![]()

Chapter One

Los Orígenes Mallorquines

Eduardo Bonnín Aguiló and the Birth of the Cursillo de Cristiandad Movement

The Cursillos in Christianity Movement has a single purpose: that the Spirit of the Lord in Christ meets with the freedom of the human person and that this person, on discovering that they are loved by God, changes their horizon and perspective because they realize that God has them in mind.

—Eduardo Bonnín Aguiló, My Spiritual Testament

Eduardo’s greatest gift was making people happy.

—María Sureda, Mallorca, June 2011

Sitting around the table in the office of Fundación Eduardo Bonnín Aguiló (FEBA) in Palma de Mallorca, a group of longtime colleagues and friends of Eduardo Bonnín talked at length about his profound faith, humility, and sense of humor. During the course of our conversations that afternoon in June, these Mallorquín Catholics wept as they shared their profound gratitude, and laughed when they recalled funny moments spent with a man they credit with changing their lives. They remember him as an intellectual, a man who “always had a book with him,” and as someone who “never turned anyone away.”

Some of his colleagues and friends say he was “like a priest because he was always praying with people who came to him for help.” They say that “Eduardo,” as they refer to him, a life-long bachelor and ascetically minded, had a deep and abiding passion for helping laity develop their spiritual lives. The slightly built, bespectacled Mallorquín, a cradle Catholic, was always “on the move,” a man who “walked everywhere, and who would think deep thoughts as he walked.” An intellectual and profoundly spiritual man, Bonnín initiated the three-day Cursillo weekend “Cursillos for Pilgrim Leaders” today known as the Cursillos de Cristiandad or simply “Cursillos,” to bring a revitalized Catholic spirituality to the streets and the Church.

According to Bonnín’s longtime friend and collaborator, Guillermo Estarellas de Nadal, “It is important to understand that Eduardo wanted the culture of the time to change. He wanted people to want to change the culture and he wanted people to be great friends.” The culture he wanted to change was one marked by authoritarianism, fascist rhetoric and violence, and a deep sense of mistrust among Mallorquines. Bonnín, all of his close associates told me, encouraged amistad and wanted people to get along and accept their differences. He wanted to erase the sense of cultural anomie that so many Mallorquines experienced as a result of the Spanish Civil War by initiating a movement that emphasized new selves, new faith, and new communities.1

All of the Mallorquín cursillistas I spoke with emphasized Bonnín’s sense of humor and zest for life. They spoke at length about his profound Catholic faith, which included his attending daily mass and praying the rosary regularly, but they say Bonnín never took himself too seriously. He was a practical joker, a man who loved making people laugh. “Always keeping busy,” he made paper origami birds out of scraps of paper during Cursillo group reunion meetings, the first from a paper sugar container at a Palma café. For his ninetieth birthday celebration, cursillistas from around the world sent in their origami bird contributions, which were assembled by FEBA archivist Cristina González Duqué (the organization’s only paid staff member) and volunteers and framed for Bonnín.

Moreover, his colleagues say, Bonnín was exceedingly humble and unassuming. In keeping with the man, FEBA, the nonprofit organization dedicated to maintaining his memory, is a modest storefront building situated in Palma’s Calle de la Ferreria, in plain sight but easily missed, much as Bonnín has been overlooked as the initiator of what is today a global movement of Christian spirituality.

Bonnín, says his close friend Miguel Sureda, shunned the title “founder” of the movement. “He would say, ‘El Fundador is the name of a brandy and I am not a brandy!’” While he was uncomfortable with the honorific designation, Eduardo Bonnín Aguiló (1917–2008) is indeed the founder of the Catholic Cursillo movement. Bonnín’s Cursillo at its origins was a weekend experience for young Mallorquín men. The three days offered them the time and space to share their emotions, to talk about their personal lives and ambitions.2 While they were indeed a part of the sociocultural milieu in which they arose, these “Cursillos for Pilgrim Leaders” represent as much of an embrace of 1930s and 1940s Mallorquín island culture and its Catholicism as they do a rejection of repressive mainstream Spanish Catholic society. The society in which Bonnín’s weekend arose was one marked by nationalism, fascism, Catholic authoritarianism, and intolerance toward dissenters. Bonnín was a complex man whose formation of the Cursillos blended his love of tradition and deference to the institutional Church with a profound challenge to these same structures and ideologies. It is to an examination of his life, Mallorquín sociocultural realities, and the origins of the now-global movement in Christian spirituality that we now turn.

The Education of Eduardo Bonnín

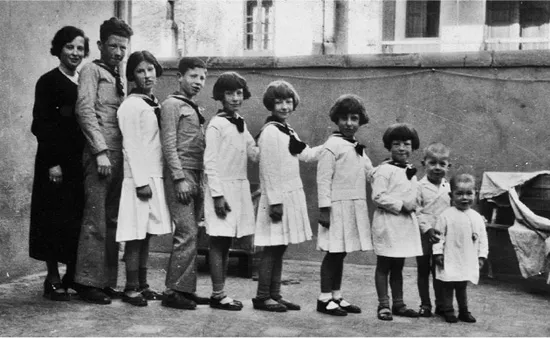

Eduardo Bonnín Aguiló was born May 4, 1917, in Palma de Mallorca, the island’s capital, the second of ten children to Don Fernando Bonnín Piña and Doña Mercedes Aguiló Forteza. Amalia, the eldest child, was the only one who went on to marry and have children. Sister Luisa was the third born, followed by brother Jordi, who worked for the family’s cereal and nut export business, where, according to FEBA archivist Cristina González Duqué, “he worked many hours and often with Eduardo.”3 Josefa, the fifth born, was followed by Fernando, who in his young adult years “spent a lot of time in mission work in Peru and who for a long time was a taxi driver in Palma, combining that work with his pastoral work.”4 María, the seventh child, was a Carmelite nun. The three youngest Bonnín Aguiló children, all women, are the only surviving siblings and share a modest home in Palma. Mercedes, like María, became a Carmelite nun, later leaving her order to become a social worker. The two youngest siblings, sisters Elvira and Pilar, also became social workers.

Eduardo was close to his parents and siblings and “always made a point in his life to be home for important feast days and celebrations.”5 He was brought up in a world of middle-class material privilege, devout Catholicism, and the opportunities that went along with his social status. Palma was urban and fast-paced, quite unlike the rural interior filled with groves of olive, fig, almond, and citrus trees. Eduardo grew up on an island that was and is breathtakingly beautiful. Palma is surrounded by the Mediterranean, and everywhere he looked, Eduardo had views of the sea and the bustling port. The west coast is rugged and hilly, long-known among hikers and pilgrims to the northern Santuari de Lluc for its challenging terrain, notably the famous Serra de Tramuntana, the mountain range that runs southwest to northeast.6 The views out west are stunning, the beaches and calas (coves) are rocky, and the waters ultramarine blue. The central part of the island is flatter, replete with fragrant orchards, while the east coast has mixed geographies of sandy beaches and coves, deserts, fishing villages, and even today a slower pace of living.

Eduardo Bonnín (far right) with his mother and siblings, ca. 1918. Courtesy of the Fundación Eduardo Bonnín Aguiló.

According to González Duqué, the Bonnín Aguilós were neither poor nor rich but “normal,” yet in the 1940s they were most certainly among the island’s elite. The family was not ostentatious with its wealth. They blended in with Palma society and were known for their Catholic piety and outreach to the community. Catalina (“Cati”) Granados, a longtime friend of the Bonnín Aguilós, says that she stopped by the family’s store several times each week to buy milk and to chat with Doña Mercedes, who “was like a mother to all of us. I looked forward to going to the store and always enjoyed our conversations.”7

Thanks to the success of the family’s export company, Don Fernando and Doña Mercedes had the means to educate all of their ten children with private Catholic tutors, Augustinians. Like his siblings, Eduardo was exceedingly well-read and received a Catholic liberal arts education. His family’s library was well-stocked with books, a luxury and indicator of their social status. He and his siblings were encouraged to read widely and broadly, and this familial, social, and educational milieu predisposed them toward a well-rounded, liberal arts way of viewing the world. Eduardo came to believe that “at the center everybody is the same” and that intellectually and spiritually enlightened people could bring about reform in their communities—their workplaces, their Church, and their homes.8

The Bonnín Aguilós were immersed in a nationalist, authoritarian society, and my ethnographic research reveals a conservative Catholic family that nurtured devotional piety in its children as much as it encouraged them to read widely and to expose themselves to a broad range of ideas. As the son of upper-middle-class merchants, Eduardo soon learned that reading was his escape, that he could travel and experience the world through books. Yet his immediate reality was that he was raised in the closed cultural and religious world of Mallorquín Catholicism, a Church and faith that emphasized tradition, embodied piety, and sacrifice. The Bonnín Aguilós’ Palma home was near the Plaça Santa Eulalia and its famous Cathedral of Santa Maria, “la Seu,” the towering, gothic structure that overlooked the Mediterranean and dominated the city. As it does today, la Seu was a symbol of Catholic triumphalism over Islam and the “Moors,” whose mosque was displaced by the cathedral when the latter was begun in 1229 and eventually completed in 1601.9

The cathedral, 121 meters long and 55 meters wide, with a nave 44 meters tall, is the most imposing of the many Catholic architectural sites that dot the island landscape. Mallorca is famous for its twelfth-century Lluc monastery, dedicated to the Virgin Mary and located in the island’s northwest. Mallorquines then and today climb the rugged terrain of the Tramuntana to pay their respect to la Virgen.

Eduardo Bonnín loved the universal Church and had a deep devotion to the Virgin Mary. He began attending daily mass as a young child, drawn to a disciplined life that included prayer, fasting, and pilgrimage. The first Cursillo weekend he offered at age twenty-seven incorporated Catholic spirituality, Marian devotionalism, readings in psychology, and Catholic social teachings he encountered and nurtured in his young adult life. When he was seventeen, he attended La Salle College in Palma, located in the city center at 4b Avenida Sant Joan de la Salle, in the shadow of the massive Seu. He was influenced by the faculty’s emphasis on training Christian teachers who would help spread peace and justice. At La Salle, he continued to read voraciously and fed his liberally minded spiritual and intellectual disposition. After a year at La Salle, at age eighteen, Eduardo Bonnín joined other able bodied Spanish young men at the time and entered military service.

Eduardo Bonnín as a soldier. Courtesy of the Fundación Eduardo Bonnín Aguiló.

For the first time in his life, he confronted young men who were neither devout Catholics nor well educated. His nine-year military service was a pivotal juncture in his life, and his outlook was indelibly changed forever. He served for as long as he did out of a sense of duty and because he was drawn in by privates’ oral histories. While in the barracks, he began to test the many theories he had gained through reading and contemplation, and he began earnestly working on making religion meaningful and relevant to the men around him. The “conflict” between his nurturing family environment and the “completely different” environment of the barracks led to his ethnographic, spiritual, and psychological efforts to make religion meaningful and freeing for men. He came to believe that the war and the Church’s authoritarian stance led most youth to have “a wrong and fearful concept of religion” and that, for them, “religion was just a series of prohibitions placed upon them which hindered their lives and prevented them from using the freedom they could enjoy according to their own whim.”10

During these nine years Bonnín spent all of his extra time in the barracks as an ethnographer, “trying to find out what people were like” and came to the conclusion that “at the very centre, everybody is the same.”11 He writes in My Spiritual Testament that “the underlying original seed of Cursillo grew out of the conflict that took place in me, when the education I had received from the family environment that I had always lived in collided with the environment at the barracks.”12 After his compatriots visited prostitutes in Palma’s red-light district, he talked with them, asking if they “enjoyed themselves.” Although they always replied “yes,” the deeper they went in their conversation, each soldier would share his guilt, shame, and remorse.13

This life-changing experience of military service led to his epiphany that the environment is instrumental in shaping a man and his culture, and he decided that he wanted to help change the environments in which these men found themselves. His experience in Palma’s barracks, combined with his readings and reflections, led him to introduce an alternative way of thinking about and experiencing religion. At the age of twenty-three, he read Pope Pius XII’s 1940 papal letter on Catholic Action (the worldwide Catholic revitalization movement), a document that “had an unusual effect on me” and led him to examine “each of the constellations of individuals in the world, in my world and in the Church that I knew and frequented.” He was excited by the pope’s commitment to “good pastors” who would lead “lost sheep” into the “safety, life and joy in the return to the fold of Christ.”14

While never referring to himself as a leader, Bonnín came to see himself as someone who could help bring lost sheep (in this case, soldiers) back to Christ, and he dedicated himself to this challenge. In 1943, he was swept into the Spanish Catholic Action (CA) Cursillos by his godfather, José Ferragut, the architect and president of Catholic Action for Youths in Mallorca. Bonnín was twenty-six at the time and attended the Cursillos for pilgrims at the Lluc monastery. He wa...