eBook - ePub

An Example for All the Land

Emancipation and the Struggle over Equality in Washington, D.C.

- 376 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

An Example for All the Land

Emancipation and the Struggle over Equality in Washington, D.C.

About this book

An Example for All the Land reveals Washington, D.C. as a laboratory for social policy in the era of emancipation and the Civil War. In this panoramic study, Kate Masur provides a nuanced account of African Americans' grassroots activism, municipal politics, and the U.S. Congress. She tells the provocative story of how black men’s right to vote transformed local affairs, and how, in short order, city reformers made that right virtually meaningless. Bringing the question of equality to the forefront of Reconstruction scholarship, this widely praised study explores how concerns about public and private space, civilization, and dependency informed the period’s debate over rights and citizenship.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access An Example for All the Land by Kate Masur in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Everywhere Is Freedom and Everybody Free

THE CAPITAL TRANSFORMED

On Thursday, August 14, 1862, an extraordinary meeting convened in Washington's Union Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church in downtown Washington. The previous Sunday, President Abraham Lincoln, through a representative, had put out word that he wanted to meet with a small group of black Washingtonians. Amid great excitement and curiosity about the purpose of the meeting, African American church congregations selected delegations to convene at Union Bethel days later. Going into the meeting, attendees were unsure what the president wished to discuss or even whether he would be present.

Lincoln was not in Union Bethel that day. It fell to his representative, James Mitchell, a white minister from Indiana, to inform the group that the president wanted to discuss African American emigration out of the United States. Like many other Americans, Lincoln was pessimistic that black and white people could live together peacefully under conditions of equality, and he had long seen black emigration as a potential solution to that problem. In the preceding months, the federal government had begun to lean toward colonization as policy. Congress had placed $600,000 at Lincoln's disposal for settling newly freed African Americans outside the United States, of which $100,000 was earmarked for residents of the capital. James Mitchell's announcement in Union Bethel suggested that the president was ready to begin spending that money.

The historic implications of the invitation itself were clear. In the midst of a civil war capable of destroying slavery, Lincoln's request implicitly recognized African Americans as a part of the American public to be consulted, not simply acted upon. Yet those who assembled in Union Bethel had grave doubts about the president's purposes, and many were reluctant to comply with his request. First, they were skeptical about the government's turn to colonization as policy. They questioned the origins and credibility of Lincoln's proposal “to a great length.” Was this the “voluntary action of the President, or forced upon his consideration by the selfish interest of non-resident parties?” they wondered. Some were also uncomfortable at the prospect of a small delegation being asked to represent the views of all the black residents of the capital, or perhaps even the nation. One attendee “did not feel authorized to commit our people to any measure of colonization.”1

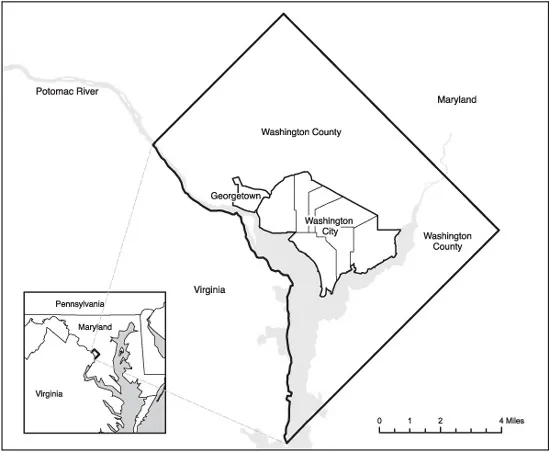

MAP 1. THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

Mitchell attempted to reassure, and after much debate the assembled group decided to send a delegation to Lincoln. First, however, Edward M. Thomas and John F. Cook Jr. proposed two resolutions that would register the group's objections. The first declared it “inexpedient, inauspicious, and impolitic” to advocate emigration out of the United States and suggested “that time, the great arbiter of events and movements, will adjust the matter.” In other words, with the war on, they thought it best to wait and see what would happen. The second resolution questioned the propriety of a small group of people presuming to represent all black Americans, stating that it was “unauthorized and unjust for us to compromise the interests of over four-and-a-half millions of our race by precipitate action on our part.”2 The Union Bethel meeting adopted the resolutions. Thus having rejected the very premises of the conversation Lincoln hoped to initiate, the five-man delegation, which included Cook and Thomas, left with Mitchell for the Executive Mansion.

Abraham Lincoln's August 1862 meeting with a delegation of African American men is well known to students of the Civil War, but the broader local context for that meeting has been largely forgotten. Historical literature on the capital during the war has focused on military defense and intrigue in the federal government but has paid little attention to the unfolding of emancipation and to the debates about racial equality that also occupied local residents, congressmen, and the president of the United States.3 In fact, by the summer of 1862, when Lincoln invited the black delegation to meet with him, the debate about racial equality in the national capital was already well under way. That spring, Congress had passed legislation, beginning with an Emancipation Act for the District of Columbia, to implement the Republican vision of basic racial equality before the law. Yet black Washingtonians were pushing the struggle for equality further than Congress originally intended to go.

As policy makers debated whether a war for union should become a war for emancipation, thousands of fugitives from slavery migrated into the city in search of freedom, safety, and employment. Crowds gathered in the streets and at the courthouse to insist that officials cease to enforce fugitive slave laws in the Union capital. Members of the long-standing black elite mobilized to aid and uplift the destitute and to shape the public debate, which in 1862 was centrally concerned with whether to emigrate out of the United States rather than risk an uncertain future at home. Local African American debate about emigration, which began before the Lincoln delegation and persisted after it, revealed divisions among black Washingtonians not only about emigration itself but also about who could represent whom and whether it was important for African Americans to be united on the crucial issues of the day.

By 1863, however, the federal government's turn toward a policy of emancipation provided an impetus for bolder demands at home. Black soldiers, enlisted late that spring, rejected conventions of racial deference and demanded, instead, to be respected on the streets and to ride the city's newly established streetcars as equals to white men. By the summer, African Americans were insisting, through public demonstrations by the citywide Sabbath school movement and benevolent associations, that freedom must mean full citizenship in the community. African Americans combated inequality not only by demanding rights but also by insisting on equal privileges and equal status in local life. Their agenda, the willingness of some in Congress to take up their cause, and white Washingtonians’ almost unmitigated hostility, all laid the groundwork for the protracted struggles of Reconstruction.

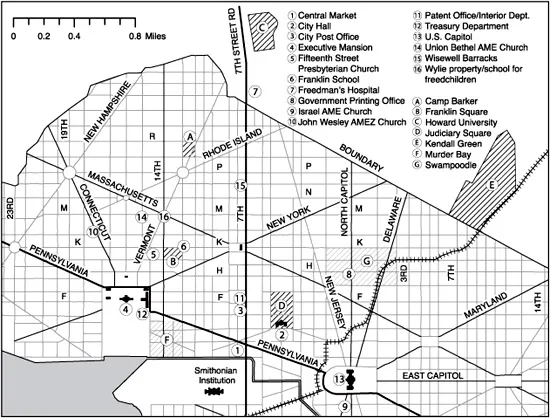

MAP 2. LANDMARKS IN CENTRAL AND NORTHWEST WASHINGTON CITY

The Combination Yet Wanting

When Charles Dickens visited Washington in 1842, he called the capital “the City of Magnificent Intentions” and ridiculed its “spacious avenues, that begin in nothing, and lead nowhere.” Beginning with its emergence from the Constitutional Convention of 1787, the nation's capital was a contradictory mix of planning and spontaneity, grandiose dreams and more mundane realities. Delegates to the convention purposely gave the capital its own territory, apart from the states, to avoid fueling jealousies among states or subjecting the federal government to the influence of a single state. And the capital, not being a state, had no representatives in Congress. The first Congress determined in 1790 that the new capital city would be located on the banks of the Potomac River, and, while president, George Washington sited the city where the river forked just below the Great Falls of the Potomac. Washington City thus joined the existing towns of Georgetown and Alexandria within the confines of a federal district carved from land donated by Virginia and Maryland. The rural area surrounding the three cities was designated Washington County. The federal government began moving to the unfinished city in June 1800, and Congress first convened there that fall.4

President Washington and his engineers envisioned a regal capital of wide boulevards and imposing public architecture that would become a commercial hub and a civic beacon. Yet, in a new nation where many people held a deep suspicion of centralized government, ideological predispositions and conflicts over spending priorities meant that federal authorities never appropriated enough money to build the monumental capital that its planners had envisioned. Nor did the capital become the commercial center that George Washington had imagined. It lagged behind the vibrant port city of Baltimore, fifty miles away, and did not become a gateway to the West as its boosters had hoped.5 In the midst of the Civil War, the poet Walt Whitman described the ironies and unevenness of the capital's development as a metaphor for the nation as a whole: “The city, the spaces, buildings, &c make no unfit emblem of our country, so far, so broadly planned, every thing in plenty, money & materials staggering with plenty, but the fruit of the plans, the knit, the combination yet wanting.”6

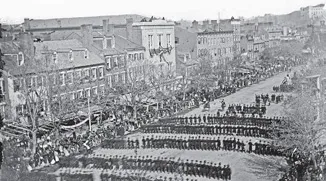

The contradictions of quotidian life in the antebellum capital were nowhere clearer than on the busy strip of Pennsylvania Avenue between the Executive Mansion and the Capitol. Designed as a grand artery and the symbolic link between the executive and legislative branches of the federal government, “the Avenue” was wide and regal, and from early on Washington's socially conscious made it a place to see and be seen. Yet even on the Avenue, tawdriness converged with grandiosity. Well-dressed women and men mingled with shoe shiners and newspaper boys, fancy carriages shared the street with decrepit hacks, and expensive boutiques stood near the city's cacophonous central market. The south side of the street hosted a hodgepodge of businesses and residences, many of them considered disreputable. That side also ran close to the city's putrid canal, essentially an open sewer running through the heart of the city. The adjacent slum was known as Murder Bay. Ever conscious of the implications of spatial mingling and contamination—perhaps both literal and figurative—the promenading elite shunned the south side of the Avenue, confining its self-conscious rituals to the north side.7

FIGURE 1.1. This photograph of Abraham Lincoln's funeral procession shows the scale and style of buildings on the north side of Pennsylvania Avenue. Courtesy Library of Congress, LC-DIG-cwpb-00593.

The capital's governing structures mingled federal authority with municipal regulation. The Constitution gave Congress power “to exercise exclusive Legislation” in the District, but from almost the beginning Congress delegated some governing responsibilities to municipal governments within the capital. Washington's original charter provided only for a mayor appointed by Congress, but an 1820 charter established a bicameral legislature (a board of aldermen and a common council) and a popularly elected mayor. At first, the privilege of voting was limited to white men with $100 or more of property, but in 1848 the property requirement was dropped. Congress also granted Georgetown a municipal charter, and Washington County was governed by an appointed body called the Levy Court. Congress returned Alexandria and the Virginia portion of the capital to the state of Virginia in 1846, and from then on the District of Columbia contained three separate local jurisdictions—Washington City, Georgetown, and Washington County—over all of which Congress had ultimate power.8

Despite its uniqueness as the nation's capital, however, Washington was in many respects similar to other midsize cities of its era. This was a period of rapid urbanization throughout the nation, and Washington shared in that trend. As in other cities, boosters and businessmen advocated grading and paving of streets and turnpikes, improved railroad links with other cities, drainage of polluted waterways, and better policing. And as elsewhere, the municipal government sought to raise money by taxing real estate and other property and by issuing bonds. In Washington, improvements did not keep pace with the needs of the growing population, but the same was true in cities throughout the country, which also struggled to finance basic infrastructure. Still, improvement-minded residents of the capital were quick to blame the federal government itself for holding the city back. The government paid no taxes on property, and the nation's legislators took little interest in local urban development, except to the extent that it improved their own lives. Indeed, in the antebellum years, the federal government extended the Capitol, built a water supply system (oriented toward federal offices, not District residents), and paved the Avenue.9

Slavery and its legal and cultural trappings were integral to the antebellum capital. Free and enslaved black workers worked alongside white men in building such national monuments as the Capitol and the Executive Mansion, and black laborers filled myriad positions typical of the urban South: domestic workers, skilled craftsmen, laundresses, and day laborers.10 During the antebellum years, Washington's black population grew steadily, while the proportion of slaves to free blacks diminished. In 1860, 78 percent of the local black population was free, up from 73 percent ten years earlier. Yet, even as increasing numbers of black Washingtonians enjoyed nominal freedom, the threat of sale hung over everyone. The decline of slavery in the Chesapeake region generated a thriving business of selling slaves to the booming Southwest. Enslaved people were always at risk of being sold away, while their free counterparts were threatened with kidnapping. As historian Stanley Harrold put it, slavery in antebellum Washington was “both weak and vicious.”11

Federal and local officials worked together to secure both slavery and the racist legal order that supported it. During the 1830s, for example, proslavery congressmen countered abolitionists’ demand for emancipation in the capital with a gag rule that prohibited Congress from receiving antislavery petitions. In the Compromise of 1850, antislavery legislators managed to ban the slave trade in the District, yet slavery itself continued on, protected by the good graces of Congress.12 Meanwhile, Congress gradually augmented the powers of the Washington city government, and the city government in turn passed black codes designed to circumscribe the activities of free blacks. In 1820, the municipal government enacted laws requiring free blacks to obtain signatures and peace bonds from prominent whites who vouched for their continued good behavior. Later laws established curfews for African Americans, banned them from certain lines of work, and forbade them from holding meetings without a permit from city officials. In a sign of the intent to reduce the presence of black people in Washington's official public spaces, Congress in 1828 instructed the federal commissioner of public buildings to bar African Americans from the Capitol grounds except when there on “business.”13 Some of the black codes were enforced sporadically, but the threat of enforcement always loomed, particularly in times of heightened racial tension. After an 1848 attempt by dozens of slaves to escape on the schooner Pearl, for example, Georgetown and Washington officials petitioned Congress for broadened police powers to prevent slave escapes and to tighten controls over free blacks. Washington City soon more than doubled its police force and created a requirement that free blacks purchase $50.00 certificates of their free status and carry them at all times.14

Free black Washingtonians faced not only legal restrictions on their lives and livelihoods but also discrimination in the labor market and by white laborers and trade unions. Growing numbers of European immigrants put pressure on the labor market for both skilled and unskilled jobs, intensifying racial tensions among laboring people. For instance, in 1852 a group of 250 white laborers petitioned Con...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- An Example for All the Land

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures and Maps

- Introduction

- 1 Everywhere Is Freedom and Everybody Free

- 2 They Feel It Is Their Right

- 3 Someone Must Lead the Way

- 4 First among Them Is the Right of Suffrage

- 5 Make Haste Slowly

- 6 To Save the Common Property and Respectability of All

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Works Cited

- Acknowledgments

- Index