- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Lee and His Army in Confederate History

About this book

Was Robert E. Lee a gifted soldier whose only weaknesses lay in the depth of his loyalty to his troops, affection for his lieutenants, and dedication to the cause of the Confederacy? Or was he an ineffective leader and poor tactician whose reputation was drastically inflated by early biographers and Lost Cause apologists? These divergent characterizations represent the poles between which scholarly and popular opinion on Lee has swung over time. Now, in eight essays, Gary Gallagher offers his own refined thinking on Lee, exploring the relationship between Lee’s operations and Confederate morale, the quality of his generalship, and the question of how best to handle his legacy in light of the many distortions that grew out of Lost Cause historiography.

Using a host of contemporary sources, Gallagher demonstrates the remarkable faith that soldiers and citizens maintained in Lee’s leadership even after his army’s fortunes had begun to erode. Gallagher also engages aspects of the Lee myth with an eye toward how admirers have insisted that their hero’s faults as a general represented exaggerations of his personal virtues. Finally, Gallagher considers whether it is useful — or desirable — to separate legitimate Lost Cause arguments from the transparently false ones relating to slavery and secession.

Using a host of contemporary sources, Gallagher demonstrates the remarkable faith that soldiers and citizens maintained in Lee’s leadership even after his army’s fortunes had begun to erode. Gallagher also engages aspects of the Lee myth with an eye toward how admirers have insisted that their hero’s faults as a general represented exaggerations of his personal virtues. Finally, Gallagher considers whether it is useful — or desirable — to separate legitimate Lost Cause arguments from the transparently false ones relating to slavery and secession.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Lee and His Army in Confederate History by Gary W. Gallagher in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Lee’s Campaigns

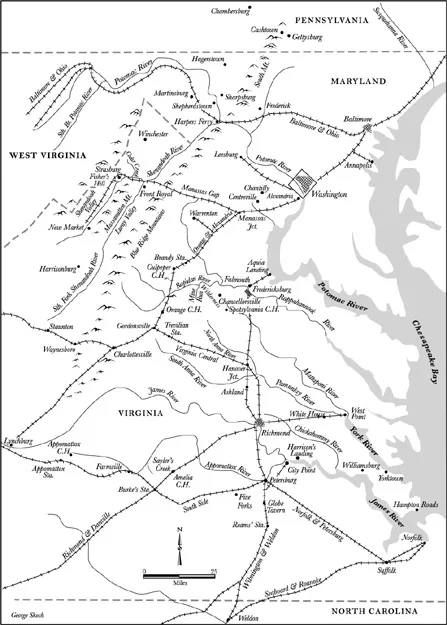

Theater of Operations, April–July 1862

The Net Result of the Campaign Was in Our Favor

Confederate Reaction to the 1862 Maryland Campaign

The roads leading from Sharpsburg to Boteler’s Ford choked under the strain of men, vehicles, and animals during the night of September 18, 1862. Trudging through a sheltering fog that helped mask their movement toward the Potomac River, Confederate soldiers hoped that an enemy who had been quiescent all day would remain so for a few hours longer. A North Carolina chaplain, carried along through the predawn Maryland darkness on this martial tide, left a vivid impression in his diary: “Though troops and wagons have been passing all night, still the roads and fields were full. Ram! Jam! Wagons and ambulances turned over! One man was killed by the overturning of an ambulance.” An artillerist described a more orderly withdrawal, mentioning especially that Robert E. Lee “stood at the ford in Shepherdstown and gave directions to the teamsters and others, showing a wise attention to details which many men in less elevated positions would think beneath their notice.” By eight o’clock on the morning of September 19, all were safely across the Potomac onto Virginia soil.1

Thus ended a fifteen-day campaign in Maryland that represented the final act of a drama begun eighty-five days earlier with Confederate assaults at the battle of Mechanicsville outside Richmond. These twelve momentous weeks had witnessed Lee’s offensive victory over George B. McClellan in the Seven Days and an equally impressive thrashing of John Pope’s Army of Virginia at Second Manassas, which together shifted the strategic focus in the Eastern Theater from Richmond to the Potomac River. Surging across the national frontier into Maryland less than a week after Second Manassas, Lee and his army had hoped to make the strategic reorientation even more striking. Dramatic events in the gaps of South Mountain, at Harpers Ferry, and amid the rolling countryside near Sharpsburg had punctuated Lee’s foray north of the Potomac—and would dominate the thinking of most contemporary observers and later critics who sought to judge what the Army of Northern Virginia had won or lost.

Historians typically have assessed the Maryland campaign from the perspective of its long-term impact, looking back with later events in mind to label it a major turning point that foreshadowed Confederate defeat. Writing in the mid-1950s, Clement Eaton touched on the two factors most often mentioned in this connection: Lincoln’s preliminary proclamation of emancipation and Europe’s decision to back away from recognition of the Confederacy in the autumn of 1862. “The checking of the Confederate invasion at Antietam . . . was disastrous to the cause of Southern independence,” wrote Eaton. “The retreat of Lee not only gave Lincoln a favorable opportunity to issue his Emancipation Proclamation but it also chilled the enthusiasm of the British government to recognize the independence of the Confederacy.” Nearly two decades earlier, Robert Selph Henry had argued similarly in his widely read history of the Confederacy, pointing to Antietam and suggesting that “On the seventeenth day of September in 1862 the decline of the Confederacy began.” Clifford Dowdey, who in the 1950s and 1960s inherited Douglas Southall Freeman’s mantle as the leading popular writer about Lee and his army, added his voice to this chorus, stating bluntly, “Politically, the war ended at Sharpsburg for the Confederacy. That was the last chance the Southern states had really to win independence.”2

More recent historians have continued this interpretive tradition. James M. McPherson’s magisterial history of the conflict reminded readers that the battle of Antietam “frustrated Confederate hopes for British recognition and precipitated the Emancipation Proclamation. The slaughter at Sharpsburg therefore proved to have been one of the war’s great turning points.” In summary comments about Antietam from his overview of the Civil War era, Brooks D. Simpson asserted that “most people, North and South, American and European, interpreted a pitched battle followed by a Confederate withdrawal as a defeat.” The result was diminished chances for European recognition and Lincoln’s opening for the proclamation—a conclusion Charles P. Roland echoed in his insightful survey of the Civil War.3

A decade ago, I summarized the impact of the Maryland campaign on Confederate fortunes in similar terms: “Lee went north and fought, avoided a series of lurking disasters, and found refuge in the end along the southern bank of the Potomac River. But the military events of mid-September 1862 bore bitter political and diplomatic fruit for the Confederacy. The nature of the conflict changed because of Lee’s Maryland campaign.” No longer a contest to restore the status quo ante bellum, “the new war would admit of no easy reconciliation because the stakes had been raised to encompass the entire social fabric of the South. The war after Antietam would demand a decisive resolution on the battlefield, and that the Confederacy could not achieve.”4

The understandable desire to highlight the broad implications of the Maryland campaign has left another important question relatively neglected, namely: How did Confederates at the time react to Lee’s campaign in Maryland? Did the operations of September 1862 engender hope? Did they cause Confederates to lose heart at the thought that their struggle for independence had taken a grim turn downward? Did the campaign provoke a mixed reaction? In short, what impact did Lee’s foray across the Potomac have on his men and on their fellow Confederates?

A survey of military and civilian testimony during the period following Lee’s retreat from Maryland underscores the challenge of assessing the relationship between military events and popular will during the Civil War. Although any such survey is necessarily impressionistic, it is worthwhile searching letters, diaries, and newspaper accounts for patterns of reaction.5 Examined within the context of what people read and heard at the time, and freed from the powerful influence of historical hindsight, Confederate morale assumes a complex character. Rumors and inaccurate reports buffeted citizens long since grown wary of overblown prose in newspapers. Knowing they often lacked sound information, people nonetheless strove to reach satisfying conclusions about what had transpired.

As the autumn weeks went by, they groped toward a rough consensus that may be summed up briefly. The Maryland campaign did not represent a major setback for the Confederacy. Antietam was at worst a bloody stand-off, at best a narrow tactical success for Confederates who beat back heavy Union assaults and then held the field for another day. “Stonewall” Jackson’s capture of 12,000 Union soldiers and immense matériel at Harpers Ferry and A. P. Hill’s stinging repulse of Union forces at Shepherdstown on September 20 marked unequivocal high points of the campaign. McClellan’s inaction throughout late September and October demonstrated how badly his army had been damaged, and Lincoln’s emancipation proclamation betrayed Republican desperation and promised to divide northern society. Reconciled to the fact that the war would not end anytime soon, most Confederates looked to the future with a cautious expectation of success.6

In one important respect, the Maryland campaign served as the coda to a different kind of watershed than most historians have described. Lee and his army emerged from Maryland as a major rallying point for the Confederacy. Their operations between July and September began the process that, within another eight months, would make them the focus of Confederate national sentiment. Starting in the autumn of 1862, white southerners increasingly contrasted Lee’s and Jackson’s successes in the Eastern Theater with repeated failures in the Western Theater, concluding that prospects for victory would rest largely on the shoulders of Lee and his lieutenants and on the bayonets of their soldiers. Better attuned to Confederate sentiment than many later historians would be, Edward A. Pollard of the Richmond Examiner touched on this point in his wartime history of the Confederacy. “The army which rested again in Virginia had made a history that will flash down the tide of time a lustre of glory,” wrote Pollard in 1863 of the aftermath of the Maryland campaign. “It had done an amount of marching and fighting that appears almost incredible, even to those minds familiar with the records of great military exertions.” The “remarkable campaign . . . extending from the banks of the James river to those of the Potomac,” concluded Pollard, “impressed the world with wonder and admiration.”7

Newspapers supplied most Confederates outside Lee’s army with their initial impressions about the Maryland campaign. As is always the case, such accounts must be read with the understanding that editors often tried to shape public opinion as well as inform readers about what had transpired. During the initial phase of reporting, editors typically took the stance that Sharpsburg ranked among the bitterest of engagements and, though perhaps not a clear southern victory, reflected well on Confederate prowess. Six days after the battle, for example, Charleston’s Mercury admitted that accounts of fighting at Sharpsburg were “meagre and somewhat contradictory, but all agree in representing it to have been the most bloody and desperately contested engagement of the war.” The outnumbered Confederate army had “again illustrated its valor and invincibility by successfully repelling the repeated onsets of the enemy.” The Charleston Daily Courier noted that “All accounts agree in representing that the fight of Wednesday was closely contested,” adding that a reliable witness quoted General Lee as saying he “looked upon the struggle of that day as favorable to our arms.” Richmond’s Dispatch, which had the largest circulation among the capital’s newspapers, took a bit more optimistic view: “[I]t is evident that we were victorious on Wednesday. We acted on the defensive. The enemy tried a whole day to drive us from our position. He utterly failed. We held our position, and slept on the ground, ready to renew the contest the next day.” Even less restrained was the Richmond Enquirer, which breathlessly announced that “the battle resulted in one of the most complete victories that has yet immortalized Confederate arms.”8

The capture of Harpers Ferry received wide coverage and almost universal praise, 9 as did the battle of Shepherdstown. Little remembered now, the latter loomed much larger in September 1862 and satisfied Confederate yearnings for offensive victories. In reporting on Shepherdstown, the Richmond Weekly Dispatch described how a Union column had crossed at Boteler’s Ford in pursuit of the Army of Northern Virginia, only to be driven back by A. P. Hill’s outnumbered division: “Our forces poured the grape and canister into them as they crossed the Potomac, and the slaughter was terrible.” Fleeing Federals fell in such profusion that the “river was black with them.” The Charleston Daily Courier termed the fight “a severe engagement . . . in which the Yankees were almost annihilated. They were driven into the river, shot down by hundreds, and those who survived taken prisoner.” Peter W. Alexander, among the best of the Confederate military correspondents, reported “additional particulars . . . of the affair at Shepherdstown” for the Savannah Republican on September 23. Quoting a Federal surgeon, Alexander stated that “about 2,000 Federal infantry attempted to cross after us, and out of that number only ninety lived to return. Such as were not killed and drowned, were captured.”10

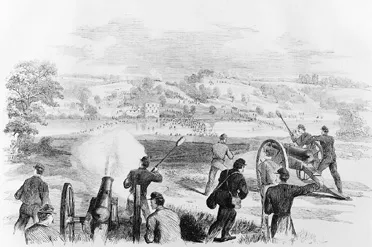

Artillery covering the Union retreat at the battle of Shepherdstown on September 20, 1862. Confederates applauded this engagement as a bloody debacle for George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac . (Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, October 25, 1862)

Lee’s decision to seek shelter south of the Potomac after Sharpsburg provoked far more disagreement among editors than the apparently uncomplicated Confederate successes at Harpers Ferry and Shepherdstown. The Charleston Mercury somewhat sarcastically called the crossing at Boteler’s Ford a “movement which, to the un-military eye, with no more subtle guide than the map, would certainly resemble a retreat.” Richmond’s Dispatch disagreed, emphasizing “the wearied and almost starving condition of our men,” and rationalizing the withdrawal as “made necessary not by any reverse in battle, but by the stern exigency of the absence of commissary supplies.” The Enquirer reported that “McClellan’s army was too badly used up on Wednesday . . . to perform any rapid movement for strategic effect.” As a consequence, continued this pro-Davis administration paper, the “movement of a portion of our forces to the South side was purely a matter of precaution, to provide against possible contingencies.” Seldom has more nebulous language been used to place a positive gloss on an army’s retreat (the degree to which the Enquirer achieved its goal cannot now be determined).11

Newspapers also argued about Lee’s goals in entering Maryland. The Enquirer claimed that “our distinguished General projected the movement into Maryland as a cover to his march against Harper’s Ferry, and for the purpose of drawing McClellan out of Washington.” Having established a standard by which to evaluate Lee’s operations, the paper added: “He has entirely succeeded. Harper’s Ferry has fallen, and McClellan enticed sixty-five miles from Washington, has been defeated.” With an eye toward those who questioned the retreat on September 18, the Enquirer concluded that “Such glorious triumphs should teach our people the utmost reliance on General Lee, and make them easy even when they do not understand his movements.”12

In Charleston, the Mercury would have none of this, noting dismissively that that the Enquirer “professes, in a soothing article, to believe that Lee contemplated only the capture of Harper’s Ferry in his advance into Maryland.” The Mercury suspected more had been intended, and less accomplished. For one prominent Confederate, at least, the Enquirer’s position carried the day against the Mercury. According to the Southern Confederacy of Atlanta, Vice President Alexander H. Stephens considered the capture of Harpers Ferry to have been “Lee’s principal object in going into Maryland,. . .[and] one of the most brilliant achievements of the war.” The battle of Sharpsburg was “only an incident to the main object, in which our forces were victorious, though the victory was dearly bought.”13

All of the newspapers discussed the problem of straggling among Lee’s soldiers. “Candor compels me to say,” admitted one correspondent from the field, “that the straggling and desertion from our army far surpasses anything I had ever supposed possible.” Although editors strongly deplored the absence of stragglers at Sharpsburg, where comrades in the laggards’ units fought bravely ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Lee & His Army in Confederate History

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Essay Credits

- Part One Lee’ Campaigns

- Part Two Lee as a Confederate General

- Part Three Lee & His Army in the Lost Cause

- Index