![]()

Chapter 1: Growing Up Absurd

From Granville Summit to State College, 1914–1932

“My Uncle Bill once told me that I was born a mistake” was the way Vance Packard thought he might begin his memoirs. Given the seven years since the birth of his older brother and what we know of family planning in the early twentieth century, his Uncle Bill was probably right when he told his nephew that his birth was unplanned. Yet even if what his uncle said was not true, hearing him say it strengthened Packard’s perception of himself as an anomaly. The sense that he was an outsider not only reverberated with critical childhood experiences but also influenced the career he later chose and the drive with which he pursued it. At times, he pictured his early years as an idyll that Norman Rockwell might have painted, but, as he recognized, the real situation that he and his family faced was more troublesome.

Throughout his life, Vance Packard remained uneasy in his relationship to worlds he entered. Awkward in his presentation of self and having what he later called an “under-integrated personality,” he conquered what he saw through observation, not participation.1 Driven to earn recognition, he nonetheless remained skeptical about the rewards that success would bring. Opposing the spread of commercialism, he achieved success in the marketplace through his writing and real estate investments. Promoting self-realization, he remained dedicated to a moral vision of community responsibility for social well-being. He saw himself as a rebellious nonconformist, yet this characterization missed how deeply his life was embedded in and helped transform American society.

Childhood in Granville Summit

Born on May 22, 1914, in Granville Summit, Bradford County, Pennsylvania, Packard spent his early years as what he later called a “backwater farm boy” on his parents’ farm in the north central part of the state.2 During his youth, the population of the area declined as local residents left to seek opportunities elsewhere. The villages of Granville Township provided the focal points of local activity, containing as they did the elementary school, the Grange hall, the Methodist church, a store, a milk station, and a railhead. Farming in the area, remarked the authors of a report published in the year of Packard’s birth, “presents difficulties and problems,” stemming mostly from poor soil and hilly land.3 The area was isolated: Canton and Troy, the nearest small towns, were about seven miles away, and the Packards rarely traveled the thirty miles to Elmira, New York, the closest small city. Packard’s paternal ancestors had probably come to Massachusetts from England in 1638; the family moved to Bradford County in the early 1800s. By the time Vance was born, his father’s relatives owned much of the land in the township, with patterns of settlement and marriage combining to make community and kin inseparable. As Packard came of age, the more successful of his male relatives, remembered by him as “jovial achievers,” were just beginning to gain a foothold in the middle class as farmers and small town businessmen.4

Born and raised in Granville Township and with only an eighth-grade education, Packard’s father, Philip J. Packard (1879–1963), initially earned a living by transporting animals, logging timber, and shoveling coal. In 1902 he married Mabel L. Case (1881–1962), and they soon purchased their own farm, an older brother having inherited the family property. Before she agreed to wed, Mabel insisted that Phil give up drinking alcohol, chewing tobacco, and chasing women.5 Moral reformation and the bonds of matrimony turned him from a rambunctious young man into a model husband and an amiable, well-respected citizen. As a father, Phil Packard was a disciplinarian, punishing his children physically with firmness but without rancor. Vance Packard later noted his own “proneness to inappropriate behavior,” something that emerged most clearly when he played childhood pranks. In response came “thunder and lightning” from his father. As his son recalled, “He’d holler and I’d jump.”6

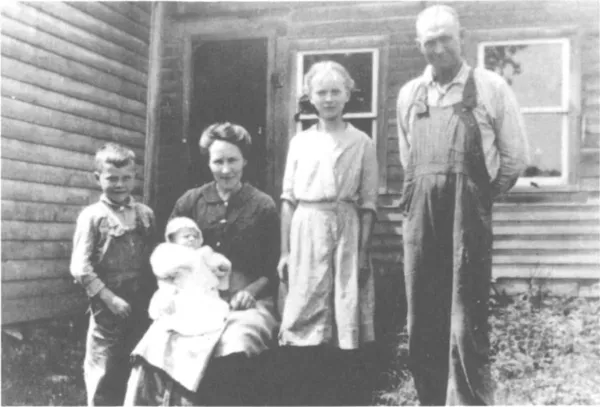

Packard family outside their farmhouse in Granville Summit, shortly after Vance’s birth, 1914. From left to right: LaRue, Vance, Mabel, Pauline, Philip. (Used by permission of Vance Packard.)

Mabel Case grew up in an orphanage, where she received a high school education. At age seventeen, she began her career as a public school teacher. Vance Packard saw little of his mother’s family, few of whom lived near Granville Summit. Those who did live close by were poor, barely respectable, and “somber.”7 Within the home she was very much the austere schoolmarm—“an aloof, tense person of rectitude,” her son remembered, someone who probably saw her son “as a special challenge posed by the Lord in His Wisdom.” She played the piano at the local Grange and the organ at the Methodist church, where she also taught Bible classes. A genteel lady who faced unladylike conditions on the farm, she constantly strove to uphold standards of decorum. “Dad wanted to be a farmer,” Vance Packard’s sister later remarked, “Mom didn’t want to be a farmer’s wife.” As one of the better-educated people in the local community, Mabel Packard looked down on farming. Instead, she sought education for Vance and for his two siblings, Pauline and Charles LaRue, who were respectively ten and seven years older than their brother. With “a strong drive for Culture,” she “dug deep,” her son recalled, “into our skimpy funds to pay door-to-door salesmen for sets of encyclopedias and classics.” She endowed Vance, her favorite child, with the sense that books were stepping-stones over which he could move to a world beyond the confines of his social and geographical lot.8

Like other women who had taught school before they settled down to the life of a farmer’s wife, Mabel Packard felt trapped. She enjoyed few worldly pleasures, lived with a keen sense of isolation, and faced a continual round of chores. Her social aspirations exceeded her ability to achieve them, and she believed she was superior to most of the women she encountered. In a world where bloodlines were so central, she found herself caught in the web of her husband’s extended family. She had to live within a family context, yet as an orphan and as a woman in the midst of her husband’s world, embedding herself in a kinship network was problematic. Unlike her peers, she entered local social worlds principally through connections she inherited from her husband, not through ones she herself initially established.9

Phil Packard had more reason to be satisfied with his lot. An outgoing man who lived in a community filled with his relatives, he felt very much at home. The division of labor on the farm enabled him to accord Mabel the respect she deserved. He provided his family with a modicum of comfort, purchasing their first new car in 1922. Simple and small, their five-room home lacked central heat, an indoor bathroom, and electricity. As a youth, Vance Packard remained unaware of whatever problems the ups and downs of the economy posed for the family. There was always enough food on the table, much of it produced on the farm. Hard work on their 105 acres yielded income from the grain raised on the few fertile stretches of land, the lumber cut from the woods, the milk taken from the dozen or so cows that grazed on the hillsides, the eggs laid by the chickens, and the sale of animal skins.10

Beyond the household, life centered on extended family and local institutions. The Packard kids did the kinds of things farm children in the region had done for generations—invented games, trapped animals, gathered maple sap from the trees, and rode horses to the village school. On Saturdays, the Packards went to meetings and family gatherings at the Grange hall. On Sundays they traveled to the Methodist church, where both parents were active members and where the children attended Sunday school. Genuinely religious, Phil and Mabel studied the Bible and punctuated their days with prayer. Doing their best to lead Christian lives, they supported temperance and missionary work.11 Occasionally, members of the household had contact with the world beyond the township. The train stopped not far from the farm to pick up milk and to take Pauline to high school and, later, to a teacher training college.

People like Vance Packard’s parents shared a set of assumptions about how to live. Phil took care of the cows, the animal skins, the barn, and the land. Mabel tended the house, the garden, the chickens, and the children.12 Despite considerable separation of work into masculine and feminine spheres, the household derived a sense of cohesion from cooperation rather than from equality. The divided responsibilities, quite common for farm families in which there was some aspiration to middle-class standing, ensured that physical effort would not exhaust the wife. Yet unlike their urban middle-class peers, rural women such as Mabel Packard constantly interacted with their husbands. Husband and wife shared a sense that her education and his identity as a yeoman made them superior to those who had neither a high school degree nor the independence of a farmer. Her role as a civilizing mother helped ensure that the children would turn out to be something other than farmers and that Mabel would secure the honor that both partners felt she deserved. The commitment to the female virtues of piety, purity, and domesticity made sure that husband and wife recognized what governed public behavior. In community affairs, the spheres in which they operated were both segregated and overlapping. Phil’s world beyond the home revolved around the Farm Bureau and, later, the Dairymen’s League; Mabel’s, around the Sunday school, Ladies’ Aid Society, and support of missionary work. Yet they participated together in the Methodist church, the Grange, and even in activities sponsored by local women’s organizations, especially those that supported Prohibition.13

In works published as an adult, Vance Packard evoked the pleasures of life in Bradford County. In 1972, he wrote of meeting “people as families at Grange Hall suppers on Saturday nights.... at church festivities, at cattle auctions, at the milk station, at the icehouse pond, and at the contests on the steep road leading to Granville Summit on Sunday afternoons.” Similarly, he celebrated the inclusiveness of the community where he spent his early years. Everyone, he remarked in 1960, “regardless of age or economic status, used to go to these socials: the blacksmith, the storekeeper, the farmers big and little, the farm hands and all their children.” When he talked about the pleasure he derived from contributing to the family’s well-being by tending skunk traps and cleaning the henhouse, he contrasted the simple, productive work on a farm early in the century with more modern and alienating conditions found in American cities, suburbs, and large corporations fifty years later.14

The experiences and memories of the world in which Packard spent his early years provided a set of values that shaped his career. Although as a writer he romanticized the conditions that obtained during his childhood, much of his later critique of mid-century society came from his own heartfelt assessment of the virtues of the life he left behind. In similar farm communities the lines between men and women were clear yet intersecting. With family, kin, and community integrated, there was little room for unbounded individualism. Because people relied on hard work more than on superficial symbols of social class, a rough egalitarianism held the community together. People bought and sold goods and services, but they did not systematically use market yardsticks to judge people’s worth. Day in and day out, they understood the human and concrete dimensions of work. They depended on products they themselves made or purchased, items that they rarely imbued with qualities they did not inherently have. Husbands and wives, parents and children, farm owners and neighbors worked together as partners, without relying excessively on the exchange of money or experiencing sharp social divisions. Middlemen, speculators, immigrants, and African Americans, though present in the county in small numbers, were beyond the pale in the stories farm people commonly told about their own lives.15

Threats to the Pastoral

Tragedy, however, intervened in this idyll. Vance later remarked that Mabel Packard, deeply dissatisfied with being a farmer’s wife, at times seemed on the verge of a nervous breakdown. Phil Packard, though more content with his own lot, did not adjust easily to some of the changes modern life brought. Once, having tried to stop his car by yelling “Whoa” instead of using the brakes, he sat in the automobile as it crashed through the garage. Vance Packard knew relatives on his mother’s side who had difficulty with alcohol or mental illness. During World War I, an aunt, who had married a German American and lived in Elmira, was subjected to attacks on her family as “Huns.” As a result, her husband lost his job. In the early 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan burned crosses on the hills in the township in order to intimidate Roman Catholics in Troy.16

Packard grew up acutely aware of the difference between insiders and outsiders. He did not know that Roman Catholics were Christians, and he did not meet one of them until he moved away from the county. His first encounter with an African American was within a context fraught with drama and racism. At the annual fair in Troy, the locals played a game called Hit the Nigger on the Head, in which they would win a prize if they could throw a baseball and hit a black man’s face that stuck out from a hole in a white sheet. Mabel Packard dragged her son away from the scene, remarking that it was denigrating to black people. What Packard remembered as his “first big philosophic thought” also involved a contrast between the familiar in Granville Summit and the strange in the world beyond. Walking by himself one day when he was seven or eight, he remembered his parents’ talk of India. “I could understand outposts such as Troy, Canton, Towanda,” he recalled, “but India left me shaking my head.”17

During Packard’s youth, economic changes that originated beyond the boundaries of Bradford Country set off bitter fights among local residents.18 New methods of transporting and storing milk had opened markets in cities up to three hundred miles away. Powerful monopolistic corporations gained control over milk distribution and threatened the independence and economic well-being of dairy farmers. Organizing themselves into a marketing cooperative called the Dairymen’s League before World War I, most of the farmers in the region strongly opposed Sheffield Farms, a powerful, privately owned distributor. In these years, members of the league articulated a vision that contrasted greedy middlemen and monopolistic corporations with virtuous farmers whom they envisioned as real producers struggling so they could live a simple life and prevent corruption of the commonwealth. Though some dairymen remained skeptical of coordinated action because it smacked of trade unionism and they feared it might undermine their independence, many banded together to fight corporate monopolies and protect their own interests.

Disagreements divided communities. Neighbors hurled the epithet “scab,” dumped milk on its way to market, fought at the creamery, and stopped speaking to one another altogether. Phil Packard, a longtime member of the Grange who had helped bring the Dairymen’s League to the county, considered the struggle against the distributors, his son recollected, a “great moral battle.” As a child, Vance Packard heard discussions about the conflict between the league and Sheffield Farms, a bigger topic of conversation, he recalled, than ...