- 230 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Highland Scots of North Carolina, 1732-1776

About this book

Using a variety of original sources—official papers, travel documents, diaries, and newspapers—Duane Meyer presents an impressively complete reconstruction of the settlement of the Highlanders in North Carolina. He examines their motives for migration, their life in America, and their curious political allegiance to George III.

This book breaks new ground in discussing the causes of the emigration and the knotty puzzle of the loyalism of the American Scots. Meyer sees not forceable political repatriation but nonpolitical social and economic pressures as the real cause of the Highlander movement to America. He meticulously examines the political allegiance of the highlander settlement in North Carolina.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Highland Scots of North Carolina, 1732-1776 by Duane Meyer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Geschichte & Nordamerikanische Geschichte. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER I

REVOLUTION AND AFTERMATH

Did you ever hear of a loyal Scot

Who was never concern’d in any plot?

Who was never concern’d in any plot?

—from Ancient Ballads of Scotland.1

The Migration of the Scottish Highlanders to North Carolina began in the 1730’s and slowly gained momentum. On the eve of the American Revolution, such large numbers were leaving the Highlands that Samuel Johnson, visiting in North Britain, could speak of an “epidemick desire of wandering which spreads its contagion from valley to valley.”2 The migration brought to America, above all to North Carolina, a large body of settlers known chiefly in American revolutionary history for their devotion to the cause of George III. What can account for the curious transformation of the Highlanders, who in Europe had rallied round the Stuart flag in the Jacobite uprisings known as the Fifteen and the Forty-five, in memory of the years of their occurrence, but who in North Carolina were the loyal supporters of the House of Hanover? Professor Thomas J. Wertenbaker writes: “American historians have been at a loss to explain the loyalty of the Highlanders to the royal cause during the American Revolution. Since many had fought and suffered for the Pretender, and almost all were victims of the recent changes in Scotland for which the government was responsible, one might suppose they would have welcomed an opportunity for revenge.”3 It is only a little less remarkable that a people so imbued with a love of chief and clan and so attached to the braes and glens of the Highlands should have emigrated at all.

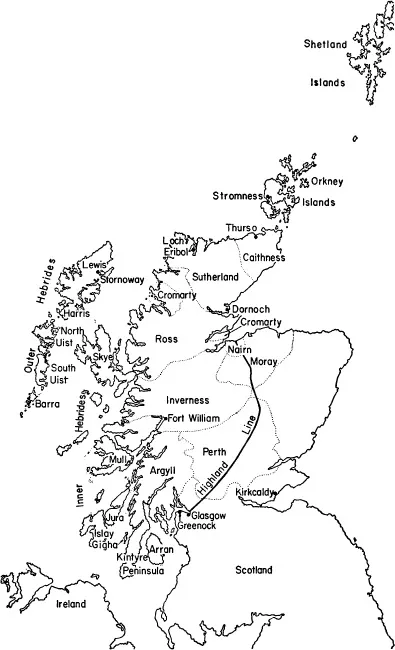

The Highlands of Scotland include those mainland and island areas north and west of a line formed approximately by the foothills of the Grampian Mountains. (See Map I.) This line begins on the north coast midway between the Nairn River and the Findhorn River and runs south-southeast to include in the Highlands the western tips of the present-day shires of Moray, Banff, Aberdeen, and Angus. In the shire of Angus it turns southwest to cross Perthshire and finally ends at the Firth of Clyde in Dumbartonshire after passing just south of Loch Lomond. An ethnic distinction may also be made between the Highlanders and the Lowlanders. The Highlanders were mostly descended from the Irish Gaels while the Lowlanders were the offspring of the Angles of Northumberland.4

In the first half of the eighteenth century, the Highlanders lived in a secluded feudal society under the control of tribal chieftains. A clan warrior received his plot of land from his chief, with whom he usually could claim some blood relationship. In return, the warrior was expected to attend the court of the chief, accept his justice, follow him in war, and pay him rent in kind. In this society methods of agriculture were primitive and farming unproductive. To eighteenth-century Englishmen and Lowlanders, the Highlands seemed a mysterious area populated by people speaking an ancient tongue, perpetuating strange practices, and paying little if any heed to the pronouncements of Parliament.5

Captain Edward Burt, an English engineer traveling through the Highlands in 1730, expressed in his Letters his amazement at the society he discovered. The power of the clan chief over his clansmen was almost unlimited. When Burt was offended by the remarks of a chiefs warriors, the angered patriarch offered to send him “two or three of their Heads” in apology.6 A chief never ventured from his castle without a retinue of gillies (servants), a bard, a piper, and a bladier (spokesman). Women performed much of the agricultural labor, using crude implements constructed largely of wood. The horse collar was not yet used in the Highlands; Burt observed that the people maintained the “barbarous Custom ... of drawing the Harrow by the Horse’s Dock, without any manner of harness whatever.”7 Their agriculture barely produced enough in good years to sustain men and cattle. In bad years large numbers of both perished from starvation.8 Oatmeal, sometimes mixed with a small quantity of milk, at other times with blood from a freshly-bled cow, was the staple food. Butter and eggs were eaten occasionally; meat was consumed rarely.9 After a sojourn in one of the “wretched hovels” of “piled stone and turf” which served as a home, Burt described the interior in this way: “There my Landlady sat, with a Parcel of Children about her, some quite, and others almost naked, by a little Peat Fire, in the Middle of the Hut; and over the Fire-Place was a small Hole in the Roof for a Chimney. The Floor was common Earth, very uneven, and no where Dry, but near the Fire and in the Corners, where no Foot had carried the Muddy Dirt from without Doors.”10

MAP I. THE HIGHLANDS AND ISLANDS OF NORTH BRITAIN

The isolation and tribal character of this poverty-stricken society were destroyed in the Jacobite struggle for the throne of England and Scotland. Some account of the political developments born of this conflict is necessary in order to understand the subsequent emigration of many of the clansmen to America. Members of the House of Stuart (also spelled Stewart and Steuart) had occupied the Scottish throne since the year 1316. In England, the Tudors were the ruling family until the line ran out with the death of the Virgin Queen, Elizabeth I, in 1603. Elizabeth’s cousin and the Scottish King, James VI, was then invited to accept the English crown also. He did so and ruled England as James I. The two nations retained their separate parliaments and councils, but the people were all subjects of the same Stuart monarchs. James and the Stuarts who succeeded him ruled the two nations for a century altogether. James I (VI) ruled from 1603 to 1625, Charles I from 1625 to 1649, Charles II from 1660 to 1685, James II from 1685 to 1688, Mary Stuart and her husband William of Orange, who were joint sovereigns, from 1689 to 1702, and Anne from 1702 to 1714.

The Stuarts, especially those who reigned before 1688, were strong-willed sovereigns, ever upholding the divine right of kings. James I, who was called “the wisest fool in Christendom” by the Duke of Sully, assumed the role of essayist in order to defend this divine right theory.11 On the continent, where every state was subject to invasion, strong rulers and state unity were so necessary for protection that the nobility and middle class were frequently willing to forgo political power. But the English and the Scots felt relatively secure behind their ocean moat. They were not fond of arbitrary rule, and they were particularly jealous of the prerogatives of their respective parliaments. When James VI was five years old, having already served as king for three years, he was taken to visit the Scottish Parliament. Bored with the proceedings, he amused himself by poking his finger through a hole in the tablecloth. So occupied, he inquired where he was. When one of the nobles explained that they were in Parliament, the boy king said, “This Parliament has a hole in it.”12 Perhaps this tale is symbolic of what became a conscious Stuart policy of seeking out the flaws and weaknesses in the parliamentary structure. They objected to parliamentary control over the passage of laws and the levying of taxes. In order to minimize parliamentary criticism of the crown for the assessment of illegal taxes and the issuance of illegal laws, parliaments were called as infrequently as possible.13

Religion was another source of conflict. James I and Charles I both disliked Calvinist policy, which put church control in the hands of presbyteries and a General Assembly. They preferred to have royally appointed bishops directing the church, and their attempts to establish such an episcopal system in Scotland produced bitter Presbyterian opposition. Charles II was secretly Catholic, but James II openly proclaimed his Catholicism. Wily Charles II moved secretly and slowly toward a policy of toleration for Catholics, but blunt and vigorous James II openly attempted to restore Catholicism to its former place in England and Scotland.14

The hostile response of the English and Scottish peoples to these political and religious policies produced some of the most important events in their history. James I and Charles II stirred up a storm of protest by their actions, but they were able to ride out the gale. Charles I and James II were not so fortunate. After a Civil War developed in both Scotland and England, Charles I was made a prisoner of the Puritans and condemned by Puritan justice as “a tyrant, a traitor, murderer, and public enemy of the good people of this nation.”15 He lost his head to the executioner’s axe.

James II retained his handsome head, but not his throne. Blunt, relentless man that he was, he pursued his political and religious policies with such harshness and obstinacy that he soon alienated the members of the English and Scottish Parliaments, the Anglicans, and the Calvinists. In view of his advancing years and the Protestantism of the grown daughters who would succeed him, no attempt was made to depose James II until his bride gave birth to a son in 1688. This brought forth the threat of a Catholic succession and triggered the Glorious Revolution of 1688. A coalition of political leaders advised James to leave the country and invited James’s daughter Mary and her husband William to become the joint monarchs of England and Scotland. Recalling his father’s fate, James fled to France.16

Three important developments occurred near the turn of the century. In 1701, the Act of Settlement provided that the monarch must be Protestant. This was obviously intended to disqualify James II and his son. The Act of Union of 1707 unified the two kingdoms of England and Scotland into one new state known as Great Britain, with a single Parliament located at London. The Presbyterian communion was recognized as the established church in Scotland. When Queen Anne died in 1714, the Elector of Hanover became the English king and took the name George I.17

After 1688, those people in England and Scotland who favored the restoration of James II or, after his death in 1701, the restoration of his son “James III” were known as Jacobites (from Jacobus, the Latin for James). Although they took part in several other uprisings, the main revolutionary efforts of the Jacobites took place in 1715 and 1745 and were, as we have seen, subsequently known as the Fifteen and the Forty-five. It would be naive to assume the Jacobites were motivated solely by their love for James II or “James III” or the House of Stuart. A great tangle of causes lay behind the attempts to depose the Hanoverians. Some opportunists, having failed to secure places of influence or authority in the Hanoverian government, believed they would have more success after a change of dynasty. British Catholics had an obvious reason for supporting the Jacobite cause. The Episcopalians of North Scotland, who disliked the established Presbyterian Church, recalled that the Stuarts had appointed bishops for Scotland, and they longed for a return to that arrangement. During the first half of the eighteenth century, there was always a sizable group of nonjuring Episcopalian clergymen in Scotland who refused to take an oath of loyalty to the House of Hanover. There were also Jacobites who objected to the Act of Union, which they thought subordinated the welfare of Scotland to that of England. They hoped a revolution might reinstate the separate governments. In the Highlands, there was intense hatred for the Campbells and the Duke of Argyle, who were symbols of Hanoverian power in that area. Fired by this enmity, many clans awaited an opportunity to secure revenge for the humiliations they had suffered under the Campbells.18

The Fifteen and the Forty-five were organized in the Highlands of Scotland because there were disgruntled groups in the area and because it was a remote region largely uncontrolled and unpatrolled by the British army. In September, 1715, the Earl of Mar, unhappy at having been removed from his post as Secretary of State by George I, traveled to the Highlands and raised the standard for James Edward, the self-styled “James III.”

Two months later, Mar and his...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- THE HIGHLAND SCOTS OF NORTH CAROLINA 1732–1776

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- PREFACE

- CONTENTS

- MAPS AND FIGURES

- CHAPTER I REVOLUTION AND AFTERMATH

- CHAPTER II THE EXILE THEORY

- CHAPTER III MOTIVES FOR MIGRATION

- CHAPTER IV VOYAGE TO AMERICA

- CHAPTER V SETTLEMENT

- CHAPTER VI LIFE ON THE CAPE FEAR

- CHAPTER VII THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION

- APPENDIX

- NOTES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX