![]()

1

The Nature of Cycles

Nature animates itself in cycles. Some cycles, such as sleep and wakefulness or hunger and satiation, are of immediate concern. Others, such as the transition from day to night, or from spring to summer, to fall, and then to winter, are broader, encompassing other cycles. Because natural cycles occur at all scales of observation, from the motions of celestial objects to those of infinitesimal particles, they may seem too vast or too insignificant for us to comprehend, yet all these different natural rhythms combine harmoniously, like some vast musical score, to provide order, vitality, and charm to our world.

In the Southern Appalachians, the seasons constitute the most conspicuous and important natural cycle. The muted tones of winter swell into the melodious spring, settle into the deep harmonies of summer, and then, after the colorful fall cadenza, diminish into the pianissimo of winter. We eagerly anticipate the changes from winter snows to spring flowers, then to summer greenery and autumn leaves. Like us, Appalachian animals and plants also sense seasonal progression and prepare for the changes in form and tempo. Unlike most of us, however, they are fully engaged in each season’s performance, resonating with each note and responding as gently plucked strings.

Within that yearly cycle of the seasons, from spring to winter and back again, is an underlying daily rhythm, pulsing like a throbbing heart. The daily cycle, from dawn to dusk and then back to dawn again, is twenty-four hours long. After 365 daily beats, the yearly cycle has completed an entire revolution. Our bodies, as well as those of other living organisms, track and respond to these cycles. We have a biological clock as well as a biological calendar deep in our core.

Sleeping and waking, growing and shedding underfur or leaves, and migrating across continents are all cyclic patterns in nature. We know to expect an increase in bat and moth activity at night and to watch for waves of monarch butterflies in the first cool days of fall, just as the leaves of deciduous trees begin to change color, because the shift from day to night or summer to fall causes animals and plants to respond predictably. Long-term events, such as periods of mountain building or the advance and retreat of ice sheets, are also cyclic and encompass seasonal and daily rhythms. Such geological cycles have a profound influence on the composition of natural communities of living things. Daily, seasonal, and long-term cycles of change provide the organizational framework of this book, but the range of nested rhythms, like Emersonian circles, extends from the atomic to the astronomic and provides an assuring regularity to the music of the spheres.

Daily Cycles and Biological Clocks

Our moods, appetites, and energy levels change over the course of a day as our biological clock ticks. Most of us are asleep at 3 A.M. but awake at 9 A.M. We become hungry at about the same time each day. Our body temperature and blood pressure are lowest at night and highest during the day. These daily cycles (also called circadian rhythms) are generated by an innate biological clock. Even in the absence of environmental cues as when, for example, bean plants are kept in constant light or rats are kept in constant darkness, we still respond as if the sun is rising and setting. All organisms that have been studied, from bacteria to humans, have biological clocks that control recurring cycles of processes such as cell division, hunger, wakefulness, blood pressure, and body temperature. From the outset, we’ve all got rhythm!

Circadian rhythms, however, can be adjusted by cues from the environment. This flexibility allows environmental information, such as the shift in day length as winter becomes spring, to reset the clock. For example, a circadian rhythm is the cause of jet lag—when you suddenly arrive in a different time zone, your clock remains set to the old time and causes you to become sleepy at inappropriate times, but over the course of a few days, your biological clock is reset to the new time and you feel better, usually just in time for your return trip back to another time zone! In mammals such as ourselves, the clock is composed of a group of cells lodged in the hypothalamus of our brain. The hypothalamus, part of the forebrain, controls the secretion of many hormones that regulate behavior and biological processes.

The Daily Cycle of Sleep in Animals

The most obvious daily cycle in animals is the cycle of sleep and wakefulness. Diurnal animals are active during daytime and sleep during night, whereas nocturnal animals are active at night and sleep during daytime. But why do animals sleep? Wouldn’t it be advantageous to be awake all the time, constantly on watch for predators, food, or mates and able to respond immediately should one appear? Sleeping would seem to put an organism at a disadvantage, yet animals still sleep. There must be something to gain!

Perhaps the most general function of sleep is to conserve energy by reducing metabolism. In particular, small animals such as hummingbirds, shrews, and bats have very high metabolic rates that require huge amounts of food to sustain. While they are awake, they eat more or less constantly. Starvation is a very real threat to these small furnaces. Dead but uninjured shrews (see chapter 5) most likely died of starvation, especially in early spring, when nights are cold and food is scarce.

Hummingbirds (see chapter 2) feed during daylight only, when they can see the flowers and insects that provide them with high-energy food. And feed they must! The adult animal with the highest recorded metabolic rate (85 ml O2/g hr) is a hovering Allen’s hummingbird. Our Appalachian species, the ruby-throated hummingbird (Archilochus colubris), is no less impressive. When at rest, its heart beats 615 times and its lungs draw 250 breaths each minute. When flying, its wings beat seventy times each second and its heart rate doubles to around 1,200 beats per minute. Human metabolism is about twenty times lower.

At night, hummingbirds cannot feed and therefore cannot fuel that incredible metabolism, especially during periods in early spring when cold weather is coupled with few nectar-providing flowers. Instead, they have a remarkable adaptation called daily torpor, which is the equivalent of seasonal hibernation, a good example of the similarities that exist between daily cycles and seasonal ones. Both daily torpor and seasonal hibernation are controlled by biological clocks. During torpor, a bird’s fuel consumption drops, as measured by the amount of oxygen consumed for combustion, by about a hundred times. Then, just before dawn, its metabolism increases and its body temperature returns to normal as it arises, like Lazarus, from what seems to be a near-death state.

Daily Cycle of Sleep in Plants?

Plants don’t sleep—or do they? Most plants, just like animals, have circadian rhythms and make cyclic changes over the twenty-four-hour day. For example, most plants shut down their photosynthetic machinery or close their stomata, which are openings for gas exchange on their leaves, on a daily cycle. Because photosynthesis can occur only during daylight, the plant conserves energy by reducing its metabolism at night. Since both plants and animals conserve energy in this same way, most scientists concur that plants do, indeed, sleep, even though we more often associate sleeping with animals.

Some plants even undergo so-called sleep movements, a topic that so intrigued Charles Darwin that he devoted an entire chapter of his book The Power of Movement in Plants to the subject. Many species, especially those in the pea family, have circadian leaf movements, in which the normally horizontal leaves are folded vertically at night. If the plants are constrained so that they are unable to fold their leaves at night, then their growth rate declines. Mimosa (Figure 1-1), wood sorrels, and bean plants all exhibit sleep movements. Incidentally, the eastern sensitive-brier and other plants that fold their leaves in response to a physical disturbance, such as an animal brushing against them, use a similar mechanism to fold leaves, but the stimulus is physical, not circadian.

Communication at Night

Since we are primarily visual animals adapted for daylight, nighttime confronts us with challenges that can be downright scary. Vision, our major sense, is compromised by low levels of light. For nocturnal animals, nonvisual senses such as touch, hearing, and smell dominate sight in gathering information about the environment. You may have noticed in yourself a heightened sensitivity to sounds, odor, and touch during nighttime walks in field or forest. A gentle rustle of wind through leaves can sound like an elephant charging through underbrush; the delicate scent of flowers can be stronger than perfume; and the slightest breath of wind may stir the hairs on the back of your neck.

Most nocturnal organisms have well-developed senses of hearing and touch. Nighttime is full of booming frog voices, chirping crickets, buzzing katydids, whining mosquitoes, and the screams of bats (though unheard to us). These sounds, specific to each species, not only allow members to locate each other but also assist in selection of a mate. A female cricket is more impressed by a male that sounds good than one who looks good!

FIGURE 1-1

Mimosa (Albizia julibrissin) leaflets are open during the day (left) and closed at night.

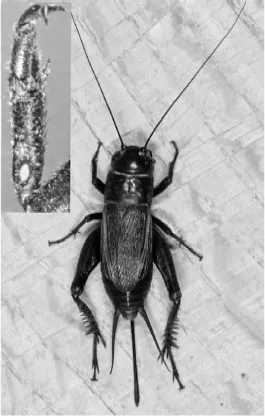

At its most simple, a hearing organ consists of a taut membrane stretched over a rim, like a drumhead. Physical disturbance of the air causes the drumhead (our eardrum) to vibrate, and those vibrations trigger nervous impulses that the brain interprets as sound. Each drumhead is called a tympanum, from the same word root as tympani, the drums of an orchestra. In frogs, which communicate with sound, the tympanums are large round disks, one located on each side of the head (Figure 1-2). Insects that communicate using sound may also have a pair of tympanums, but they are usually located on the legs (Figure 1-3). Other insects lack a tympanum but have specialized hairs that are tuned to vibrate at a particular pitch, like tuning forks. Male mosquitoes can recognize females of their species and some caterpillars can detect wasp predators because of sensory hairs that are tuned to the wing beat frequency of the female or the wasp, respectively. It must be an electrifying sensation as these surface hairs all buzz in response to an opportunity for either sex or predation! Echolocation is a specialized sense of hearing that has been well developed by bats (see chapter 4), and many of bats’ oddities are really just adaptations to this sense.

The senses of smell and taste are also well developed in nocturnal organisms. For instance, dogs have a much better sense of smell than humans and are a thousand times more sensitive to odors. While domestic dogs may not be primarily nocturnal, they are often active at night, as are wolves, coyotes, and foxes, their close relatives. Mammalian noses are particularly receptive to the molecule butyl mercaptan, which is found in mammalian sweat glands. A skunk’s attention-grabbing and enduring odor arises from a concentrated broth of butyl mercaptan that is produced from modified sweat glands (see chapter 5).

FIGURE 1-2

The wood frog (Rana sylvatica), like other frogs, possesses a tympanum or external eardrum, which is a circular disk just below and behind the eye. Unlike most other frogs, it lays its eggs in winter months.

The humid air of warm summer nights carries and disperses odor molecules more widely than the dry air of daytime, resulting in the nocturnal fragrances familiar to poets and lovers. Mammalian noses, however, are not the only organs that detect airborne chemicals. Snakes (see chapter 3) use their tongues to detect the chemical signals emanating from their prey. Each flicker of the tongue gathers odor molecules from the air and deposits them on a sensory organ in the roof of the mouth. Some insects, such as moths, use their antennae to detect odors, and males typically have larger antennae than females because males locate females by their subtle but alluring scent

FIGURE 1-3

This southeastern field cricket (Gryllus rubens) and other insects use a tympanum that is located on the tibia of each foreleg to transduce sound. The left front leg (inset) is magnified to show the tympanum, which appears as a light oval. This female cricket uses her long, thin ovipositor to deposit eggs deep into soil.

(see chapter 3). Insects also have chemical detectors on their legs. Houseflies, for example, taste food by walking on it.

Some nocturnal organisms rely on sight as their dominant sense and have adapted to the low light levels of night by improving their vision. As a general rule, these animals have large eyes that are extremely sensitive to light and often have a reflective layer. Many mammals that are active at night, such as opossums, have such sensitive eyes that the bright light of day disturbs them (see chapter 5). Some nocturnal animals, such as fireflies (see chapter 3), produce their own light and respond to particular patterns, colors, and frequencies of light emanating from other individuals.

Seasonal Cycles and Biological Calendars

The Southern Appalachian year is divided neatly into three months each of winter, spring, summer, and fall. December, January, and February make up winter; spring is composed of March, April, and May; summer has June, July, and August; and September, October, and November are fall months. Each season is long enough for us to experience its characteristic features of temperature, precipitation, day length, and the growth of plants and animals, but short enough for us to sense and appreciate the gradual change to the next season. Just as we begin to tire of winter’s cold, a gentle warm rain thaws the ground and releases wood frogs, a sure sign of spring’s approach (see chapter 5). Similarly, the fatiguing heat of late summer is soon relieved by the first returning cold front, as monarch butterflie...