![]()

1

TWO GENERALS AND THEIR ARMIES

Two generals — corps commanders — confronted one another at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, late on the afternoon of 1 July 1863. One, a Confederate lieutenant general, whose troops had just smashed the Union Eleventh Corps and driven it in retreat through the streets of Gettysburg, sought to determine if he should push on and try to seize the high ground just south of the town where Union troops were rallying. The other, a Union major general, was on that high ground, Cemetery Hill, and was attempting to organize his badly mauled forces to meet an attack that he believed would soon come.

The generals were extraordinary fellows. Both were graduates of West Point but from classes fourteen years apart. Both were brave beyond doubt, and both had already lost limbs in battle—one a leg, the other an arm. Both were eccentric, and both had been affected by the recent battle of Chancellorsville but in very different ways. The Union general and his corps had been crushed and had suffered heavy casualties there, but worse, many people in and out of the Army of the Potomac blamed them for the Union defeat and vilified them. The Confederate general had not been at Chancellorsville himself, but his men had triumphed there, and now he commanded them in place of the mortally wounded Thomas J. (Stonewall) Jackson.

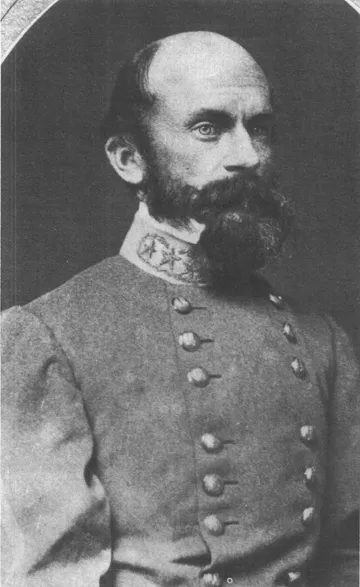

The Confederate lieutenant general was Richard Stoddert Ewell. Ewell was a Virginian and the grandson of Benjamin Stoddert, the nation’s first secretary of the navy. Although Ewell had prominent family connections, he had been reared in near poverty at “Stony Lonesome,” a farm near Manassas, Virginia.1 Ewell managed to get an appointment to West Point’s class of 1840, which included William T. Sherman and George H. Thomas. After graduating, he served on the frontier with the 1st Regiment of Dragoons. During the Mexican War Ewell and his company formed Gen. Winfield Scott’s mounted escort, and he won a brevet. After the war, Ewell campaigned long and actively in the Southwest against the Apaches. He had performed well throughout his career and had developed an enviable reputation among his peers. Then came the Civil War.

Ewell did not support secession and had much to lose by it. Nevertheless, he resigned his Old Army commission on 7 May 1861 and entered Virginia’s service as a lieutenant colonel. He briefly commanded a cavalry camp of instruction at Ashland, Virginia, and on 17 June became a brigadier general. He commanded a brigade at First Manassas but saw no heavy fighting. In February 1862, now a major general, he received command of a division and led it in the Shenandoah Valley during Jackson’s campaign there. He commanded his division in the Seven Days' battles, at Cedar Mountain, and at Groveton, where he was shot in the left knee. This wound led to the amputation of his left leg, and Ewell missed the battles of Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville.

Ewell proved to be a skillful and successful division commander, and unlike Ambrose P. Hill and others, he was able to get along with Stonewall Jackson. His bravery was legendary, and often he commanded his division as he had led his dragoon company—from the front.

Ewell was no Adonis. He was five feet, eight inches tall, thin, and had gray eyes and a fringe of brown hair on a domed bald head. Richard Taylor, who had commanded the Louisiana brigade in his division in the Shenandoah Valley, described Ewell as having “bright prominent eyes, a bomb-shaped, bald head, and a nose like that of Francis of Valois [that] gave him striking resemblance to a woodcock.” In addition, he had a lisp that gave an added dimension to his pungent comments and to the blistering profanity he used when irritated.2

Ewell had chronic health problems associated with malaria and with his digestive system, but these ailments did not adversely affect his military performance. He rivaled Stonewall Jackson in eccentricity, but when not irritated he was pleasant and affable. He seemed devoid of vanity and had little untoward ambition. In the postwar years, when all too many former Confederate leaders sought to buttress their reputations by imputing blame for Confederate misfortunes to others, Ewell, like Gen. Robert E. Lee, remained silent. After his death in 1872, his stepdaughter Harriet Stoddert Turner wrote, “I know how much he suffered from ignorant censure & unjust criticism.”3

Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell (MM)

Ewell had been a romantic in his youth and was an ardent admirer of young ladies of quality, few of whom he met on the frontier. He had wooed his cousin Lizinka Campbell without success but had not seriously pursued other ladies he admired. Then, during the recuperation from the amputation of his left leg, he got the chance to woo Lizinka again. By then she was the wealthy widow of a Mississippi planter named Brown, and Ewell won the widow’s heart and hand. The new Mrs. Ewell, who curbed the general’s swearing, was the mother of Maj. G. Campbell Brown, who had been on Ewell’s staff since early in the war and in some measure would become his Boswell.

Ewell, at forty-six years of age and minus his left leg, returned to active duty after Chancellorsville to take command of Jackson’s old corps, the Second Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia, with the grade of lieutenant general. His assignment met with wide approval. Jedediah Hotchkiss, the corps' topographical engineer, recalled that “no risk is run in asserting that the entire Second Corps desired him to be Jackson’s successor, and his appointment gave general satisfaction to the officers and men of that grand body of fighters and victory winners.”4

When Ewell accepted the corps command, he tactfully invited Jackson’s staff to stay on with him. After meeting his new commander again, Maj. Alexander S. (Sandie) Pendleton, the corps adjutant, wrote: “General Ewell is in fine health and in fine spirits,—rides on horseback as well as anyone needs to. The more I see of him the more I am pleased to be with him. In some traits of character he is very much like General Jackson, especially in his total disregard of his own comfort and safety, and his inflexibility of purpose. He is so thoroughly honest, too, and has only one desire, to conquer the Yankees. I look for great things from him, and am glad to say that our troops have for him a good deal of the same feeling they had towards General Jackson.”5

The loss of Jackson triggered a reorganization of the Army of Northern Virginia. For some time, it had had two corps commanded by Gens. James Longstreet and Stonewall Jackson plus a cavalry division commanded by Maj. Gen. James E. B. (Jeb) Stuart. After Chancellorsville, General Lee had to find replacements for ranking officers lost in the battle or found wanting and sought to obtain greater efficiency by reducing the size of his corps. His solution for the latter was to reorganize his 75,000 troops into three corps of three divisions each and a cavalry division together with supporting artillery. With three exceptions, each infantry division would have four brigades. The artillery, formed into battalions, would be assigned to the three corps and to the cavalry.

In this new organization, General Longstreet would continue to command the First Corps, Ewell would take the Second, and the Third would go to A. P. Hill, formerly commander of the famous Light Division. It is significant perhaps that General Lee had not recently worked closely with Hill and that Ewell had worked directly under Jackson and not Lee. In short, Lee would soon launch a major campaign with two new corps commanders, one of whom had not previously been his immediate subordinate. This would affect Ewell in particular, for he was accustomed to the tight-rein style of command employed by Stonewall Jackson and not the hands-off manner of General Lee.

Ewell’s corps had divisions commanded by three major generals: Jubal A. Early, Edward Johnson, and Robert E. Rodes. Early’s division had four brigades: a Louisiana brigade commanded by Harry T. Hays, a Georgia brigade commanded by John B. Gordon, Virginians under William (“Extra Billy”) Smith, and Robert F. Hoke’s North Carolinians. Hoke, however, had been wounded at Chancellorsville, and in his absence Col. Isaac E. Avery of the 6th North Carolina Regiment would lead his Tarheels.

Rodes’s division underwent some change. It had been Daniel H. Hill’s division, but Rodes had commanded it at Chancellorsville and had done well. Now it was his. For some reason, the division had five brigades instead of the usual four. Rodes’s old Alabama brigade was commanded by Col. Edward A. O’Neal of its 26th Alabama Regiment. Brig. Gen. George Doles continued to command his Georgia brigade, and there were two North Carolina brigades under Brig. Gens. Stephen D. Ramseur and Alfred Iverson. It also had a large new North Carolina brigade under Brig. Gen. Junius Daniel.

The greatest changes had taken place in the division once commanded by Stonewall himself. It was said that Jackson had been saving the command of this division for Isaac R. Trimble, who had been wounded at Second Manassas, but Trimble had not yet recovered. Therefore, General Lee assigned it to Maj. Gen. Edward Johnson, a newcomer to the Army of Northern Virginia.6

But that was not all. Each of the division’s four brigades needed a new commander. Elisha F. Paxton of the Stonewall Brigade had been killed at Chancellorsville; his place would be taken by James A. Walker, who had commanded other brigades at Antietam and Fredericksburg. John R. Jones was dismissed from service after having left the field at Chancellorsville; his place would be taken by John M. Jones. There was a special problem involving North Carolina-Virginia pride in the brigade once led by Raleigh E. Colston; General Lee resolved it by assigning the 1st Maryland Battalion to the brigade and placing Brig. Gen. George H. Steuart, a Marylander, in command. The final brigade, that of Brig. Gen. Francis R. Nicholls, needed at least a temporary commander for Nicholls had lost a foot at Chancellorsville. General Lee designated Col. Jesse M. Williams of the 2d Louisiana Regiment as the brigade’s acting commander.7

Therefore, though the Army of Northern Virginia had a new and seemingly more efficient organization, two of its corps had commanders new to their assignments. Furthermore, one, Richard S. Ewell, had lost a leg and was returning to duty with whatever handicap that condition might create. The other new commander, Lt. Gen. A. P. Hill, had worsening health. We know with the benefit of hindsight that Hill would not measure up to the reputation he had gained as a division commander. Both of these generals would bear some responsibility for Confederate operations against Cemetery Hill at Gettysburg.8

The Army of the Potomac had suffered 17,000 casualties at Chancellorsville and had lost a number of units whose period of service had expired. Yet it was not reorganized. In June 1863 it continued to consist of seven corps of infantry, each supported by a “brigade” of artillery, most having five batteries, a cavalry corps supported by two brigades of artillery, and its Artillery Reserve—a powerful collection of twenty-one batteries formed in five brigades. It had three new corps commanders: Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock of the Second Corps, George Sykes of the Fifth, and Brig. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton of the Cavalry Corps.9

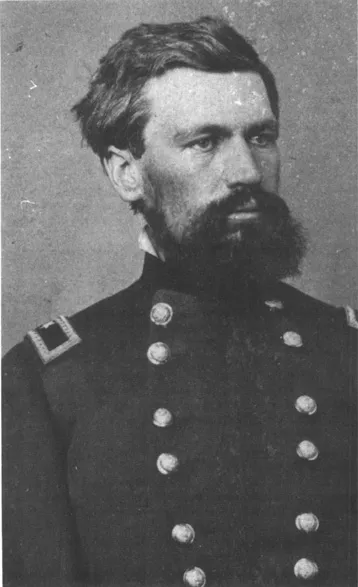

Six of the seven infantry corps were proven fighting machines, but popular opinion within the army considered one corps, the Eleventh, to be a question mark at best. Formerly the First Corps of John Pope’s Army of Virginia, the Eleventh Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel, had come to the Army of the Potomac after the battle of Second Manassas. Through design or fortune, it had not taken part in the heavier fighting either at Antietam or Fredericksburg, and Sigel had left it in February 1863. Gens. Carl Schurz and Adolph von Steinwehr, two of its division commanders, were its acting commanders for a few weeks, and then Maj. Gen. Oliver Otis Howard took command.

Howard’s appointment was made neither in heaven nor by angels. In retrospect, the post would seem to have called for an experienced, nononsense disciplinarian like Hancock or Maj. Gen. John F. Reynolds. Instead it fell to an officer whose demonstrated ability was balanced by his being young and rather inexperienced.

Howard was born in Leeds, Maine, on 8 November 1830, the son of a farmer who died when he was nine. He attended public schools and in 1850 graduated from Bowdoin College. Although he had taught school, he was undecided about a career, and when an uncle who was a congressman offered him an appointment to West Point, he took it. Therefore, at age nineteen, with a college degree already in hand, he entered the academy’s class of 1854.10 Howard had no problem with his studies at West Point, but he was placed in Coventry for a time during his plebe year for reasons unknown today. His classmates included W. Dorsey Pender, Stephen H. Weed, and Thomas H. Ruger, and by the time of his graduation he numbered G. W. Custis Lee and Jeb Stuart among his closer friends.11

After graduation, Howard married and served as a subaltern in the Ordnance Department. In 1857 he returned to West Point as an instructor in mathematics. In the years that followed, he fathered three children, conducted a Bible class for enlisted men and civilians, and studied theology with a local Episcopal priest with the idea of going into the ministry. Religion permeated his life, in much the same way that it had influenced Stonewall Jackson’s.12

War came, and in June 1861 Howard exchanged his lieutenancy for the colonelcy of the 3d Maine Regiment. This appointment suggests that though he might not have dabbled in politics, he had support from Maine’s important politicians. Howard was twenty-nine at this time. A member of the 3d Maine described him then as a “pale young man, . . . slender with earnest eyes, a profusion of flowing moustache and beard.” Actually, he was about five feet, nine inches tall and had blue eyes. A later description by Maj. Thomas W. Osborn, his chief of artillery, held him to be of slight build with heavy dark hair and “undistinguished” eyes, a strong but not an impressive man. Frank A. Haskell of the Second Corps wrote that Howard was a “very pleasant, affable, well dressed little gentleman”—something that no one would have said of Ewell.13

Major Osborn had other things to say of Howard as he saw him in 1865. He wrote that the general “never overcame mannerisms such as fidgety gestures and a shrill voice.” On the other hand Osborn termed Howard “the highest toned gentleman” he had ever known. He believed him to be neither a profound thinker like Sherman nor a man with “large natural ability.” He did not “call out from his troops the enthusiastic applause that Generals Logan and Hooker do,” yet, wrote Osborn, “every officer and man has unbounded confidence in him.” This might have been the real Howard of 1865, but it was not necessarily the Howard of 1861.14

Howard took the 3d Maine to Washington, D.C., to train it. However, he received an assignment to a brigade command and led his brigade to Manassas only about two months after he resigned his lieutenancy. Howard found the battle particularly offensive because it took place on a Sunday. He became unnerved momentarily by the sights and sounds of the fight, but he responded to his fright by praying to God that he might do his duty, and he claimed that the fear left him, never to return.15

Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard (WLM)

Howard became a brigadier general on 3 September 1861. He led a Second Corps brigade in the Peninsular campaign until he fell at Fair Oaks on 1 June 1862 with two wounds, one of which cost him his right arm. He returned to Maine to recuperate but did not dally and was back with the army and in command of another Second Corps brigade in time for Second Manassas. He led this brigade at Antietam, and when his division commander, John Sedgwick, was wounded, Ho...