomy. Katie Ellis, for example, contrasted her landlord, who “just rent the land to us and that was all,” with those who “tried to keep you under their thumb.” William Walker grew up in a sharecropping family and spent his adult life as a sharecropper on the Person plantation. He spoke positively of the whites his family associated with, including the family that “mostly raised” his father and “taught him how to read and how to tend to business.” As for his own experience, he said, “[I] never have farmed with but one man and that was Mr. Person. And it was just like a home. We didn't own it, but we was at home.” Despite concurrent memories of hard times and mounting debt, he described Person as a benevolent father figure: “Mr. Jimmy, he would always take care of us. And he'd send you to the doctor. You never had to worry about no doctor, and if you had to go to the hospital, he send you to the hospital. And he would foot the bill ’til we get up able to do so.” Even though tenants had to repay the bills with interest, access to medical care was no small thing. When Minnie Lou Buck's two-year-old daughter broke her arm, all Buck could do was wrap the arm in clay and vinegar and a homemade splint. She recalled, “That child suffered. And that arm just swole up.”10

The yearly account of charges made against the cotton crop (which included everything from groceries and doctor's bills to farm equipment and fertilizer) was a constant source of conflict. By harvest time, sharecroppers owed planters their share of the crops and payment for any advances of money and supplies, including interest that ranged from 15 to 25 percent. Whites generally kept the only records and resisted, sometimes violently, black efforts to keep their own accounting. In the best of circumstances, the debt and interest made it difficult for sharecroppers to make money, and few worked in an ideal situation. Planters could decide when and to whom tenants sold cotton, or they could buy it and store it for later resale, keeping any additional profit. Most important, however, planters decided how much tenants owed and what compensation they would receive for their year's work. Annie Holloway asserted, “You ain't gon’ figure yourself, and they not gon’ figure it for you. They gon’ just give you something when it's all over with.” She described a conversation that took place when she asked for an explanation of the yearly cotton settlement: “The one I was talking to that really fixed the paper and gave it to my husband, he couldn't say nothing. The other one said, ‘That's what I say about you niggers: you doing better than you ever did in your life and you still ain't satisfied.’” Holloway concluded, “If you say anything to them about it, they go to cussing. He'd take the whole crop and give you something. Didn't settle up with you.” Such white control could have dire consequences. In 1925, for example, after Frances Pearl Lucas's father was killed, she remembered, “The man would take all the crop from us, and Mama had six children . . . to feed and take care of. Didn't have nothing, didn't have no hogs or nothing to kill. And they'd take all we'd make. . . . My mother gave us away to anybody. She couldn't take care of us.”11

There were rare exceptions when landowners based their settlements on written receipts and were perceived as relatively fair. G. L. Disharoon and his relatives had a reputation for being good to work for. Reverend Eugene Spencer, who became an important leader in the black community, described Disharoon as “the aristocratic type, a gentleman, so to speak, as he dealt with people.” When Spencer was a young man, Disharoon told Spencer's uncle, “If you want Eugene to keep books for the records, it's all right with me.” Spencer concluded, “He didn't want anything but his—and I did keep the records.” Yet even Disharoon rarely came up with the same numbers as his tenants. Another one of his former sharecroppers recalled, “[He] kept an account of all that I got from him. I kept an account of what I got, [too]. Sometimes I go, I needed some things. . . . I had to wait on the charge. And he say, ‘I ain't gonna charge you much.’ See, when I get ready to pay him, it was more than I expect.” A longtime tenant summed up sharecropping: “You do all the work, and then the man, at the end of the year, the man get the money. You wouldn't get nothing out of it. I didn't understand it. I never liked working on the half.”12

Tenants had little choice but to accept the settlement given by planters. Most share agreements were verbal, though it hardly mattered. The inequities were protected by white supremacy and the closed nature of rural Mississippi. Historian Neil McMillen argues that, even after Emancipation, planters still “thought of the people who worked their fields as ‘their niggers,’ subject to their authority.” When Reconstruction ended and the federal government adopted a hands-off policy in terms of southern racial issues, blacks had nowhere to appeal. The law was allied with the interests of planters and provided no relief. According to historian Nan Woodruff, “Wherever African Americans turned, they encountered a world circumscribed by constables and justices of the peace who constantly harassed them . . . [and] by plantation managers who also served as deputies, by planters who had the power to protect their workers from arrests or to send them to the state penitentiary, and by enough lynchings to remind them of the costs involved in defying the brutal instruments of domination.”13

Unquestioned authority over the yearly crop settlements and final say over things like credit, medical care, and housing were part of the everyday, even mundane, manifestations of white supremacy. Violence produced the menacing backdrop that gave it potency. Blacks who wanted to protest their settlement or any affront at the hands of whites had to carefully calculate the possible costs. Between 1889 and 1945, there were six recorded lynchings of blacks in Claiborne County and adjacent Jefferson County. Moreover, white violence against blacks was sanctioned by the legal system and the larger white community. One black man recalled that when he was growing up, white children would “meddle with you.” If whites “hit you . . . look like nothing you could say. They kill you back there in those days.” In the 1940s, a white man killed a black soldier over $1.30 in a gambling game and teenaged white brothers killed a black youth in a dispute about a bicycle.14

In 1906, John Roan, a white man, killed Min Newsome, a prosperous black farmer and his former childhood playmate. According to his son, Newsome, who was successful enough to have a team of mules, a mare, a wagon, and a surrey, was working day and night to clear the 160 acres of swamp land he was purchasing. In a vaguely worded report, the local newspaper attributed the killing to self-defense after an argument, but Newsome's family maintains that Roan killed Newsome because he was jealous and believed the land Newsome was buying was “too good for a black man to have.” The courts never indicted Roan, and despite the partial payment made by Newsome before his death, all the land ended up back in the hands of its original white owner.15

Similarly, in 1939, Farrell Humphrey killed a black farmer named Denver Gray. According to family stories, even as a young man Gray “didn't take no stuff off white folk.” When he was sixteen, his family sent him to St. Louis because he had fired a shotgun at a white man who was “winking and beckoning” at one of his female cousins. When Gray returned to Mississippi, he still “didn't cow to white folks, and people thought he was crazy because if he saw a white man bothering anybody colored, he stop him. They didn't like that.” According to Gray's daughter Hystercine Rankin, Humphrey shot her father in broad daylight on a county road, then went and told Gray's wife where his body was. Later, he bragged about killing an “uppity nigger.” Evidently Gray's offense was talking back and buying his wife a new coat and stove, rather than purchasing secondhand ones from Humphrey.16

Humphrey was never punished, and in telling the story of her father's murder, Rankin began by explaining that white men had raped her grandmother and great-grandmother and both had conceived children as a result. She continued, “White folks could do anything they wanted to in those days, and if one of our men said something, they'd just kill him.” She describ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- A Little Taste of Freedom

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Preface

- CHAPTER One Jim Crow Rules

- CHAPTER Two A Taste of Freedom

- CHAPTER Three Adapting and Preserving White Supremacy

- CHAPTER Four Working for a Better Day

- CHAPTER Five Reacting to the Brown Decision

- CHAPTER Six Winning the Right to Organize

- CHAPTER Seven A New Day Begun

- CHAPTER Eight Moving for Freedom

- CHAPTER Nine It Really Started Out at Alcorn

- CHAPTER Ten Everybody Stood for the Boycott

- CHAPTER Eleven Clinging to Power and the Past

- CHAPTER Twelve Seeing that Justice Is Done

- CHAPTER Thirteen Our Leader Charles Evers

- CHAPTER Fourteen Charles Evers's Own Little Empire

- CHAPTER Fifteen A Legacy of Polarization

- CHAPTER Sixteen Not Nearly What It Ought to Be

- CONCLUSION What It Is This Freedom?

- EPILOGUE Looking the Devil in the Eye Who Gets to Tell the Story?

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgments

- Index