eBook - ePub

From Catharine Beecher to Martha Stewart

A Cultural History of Domestic Advice

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Today’s domestic-advice writers — women such as Martha Stewart, Cheryl Mendelson, and B. Smith — are part of a long tradition, notes Sarah Leavitt. Their success rests on a legacy of literature that has focused on the home as an expression of ideals. Here, Leavitt crafts a fascinating genealogy of domestic advice, based on her readings of hundreds of manuals spanning 150 years of history.

Over the years, domestic advisors have educated women about everything from modernism and morality to sanitation and design. Their writings helped create the idealized vision of home held by so many Americans, Leavitt says. Investigating cultural themes in domestic advice written since the mid-nineteenth century, she demonstrates that these works, which found meaning in kitchen counters, parlor rugs, and bric-a-brac, have held the interest of readers despite vast changes in women’s roles and opportunities.

Domestic-advice manuals have always been the stuff of fantasy, argues Leavitt, demonstrating cultural ideals rather than cultural realities. But these rich sources reveal how women understood the connection between their homes and the larger world. At its most fundamental level, the true domestic fantasy was that women held the power to reform their society through first reforming their homes.

Over the years, domestic advisors have educated women about everything from modernism and morality to sanitation and design. Their writings helped create the idealized vision of home held by so many Americans, Leavitt says. Investigating cultural themes in domestic advice written since the mid-nineteenth century, she demonstrates that these works, which found meaning in kitchen counters, parlor rugs, and bric-a-brac, have held the interest of readers despite vast changes in women’s roles and opportunities.

Domestic-advice manuals have always been the stuff of fantasy, argues Leavitt, demonstrating cultural ideals rather than cultural realities. But these rich sources reveal how women understood the connection between their homes and the larger world. At its most fundamental level, the true domestic fantasy was that women held the power to reform their society through first reforming their homes.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access From Catharine Beecher to Martha Stewart by Sarah A. Leavitt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1: Going to Housekeeping: Creating a Frugal & Honest Home

“Why,” says Helen, “I have thought of the éclat of the engagement, and then the buying lots of things and having them made up in the very latest style, and the cards, the cake, the presents, and the bridesmaids. I shall have an elegant veil and a white silk, and be married in church, and have three Saratoga trunks, and a wedding trip, and—well, that’s as far as I’ve gone. I suppose after that one boards at a hotel, or has to go to housekeeping, and I’m afraid it would be dreadfully humdrum. But no more so than flirting with one and another year after year, and seeing all the girls married off.”

“For my part,” said Miriam, “I have not looked at all this style and preparation that Helen describes, because I know I cannot afford it. But I have thought I should like a little home all to myself, and I would keep it as nice as I could, and I would try to help my husband on in the world, and we should have things finer only as we could really afford it. And I should want my home to be very happy, so that all who belonged in it felt that it was the best place in all the world. I should want to gather up all the good that I could everywhere, and bring it into my home, as the bee brings all its spoils to the hive.”

“And I,” said Hester, “want to make myself a scholar, and I shall marry a scholar, and we shall be happy in learning, and in increasing knowledge. And he shall be my helper, and I shall help him, and so together we shall climb to the top of the tree.”

Vanity, love, ambition. These were the three Graces, which, incarnated in my nieces, sat on my piazza. I said to them: “Let me talk to you seriously upon the subject of a Home.”

—Julia McNair Wright, The Complete Home

In Julia McNair Wright’s 1879 domestic-advice manual, The Complete Home, she took the voice of “Aunt Sophronia” and discussed home-making with her three nieces, Helen, Miriam, and Hester. Each niece represented a certain subset of American women. Miriam, as the niece who wanted a comfortable, simple home where everyone would feel welcome, represented the ideal of most domestic advisors in the nineteenth century: the domestic fantasy.

Miriam, the ideal housewife, provides a window into the dreams of household advisors in the late nineteenth century. Her faulty cousins Hester and Helen are useful counterpoints because they help illustrate the pitfalls that domestic advisors worried about and continue to worry about in the twenty-first century. Hester is too concerned with her career and intellect and not concerned enough with her house and family. In contrast, Helen is obsessed with the frills and fanciness she imagines will accompany romance and conquest of a husband, but has not stopped to think about her home and her role in keeping that home in the future. Only Miriam, the ideal, understands the true purpose of her life as a middle-class white American woman. She knows that she can only have what she can afford, and she wants nothing more than to see her house as the embodiment of love.

How did domestic advisors such as Julia McNair Wright try to convince their readers to act and live more like Miriam than Hester or Helen? Through a long and steady campaign over more than a century, household advisors have argued that women should spend more time in their homes, conform to certain ideals, and spend less time in the wider world. They have consistently argued that women pay attention to their finances and live within their means, not trying to outclass the neighbors through a false show of wealth. Most importantly, they have made the point that a woman’s virtue and worth can be found in the way she furnishes her home. Advisors saw instructions on the arrangement of the furniture and the types of wood used in the parlor not only as aesthetic concerns, but as symbols of honesty, faith, and good judgment.

Domestic advice manuals originated in the 1830s with the Victorian era and its emphasis on home and family. Throughout the nineteenth century, books, newspapers, magazines, advertisements, and other public forums strengthened the connection between women and the home. Domestic advisors, whether single, widowed, or married, tended to be white, middle-class women who had some personal experience with homemaking. They relied upon an audience of the newly literate, white middle class, a population that continued to build in America after 1800.1 In 1840, 38 percent of white Americans of school age received some kind of formal education. By the mid-nineteenth century, most white women could read and write.2 And women were consumers, too, making women’s novels into the best sellers of the 1850s.3 Women readers voraciously demanded constant reprints of sentimental favorites, such as Charlotte Temple, throughout the nineteenth century.4 The domestic-advice manuals took advantage of this new audience.

Lydia Maria Child wrote the first domestic-advice manual for American housewives. Her American Frugal Housewife (1828) was already in its twelfth edition by 1832. Lydia Maria Child was a popular fiction writer who wrote poems, short stories, and the lyrics to a still-famous song called “Grandma’s Thanksgiving.” Born in Medford, Massachusetts, in 1802, Child was educated at Miss Swan’s seminary in Watertown and worked as a schoolmistress until her marriage to David Lee Child in 1828. She edited the Juvenile Miscellany, a children’s monthly periodical, for several years while establishing herself as a writer and an abolitionist in Boston. She became strongly identified with the antislavery cause in New England and edited The Anti-Slavery Standard with her husband during the 1840s. One of her more famous projects was editing the memoir of Harriet Jacobs, which later became Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861).

Child wrote about many different subjects. She wrote novels, including Hobomok (1824) and The Quadroons (1842). She wrote histories, about the Pequot Indians of New England and about the evils of slavery. Her domestic advice manual, which she wrote relatively early in her career, gave her some degree of notoriety, but domestic advice was only a part of her long writing career in which the emphasis was always on moral integrity.

Child’s American Frugal Housewife was filled with admonitions about indolence, frivolity, and waste. She focused on the needs of the homemaker, but also addressed issues not directly related to the home, such as travel. Her severe attitude against spending money on useless extravagance resulted in stories that addressed themes such as a family who could not afford a vacation but took one anyway. “To make a long story short,” she wrote, “the farmer and his wife concluded to go to Quebec, just to show they had a right to put themselves to inconvenience, if they pleased. They went; spent all their money; had a watch stolen from them in the steamboat; were dreadfully sea-sick off Point Judith; came home tired, and dusty; found the baby sick, because Sally had stood at the door with it, one chilly, damp morning, while she was feeding the chickens.”5 The story went on, concluding that the farmer and his wife would have been better off remaining at home, saving their money, and not leaving their children with strangers. Frugal Housewife is filled with such stories of people who squandered away their earnings instead of using every moment and every cent to further the cause of the morally pure home.

Many women in the mid-nineteenth century took up Lydia Maria Child’s idea to address women’s concerns through household advice. Indeed, some of the authors, including Child, Catharine Beecher, Helen Hunt Jackson, and Sarah Josepha Hale were among the most influential women writers of the nineteenth century.6 Others also had successful writing careers, from Harriet Spofford, a popular fiction writer, to Julia McNair Wright, a Christian reformer. These women all chose the middle-class female’s connection to the home as one of the most important subjects, no matter what their other interests. They wrote fiction and political treatises, travelogues and poetry. They led campaigns for women’s education, for abolition, and for temperance. And they also wrote domestic advice.

Often, women used fiction and writing about domesticity as ways to deliver political messages. Helen Hunt Jackson was an outspoken critic of governmental policy toward Native Americans. She wrote scathing reports, such as “A Century of Dishonour; a Sketch of the United States Government’s Dealings with Some Indian Tribes,” and spent time in Colorado and California observing race relations in the West. But despite her desire to communicate her message at levels as high as the United States Congress, Jackson also believed that ordinary women could be an important audience for her ideas. Her Bits of Talk about Home Matters (1879) merged the theme of personal responsibility with a household-management text aimed at middle-class women.7 Jackson also used fiction successfully; her incredibly popular novel Ramona (1884) openly addressed relationships between the Mexicans, Native Americans, and Anglos in California.

Fiction for women and domestic-advice manuals shared many ideals of “moral education.” Sentimental novels throughout the nineteenth century, such as Hope Leslie (1827) by Catharine Maria Sedgwick, The Wide, Wide World (1851) by Susan Warner, and The Lamplighter (1854) by Maria Susanna Cummins, explored the lives of young girls in the context of religious growth. The heroines of these novels experienced life changes, such as losing their family and home, and turned them into life lessons. Writers of sentimental fiction explored moral integrity through broad, often epic, plot lines involving dozens of characters. The popularity of fiction for women gave domestic advisors an audience that would understand their work.

Many of the characters in sentimental novels served as symbols for religious teachings. Domestic-advice manuals would pick up on this convention, but use furniture and carpets in place of characters as symbolic teachers. In The Lamplighter, for example, Cummins used a character named Emily to represent religious purity for Gerty, the heroine. In one scene, Gerty repressed her natural instinct to cry out and composed herself “at the sight of Emily, who, kneeling by the sofa, with clasped hands … looked the very impersonation of purity and prayer.”8 Indeed, women writing about the home personified furniture with qualities such as “honesty” and “purity” just as novelists characterized people as archetypal examples of virtue.

The close connection with novels gave domestic-advice manuals a familiar literary form. This format probably helped women readers to understand the emerging genre and to know what to expect. The dozens of domestic-advice manuals published in the decades after 1830 followed a clear pattern, established to guide women readers through the house. An extensive table of contents emulated the novel’s list of chapter titles. Some authors even used fictional characters. Julia McNair Wright wrote The Complete Home from the standpoint of musings and conversations of the fictional Aunt Sophronia, with occasional commentary from Cousin Ann and Mary. These fictional characters helped readers understand the domestic-advice manual.

Marion Harland in Common Sense in the Household was one of the most intimate writers. The first chapter of her 1871 volume was called “Familiar Talk”:

I wish it were in my power to bring you, the prospective owner of this volume, in person, as I do in spirit, to my side on this winter evening, when the bairnies are “folded like the flocks”; the orders for breakfast committed to the keeping of Bridget, or Gretchen, or Chloe, or the plans for the morrow definitely laid in the brain in that ever-busy, but most independent of women, the housekeeper who “does her own work.” … I should not deserve to be your confidant, did I not know how often, heart-weary with discouragement … you would tell me what a dreary problem this “woman’s work that is never done” is to your fainting soul.9

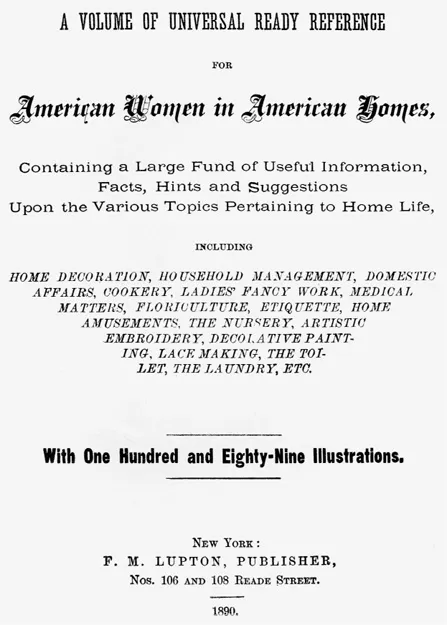

Many late-nineteenth-century domestic advice manuals offered a spectacularly wide range of information for women. This volume, for example, promised “a large fund of useful information” about domestic subjects ranging from home decoration to floriculture. The book, published in 1890, claimed to “include every subject in which woman is interested, wherein information of a practical nature can be imparted through printed instructions.” (The American Domestic Cyclopaedia, title page; courtesy The Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection)

Harland’s intimacy with her reader here emulated the sentimental novels in which authors routinely placed the reader in the position of the heroine.10

Marion Harland created the intimate style she used with her readers over several decades of writing. Born in Virginia in 1830, Mary Virginia Hawes Terhune (Marion Harland was a pen name) began writing stories as a teenager. Her many books included fictional stories, such as her first work Alone (1855), cookbooks, and even an autobiography in which she discussed her conflicted feelings about slavery. Many members of the Terhune family became influential writers. Daughters Christine Terhune Herrick and Virginia Terhune Van de Water also wrote domestic advice manuals, First Aid to the Young Housekeeper (1900) and From Kitchen to Garrett (1912). Harland’s best-selling Common Sense in the Household was so popular that she soon revised it, commenting in the 1880 introduction that the book had to be completely reprinted. “Through much and constant use—nearly 100,000 copies having been printed from them—the stereotype plates have become so worn that the impressions are faint and sometimes illegible.”11 The popularity of Marion Harland’s work in the late nineteenth century demonstrated the power that domestic-advice manuals were beginning to have in capturing an eager audience of American women.

Besides fiction, the cookbook was another popular genre of reading material for American women in the early nineteenth century. Although early cookbooks loo...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- From Catharine Beecher to Martha Stewart: A Cultural History of Domestic Advice

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Going to Housekeeping: Creating a Frugal & Honest Home

- Chapter 2: The Rise of the Domiologist: Science in the Home

- Chapter 3: Americanization, Model Homes, and Lace Curtains

- Chapter 4: Modernism: No Junk! Is the Cry of the New Interior

- Chapter 5: Color is Running Riot: Character, Color, & Children

- Chapter 6: Our Own North American Indians: Romancing the Past

- Chapter 7: Togetherness & The Open-Space Plan

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index