eBook - ePub

Living with Spina Bifida

A Guide for Families and Professionals

- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Living with Spina Bifida

A Guide for Families and Professionals

About this book

It is the most common complex birth defect. Spina bifida affects approximately one out of every 1,000 children born in the United States. In this comprehensive guide, Dr. Adrian Sandler offers a wealth of useful information on the medical, developmental, and psychological aspects of this condition.

Accurate, accessible, and up-to-date, Living with Spina Bifida is written especially for families and professionals who care for children, adolescents, and adults with spina bifida. This edition contains a new preface by the author, addressing recent developments in research and treatment, as well as an updated list of spina bifida associations.

Accurate, accessible, and up-to-date, Living with Spina Bifida is written especially for families and professionals who care for children, adolescents, and adults with spina bifida. This edition contains a new preface by the author, addressing recent developments in research and treatment, as well as an updated list of spina bifida associations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Living with Spina Bifida by Adrian Sandler, M.D.,Adrian Sandler M.D. in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Diseases & Allergies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

A Holistic Overview of Spina Bifida

A BRIEF CLINICAL DESCRIPTION

“Spina bifida” means a split or divided spine. It is a birth defect that occurs within the first month of pregnancy, when the embryo is about the length of a grain of rice. The cause of spina bifida is not known with certainty, but it is likely that folic acid deficiency during the crucial early weeks of pregnancy sometimes contributes to the problem.

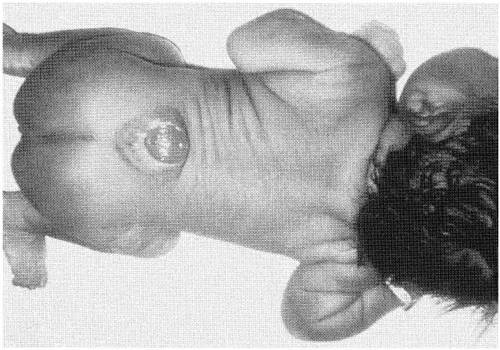

The defect in the spine may occur anywhere along the spinal column but is usually found in the midback (thoracic), in the lower back (lumbar), or at the base of the spine (sacral). Spina bifida may be open or closed. Closed spina bifida, or “spina bifida occulta,” is a fairly common condition in which the bones of the spine may be incomplete, but the defect is covered by skin and the spinal cord is usually normal. Most people with spina bifida occulta have no symptoms or clinical problems. Usually the term “spina bifida” is reserved for an open defect of the spine, in which the spinal cord does not form properly and is exposed (Figure 1.1). Another commonly used term for this condition is “myelomeningocele,” in which there is generally some degree of paralysis of the muscles in the leg. If the defect is in the high-lumbar or thoracic region, there may be few functioning leg muscles, whereas lower defects may result in lesser degrees of paralysis. The nonfunctioning part of the spine may also cause loss of sensation in the legs and may give rise to orthopedic deformities. There is often some interference with normal bladder and bowel control. The clinical problems associated with spina bifida are described more fully in Chapter 2.

Most babies born with spina bifida also develop excess fluid in the ventricles (fluid spaces) in the brain. This problem is known as hydrocephalus and is typically treated in the newborn period with the placement of a shunt to drain the excess fluid. Hydrocephalus and its treatment are discussed in more depth in Chapter 5.

Figure 1.1. Spina bifida: a newborn infant with a midlumbar, open myelomeningocele

A DEVELOPMENTAL PERSPECTIVE

As I write this brief overview of spina bifida, I am working as camp doctor at a summer camp for children with this condition. Watching these youngsters playing and having fun, I see enormous variation in development. The outlook for the individual child is hard, if not impossible, to predict with any accuracy. A child’s development unfolds in unique ways. Although our genetic makeup powerfully influences our development, environmental forces are equally critical. The destiny of the individual is therefore a product of both “nature” and “nurture” and the interplay between these two. A combination of good genes, a supportive family, and a facilitating environment can enable an individual to find ways around the physical limitations imposed by the presence of a birth defect.

Another important principle of development is that it does not occur smoothly but rather in fits and starts, with sudden growth periods and other quiet plateaus. Furthermore, the demands are continually changing. So it is that a child may have successfully met the demands and challenges of preschool and kindergarten but now begins to show learning problems in early elementary school. These problems do not truly arise out of the blue but were not evident in earlier years because the demands and expectations then were different from those now.

The key to maximizing developmental outcomes and fulfilling potential is to emphasize strengths and to build on them. Think “abilities,” not disabilities, and focus on the strengths rather than the deficits. To put this principle into practice, professionals and families must work together as an effective partnership.

Studies that have followed large numbers of children with spina bifida into adulthood show many reasons to feel optimistic. For example, in Dr. D. G. McLone’s study (McLone 1989), 85 to 90 percent of babies with spina bifida survived into adulthood, 70 to 80 percent had normal IQ scores, 80 percent were socially continent, and fully 75 percent were in competitive employment. These favorable statistics reflect advances in and a more aggressive, comprehensive approach toward treatment over the past fifteen years or so. Many adults with spina bifida did not have the benefit of such treatment approaches, however. This is reflected in the less favorable results of other follow-up studies. For example, Dr. Gillian Hunt (1990) published a study of young adults in the United Kingdom, showing a survival rate of 59 percent. Sixty-eight percent of her series had IQ scores of 80 or above, 52 percent were independent, 25 percent were continent, and only 25 percent were in competitive employment.

Promoting good health and optimal development is the most important challenge for people with spina bifida and their families. For all people with disabilities, prevention of further disability from secondary conditions is the key to meeting this challenge. Secondary conditions may include contractures of the joints, depression, obesity, and skin breakdown. Prevention of secondary conditions involves the elimination of risk factors for further deterioration; such prevention activities may depend on changing the individual’s behavior, aspects of the environment, or both. This is the joint responsibility of the family and the health care providers. In this country and elsewhere, there is growing recognition of the critical importance of preventing secondary disability. Above all else, it is these activities that really make a difference over the life span of those with disabilities. The Disabilities Prevention Program of the Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta is especially interested in this issue, and the Americans with Disabilities Act (discussed in more depth in Chapter 11) has added additional impetus. These themes of health promotion, prevention of secondary disabilities, and the maximizing of developmental outcomes are stressed throughout this book. In later chapters we shall explore these themes as we consider spina bifida through the life span: how to promote good health, to prevent problems, and to improve quality of life at different ages. First, it is essential to define some important terms and discuss a framework for understanding disability. This framework is based on the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities, and Handicaps (1980).

Loss of sensation

Paralysis of muscle groups

Problems with bladder, bowel, and sexual function

Learning and developmental problems

Orthopedic problems

Figure 1.2. Impairments that commonly (but not always) occur in spina bifida

IMPAIRMENTS, DISABILITIES, AND HANDICAPS

The main impairments of spina bifida are the sensory and motor impairments discussed above. In addition, there may be subtle cognitive impairments related to changes that occur in the developing baby’s brain. These and other impairments of spina bifida are shown in Figure 1.2.

When an impairment significantly interferes with one or more major life activities of an individual, a disability can be said to exist. Not every impairment construes a disability. One can be extraordinarily tone-deaf and have a severe impairment in music appreciation, for example, yet one would hardly be described as music disabled! The key issue is the extent to which an impairment interferes with functional activities. The impact of an impairment on day-to-day function may be decreased by technology, equipment, and good ideas. Velcro has dramatically decreased the fine-motor disabilities of millions of people, for instance.

Disabilities are lifelong, although their relative importance and their impacts may change over time. A learning disability, for example, may be extremely evident in school, where academic demands are ever present, but an adult with a learning disability may choose an occupation that plays to his or her strengths, thus allowing progress and productivity. Choices, compromises, and adaptations enable an individual to live with a disability and rise above it.

“Handicap” is a term that is out of favor in this country. When a disability runs headlong into a barrier imposed by the environment, that is a handicap. Using a wheelchair is a handicap if there are no access ramps or if you can’t use public transport. We cannot pretend that handicaps do not exist, but they exist largely in the realm of the environment, not in the person with a disability. By removing the barriers, be they physical or attitudinal, we remove the handicaps.

For individuals with spina bifida, a disability of locomotion is often the first to become evident. Spinal level and muscle strength are the most important determinants of a young child’s readiness to walk. Toddlers with low-lumbar spina bifida may progress easily from reciprocal crawling to standing and may start to walk with only minimal bracing around the ankles. Those with higher lesions will need more extensive bracing to promote walking. Children are naturally motivated to be upright and ambulatory, and there are physical and psychological benefits to being up and walking, even if the bracing needs, gait training, and orthopedic procedures are extensive. For many children with midlumbar-level spina bifida or above, however, continued ambulation becomes impractical. Getting in and out of long leg braces can be time consuming, and the process of walking, extremely tiring. Many find a greater ease and efficiency in the use of wheelchairs, and as more and more places become wheelchair accessible, this option needs to be considered. Different kinds of braces and patterns of ambulation will be discussed in Chapter 6. The point here is that many youngsters may feel less disabled in a chair than in long leg braces.

Many young children with spina bifida and hydrocephalus have an impairment of fine-motor coordination. They may be less likely to explore toys with their hands and to manipulate objects with dexterity. Because the active exploration of the environment is an important precursor of learning in infancy, some of these children may be delayed in their acquisition of key visual-spatial concepts. It is not altogether surprising that many of these children struggle in mathematics and other aspects of learning in later years. I have also seen many children with spina bifida who lack the manual dexterity and eye-hand coordination to manage crucial challenges of self-care successfully, such as toileting and self-catheterization. In this way, a common impairment in spina bifida may give rise to a disability affecting learning and/or self-care. Generalized disability in learning and self-care is sometimes called “developmental disability.”

The key to minimizing developmental disability is to maximize independence and self-care. Independence and self-care skills are acquired in sequence, in a step-by-step fashion. This is why it is so important to stimulate these fine-motor and adaptive skills early on. I strongly urge parents to encourage their infants to explore the world around them. It is important to overcome our natural parental tendencies to be overprotective of infants and toddlers with spina bifida, to let the little ones learn through doing, even if they have to work very hard in the process. It is through doing, through exploring, that we learn about cause and effect and develop our internal motivation. Early developmental intervention, involving parents and therapists, is the key to decreasing the developmental disability in spina bifida.

I have made an effort in this chapter to distinguish impairments, disabilities, and handicaps because these crucial distinctions need to be made for a child to fulfill his or her potential. Parents, teachers, and health care professionals alike must strive to remember that impairments need not necessarily become disabilities, and disabilities should never become handicaps.

At this point, I shall hand over the “pen” to people who really know what they are writing about! The first is an account of a young child, written by his mother. The second is an autobiographical note from an adult woman, who describes some of her firsthand experience of having spina bifida.

THE STORY OF A CHILD

My name is Kim. I am twenty-seven years old. My son Sam was born in May 1992 with spina bifida.

I first found out there was possibly a problem with my pregnancy at fifteen weeks when I had the AFP (alpha-fetoprotein) test done. This was my second child, and when they asked if I wanted the AFP test done, I still didn’t know exactly what it was but remembered I had had it done when I was pregnant with my daughter. I remember my obstetrician telling me it had something to do with Down syndrome. So I decided I might as well have it done. I didn’t give it much more thought. That is, until the day my obstetrician called me at work and told me my AFP had come back slightly elevated. “My what? Is what? What does that mean? Is my baby going to be all right?” My heart jumped to my throat, I could feel my pulse racing, I felt nauseous, and the tears started pouring. I had so many questions, and I was scared to death. I immediately made an appointment to have an ultrasound done in Chapel Hill. I then left work. I just had to!

Immediately, I began collecting information on the AFP test. By the next day I felt much better because I had read that only one or two out of every fifty women who have an initial high reading will have an affected fetus. This could never happen to me! On the day my husband Michael and I went to Chapel Hill for the ultrasound, I was a little nervous, but I just knew everything was going to be fine after all.

First, we had the counselor talk to us about spina bifida. She asked a few questions about our medical history. She helped us to understand what was going on and what to expect if the ultrasound did show a problem.

Now came time for the ultrasound. Almost immediately, the technician saw “something suspicious.” Then the tears started flowing again. She went to get the doctor. Dr. Cheschier came in, looked at the ultrasound, and began explaining what she saw. I can’t remember all that was said. I still couldn’t believe this was happening to me.

After the ultrasound, Dr. Cheschier, Michael, and I went into her office and began discussing Sam’s condition. The one good thing that came out of this day was that we found out that we were having a boy. From that day on the baby wasn’t a fetus or an “it”; he was Sam.

The next step was to have an amniocentesis done. This was to make sure there were no other problems. The amnio confirmed spina bifida, but there were no other concerns.

Now the subject of terminating the pregnancy came up. Well, for me, I never had to think twice about it. I knew I wanted to keep Sam. Something deep inside of me kept telling me I was making the right decision. If the prognosis for Sam had been worse, if there had been other problems, I don’t know that I would have made the same choice. I just knew that this was the right choice for me. As for my husband, who is Catholic, abortion was never even a possibility. And as for my family and friends, my decision to continue the pregnancy was questioned by them. I know in my heart their main concern was me. I remember several arguments with one of my best friends. She wanted to know what I was going to tell him when he asked why he couldn’t run and play like all the other kids. How do you answer a question like that? I couldn’t predict the future. I couldn’t explain to people the calming feeling I had, knowing God would never put more on me than I could handle. This experience truly brought out my faith in God. I did a lot of praying.

For the next five months, my life revolved around doctor’s appointments, gathering every bit of information I could find about spina bifida, working full time, spending every moment I could with my daughter, buying a house, keeping my sanity, being optimistic, and keeping a smile on my face. I had meetings with all the specialists. I remember meeting with Dr. Sandler, asking him a thousand questions, and wishing he had a crystal ball so he could answer them. Will Sam be able to walk, to play sports, to go to the bathroom, to have girlfriends, to go to college, to get married, to have a family? No one knew the answers.

As time went on, Sam’s prognosis did seem to improve. The opening in Sam’s spine was very low and small. I was told he could quite possibly have to use a wheelchair but that there was a good chance he would walk with leg braces. As far as the fluid developing in his head, I read that 90 percent of children develop hydrocephalus. We kept waiting for bad news, but Sam never developed it.

Then Sam was born May 6, 1992, at 10:00 A.M., in Chapel Hill. Sam weighed eight pounds, thirteen ounces, and was twenty inches long. He was beautiful!

Yes, he did have an opening in his spine, and he had to have surgery within the first few hours of his life. The operation went well. Sam was out of surgery in about three hours and went to the neonatal intensive care unit. I asked the doctors if Sam would be able to go home with me. Dr. Sandler said it was highly unlikely that a baby born with spina bifida would go home at the same time as the mother. Well, not only did Sam go home with me, he was in the ICU for only two days before he was moved to the regular nursery (although I kept him rooming in with me most of the time)!

Sam is now eighteen months old. He is walking, running, climbing, dancing, just like any other eighteen-month-old child. He did not develop hydrocephalus, and so he never had to have a shunt. Sam is unquestionably a miracle baby, and I know the chances of a child with spina bifida turning out to be this healthy are slim, but it happened. I don’t regret any part of the experience I had. Some people think I would have been better off not knowing about the spina bifida, especially since he turned out to be so healthy. I don’t agree. Because I was informed of the possibilities, I was able to give Sam the best care possible. I had the best doctors, the most advanced equipment, and was able to prepare myself mentally.

It was a miracle that Sam turned out the way he did, but if he had not I would have been ready. I can’t begin to imagine what it would have been like if I had not known there were any problems until after he was born. I knew in advance that I would not be able to hold him immediately, and that was one of the hardest things to accept. However, I was able to prepare myself for that. Also, if I had not been informed of the situation in advance, as soon as Sam was born the doctors would have seen the hole, they would not have let me hold him, and I would have had no idea what was going on. Knowing how overwhelming that natural instinct is to want to hold your baby, well, I can’t even begin to imagine the pain and terror ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Living with Spina Bifida

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Glossary

- Chapter 1 A Holistic Overview of Spina Bifida

- Chapter 2 Neural Tube Defects

- Chapter 3 Epidemiology of Spina Bifida

- Chapter 4 Pregnancy and Childbirth

- Chapter 5 The Newborn Baby

- Chapter 6 Infants and Toddlers

- Chapter 7 Preschoolers

- Chapter 8 The School-Age Child

- Chapter 9 The Adolescent and Young Adult

- Chapter 10 Focus on the Family

- Chapter 11 Focus on Education and Work

- Appendix Directory of Spina Bifida Associations

- References and Suggestions for Further Reading

- Index