- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

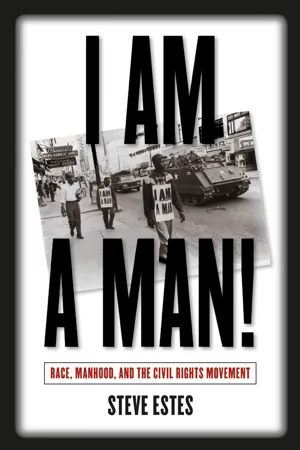

The civil rights movement was first and foremost a struggle for racial equality, but questions of gender lay deeply embedded within this struggle. Steve Estes explores key groups, leaders, and events in the movement to understand how activists used race and manhood to articulate their visions of what American society should be.

Estes demonstrates that, at crucial turning points in the movement, both segregationists and civil rights activists harnessed masculinist rhetoric, tapping into implicit assumptions about race, gender, and sexuality. Estes begins with an analysis of the role of black men in World War II and then examines the segregationists, who demonized black male sexuality and galvanized white men behind the ideal of southern honor. He then explores the militant new models of manhood espoused by civil rights activists such as Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr., and groups such as the Nation of Islam, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and the Black Panther Party.

Reliance on masculinist organizing strategies had both positive and negative consequences, Estes concludes. Tracing these strategies from the integration of the U.S. military in the 1940s through the Million Man March in the 1990s, he shows that masculinism rallied men to action but left unchallenged many of the patriarchal assumptions that underlay American society.

Estes demonstrates that, at crucial turning points in the movement, both segregationists and civil rights activists harnessed masculinist rhetoric, tapping into implicit assumptions about race, gender, and sexuality. Estes begins with an analysis of the role of black men in World War II and then examines the segregationists, who demonized black male sexuality and galvanized white men behind the ideal of southern honor. He then explores the militant new models of manhood espoused by civil rights activists such as Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr., and groups such as the Nation of Islam, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and the Black Panther Party.

Reliance on masculinist organizing strategies had both positive and negative consequences, Estes concludes. Tracing these strategies from the integration of the U.S. military in the 1940s through the Million Man March in the 1990s, he shows that masculinism rallied men to action but left unchallenged many of the patriarchal assumptions that underlay American society.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access I Am a Man! by Steve Estes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politica e relazioni internazionali & Diritti civili in politica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Man the Guns

I spent four years in the army to free a bunch of Frenchmen and Dutchmen, and I'm hanged if I'm going to let the Alabama version of the Germans kick me around when I get back home. No sirreee-bob! I went into the army a nigger; I'm comin’ out a man.

–Black corporal, U.S. Army (1945)

–Black corporal, U.S. Army (1945)

Shells from a Japanese cruiser streaked across the bow of the USSGregory as Ray Carter rushed to his battle station. The Gregory was supporting the American invasion of Guadalcanal in the midst of a bloody island hopping campaign to retake the Pacific from the Japanese during World War II. Ray Carter was the “hot shell man” for a four-inch deck-gun on the Gregory. He wore asbestos gloves in order to catch the white-hot shell casings ejected from the gun. Suddenly, one of the Japanese cruiser's shots landed a devastating hit on the Gregory, killing the American captain instantly and crippling the vessel. A surviving officer ordered all hands to abandon ship. “I donned a life jacket,” Carter later remembered, “and took a running jump, landing as far out as possible from the ship.” Like his fellow sailors, Carter scrambled onto one of the life rafts. The men looked back and watched as the Gregory sank beneath the waves. Feeling lucky to be alive, Carter talked about the bond that formed between the men. “Talk about togetherness; we were straight out of The Three Musketeers, all for one and one for all.” Such combat-forged camaraderie is a common theme in stories from the “Good War.” Yet it does not tell the whole story of Raymond Carter's wartime experiences or the experiences of other black men and women who served during World War II.1

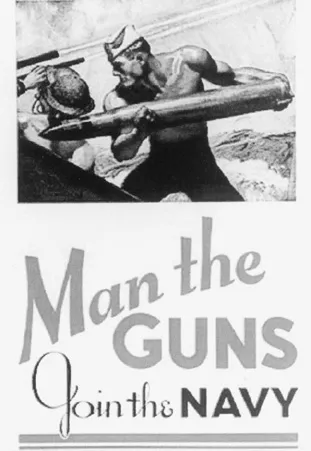

Ray Carter enlisted in the Navy early in the 1940s as a fresh-faced nineteen-year-old from Detroit, Michigan. Perhaps he had seen a poster urging young recruits to “Man the Guns” or one featuring a pin-up girl that read, “Gee, I wish I were a Man!! I'd join the Navy.” More likely, posters and newspaper stories featuring the black World War II hero, Dorie Miller, inspired Carter to sign up. Miller was a messman on the USSWest Virginia stationed in Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. During the Japanese surprise attack that morning, Miller risked his own life to drag his dying captain from harm's way, before manning a deck-mounted machine gun. Though he had not been allowed to train on the weapon because of his race and rank, Miller took aim at Japanese planes until a fire on the deck drove him from his position. Likely hoping to follow Miller's example and to man the guns himself, Ray Carter joined the Navy.2

Because of his tan complexion, the Navy recruiter asked Carter about his nationality and was clearly surprised when Carter responded that he was “colored.” The white officer quickly crossed out Carter's original duty assignment and wrote “steward” on the recruiting forms. It was official policy of the Navy in the early 1940s that “colored men are enlisted only in the messman branch” as cooks and personal attendants for white officers. It was a “waste of time and effort,” the Navy reasoned, to recruit and train black sailors for other positions that were assumed beyond their capacity. Carter wondered why the Navy issued white coats in addition to normal uniforms for himself and the other black recruits. “Oh man, was I a real dum-dum!” he later exclaimed with a mixture of humor and sadness. “I had enlisted to fight for my country and my great contribution to the war effort was to wait on whites.”3

More than one million African Americans served in the U.S. Armed Forces during World War II, and hundreds of thousands more contributed to the war effort in war-related industries. Though many black soldiers were relegated to labor battalions in the early years of the war, manpower needs and political pressure eventually brought thousands of them into combat. Similarly, many war industries had initially hired white men only. As white American men went off to war, however, positions began to open up for white women and African Americans. Scholars of the war argue that these changes in domestic race and gender relations were “central to the whole campaign for civil rights” in the 1950s and 1960s. Previous studies of the war have explored how Rosie riveted a new identity for women and how the Tuskegee Airmen earned the movement its wings. This chapter investigates the ways that World War II altered conceptions of African American manhood and how these changes set the stage for the civil rights movement.4

Although it is certainly not the only defining experience for boys becoming men, military service—especially during a time of war—has traditionally been viewed as a rite of passage into manhood. In the context of wartime service, “man” becomes not just a noun but a verb, not just an identity but an action, as soldiers and sailors are ordered to “man the guns.” Military action, then, shapes a masculine identity. The tests of physical prowess, courage, and mettle in the military are supposed to harden young boys into men, to prove that they can fulfill their traditional roles as husbands and fathers, protecting their families and communities from harm. On a political level, wartime military service has also been seen as an obligation of citizenship in modern republics and democracies. Citizen-soldiers must protect and defend the state in return for the right to have a say in how the state is run. Well into the twentieth century, the segregation of the armed forces and the relegation of women and minority men to noncombat roles excluded them from this band of brothers, for this was where manhood and citizenship were defined. Still, there was a sense among African American men that participation and valorous service in war could uplift their race and gain them respect and recognition as men. Such had been the case during the Civil War, when nearly 200,000 black soldiers fought in combat and 300,000 African Americans labored behind the lines for the Union Army. Black military service helped to inspire passage of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution, ending slavery and laying the groundwork for Reconstruction. Yet these rights had been rolled back in succeeding decades, despite evidence of African American patriotism during the Spanish-American War and calls by black leaders like W. E. B. Du Bois for Americans to “close ranks” and share the burden of battle in World War I. It seemed that the political and social legacies of black heroism and martial manhood had a limited half-life when the military crisis of the moment had passed. Understanding that their civil rights had been curtailed rather than expanded after these conflicts, black men and women exhibited deep ambivalence at the outset of World War II. Navy steward Ray Carter continued to feel this ambivalence when he spoke to an interviewer more than two decades after the war in the midst of the civil rights movement. He wondered how “I or my people benefited from the time I spent in the service and the insults and humiliation I endured as a man.” But one legacy of his service was clear. When asked what he thought about young militants in the civil rights movement, he said that he was proud of them. “After all,” he explained, “they were sired by the men of World War II.”5

Even before the attack on Pearl Harbor brought the United States formally into the war, the battle lines were drawn at home. Industries in the United States began gearing up for war production in 1939, and in 1940 President Franklin D.

McClelland Barclay's recruiting poster for the Navy entitled “Man the Guns” (1942) emphasizes the manly duty to serve with its arresting image of a muscular white seaman ramming home a shell in the midst of battle. David Stone Martin’s “Above and Beyond the Call of Duty” (n.d.) foregrounds the loyalty of black seaman Dorie Miller against the abstract backdrop of Pearl Harbor without explicitly showing Miller's heroic action or his assigned role as a messman. Miller received the Navy Cross only after much pressure from the NAACP and the black press. Still Picture Branch (NWDNS-44-PA-24 and NWDNS-208-PMP-68), National Archives and Records Administration.

Roosevelt began shipping arms to aid the British in the fight against Germany. After the record unemployment of the Great Depression, employers in these burgeoning war industries could pick and choose their workers. In the second half of 1940, white unemployment declined from nearly 18 percent to 13 percent, but black unemployment in this same period remained at an astonishing 22 percent. In the immediate wake of the Pearl Harbor attacks, less than three percent of the workers in American defense industries were African Americans, and many of these black war workers were relegated to low-paying, unskilled positions. “While we are in complete sympathy with the Negro,” one executive at the North American Aviation Company explained, “it is against company policy to employ them as aircraft workers or mechanics. . . . There will be some jobs as janitors for Negroes.”6

Black labor and civil rights leaders pressured the government to deal with rampant workplace discrimination. Black trade unionist A. Philip Randolph came up with the idea for a March on Washington in 1941. Backed by Walter White of the NAACP, and other black leaders, the march would protest racial discrimination among defense contractors, federal agencies, and the armed forces. “If American democracy will not insure equality of opportunity, freedom and justice to its citizens, black and white,” Randolph argued, “it is a hollow mockery and belies the principles for which it is supposed to stand.” The blues singer Josh White put it even more simply in “Defense Factory Blues”: “Well, it sho’ don’ make no sense, when a Negro can't work in the National Defense.” Initially planned for 10,000 people, Randolph predicted a few weeks before the scheduled date of the march that more than 100,000 African American protesters might come to the nation's capital. This was no empty threat. Randolph could count on the support of the militant followers in his powerful union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, as well as thousands more demonstrators organized by local March on Washington committees in cities across the country. President Franklin D. Roosevelt met with black leaders in the summer of 1941 to try to persuade them to drop their demands. He was unsuccessful. A few days after the meeting, the president issued Executive Order 8802, which forbid racial discrimination by employers and labor unions working with defense contracts and also set up a Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) to investigate racism in war industries. Randolph called off his march, but he would go on to lead an even greater pilgrimage for jobs and freedom two decades later.7

During the early 1940s, despite a small staff and an unenthusiastic southern chairman, the FEPC held hearings around the country, examining the hiring practices of various defense contractors. Earl Dickerson, an outspoken black insurance man and politician from Chicago, served on the FEPC and remembered heading to Los Angeles for hearings early in the war. The aviation contractor Lockheed had around 20,000 employees in southern California, only nine of whom were African Americans. When Dickerson asked where the black employees worked and how long they had been with the company, the Lockheed spokesman sheepishly admitted that they were all janitors, who had been hired just before the hearing. Without the political clout to enforce the president's nondiscrimination order, the FEPC could do little more than slap companies on the wrist with warnings. Integration would come to the defense industries, but only after millions of white men were shipped overseas to fight in the war.8

The American military faced an even more delicate task of recruiting minorities while still trying to maintain racial segregation. Despite the heroism of black soldiers in World War I, there still were doubts among top military officials about the combat capabilities of African Americans. A 1925 study conducted by what is now the Army War College based its conclusions on the tenets of social Darwinism: “In the process of evolution the American Negro has not progressed as far as the other subspecies of the human family. . . . His mental inferiority and inherent weakness of his character are factors that must be considered . . . [in] any plans for his employment in war.” Such assumptions were still widely held by military brass at the outset of World War II, but political pressures led to gradual policy adjustments that opened the door for more black military participation. Fearing a challenge from Republicans for black votes in the 1940 elections, FDR and some liberal Democrats crafted a Selective Service Act, calling for “any person, regardless of race or color” to be included in the draft and be given the opportunity to enlist voluntarily. So as not to ruffle the feathers of white southern Democrats and military leaders, however, the White House and War Department quickly assured the public that such legislation would not jeopardize the military's policy of racial segregation, which had “proven satisfactory over a long period of years.”9

To African Americans, Washington's Jim Crow pronouncements whispered the same white supremacist dogma shouted by Adolph Hitler and the fascist Nazi Party in Germany. In Mein Kampf, Hitler had outlined conspiracy theories based on anti-Semitism and racism to explain the depressed state of the German economy after World War I. “It was and it is the Jews who bring Negroes into the Rhineland, always with the same secret thought and clear aim of ruining the hated white race,” Hitler warned. In his eyes, the men of these “bastard” races presented a clear danger to German womanhood and the German nation. Yet denigration of other races was only half of the Nazi propaganda strategy. Idealization of Aryan manhood and athleticism were just as central to the Third Reich. Hitler and his followers viewed the 1936 Olympics in Berlin as a perfect opportunity to showcase German superiority. When black track star Jesse Owens raced to victory and four gold medals in the Berlin games, the Nazis’ white supremacist theories took a beating. Two years later, African American boxer Joe Louis knocked out the German champ Max Schmeling, deemed the embodiment of Aryan manhood, in the first round of a heavyweight title bout. Yet when conflict came with the United States, Hitler continued to harp on Jewish and black inferiority, reportedly telling his senior staff that Germany would surely defeat the “half Judaized, and the other half Negrified” American people.10

The declaration of war in the United States brought a rush of enlistments, a draft, and calls to arms based on the obligations of citizenship and manhood. For young white men, service in the armed forces during World War II was a chance to prove themselves. Bob Rasmus, a white Chicagoan who volunteered as an infantry rifleman, explained in an interview years later: “I was a skinny, gaunt kind of mama's boy. I was going to gain my manhood then. I would forever be liberated from the sense that I wasn't rugged. I would prove that I had the guts and the manhood to stand up to these things.” Black servicemen discussed some of the same traditional themes, but with different political implications. Draftee Jack Crittendon explained to the graduating class at his high school why he was proud to serve, recalling Dorie Miller's heroism. “He proved himself capable. And when more black men are given the opportunity to serve their country they will prove themselves worthy of the trust placed in them. Give them a chance, [because] . . . a man is still a man!” Such sentiments gave parents, black and white, cause for concern. When Nelson Peery told his mother that he was enlisting, she steeled herself for the waiting and worrying to come. “I knew you'd go,” she told her son. “I can't stop you. I guess men have to fight to prove something to themselves. It's just that I hate to think that I raised seven sons to become cannon fodder.”11

Not all young black men wanted to fight, kill, and perhaps die in a segregated army, despite the seemingly laudable aims of defeating Hitler and defending democracy. Bayard Rustin, an organizer for the Fellowship of Reconciliation, refused to serve because of his Quaker upbringing and his commitment to the philosophy of nonviolence advocated by Mohandas Gandhi. In addition to political opposition to service in a segregated army, Rustin and other pacifists sought an alternative path to manhood that did not rest on military service or physical aggression. Elijah Muhammad, the leader of the group that would later become the Nation of Islam, opposed the draft not because he disagreed with traditional ideas about martial manhood, but because he felt that the black man's struggle lay closer to home and that his natural allies were the Japanese and other people of color. “The Asiatic race is made up of all dark-skinned people, including the Japanese and the Asiatic black man,” Muhammad explained to his followers, urging them to ignore the draft. “The Japanese will win the war, because the white man cannot successfully oppose Asiatics.” Rustin and Muhammad both served jail time for their philosophical and ideological opposition to the U.S. war effort. Other black men wanted to avoid the war for more pragmatic reasons. Howard McGhee was an up-and-coming jazz trumpeter during World War II. When he was called down to the induction center for a psychiatric evaluation, he asked the army psychiatrist, “Man, why should I fight? I ain't mad at nobody out there. . . . I wouldn't know the difference. . . . If he's white, I'm going to shoot him. Whether he's a Frenchman, a German, or whatever, how the fuck would I know the difference?” As he had intended, that answer got McGhee classified as 4-F, psychologically unfit for service. During the war, he got a chance to join Count Basie's band, replacing a horn player who had been drafted. Afterwards, McGhee explained, “I wasn't ready to dodge no bullets for nobody. And I like America. But I didn't like it that much. I mean it's all right to be a second class citizen . . . but shit, to be shot at, that's another damn story.”12

Rustin, Muhammad, and McGhee were certainly not alone in denouncing the war, but the majority of young black men who were called to serve did so. Still, the armed forces relegated them almost exclusively to labor and service battalions for the first two years of the war. Trained under white southern officers who supposedly “knew the Negro” better than their northern counterparts, 80 percent of black recruits and draftees were stationed at bases in the South, surrounded by communities that were hostile to black men in uniform. John Griffin, a black Marine Corps recruit from Chicago, learned this lesson first hand. The Marines had, in fact, rejected black volunteers for nearly a century and a half after the Revolutionary War, from 1798 to 1941. The Corps only reluctantly began accepting African Americans early in World War II. Even before he arrived for training at the segregated base attached to Camp Lejeune in North Carolina, Griffin faced the humiliation of having to move to the back of a segregated train as it traveled into the South. For much of the war, the commanding officer of the black training facilities at Camp Lejeune was Colonel Samuel A. Woods Jr., a native of South Carolina and an alumnus of that state's all-white military college, The Citadel. According to an official history of black Marines in World War II, Colonel Woods “cultivated a paternalistic relation...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- I AM A MAN!

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction Am I Not a Man and a Brother?

- Chapter One Man the Guns

- Chapter Two A Question of Honor

- Chapter Three Freedom Summer and the Mississippi Movement

- Chapter Four God's Angry Men

- Chapter Five The Moynihan Report

- Chapter Six I Am a Man!:

- Chapter Seven “The Baddest Motherfuckers Ever to Set Foot Inside of History”

- Conclusion “The Heartz of Men”

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index