![]()

ESSAY

“Redneck Woman” and the Gendered Poetics of Class Rebellion

Nadine Hubbs

In 2004 Gretchen Wilson exploded onto the country music scene with “Redneck Woman,” which became not only her signature song but her star persona. Redneck Woman was the tag line that served to introduce Wilson in public appearances and media features. The neck of her guitar even proclaimed “redneck” in mother of pearl inlay. Photograph courtesy of www.gretchenwilson.com.

In 2004 Gretchen Wilson exploded onto the country music scene with “Redneck Woman.” The blockbuster single led to the early release of her first CD, Here for the Party, and propelled it to triple platinum sales that year, the highest for a debut in any musical category. “Redneck Woman” shot to No. 1 faster than any country track in the previous decade and held the top spot for five weeks. Wilson garnered a raft of distinctions, including a Grammy for best country song and best female vocalist honors from both the Country Music and American Music Awards. (See the video at http://www.cmt.com/videos/gretchen-wilson/30774/redneck-woman.jhtml.)

The record was a milestone in country music and in the career of Wilson, who went in a few weeks from struggling Nashville unknown to top-selling Nashville star. In the process, the “Redneck Woman” she had created with co-writer and MuzikMafia crewmate John Rich became not only her signature song but her star persona. Redneck Woman was the tag line that served to introduce Wilson in public appearances and media features. The neck of her guitar even proclaimed “REDNECK” in mother of pearl inlay. More than a nickname, the handle keyed to a network of images, attributes, and attitudes that Wilson represented and that, for fans, represented her in an essential way. Loretta Lynn was the Coal Miner’s Daughter, Johnny Cash the Man in Black, and now Gretchen Wilson was the Redneck Woman. Anyone curious about the meaning of any of these monikers could simply listen to the eponymous song.

All three songs have served as identity totems for their singers and the fans who have embraced them. All are first-person narrations on themes that have been prevalent in postwar country music, including an identification with humble folk—both the materially impoverished and the socially scorned. “Coal Miner’s Daughter” (#1 1970) poignantly chronicles the singer’s hardscrabble family origins in a Kentucky holler. Its message is familiar to country fans: We were poor, but we had love—of God and each other.1 The narrator in “Man in Black” (#3 1971) explains that he shuns color in his dress to protest poverty, hopelessness, and lives lost to war and imprisonment. That song’s lyrics invoke another champion of the downtrodden, Jesus. The persona in “Redneck Woman” acknowledges her own scorned status but frames it with neither poignancy nor righteous protest. Her statement is a defiant apologia for herself and her redneck sisters and their “trashy” social position.

Wilson’s breakthrough single and its extraordinary reception remakes white working-class female identity through language, sound, and images and in relation to middle-class/working-class, male/female, and individual/communal affiliations. It is an identity bereft of cachet, or “cultural exchange-value,” according to Beverley Skeggs, a British sociologist whose work powerfully illuminates the cultural terrain on which the song is produced and received.

Skeggs offers a theory on the workings of the contemporary Western political and symbolic economy—a cultural system that elevates stories of individual “subjects” and rewards those who can access, use, and display the right identity attributes. The winners here are those who are positioned to access other subjects’ “properties.” These powerful actors can “use the classifications and characteristics of race, sexuality, class, and gender as resources” by borrowing them, fluidly and according to the circumstances, from the subject positions to which they are seen to belong. Such self-resourcing takes place in a modern neoliberal context of “propertized personhood.” Here, exchange-value attaches, not only to objects or the labor that transforms them into possessions (as in Marx), but to “the cultures, experiences, and affects of others” that entitled subjects use as resources for middle-class self-construction.

Less entitled subjects, however, are limited in their ability to trade and convert their characteristics and classifications “because they are positioned as those classifications and are fixed by them.” So, while the cool (among other characteristics) that attaches to black working-class males and the criminality that attaches to their white counterparts can be detached and deployed as resources by white middle-class men to enhance their cultural power, the source-subjects are pathologized and essentialized by their cool and criminality. In the workplace, straight male managers who perform feminine caring enhance their symbolic value and power, but women in the same role are essentialized, perceived as simply “being themselves,” and derive no special rewards. Indeed, they may be penalized for their (presumed) tendency to caring when toughness or another quality is called for. Certain selves are fixed in place so others can be mobile.2

An ethnographic study of white working-class women by Skeggs found the women’s position to be severely limited in this symbolic economy. They are inscribed with certain cultural dispositions, but none that inspire borrowing by others. Their subject-resources are assessed as fixed and worthless, having only use-value to themselves and no exchange-value in the cultural marketplace. Consequently, the women face restrictions on their economic value and their sense of individual value. Skeggs writes of her research subjects that a “daily struggle for value was central to their ability to operate in the world and their sense of subjectivity and self-worth.”3 Her analysis offers a frame for understanding the phenomenal popularity of “Redneck Woman,” particularly among fans its chorus calls out as “redneck girls” (“Let me get a big hell yeah from the redneck girls like me”).

The record uses self-resourcing techniques and song craft to affirm the distinctiveness and legitimacy of the Redneck Woman, and does so in solidarity with redneck men. Indeed, the track trades on the only exchange-value Skeggs locates in white working-class identity, male criminality, through allusions to hardcore rock and country icons. “Redneck Woman” positions itself on the “hard” side of a hard/soft duality identified by sociologist Richard Peterson as a perennial dialectic in commercial country music, with gendered roots in earlier male public instrumental (barn dance) performance and female domestic vocal (parlor) performance, respectively. The song invites comparison with postwar hard country, which literary and cultural critic Barbara Ching analyzes as a “burlesque abjection” of culturally low, ineffectual white masculinity defiantly enacted against the foil of “women and conventionally successful men.”4

“Redneck Woman” is also defiant but directs its defiance exclusively at the dominant middle-class culture. It offers moments of burlesque in lyrics touting the narrator’s unrepentant year-round Christmas displays, barefoot baby-toting, and preference for cheap Walmart lingerie. But it stakes serious claims for her resourcefulness, country affiliations and tastes, desirability, and, especially, agency. Indeed, the song de-essentializes and thus remakes a subjectivity long disowned and devalued in the dominant culture and once labeled the “Virile Female”—by proclaiming it deliberately chosen. This remaking calls upon popular music’s capacity to model and create social identity.5 And it begins at the song’s title, with its juxtaposition of clashing identities.

FRAMING THE REDNECK

The first of these identities, “redneck,” is conspicuously classed, but its working-class valence is also marked in terms of race—white; locale—provincial; and sex—the “redneck” label conventionally attaching to maleness and connoting a rough style of masculinity, often, but not exclusively, southern.6

Several scholars have noted the emergence in the 1970s of a “redneck pride” phenomenon in the United States, with roots in country music. Peterson documents an early redneck pride moment beginning in 1973, and involving a spate of country songs over the next few years, that helped to redefine the word redneck and make it into a label voluntarily claimed and positively associated with “an anti-bourgeois attitude and lifestyle.” Country music historian Bill Malone sees in Jimmy Carter’s 1976 election the dawn of a more “benign” view of the South, accompanied by a shift in meanings: “‘Redneck’ seemed somehow to be overcoming the association with racial bigotry from which it suffered in the early 1960s, and instead was now being used to describe white working-class males. It became a proud self-designation for many white southerners and by the early eighties was appearing frequently in country songs.” In fact, these changes extended beyond the South, at the least to the industrial Midwest and other destinations of the many white southerners who migrated north in the twentieth century. Thus cultural anthropologist John Hartigan notes in connection with his ethnographic work in Detroit that by the late 1980s terms like redneck, hillbilly, and country boy were claimed with pride and used almost interchangeably to connote “working-class lifestyle and consciousness.”7

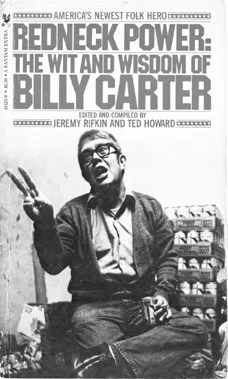

Bill Malone sees in Jimmy Carter’s 1976 election the dawn of a more “benign” view of the South, accompanied by a shift in meanings: “‘Redneck’ seemed somehow to be overcoming the association with racial bigotry from which it suffered in the early 1960s, and instead was now being used to describe white working-class males. It became a proud self-designation for many white southerners,” including “America’s Newest Folk Hero” Billy Carter, who enthusiastically promoted “redneck power” during his brother’s presidential campaign. Courtesy of Bantam Books, 1977.

By the early 1990s the comedian Jeff Foxworthy had taken up the torch of redneck pride. Foxworthy launched a thriving redneck comedy industry in U.S. popular culture and in 2000 with three fellow comedians brought the phenomenon to its apex in the Blue Collar Comedy Tour. At the core of Foxworthy’s franchise is an ever-growing list of jokes in the form, “If ——, you might be a redneck.” In live performance Foxworthy’s redneck-revealer lines elicit enthusiastic response from his nearly all-white audience, who appear to be, like Foxworthy himself, at least once removed from redneck identity. His stand-up comedy expanded the visibility of redneck reclamation and advanced a commercial and cultural redneck pride movement that inspired identification, however ironic, with a persona elsewhere despised and unfashionable.

Foxworthy and company’s runaway popularity lent “redneck” a brand currency that undoubtedly helped set the stage for “Redneck Woman.” Here, however, redneck identity was decidedly male. All four comedians on the 2000 Blue Collar tour were male, and their humor centered on a male redneck subject. Foxworthy’s “you might be a redneck” gags often hinge on a reference to “the redneck”’s wife or girlfriend or otherwise conjure a male subject implicitly via compulsory heterosexuality (“If you go to the family reunion to meet women, you might be a redneck”). The redneck’s maleness is also explicit in the Carter-era context described by Malone and in some late–twentieth-century literary examples given in the Oxford English Dictionary under the term redneck:

Prior to the 2004 release of “Redneck Woman,” a turn-of-the-millennium redneck craze had brought to a head three decades of redneck pride. It created an audience for representations of redneck identity perceived as funny or telling while retrenching its male image. Gender is thus foregrounded in “Redneck Woman” beginning at the title, where cross-paired identities create a stereotype-jolting effect like that of “female surgeon” or “lady plumber.” Here begins too the foregrounding of class, and its entanglement with gender. Listeners are likely to be drawn into “Redneck Woman” by the implications of the title, including the implication that the song might shed some light on its gender-and class-freighted contradictions. And it does, through both music and lyrics, in ways that we will examine in some detail. Before opening that examination involving interlinked issues of gender, class, and country music, it will be useful to engage some existing dialogues around and within these three domains, as found in scholarship and in country songs themselves.

CLASS (UN)CONSCIOUSNESS AND COUNTRY MUSIC

Denial of class difference runs high in American society. Several decades’ sociological research has documented a tendency “for all but the very rich and very poor to define themselves as middle class.”8 The cultural anthropologist Sherry Ortner traces the emergence of this tendency to a postwar “national project” she calls the “middle-classing of (white) America.” Directed at improving working-class minds, skills, and consumerism through the G.I. Bill and other programs, its rationales included defense of capitalism against communist encroachment, defense (in the wake of Nazism) of the populace against ideological vulnerability, and deflection of “the class consciousness and incipient class warfare” that had arisen during the Great Depression.

Results of this middle-classing project included “obscuring the older middle class/working-class boundary, especially among white people” and the transformation of class, with its linkages to communism, into “a kind of dirty word.” Within the national discourse, Ortner notes, the class boundary was “largely replaced with a race boundary; and everyone white—with a few virtually invisible ‘exceptions’ at both ends—became, or imagined themselves to have become, middle class.” One might add that race and class became conflated, such that people of color were assumed to be poor and working class, and white people middle and upper class.9 These notions persist in the United States generally. But should we not expect things to be different in country music, given its legendary links to the white working class?

Peterson addressed this question in his 1992 essay “Class Unconsciousness in Country Music.” He contends that country music engages with and celebrates working-class topics but does so, across all its thematic genres, in a way that is politically regressive and fosters “class unconsciousness.” Describing the latter as a “fatalistic state in which people bemoan their fate, yet accept it,” Peterson echoes countless critiques of country m...