![]()

Chapter One

Mobilizing for War

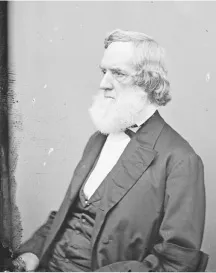

In January 1861 the commandant of the Philadelphia Navy Yard, Captain Samuel Francis Du Pont, wrote an anguished letter to his longtime friend Commander Andrew Hull Foote, head of the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Fifty-seven and fifty-four years old, respectively, Du Pont and Foote had served in the U.S. Navy since they were teenagers. They were destined to become two of the first five admirals in American history a year and a half later. Descendant of a French royalist who had emigrated to America during the French Revolution, Du Pont was a tall and imposing figure with ramrod-straight posture and luxuriant mutton-chop whiskers. Although he resided in the slave state of Delaware, Du Pont had no time for secessionists who were at that moment taking seven states out of the Union and talking about uniting all fifteen slave states in a new nation. “What has made me most sick at heart,” he wrote, “is to see the resignations from the Navy” of officers from Southern states. “If I feel sore at these resignations, what should a decent man feel at the doings in the Pensacola Navy Yard?” On January 12 Captain James Armstrong, commandant of the Pensacola Navy Yard, had surrendered this facility and Fort Barrancas to militia from Florida and Alabama without firing a shot. A native of Kentucky and one of the most senior captains in the navy with fifty-one years of service, Armstrong feared that an attempt to defend the navy yard might start a civil war. For this decision he was subsequently tried by court-martial and suspended for five years, ending his career in disgrace. His act brought contempt and shame to the navy, wrote Du Pont. “I stick by the flag and the national government,” he declared, “whether my state do or not.”1

There was no question where Foote’s allegiance lay. A Connecticut Yankee, devout Christian, and temperance and antislavery advocate, he fervently believed that patriotism was next only to godliness. Concerning another high-ranking naval officer, however, there were initially some doubts. Captain David Glasgow Farragut had served fifty of his fifty-nine years in the U.S. Navy when the state he called home, Virginia, contemplated secession in 1861. Farragut had been born in Tennessee and was married to a Virginian. After his first wife died, he married another Virginia woman. He had a brother in New Orleans and a sister in Mississippi. “God forbid I should ever have to raise my hand against the South,” he said to friends in Virginia as the sectional conflict heated up.2

Captain Samuel Francis Du Pont. This photograph probably dates from the late 1850s. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Many of Farragut’s acquaintances expected him to cast his lot with the new Confederate nation. But he had served at sea under the American flag in the War of 1812 and the Mexican-American War, and he was not about to abandon that flag in 1861. When the new president, Abraham Lincoln, called up the militia after the Confederates attacked Fort Sumter, Farragut expressed approval of his action. His Virginia friends told him that anyone holding this opinion could not live in Norfolk. “Well, then,” Farragut replied, “I can live somewhere else.” He decided to move to New York. “This act of mine may cause years of separation from your family,” he told his wife, “so you must decide quickly whether you will go north or remain here.” She resolved to go with him. As they prepared to leave, the thin-lipped captain offered a few parting words to his Virginia neighbors: “You fellows will catch the devil before you get through with this business.” When Virginia seceded and its militia seized the Norfolk Navy Yard, Farragut told his brother: “I found things were growing worse . . . and told her [his wife] she must go at once. We all packed up in 2 hours & left on the evening steamer.”3 Farragut no doubt remembered this hurried departure when his victorious fleet steamed into New Orleans almost exactly a year later.

One of Farragut’s Southern friends made the same choice he had made. Born in South Carolina, Percival Drayton was one of the most promising officers in the navy when his native state seceded on December 20, 1860. Although several of his numerous relatives fought for the Confederacy—including his older brother Thomas, a low-country planter and Confederate general—Percival never hesitated. “The whole conduct of the South has destroyed the little sympathy I once had for them,” he wrote a month after South Carolinians fired on Fort Sumter. “A country can recover from anything except dismemberment. I hope this war will be carried on until any party advocating so suicidal a course is crushed out.” Drayton became one of the best fighting captains in the Union navy, serving with Du Pont in the capture of Port Royal and the attack on Charleston and with Farragut as fleet captain at Mobile Bay. While commanding the steam sloop USS Pawnee in operations along the South Carolina coast in November 1861, Drayton wrote to a friend in New York: “To think of my pitching in here right into such a nest of my relations . . . is very hard but I cannot exactly see the difference between their fighting against me and I against them except that their cause is as unholy a one as the world has ever seen and mine is just the reverse.”4

Drayton’s and Farragut’s loyalty to the Union was not typical of officers from Confederate states. Some 259 of them resigned or were dismissed from the navy. Most went into the new Confederate navy. One hundred and forty of them had held the top three ranks in the U.S. Navy: thirteen captains, thirty-three commanders, and ninety-four lieutenants. Forty Southern officers of these ranks, mostly from border states that did not secede, remained in the Union navy.5

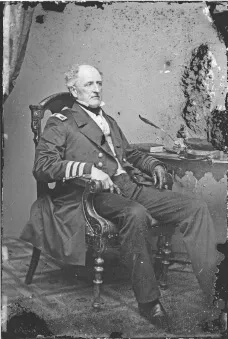

One of those who went South became the first—and, until almost the end of the war, the only—admiral in the Confederate navy: Franklin Buchanan of Maryland. He was a veteran of forty-five years in the U.S. Navy, the first superintendent of the Naval Academy when it was established in 1845, second in command of Matthew Perry’s famous expedition to Japan (1852–54), and commandant of the Washington Navy Yard when the Civil War began. Three days after a secessionist mob in Baltimore attacked the 6th Massachusetts Militia on its way through the city to Washington on April 19, Buchanan entered the office of Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles. The two men were a study in contrasts. Buchanan was smooth-shaven with a high forehead and receding hairline, thin lips turned down in a perpetual frown, and an imperious manner of command. Welles’s naval experience was limited to a two-year stint as the civilian head of the Bureau of Provisions and Clothing during the Mexican-American War. A long career as a political journalist in Connecticut had given little promise of the resourceful administrative capacity he would demonstrate as wartime secretary of the navy. The wig he wore with brown curly hair down almost to his shoulders contrasted oddly with his long white beard, which caused President Lincoln to refer to him fondly as “Father Neptune.” The president had announced a blockade of Confederate ports five days earlier, and Welles needed all the help he could get from experienced officers like Buchanan to make it work. But Buchanan had come to tender his resignation from the navy. The riot in Baltimore convinced him that Maryland would secede and join the Confederacy. It was his duty to go with his state. Welles expressed his regrets, but he did not try to talk Buchanan out of resigning. “Every man has to judge for himself,” acknowledged the secretary.

Union Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

As the days went by and Maryland did not secede, Buchanan had second thoughts. Perhaps he had acted rashly. He tried to withdraw his resignation. But Welles wanted no sunshine patriots in his navy. Like Du Pont, he was angry at officers who had resigned to fight against their country. To Buchanan’s request to retract his resignation, the secretary replied icily: “By direction of the president, your name has been stricken from the rolls of the Navy.”6

Welles had been soured by an experience three weeks earlier concerning another senior Southern officer, Captain Samuel Barron of Virginia. As Welles sat eating dinner at the Willard Hotel on the evening of April 1 (his wife and family had not yet joined him in Washington), he was startled to receive a packet of papers from John Nicolay, one of Lincoln’s private secretaries. Welles was even more astonished when he read a series of orders signed by the president that reassigned Captain Silas Stringham from his post as Welles’s assistant to select officers for various commands and replaced him with Captain Barron. Welles rose quickly from his unfinished dinner and rushed to the White House. As Father Neptune burst into Lincoln’s office brandishing the orders like a trident, Lincoln looked up apprehensively. “What have I done wrong?” he asked. Welles showed him the orders, which Lincoln sheepishly admitted he had signed without reading carefully. They had been prepared under Secretary of State William H. Seward’s supervision, he said, and the president was so distracted by a dozen other problems that he had mistakenly trusted Seward’s recommendation.

Commodore Franklin Buchanan of the Confederate navy. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

This was not the first nor the last time Seward meddled with matters outside his department. Lincoln told Welles to ignore the orders. Both men recognized that this incident was part of Seward’s effort to keep the Upper South states, especially Virginia, from seceding. Still under the erroneous impression that he was the “premier” of the administration, Seward naively believed that by giving Barron authority over personnel matters in the Navy Department, he would cement Barron’s—and Virginia’s—loyalty to the Union. Welles considered Barron a secessionist—the last man to be trusted with personnel assignments. He was right. Unknown to Lincoln or Welles at the time, Barron had already been appointed a captain in the Confederate navy—which as yet scarcely existed—and would soon resign to go South.7

Seward’s fingerprints were all over another scheme to interfere with the navy as part of his increasingly desperate intrigues to conciliate the South by avoiding confrontation with the Confederacy at Fort Sumter. The situation at that potential tinderbox in Charleston Harbor had remained tense since South Carolina artillery in January had turned back the chartered ship Star of the West, which was carrying reinforcements to the fort. An uneasy truce likewise existed between the Florida militia that seized Pensacola and U.S. soldiers who continued to hold Fort Pickens across the entrance to Pensacola Bay. The first effort by the new Lincoln administration to reinforce Fort Pickens had foundered because the orders to the captain of the USS Brooklyn to land the troops were signed by the army’s adjutant general and not by anyone in the Navy Department. Welles immediately signed and sent new orders, which were successfully carried out on April 14.8

In the meantime, however, Lincoln had also decided to resupply the U.S. garrison at Fort Sumter, even at the risk of provoking the Confederates to fire on the fort and supply ships. Seward opposed this decision. He continued to insist that a confrontation at Fort Sumter would start a war and drive the Upper South into secession. He also maintained that withdrawal of troops from the fort would encourage Unionists in the South (whose numbers he vastly overestimated) to regain influence there. Lincoln feared that withdrawal from Fort Sumter, which had become the master symbol of divided sovereignty, would undermine Southern Unionism by implicitly recognizing Confederate legitimacy.

Lincoln’s Postmaster General, Montgomery Blair, thought so too. He introduced Lincoln to his brother-in-law Gustavus V. Fox, a former navy lieutenant, who suggested a way to run supplies and troops into Fort Sumter at night with shallow-draft tugboats. With his rotund figure and high, balding forehead, Fox did not look much like a dashing naval officer. But he had a can-do manner that convinced Lincoln—who was already weary of advisers who told him that something or other could not be done—that this thing could be done. He told Fox to work with Welles to assemble the supplies and warships to escort the troop transports and tugs to Charleston.9

Only three warships and the Treasury Department’s revenue cutter Harriet Lane were available for the mission. The largest warship was the USS Powhatan, a 2,400-ton sidewheel steamer carrying ten big guns. It became the centerpiece of a monumental mix-up that illustrated the disarray of the Lincoln administration in the midst of this crisis. On April 1 Welles ordered the Brooklyn Navy Yard to ready the Powhatan for the Fort Sumter expedition. On the same date, Seward wrote his infamous memorandum to the president suggesting that he might reunite the nation by provoking a war with France or Spain and urging him to reinforce Fort Pickens as an assertion of authority but abandon Fort Sumter as a gesture of conciliation. Lincoln in effect gently slapped Seward’s wrist for this effrontery. But on that day Seward also engineered the order placing Samuel Barron in charge of assigning naval personnel, which Welles got Lincoln to rescind. And Seward promulgated yet another dispatch on April 1 and got Lincoln to sign it; this one ordered the commander of the Brooklyn Navy Yard to prepare the Powhatan for an expedition to reinforce Fort Pickens. “She is bound on secret service,” directed Seward, “and you will under no circumstances communicate to the Navy Department the fact that she is fitting out.”10

Captain Foote, head of the navy yard, must have scratched his head when he received these two contradictory orders, the first signed by the secretary of the navy and the other by the president. Was one of them an April Fool’s joke? Foote and Welles had been friends since their schoolboy days together in Connecticut forty years earlier. Despite the admonition to keep the second order secret from Welles, Foote sent a cryptic telegram questioning it.11 On April 5 Welles finally realized what was going on. He confronted Seward, and both rushed to the White House. Although it was almost midnight, Lincoln was still awake. When he understood the nature of this messy contretemps, he ruefully admitted his responsibility and told Seward to send a wire to the navy yard to restore the Powhatan to the Fort Sumter expedition. Seward did so, but whether intentionally or not, he signed the telegram simply “Seward” without adding “By order of the President.” When it reached Brooklyn, the Powhatan had already left under command of Lieutenant David D. Porter. A fast tug caught up with Porter before he reached the open sea, but when he read the telegram signed by Seward, he refused to obey it, claiming that the earlier order signed by Linco...