eBook - ePub

The Citizen Patient

Reforming Health Care for the Sake of the Patient, Not the System

- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Citizen Patient

Reforming Health Care for the Sake of the Patient, Not the System

About this book

Conflicts of interest, misrepresentation of clinical trials, hospital price-fixing, and massive expenditures for procedures of dubious efficacy — these and other critical flaws leave little doubt that the current U.S. health-care system is in need of an overhaul. In this essential guide, preeminent physician Nortin Hadler urges American health-care consumers to take time to understand the existing system and to visualize what the outcome of successful reform might look like. Central to this vision is a shared understanding of the primacy of the relationship between doctor and patient. Hadler shows us that a new approach is necessary if we hope to improve the health of the populace. Rational health care, he argues, is far less expensive than the irrationality of the status quo.

Taking a critical view of how medical treatment, health-care finance, and attitudes about health, medicine, and disease play out in broad social and political settings, Hadler applies his wealth of experience and insight to these pressing issues, answering important questions for Citizen Patients and policy makers alike.

Taking a critical view of how medical treatment, health-care finance, and attitudes about health, medicine, and disease play out in broad social and political settings, Hadler applies his wealth of experience and insight to these pressing issues, answering important questions for Citizen Patients and policy makers alike.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Citizen Patient by Nortin M. Hadler, M.D.,Nortin M. Hadler M.D. in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Médecine & Prestation de soins de santé. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. Shills

When Profit Trumps Benefit

Health care in the United States is ethically compromised. About that, there is no debate. The debate is over the degree of compromise and the even-more-heated question of what to do about it. The Institute of Medicine and nearly every other professional organization in the health arena have chimed in. The areas examined include medical errors, ethnic and racial disparities in provision of care, uneven quality of care, antiquated record keeping, and administrative inefficiency. They talk about overdiagnosis, overtreatment, and overhead. Each of these areas is surrounded by clouds of obfuscation, a predictable result of all the finger pointing. Hiding in the clouds is an essence that renders the U.S. healthcare system essentially ethically bankrupt. That essence is conflict of interest.

A goodly percentage of the wealth of the country, approaching 20 percent of the gross domestic product each year, is commandeered by the health-care system. In chapter 2, we examine the health expenditures and healthfulness of many countries in the resource-advantaged world. Yet the United States gets the least “bang” despite expending the most “buck.” Most of the monies expended in the United States—at least half of this largesse—pass through the system into the pockets of “stakeholders” without advantaging a single patient. The per capita expenditure of every other resource-advantaged country is half that of the United States or less without disadvantaging their patients by even an iota. In the United States, the “system” and its myriad stakeholders are no longer the infrastructure; they are the raison d’être. Furthermore, the marketing, lobbying, and pandering is so well funded that entire institutions have been co-opted. Congress tilts toward the status quo thanks to the efforts of legions of lobbyists, as many as six per member of Congress. Medical education is now a “loss center” barely discernible in “academic health centers,” which are barely academic and consider health care no more than a profit center. Regulatory agencies are often handmaidens of a political agenda or of powerful outside influences. The list goes on and depressingly on.

There is a desperate need for a voice on Capitol Hill or in the White House demanding that the health-care system claim the moral high ground. A demonstrable benefit for patients must trump any demonstrable benefit for any other stakeholder. If an intervention has been studied and can’t be shown to offer a meaningful benefit, it does not matter how efficiently or expertly or profitably it is accomplished; it should not be done. Any voice calling for that kind of change will be quickly stifled by those with vested interests in the marginally useful and the useless, unless Citizen Patients take up the cause.

The Disclosure Dodge in the Clinic

Arrangements between individual practitioners and drug or device purveyors are a rich source of conflict of interest. Academic health centers and unaffiliated hospitals are racing to write or expand policy statements on conflicts of interest that relate to the clinical activities of individual practitioners. Several in Congress, Senator Chuck Grassley (R) of Iowa for one, are investigating and legislating. Policy is targeting marketing methods that seem on the surface to be innocuous: the on-site “detailing” by drug and device representatives, the trinkets and “free meals,” the samples that cause a physician to become more familiar with prescribing the product than with the product’s limitations, the sponsored educational programs that engender comfort with the sales personnel if not the product, and other tactics. All of these are easy targets for those putting forth policies that treat the collective conscience of my profession. That’s overdue. So, too, is a peer review that examines the feigned or real naïveté on the part of professionals who claim they are above being influenced in such an obvious way. But physicians owe their patients much more. The fact that policy rather than personal ethics is necessary to bring an end to these obvious marketing schemes is a reproach to my profession.

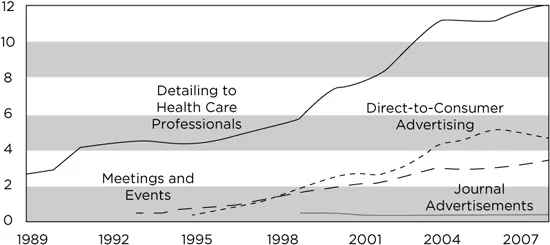

“Detailing” is the pharmaceutical industry’s euphemism for marketing to physicians at the site of their practice. Great numbers of young, educated men and women are recruited to this task because they are attractive and articulate and likely to be found so by practitioners. They are schooled in presenting the clinical pharmacology of their wares in the most favorable light. They are not to overstep the boundaries defined by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the use of any of their wares, but they typically learn how to tiptoe along the limits. If they are caught crossing that line, their company faces fines and bad press, which some pharmaceutical firms have managed to overcome in a number of notorious examples, such as in the marketing of particular “pain pills.” The detailing representatives (“reps”) show up in offices and clinics and ask for signed permission to stock a medicine cabinet with samples. They make appointments with the practitioners to ply them with the “details” that should convince the practitioner of the value of their product. By default, detailing may be the practitioner’s only exposure to the relevant clinical science since independently seeking such information is time-consuming and, for many, less appealing than a discussion with an attractive sales representative at the office or over lunch. Because of the inherent bias in such information, direct marketing to practitioners has been banished from many institutions, though not all. Those that have not denied access are likely to be swamped with free lunches and smiling sales representatives, with their bags full of samples, trinkets, and other gifts; and even though these representatives are banned from many institutions, private practices often remain open to them. Detailing to healthcare professionals remains a leading expenditure in the pharmaceutical industry’s marketing budget (Figure 1).

There is much more that affronts moral philosophy, much that is not as concrete as a drug sample or a pen with a logo. I am saddened to have to write this chapter. But this is an era in medicine when ethical failing is not idiosyncratic. We are not talking about the occasional rotten apple; we are talking about blight on the crop. Shouldn’t we expect, at a minimum, that our physician disclose all real and potential conflicts of interest that might have a bearing on his or her clinical judgment? The disclosure of potential conflicts of interest at least assures patients that their physician is cognizant of biases that might compromise care, and some might find that reassuring.

I would go further, however. For me, the very need to disclose a potential conflict of interest signifies immorality. Convictions of right and wrong are emotion laden. If I do something I find morally wrong, I feel shame or guilt. If you do something I find morally wrong, my sentiment of disapprobation is equally visceral, ranging from disappointment to outrage. Let me be clear: there is an important distinction between moral judgments and conventional judgments. Guidelines for acceptable conflicts of interest are an exercise in conventional judgment, about which I can countenance debate. However, the following syllogism expresses my moral judgment.

Figure 1. Promotional spending by type of marketing activity, 1989 to 2008 (in billions of dollars). The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) issued an “Economic and Budget Issue Brief” on December 2, 2009, regarding “Promotional Spending for Prescription Drugs.” These data were obtained from SDI, a company that collects and sells information about the pharmaceutical industry. The SDI data set is not all-inclusive. However, the trends in the different categories are telling.

compromise trustworthiness in any treatment act.

Given my stringent, intensely personal sentiment, it has been decades since I have acquiesced to being “detailed” by pharmaceutical representatives, let alone allowing “samples” to be part of my practice. The hardware sales force has limited interest in this rheumatologist, and I have none in them. I shun all sorts of “freebies,” and I have no interest in participating in any industry-supported educational undertaking where my participation might promote a hidden agenda on the part of the sponsor. In my practice, I have no conflicts to declare and no need to declare their absence. Furthermore, there is no need for any physician who shares my moral judgment to declare a conflict of interest. The absence of such is a given.

The seeds of these particular moral judgments were planted in my youth by my father as I accompanied him on house calls, and they germinated when I worked in proprietary hospitals half a century ago. I have had lapses, and I have been fooled on occasion. But these moral judgments have accompanied me on every patient contact for forty-five years.

Are they anachronistic? Am I a Luddite?

Medicine is no longer a cottage industry; it is a complex industrial enterprise. Medicine’s front line, whatever it is called and whoever embodies it, is blurred. Physicians march to many drums, many of which demand a degree of fiscal savvy if not the occasional quick step. Could one argue that the modern physician is a match for whatever marketing biases might distort the message of pharmaceutical “detailing” and for agendas that might slant other educational events? Whose prescribing habits are influenced by the convenience and putative beneficence of drug samples, let alone by participation in flawed drug trials or marketing exercises masquerading as drug trials? What physician’s clinical perspective can be bought with pizzas or trips to Monte Carlo? Isn’t it insulting to suggest such? And doesn’t the implication that the accompanying gifts and other largesse are forms of bribery aggravate the insult?

Of course it does. And so it should. In 2005 Minnesota officially limited pharmaceutical gifts to $50 per physician per year, effectively eliminating lunches and much else, including whatever physicians found appealing about meeting with pharmaceutical sales representatives and going to sponsored programs. The Massachusetts legislature banned direct marketing of pharmaceuticals and devices to providers. (The state can’t touch direct-to-consumer advertising since the U.S. Supreme Court deemed it an example of freedom of speech.) However, the Massachusetts legislature is thinking about rescinding the ban because of pressure from Massachusetts’s businesses, which claim to have suffered because medical conventions and other medical-marketing venues have found other states more accommodating.

Is this much ado about very little? Not to my way of thinking. Disclosure by the practitioner is nothing but a symptom of the pernicious ethos we will examine in greater detail shortly. The profession I love has been enveloped in a cloud of conflicting interests. The opinions of “thought leaders” are valued and rewarded by the purveyors advantaged by these opinions. Surgeons and other interventionalists are similarly rewarded by purveyors of the widgets and gizmos these physicians are wont to advocate. Professional societies appear more and more like industry subsidiaries and professional meetings more and more like market days. “Academic health centers” and similar large medical institutions seem more interested in “throughput” and supping at the “translational research” troughs than in valuing bedside excellence. And all this is sanctioned, even applauded, by oversight bodies. The FDA has no constraints on the consultancies of advisers, medical journals find “declarations” of conflictual relationships to be cleansing, academic health centers bid for drug trials to fuel their “translational” profit centers, and interventionalists are coddled if they regale the uninitiated with their technological prowess. The ethos is so entrenched that even the patients of spine surgeons see no problem if they are offered a device purveyed by a manufacturer for whom their surgeon is a paid consultant.

Well, I see a problem for which no degree of disclosure is a match. The only match is for the members of my profession to learn to wear, with pride, the moral judgments I detailed above and to decry the behavior of any physician not so inclined. Disclosure should not seem necessary, and it is never sufficient. For the Citizen Patient, it is a red flag.

The Disclosure Dodge in the Medical Literature

“Industry” is not a curse word. Industry is the fountainhead of jobs that sustain and nurture all of us directly or indirectly. Furthermore, relationships between industry personnel and professionals not employed by industry are not necessarily wrong, let alone evil. To the contrary, such relationships can enhance the productivity of both parties. The challenge for the independent professional, whether based in the academy or not, is to guarantee that the relationship does not distort or compromise that professional’s primary role as educator, physician, therapist, clergy, or whatever.

On what can one base such a guarantee? In medicine, the professional is recruited to the task by an industry that seeks to be advantaged by that professional’s expertise and is willing to reward the professional with influence, money, or other barter. The professional is always marching to two drums, one that beats for industrial success and another that beats for the benefit of the patients who are the primary responsibility. I am willing to call a halt to such arrangements whenever there is the possibility that marching to industry’s drum can compromise the care of the patient or the education of those involved in that care.

That is not the consensus today, nor is it common practice. The consensus is that judgment regarding any compromise should be passed on to the interested observer—the reader, the audience, the grant reviewer, and the like. This is accomplished by disclosing the potentially compromising relationship on institutional forms, during public presentations, and as appendages to any professional publications. Many publications, particularly those that involve pharmaceuticals and medical devices, have long lists at the end detailing potential conflictual arrangements of the authors, such as paid consultancies, grants from purveyors, and equity positions. Among such authors, there seems to be a certain pride when one’s list is longer than another’s.

How about all the editorialists? Journal editors invite physicians to write editorials designed to put a particular research paper into a broader context than the authors do in the discussion of their results. The editorialists are chosen because they are respected for their contributions to this particular research area and because they can be counted on to say something interesting. I can tell you from many such experiences that it is a challenge to find an appropriate footing between destructively critical, excessively exuberant, and unnecessarily self-referential. It is the last tendency that represents my conflictual challenge, since I have done all I can to eschew formal external conflictual relationships. What about the editorialist who has more than purely intellectual conflicts of interest lurking between the lines? Is disclosure of financial and other entanglements enough to enable the reader to accept the editorial as a sage guide to the research under consideration? The editorial board of one prominent journal, the New England Journal of Medicine, thought not. But then they went on to the absurdity of quantifying in monetary terms the degree to which conflictual relationships might compromise sagacity. If the editorialist was compensated more than $10,000 in any given year by any entity the editorialist deems relevant, recusal should follow. The editorial board argued that there had to be some leeway or they would have difficulty identifying any nonconflicted editorialists. This argument is in keeping with policy statements by the National Institutes of Health and the American Association of Medical Colleges. I find it a reproach at so many levels, not the least of which is to the principle of peer review. It suggests that peer review is for sale, and it is relatively cheap.

Is anyone reassured by all this disclosing? I am not. To the contrary, I look askance at disclosers and at the substance that is being put forth in editorials or research papers by these compromised authors. And I look askance when clinical investigators disclose financial arrangements with for-profit enterprises that contract them to study the benefits patients might derive from their products. I am not surprised when study after study documents that when the assessment of a drug or device is industry supported, the result is far more likely to be positive than when the assessment of the same drug or device is government supported. I am not surprised by studies that demonstrate similar bias when an editorialist has some financial arrangement with the topic of the editorial. Disclosure be damned; give me uncompromising ethical behavior.

But that doesn’t mean that the divide between industry and nonindustry scientists is inviolate. If professionals based in industry and professionals based in governmental or nonprofit organizations feel the need to interact at a professional level, there are venues that are meant to foster such interchange, including professional meetings and publications. Many a “blockbuster” drug has been developed because industry scientists took advantage of openly disseminated insights that were generated by nonindustry scientists supported by governmental research grants. One might wonder about the equity of a system in which the taxpayer contributes both to the pharmaceutical firm’s profit margin and development costs. But the interchange itself is a testimony to the ethical nature of the scientific process, an ethic that values peer review and transparency. Neither peer review nor transparency—transparency in particular—comes naturally. In both the private and public arenas, transparency is usually restrained and peer review often distorted by the competitive nature of scientific practice. The desire to be the first to do something is ingrained. Primacy is certified in the private sector by patent or licensure and rewarded by a competit...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- The Citizen Patient

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. Shills

- 2. Price Fixing

- 3. Truth and Consequences

- 4. If We Build It, They Will Come

- 5. Another Good Idea Still in Waiting

- 6. The Social Construction of Health

- 7. Extricating Health Care from the Perversities of Its Delivery System

- 8. A Clinic for the Twenty-First Century

- Conclusion

- Index