eBook - ePub

Imprisoned in a Luminous Glare

Photography and the African American Freedom Struggle

- 312 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In Imprisoned in a Luminous Glare, Leigh Raiford argues that over the past one hundred years, activists in the black freedom struggle have used photographic imagery both to gain political recognition and to develop a different visual vocabulary about black lives. Offering readings of the use of photography in the anti-lynching movement, the civil rights movement, and the black power movement, Imprisoned in a Luminous Glare focuses on key transformations in technology, society, and politics to understand the evolution of photography’s deployment in capturing white oppression, black resistance, and African American life.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Imprisoned in a Luminous Glare by Leigh Raiford in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Photography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 No Relation to the Facts about Lynching

On Thursday, November 30, 1922, James Weldon Johnson, executive secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), sat in his by-then familiar place in the gallery of the United States Senate. Johnson watched wearily as the fruit of the labor of thousands of women and men worldwide slowly rotted below him. After more than two years of tireless lobbying, editorializing, propagandizing, fund-raising, and protesting, the fight for the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill was coming to an end. The Dyer bill, the first legislation of its kind sponsored by the NAACP, sought “to assure persons within the jurisdiction of every state the equal protection of the laws, and to punish the crime of lynching.” It proposed to do so by holding state government officials culpable for failing to curtail lynchings or to bring lynchers to justice, threatening fines or imprisonment for such failure, and securing monetary restitution for the families of lynching victims. In conjunction with the NAACP, Representative Leonidas Dyer (R-Missouri) first devised the bill in late 1919 as a response to the racial massacres earlier that year. Dubbed “Red Summer” by W. E. B. Du Bois, from July well into October scores of African Americans, including many World War I veterans, were lynched, burned, and driven from their homes by irate white mobs in cities throughout the United States. Dyer introduced the bill into Congress in April 1921 and, finally after a very bitter struggle—delays bringing the bill to the floor, fierce opposition from southern Democrats, and extensive organizing on the part of the NAACP— the House passed the bill on January 25, 1922, by a vote of 230 to 119. From there the bill headed to the Senate, where the Democrats, led by a strong cadre of southern senators, mobilized opposition against federal intervention into southern affairs, specifically the handling of local “Negro problems.” The Democrats threatened a filibuster, going so far as to lay down the ultimatum that they “would not allow any government business whatsoever to be transacted until the Anti-Lynching Bill was withdrawn . . . for the entire remaining term of the 67th Congress.” Though the bill could be reintroduced into the next congressional term, beginning March 4, 1923, it would be dead if the Republican senators did not counter the filibuster. “The outlook is rather dark,” Johnson telegrammed his assistant Walter White that day. “But the fight is by no means yet lost. If we can only prevent the Republicans abandoning the bill on the terms laid down by the Rebels, we still have a chance.”1

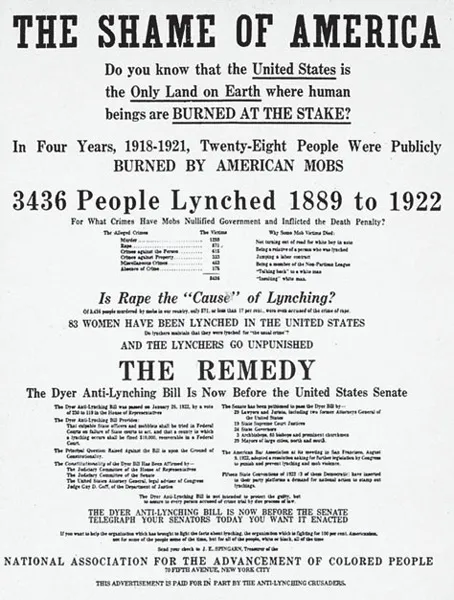

Figure 1.1. NAACP ad, “The Shame of America,” New York Times, November 22, 1922.

Just eight days earlier, the NAACP struck their boldest public move in the Dyer effort. On November 22, 1922, “The Shame of America” advertisement appeared in ten major white-owned newspapers throughout the United States, including the New York Times, the Atlanta Constitution, the Chicago Daily News, and the Nation magazine (figure 1.1). Full-page advance copies were sent to each member of the Senate on November 20. The ad posed the question to a national, largely white, mass readership, “Do you know that the United States is the Only Land on Earth where human beings are BURNED AT THE STAKE?” Assistant secretary Walter White and publicity director Herbert Seligmann designed the advertisement, which was paid for by the Anti-Lynching Crusaders, a short-lived umbrella organization of black women's groups nationwide dedicated to raising money and awareness for the NAACP'S antilynching campaign. Following the strategy pioneered by activist Ida B. Wells, the ad combined lynching statistics, a refutation of rape as the cause of lynching, and an outline of the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill itself, ultimately affirming the constitutionality of the bill, one of the alleged reasons for its being contested. The ad appeared in half-, full-, and two-page spreads. It was large and loud, meant to draw attention to and heap ignominy upon the country whose laws could not, and would not, protect twelve million of its citizens. It announced itself in a forum, the white print media, whose pages were filled primarily with reports of black crime, almost entirely ignoring black victimization and often black achievement.

James Weldon Johnson felt that the text of “The Shame of America” was deeply powerful yet firmly situated within democratic discourse. In large print that drew reader's eyes to “Rape”“BURNED,” “UNPUNISHED,” and “3436 People Lynched,” the ad proved striking enough to catch one's attention. But it was not so shocking that its message could be dismissed. It listed U.S. governmental apparatuses and individuals who had either affirmed the constitutionality of the bill (the judiciary committees of both the House and Senate, the U.S. attorney general) or lent their support to it (“19 State Supreme Court Justices, 24 State Governors, 39 Mayors of large cities, north and south”). With this notable register, the NAACP affirmed that the goal of the bill was to ensure equal access to due process, not to excuse crime, to guarantee order rather than promote lawlessness.

The “Shame of America” garnered an immediate and compelling response. The following day, November 23, 1922, White telegrammed Johnson that “The Times‘ad’ is certainly kicking up the biggest sensation in New York in many a day. . . . Every newspaper in New York City has had one or more representatives here [at the office] pleading to be allowed to repeat the advertisement in their papers.”2 In a 1924 pamphlet entitled “Lynching: America's National Disgrace,” Johnson expressed his own pleasure with the efficacy of the ad, stating that “it constituted the greatest single stroke of publicity propaganda ever made in behalf of justice of the American Negro.” And in his 1933 autobiography, Along This Way, Johnson asserted that this publicity “probably caused more intelligent people to think seriously on the shame of America than any other single effort ever made.” Like a camera's flash illuminating a scene too dark for the naked eye, the NAACP described itself as “the organization which has brought to light the facts about lynching.”3

So compelling was this ad that White and Seligmann drafted a second version that would incorporate photographs of lynchings. This version was to appear in the December 14, 1922, issue of the New York Times Mid-Week Pictorial. Begun in 1914 as a forum for the deluge of war photographs pouring in from Europe, by 1922 the Wednesday and Saturday “pictorial editions” were precursors to photo magazines to come, such as Life and Look. The newspaper featured photographs and photographic advertisements primarily in this twice-weekly format, which, according to White, had “a circulation of 62,500. . . . Eleven per cent of that circulation is local, 89% nation-wide.” The Times offered the NAACP a “good” price for the placement of the new version, $250, and White urged Johnson to approve the copy and give the go-ahead. “Yes, it is another page in The Times which will include photographs of lynchings and will answer the arguments that the Southerners are attempting to advance,” White telegrammed Johnson on November 29. White seemed to think this new ad was the most effective one the NAACP had produced to date. This new version would serve up a potent marriage of legal fact and visual document, a union that the assistant secretary believed could not be ignored. White closed his letter to Johnson with the rhetorical question: “Don't you think it is time for us to take off the bridle and use the sledge hammer? Personally, I do.”4

But as Johnson sat in the gallery the next day and watched the Democrats hijack the Senate floor and the Republicans sit by idly, he wondered if the sledge hammer, the photograph as blunt instrument, this late in the fight would prove the right weapon for the job. Johnson wired White on the morning of November 30 at his home and wired him again that afternoon at the Fifth Avenue offices of the NAACP, both times with the same message regarding the photographic version of “The Shame of America”: “I [will] wait for the copy of the ad, but I [doubt] that the proposed ad would have any effect on the present situation here. You see the crisis on the bill has no relation to the facts about lynching! Indeed, the facts about lynching have up to this time played an almost negligible part in the whole Senate fight.” The facts, Johnson seemed to think, no matter how volatile or visceral their presentation, fell short in the quest to gain black subjectivity within the law. A photograph could not prove the bill's constitutionality. A photograph could not change the centuries-long tradition of white violence in the South. Or could it?5

Johnson's reticence was certainly born of the “politricking” he witnessed during the course of the Dyer fight, the active marginalization of black citizenry, and the aggressive disregard for their concerns and complaints accomplished through the formal mechanisms of government. That Johnson expresses this dilemma over and about the form and force of “publicity propaganda” urges us to consider the possibilities and limitations engendered by the use of photography in the antilynching struggle. Since its inception in 1909, the NAACP regularly reproduced photographs of lynchings in their many antilynching pamphlets (about three per year between 1909 and 1922), in issues of Crisis, the organization's news organ edited by W. E. B. Du Bois, and even as printed postcards. Following the lead of journalist and activist Ida B. Wells, who first included lynching images in her 1893 essay “Lynch Law” and again in her 1895 investigative pamphlet A Red Record, the NAACP similarly chose to arm itself with photographs as weapons in its arsenal of evidence. Photographs, celebrated for their veridical capacity, as documents of “a truly existing thing,” could stand side by side with other forms of “proof”—statistics, dominant press accounts, investigative reports—utilized by these antilynching activists to offer testimony to lynching's antidemocratic barbarism. Wells and the NAACP augmented their literature primarily with professionally made photographs of lynchings. Widely circulated and relatively easy to obtain, these images were readily available for public consumption.

“Readily available,” however, does not mean easily digested, transparently comprehended, or resolutely acted upon. For White, photographic images stood as the most decisive fact among facts. His enthusiasm for the second layout of the “Shame of America” reveals a faith in the truth-telling and democracy-building work of photographs, that the good, white citizens comprising the Times readership need only see the horrible reality of lynching to be moved to end it. But in Johnson's grim diagnosis, facts could be, and often were, easily ignored or simply fit into a patently antiblack framework. The facts of lynching—evidence of the true violence that coerced compliance and defined the terrain of black life—meant little without a new lens through which to view and interpret them. Social change, we might infer from Johnson's frustration, cannot take root without the radical renovation of racial consciousness.

White's certainty and Johnson's lack of confidence in the power of photography to accurately and movingly represent the absurd brutality of lynching reveal inherent ambivalences about the employment of the photograph as part of social movement strategy. Their exchange speaks to a keen awareness on the part of these deeply committed and highly accomplished activists of photography's revelatory potential, and also to the nagging apprehension that the photograph may occlude more about black existence in the United States than it exposes. It testifies to black engagement with the discourses and techniques of American modernity (mechanical reproduction of the photographic image being a signal technological achievement), while also belying a fundamental critique of modernity and its cultural logics. It wrestles with the question of whether the photograph could successfully shoulder the evidentiary, sentimental, and political burdens placed upon it, or if it would flounder and collapse under the weight of these multiple demands. White and Johnson's telegrammed conversation illuminates the collision and collusion of political representation and cultural representation in the context of the long African American freedom struggle that lay at the heart of this study; photography as apposite to political struggle and yet also as aporia.

This chapter interrogates the battle waged by antilynching activists to reframe lynching discourse with and through photography, and the implications of such reframing for black viewers. First, through an examination of lynching and antilynching photography in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, I reveal these images to be a site of struggle over the possession of the black body between white and black Americans in this period, about the ability to make and unmake racial identity. In the hands of whites, photographs of lynchings, circulated as postcards in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, served to extend and redefine the boundaries of white community beyond the localities in which lynchings occurred to a larger “imagined community.” In the hands of blacks during the same time period, these photographs were recast as a call to arms against a seemingly never-ending tide of violent coercion and transformed into tools for the making of a new African American national identity. Similar, if not the same, images of tortured black bodies were used to articulate—to join up and express—specifically racialized identities in the Progressive Era, a period marked by the expansion of corporate capitalism, the rise of the middle classes, and the birth of consumer culture. It is necessary to ask: what is the process by which activists transformed lynching photographs, advertisements for and consolidators of white supremacy, into “antilynching photographs,” testaments to black endangerment? How exactly were photographs that celebrated the triumph of “civilization” made to herald civilization's demise?

By uncovering and pulling apart the threads of white supremacy and black resistance invested in these photographs, we can also begin to understand how lynching photography unmakes racial identity. Indeed, the very need to use photographs in campaigns for racial domination or racial justice points to cracks and fissures in these identities. Exposed are the social, sexual, political, and class anxieties that the framing of these images attempt to deny. In their various contexts and incarnations, we can discern how lynching photographs create and coerce, magnify and diminish, the appearance of unified racial identities. In the creative hands of antilynching activists especially, these photographs were employed to critique the racial logic from which they initially emerged. In doing so, Wells and the NAACP, the foci of this chapter, worked to recast the meaning of black identity and national belonging and illuminated the contradictions and ambivalences of racial ideology.

Antilynching activists’ employment of photography made available and discernible other ways of interpreting blackness in which the black body is read “against the grain,” in which alternative meanings of blackness are asserted. This effort to reinscribe the connotation of the lynched black body and its photographic representation is one born out of the “problems of identification” for black spectators.6 Indeed, if lynching photographs were meant for white consumption, to reaffirm the authority and certainty of whiteness through an identification with powerful and empowered whites who enframe the black body, what then did black looking affirm? What concept of the black self could emerge from an identification with the corpse in the picture? Can one refuse such identification, or is “the identification . . . irresistible”?7 Black identity of course is itself neither unified nor without its anxieties. The various contexts among African American audiences in which lynching photography, meant to do antilynching work, appeared, reveal a more variegated black spectatorship, highlight more clefts of class, gender, and geographic location than the image's singular focus on the hopeless figure at its center might initially suggest.

Johnson's lament, that the life-or-death fight for equal protection under the law has “no relation to the facts about lynching,” signals an antinomy embedded in the lynching archive, an antinomy produced through its repeated invocations and juxtapositions. Can photography serve to construct new racial epistemologies or does it always edify dominant paradigms? That is, can the black body (photographed) as abject and discredited sign be made to signify differently? Such conflicts alert us to the constraints faced by these early twentieth-century activists in deploying visual representation as a strategy for liberation, constrictions that later African American social movement activists would encounter, struggle with, and resist.

The Making and Unmaking of Blackness in the Progressive Era

The history of lynching in the United States is a long and brutal one. At its apex, between 1882 and 1930, this strain of America...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- IMPRISONED IN A LUMINOUS GLARE

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- CONTENTS

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- 1 No Relation to the Facts about Lynching

- 2 Come Let Us Build a New World Together

- 3 Attacked First by Sight

- CONCLUSION Or Was It the Pictures That Made Her Unrecognizable?

- NOTES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX