eBook - ePub

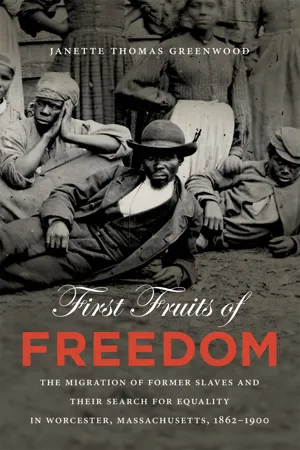

First Fruits of Freedom

The Migration of Former Slaves and Their Search for Equality in Worcester, Massachusetts, 1862-1900

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

First Fruits of Freedom

The Migration of Former Slaves and Their Search for Equality in Worcester, Massachusetts, 1862-1900

About this book

A moving narrative that offers a rare glimpse into the lives of African American men, women, and children on the cusp of freedom, First Fruits of Freedom chronicles one of the first collective migrations of blacks from the South to the North during and after the Civil War.

Janette Thomas Greenwood relates the history of a network forged between Worcester County, Massachusetts, and eastern North Carolina as a result of Worcester regiments taking control of northeastern North Carolina during the war. White soldiers from Worcester, a hotbed of abolitionism, protected refugee slaves, set up schools for them, and led them north at war’s end. White patrons and a supportive black community helped many migrants fulfill their aspirations for complete emancipation and facilitated the arrival of additional family members and friends. Migrants established a small black community in Worcester with a distinctive southern flavor.

But even in the North, white sympathy did not continue after the Civil War. Despite their many efforts, black Worcesterites were generally disappointed in their hopes for full-fledged citizenship, reflecting the larger national trajectory of Reconstruction and its aftermath.

Janette Thomas Greenwood relates the history of a network forged between Worcester County, Massachusetts, and eastern North Carolina as a result of Worcester regiments taking control of northeastern North Carolina during the war. White soldiers from Worcester, a hotbed of abolitionism, protected refugee slaves, set up schools for them, and led them north at war’s end. White patrons and a supportive black community helped many migrants fulfill their aspirations for complete emancipation and facilitated the arrival of additional family members and friends. Migrants established a small black community in Worcester with a distinctive southern flavor.

But even in the North, white sympathy did not continue after the Civil War. Despite their many efforts, black Worcesterites were generally disappointed in their hopes for full-fledged citizenship, reflecting the larger national trajectory of Reconstruction and its aftermath.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access First Fruits of Freedom by Janette Thomas Greenwood in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1 THE GUNS OF WAR

As chattering telegraphs relayed the news of the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter to towns, villages, and cities across the nation, many Americans, both North and South, seemed to welcome the news with a sense of relief. In retrospect, their reaction seems an odd way to greet the opening of what would be the bloodiest war in American history. But for those who had experienced crises that had threatened to rip the Republic apart for decades, the coming of war offered a long-awaited denouement that would finally settle issues fundamental to the future of the United States.

While many welcomed a resolution to sectional conflict, little consensus existed about the meaning of the war in April 1861. Some white southerners saw the war as a necessary fight for independence, a requisite step to protect a distinctive southern way of life built on slavery. Like their Revolutionary forefathers, they viewed a war for independence as a last resort, instigated by years of mistreatment. Others rejected the overblown rhetoric of “fire eaters” and instead viewed the war simply as a defense of hearth and home, especially after Lincoln called for troops to quash the rebellion in the aftermath of the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter. Slaves, drawing on intricate networks of communication that kept many of them abreast of national developments, saw the war as the long-expected and divinely promised vehicle of their liberation.

In the North, most citizens viewed the war as a defense of the Union against wretched traitors who would tear the young nation asunder by arrogantly proclaiming their independence. Abolitionists, on the other hand, while a distinct minority of the northern population, saw the war as a chance to rid the nation of its most egregious sin— slavery. While they disagreed among themselves about how to achieve that goal, they, like slaves in the South, envisioned the end of slavery as the purpose of the war, imbuing the conflict with deep moral purpose and meaning.

“The storm burst and the whole community awakened”

News of events at Fort Sumter catalyzed Worcester County, Massachusetts, as it did the rest of the nation, setting off a frenzy of activities. Thomas Wentworth Higginson, radical abolitionist and minister of Worcester’s Free Church, remembered that “on the day that Fort Sumter was fired upon, the storm burst and the whole community awakened.” As local citizens read the first sketchy reports of the Confederate attack on the morning of 13 April 1861— and two days later learned of Lincoln’s call for 75,000 volunteers to suppress the rebellion— they quickly organized to show their support for the Union cause. Fort Sumter dominated the thoughts and actions of nearly all Worcesterites. The Worcester Daily Spy noted, “The subject is the one controlling, absorbing theme of conversation in all ranks and classes.”1

By the time of the Civil War, ranks and classes proliferated in the city of Worcester as well as in the towns that dotted the county. Situated on the central corridor running from Boston to the east and Springfield to the west, Worcester had emerged, in the words of historian John Brooke, “as a powerful vortex of population, commerce, and public culture, exerting an overwhelming influence on the surrounding region.” Worcester was for many years, as Brooke notes, “only one of a mosaic of towns of roughly equal size” that characterized Worcester County, even though it had been established as the shire town in 1730. But Worcester’s location, combined with its forward-looking town leaders, soon propelled it to the heart of the nation’s budding industrial revolution. Embracing advances in transportation, Worcester merchants forged a link with Providence, Rhode Island, by constructing the Blackstone Canal, which opened in 1828. Only seven years later, the Boston and Worcester Railroad, the first in the nation, accelerated the city’s growth. Other railroads soon followed, elevating Worcester to a regional railroad hub by the 1840s. Whereas many New England towns focused on one industry, particularly textiles, Worcester developed a variety of industries, ranging from textile and boot and shoe production to machinery production and wire works. In 1860, approximately 25,000 people resided in the city, its population exploding by nearly 18,000 in twenty years, as smaller towns in the county declined in population. On the eve of the Civil War, the city boasted 170 manufacturing firms, employing well over 4,000 people, and many Worcester County towns claimed mills and manufactories as well. The war would only accelerate industrial growth as the number of the county’s manufacturing enterprises grew from 1,358 to 1,863 between 1860 and 1870 and capital investment ballooned from roughly $14 million to $34 million. Whereas old Yankee families dominated industrial ownership and politics in Worcester, two waves of Irish immigrants, the canal builders of the 1820s and the famine Irish of the 1840s and 1850s, also called Worcester home. Roughly one of four Worcester residents— approximately three-quarters of them Irish— had been born outside of the United States.2

A day after Lincoln’s call for troops, citizens crowded into city hall to respond to the president’s request. Enthusiastic applause greeted Mayor Isaac Davis’s announcement that two companies of Worcester militia would take up arms immediately in defense of the Union. Other city leaders promised financial support for soldiers and their families, and local ministers and dignitaries addressed the unfolding national events. Unitarian minister Alonzo Hill “caused a deep sensation” when he challenged his listeners to “defend our dear mother country, now so grossly assailed.” With the nation’s capital “threatened by selfish traitors, our young men should . . . defend it to the death.”3

Hill’s interpretation of the war seemed to summarize the prevailing sentiment in Worcester County in April 1861. The war, most seemed to agree, was not about slavery but aimed at maintaining the Union against the treasonous actions of arrogant, hotheaded southerners willing to commit matricide. Even the Worcester Daily Spy, published by abolitionist John Denison Baldwin and one of the most radical daily newspapers in the state, initially framed the nascent war as a war about Union— not about slavery. “It is not the slavery question, in any form,” wrote Baldwin in an editorial, “that is now in issue between the administration and the secession conspirators.” Instead, slavery was “a mere pretext” to foment “the overthrow of republican institutions and the establishment of a despotism in their place.” With the future of the nation at stake, citizens must “forget to discuss the slavery question, and occupy themselves chiefly in discussing treason and traitors.”4

While this was the predominant sentiment in the county, it was not the only one. The crowd that gathered in city hall on the night of 17 April included abolitionists, one of whom, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, spoke at the behest of the crowd. Lured to the city to head Worcester’s radical Free Church in 1852— founded by “comeouters” who left their traditional congregations because of the silence of their churches on the slavery issue— Higginson had led some of the most radical abolitionist causes of the 1850s, including supplying guns and money for John Brown’s attempted slave revolt in 1859. Yet when called upon to speak, the typically loquacious Higginson seemed at a loss for words, explaining that “there was need of no more speaking, after what he heard.” Accustomed to creating divisiveness through his controversial and often illegal activities, Higginson, in April 1861, basked in the fact that “to-night we have more than enthusiasm, we have unanimity.”5

Higginson’s conciliatory remarks, made in the flush of the stunning commencement of civil war, masked not only his radicalism but also the deep antislavery tradition cultivated over several generations in Worcester County. Antislavery activism ran deep and wide in Worcester County. The town of Worcester made its feelings clear as early as 1765 when it charged its representative to the General Court to do what he could “to put an end to that unchristian and impolitic practice of making slaves of the human species.” In 1781, a Worcester County slave, Quock Walker of Barre, successfully sued for his freedom and ultimately helped win emancipation for all slaves in Massachusetts when Chief Justice John D. Cushing of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court found slavery “wholly incompatible and repugnant” to the state constitution’s guarantee of freedom, liberty, and protection of property. In the 1830s, when William Lloyd Garrison helped ignite abolitionist sentiment in the North, antislavery societies mushroomed throughout the county, sponsoring lectures, debates, and meetings all aimed at raising the public’s consciousness about the evils of slavery.6

From the 1830s on, Worcester played a leading role in nearly every major antislavery endeavor of the era. In many ways, Worcester initiated more groundbreaking and radical antislavery activity than its more glamorous counterpart, Boston. Underground Railroad activity was rampant throughout the county, and Worcester served as the destination for numerous fugitive slaves. The city was the birthplace of the Free Soil Party in 1848 and local Free Soil leaders helped found the Republican Party in 1854. That year, T. W. Higginson and Martin Stowell, a local farmer, led a group of abolitionists attempting to free Anthony Burns, held in a Boston prison under the Fugitive Slave Act. A contingent of ten Worcester citizens, armed with axes, provided most of the muscle for the unsuccessful rescue of Burns.7

Also in 1854, after the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, Worcester’s Eli Thayer organized the New England Emigrant Aid Company, recruited the first company of settlers intent on securing Kansas as a free state, and contributed several groups of colonizers— as well as guns— to battle the “slave power” in the West. In the midst of Bleeding Kansas and in the aftermath of the Dred Scott decision, Higginson, along with some radical Republicans and Garrisonian abolitionists, called a “state disunion convention” in Worcester, even though, he noted in retrospect, few were ready “for a movement so extreme.” And when John Brown and his revolutionary band attempted to instigate a slave rebellion at Harpers Ferry in October 1859, Higginson was one of the “Secret Six” who supplied them with arms. Worcester County resident Charles Plummer Tidd of Clinton served as one of Brown’s “captains.” On the day of Brown’s execution in Virginia, several city churches tolled their bells, businesses closed, and citizens held memorial services throughout the county.8

Within days of his conciliatory remarks at the rally in response to Fort Sumter, Higginson questioned his personal involvement in a war that, he feared, did not seek the end of slavery as a stated goal. Offered the position of major in the 4th Battalion Infantry, Higginson refused it, citing his lack of military experience and the ill health of his wife. But above all, he declined the commission because “it was wholly uncertain whether the government would take the anti-slavery attitude, without which a military commission would have been intolerable, since I might have been ordered to deliver up fugitive slaves to their masters,— as had already happened to several officers.” While Higginson later accepted a captaincy in the 51st Massachusetts, “when the anti-slavery position of the government became clearer”— and would go on to lead the Union’s first official black regiment, the 1st South Carolina Volunteers— his initial attitude reflected the ambivalence of many abolitionists at the beginning of the war.9

As the ambiguous nature of federal intervention began to dampen the enthusiasm of some antislavery activists after the first flush of Fort Sumter, others, especially Worcester’s black community, welcomed the war as the long-awaited chance to obliterate human slavery in the United States once and for all. As the white sons of Worcester County and the North rushed to volunteer to fight in the army, the federal government soon made it clear that blacks were not welcome. Nevertheless, local African Americans, like their compatriots across the North, committed their services to the Union cause in a variety of ways. As Worcester’s volunteers readied themselves to depart for Washington, two local black barbers, William Jankins and Gilbert Walker, invited “members of the military companies to call at their hair dressing salons and get trimmed up, without charge, before leaving.”10

Jankins and Walker were among numerous ex-slaves who found refuge in Worcester in the 1840s and 1850s, some of them smuggled into the city “at midnight” by T. W. Higginson himself, where they found refuge at the Tatnuck farm of veteran abolitionists Stephen and Abby Kelley Foster. Like most of their refugee compatriots, they had been born into slavery in the upper South. Jankins had made his way to Worcester after absconding from his master in Virginia. Walker, born a slave in Maryland, secured his freedom through the heroism of his father, whose grateful master freed him after he had saved his master’s son from drowning. Walker’s father subsequently managed to purchase his family members, and Gilbert and his brother Allen Walker ultimately made their way to Worcester. Others, like Isaac Mason, a fugitive from Maryland, and his wife, Anna, came to Worcester via Boston through abolitionist networks linking the two cities. Mason worked as a ditch digger, a farmhand, and a woodcutter on the estates of several prominent white Worcesterites.11

By 1850, Worcester was home to approximately 200 people of color, in a city of about 17,000 people. The community consisted of a mix of northern-born African Americans, people of both Native American and African American descent, and southern-born fugitives. Jankins had already established a flourishing barbering business in Worcester by 1850. Walker, who initially worked as a coachman for a manufacturer, married a local woman of Native American descent and parlayed a state land grant that she received into a thriving barbering business at the prominent Bay State House.12

But in 1850, even the seemingly safe bubble of Worcester was punctured by the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law that October. Part of the Compromise of 1850, the law was one of several agreements made between North and South aimed at averting disunion over the admission of California as a free state. A major concession to the South, the legislation now placed the weight of federal law, and the aid of U.S. marshals, behind southern slaveholders who wished to recover their runaway property in the North. Whether runaway slaves or free born, blacks accused of being runaways— based on a physical description— and taken to court were forbidden to testify on their own behalf or show any documentation to prove their identity or status. Moreover, the law threatened fines and imprisonment to those who aided runaways. The Fugitive Slave Law, in the minds of many northerners, now made all of the nation’s citizens complicit in the institution of slavery.

Worcesterites responded angrily, and the city’s black residents felt especially incensed as the law severely diminished their already fragile freedom. Local citizens jammed into city hall “almost to suffocation” to denounce the Fugitive Slave Law in October 1850. “White and colored, bond and free,” residents of all backgrounds and positions rallied to “preserve the Soil of Massachusetts, sacred to freedom.” While prominent whites attempted to take charge of the meeting, electing their own to draw up resolutions, two unnamed African Americans, both fugitive slaves, insisted on addressing the assembly and enlightening the overwhelmingly white audience about the brutal personal assault that the law represented to them. They recounted their escape from slavery to freedom, one giving “expression to his outraged feelings” over the law. While the assembly initially appointed a vigilance committee to secure the safety of “our colored population,” a week later the committee decided that hostility to the fugitive law “was so deep and universal” in Worcester that “a vigilance committee of the whole” seemed unnecessary.13

Worcester’s black population felt far less confident about their security than their white counterparts. According to Isaac Mason, who came to Worcester just before the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law, the “hunting slave fever got so high that our sympathizing friends advised me to leave at once and go to Canada,” which he did for several months. While other Worcester refugees undoubtedly followed Mason’s lead, those who remained dug in their heels to defy the law. With radical white allies such as Martin Stowell, they formed the Worcester Freedom Club as well as a local vigilance committee. Featuring the goddess of liberty, the club’s banner reflected the heartfelt, political sentiments of its members. “Warm Hearts and Fearless Souls— True to the Union and Constitution,” the banner proclaimed on one side; on the reverse, “Freedom National— Slavery Sectional! Liberty! Equality, Fraternity!”14

In the spring of 1854, Worcester’s vigilant resisters entered the fray when they rallied in support of the imprisoned Anthony Burns. Summoned for support by T. W. Higginson, who, with several compatriots, had attempted to free Burns from a Boston prison several days earlier, the Worcester Freedom Club, 500 strong, descended upon Boston. They processed to Court Square, two by two, in a dramatic show of support for the incarcerated Burns. Manifesting Worcester’s radical tradition and activism, the Freedom Club’s appearance “from the rural districts created some excitement among the outsiders, who cheered them with a will.” Although angry opponents destroyed their stunning silk banner, the Worcester delegation nevertheless made a bold and impressive showing. The delegation included many black men from Worcester, and, given their slave backgrounds and leadership positions in the community, William Jankins and Gilbert Walker were probably among them.15

About six months later...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- First Fruits of FREEDOM

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 THE GUNS OF WAR

- Chapter 2 THE PRETTIEST BLUE MENS I HAD EVER SEED

- Chapter 3 THESE ARE THE CHILDREN OF THIS REVOLUTION, THE PROMISING FIRST FRUITS OF THE WAR

- Chapter4 A NEW PROMISE OF FREEDOM AND DIGNITY

- Chapter5 A COMMUNITY WITHIN A COMMUNITY

- Epilogue

- Appendix

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index