eBook - ePub

To Save the Land and People

A History of Opposition to Surface Coal Mining in Appalachia

- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

To Save the Land and People

A History of Opposition to Surface Coal Mining in Appalachia

About this book

Surface coal mining has had a dramatic impact on the Appalachian economy and ecology since World War II, exacerbating the region’s chronic unemployment and destroying much of its natural environment. Here, Chad Montrie examines the twentieth-century movement to outlaw surface mining in Appalachia, tracing popular opposition to the industry from its inception through the growth of a militant movement that engaged in acts of civil disobedience and industrial sabotage. Both comprehensive and comparative, To Save the Land and People chronicles the story of surface mining opposition in the whole region, from Pennsylvania to Alabama.

Though many accounts of environmental activism focus on middle-class suburbanites and emphasize national events, the campaign to abolish strip mining was primarily a movement of farmers and working people, originating at the local and state levels. Its history underscores the significant role of common people and grassroots efforts in the American environmental movement. This book also contributes to a long-running debate about American values by revealing how veneration for small, private properties has shaped the political consciousness of strip mining opponents.

Though many accounts of environmental activism focus on middle-class suburbanites and emphasize national events, the campaign to abolish strip mining was primarily a movement of farmers and working people, originating at the local and state levels. Its history underscores the significant role of common people and grassroots efforts in the American environmental movement. This book also contributes to a long-running debate about American values by revealing how veneration for small, private properties has shaped the political consciousness of strip mining opponents.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access To Save the Land and People by Chad Montrie in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Environmental Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Making, Taking, and Stripping the Land

The Appalachian Mountains derive their name from the Apalachee, a group of North American aboriginal people who once inhabited present-day northern Florida and southern Georgia. European explorers of the sixteenth century first applied an altered name of the tribe to the highlands as they made their way across the southeastern part of what is now the United States. Only well after the Civil War did “Appalachia” refer to more than a physiographic mountain system. Those who studied and wrote about the region in the antebellum period thought of it solely as a place characterized by a particular topography and lithology. This understanding of Appalachia has been complicated somewhat by late-nineteenth-and twentieth-century efforts to define the area culturally and economically. But contemporary geographers and geologists alike continue to think about the region in terms of its notable surface features and rocks.1

Viewed as the eroded remnants of an ancient mountain system, Appalachia stretches from Newfoundland, in easternmost Canada, to northern Alabama, in the southeastern United States, a distance of nearly 2,000 miles. Yet the Appalachians are not a single range of mountains. They can be divided up into northern and southern segments, roughly corresponding to the glaciated and unglaciated sections, meeting at the Hudson and Mohawk Valleys in present-day New York. Furthermore, while the northern segment of the mountain system is undifferentiated, the southern section can be broken up into four belts or provinces, identifiable mountain groups running parallel to the whole chain. Each of these provinces—the Appalachian Plateau, Valley and Ridge Province, Blue Ridge Province, and the Piedmont Fold and Thrust Belt—have distinct geological histories and appearances all their own.2

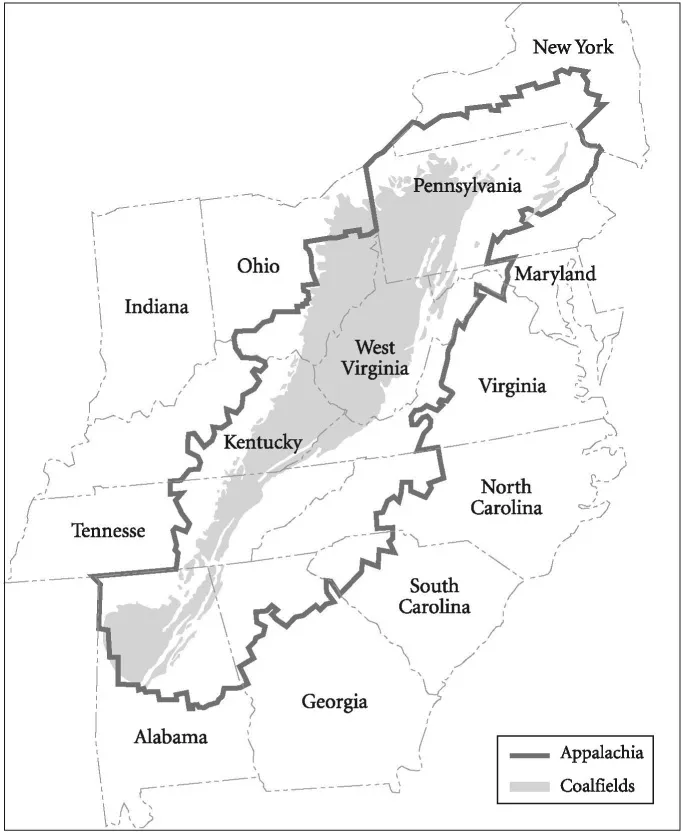

MAP l. Strip coalfields of Appalachia

Farthest northwest in the southern segment is the Appalachian Plateau, extending from northern Alabama to eastern New York. Despite the name, only parts of this province are true plateau, an elevated and level expanse of land. Most of it is dissected by deep valleys and some of the area is mountainous. The province includes the Catskill Mountains in southeastern New York, the Pocono Plateau of northeastern Pennsylvania, the Allegheny Mountains from north-central Pennsylvania to southeastern Virginia, southeastern Kentucky, and southern Tennessee, as well as the Cumberland Plateau from central Tennessee to northern Alabama. The rock layers in these areas are primarily flat-lying or nearly flat-lying and sedimentary in origin, formed by the cementation of pieces of preexisting rocks or precipitated from water. They date from the late-Proterozoic to Paleozoic Eras, and much of the bituminous coal mined in Appalachia comes from the province’s strata of the Pennsylvanian Period (ca. 320-286 million years ago).3

The second belt, moving southeastward, is the Valley and Ridge Province. This belt follows the length of the Appalachian Plateau and is characterized by narrow ridges running parallel to one another for tens or hundreds of miles. Between the ridges are parallel valleys, some of which are quite broad. The southeastern side of the belt, in fact, is nearly a single valley, varying between 2 and 40 miles across and running from New York to Alabama. Like the Appalachian Plateau, most of the rocks in these ridges and valleys are a varied succession of sedimentary rocks dating from the late-Proterozoic Era through the Paleozoic Era, including shale, limestone, and sandstone. These rocks do not lie flat, however, because extensive folding and faulting have taken place in the province. Yet, again like the strata of the Appalachian Plateau, parts of the Valley and Ridge belt are coal-bearing. The most important of these areas is in northeastern Pennsylvania, where four major coalfields make up the Anthracite Region.4

The third belt in the southern segment of the Appalachian Mountain system is the Blue Ridge Province. Shorter and narrower than the other three, it stretches from southern Pennsylvania to northern Georgia in a thin strip that widens somewhat in southwestern Virginia. To the north the province consists of a single massive ridge, 10 to 20 miles across, which then diverges into two principle ridges at Roanoke. The Unaka or Great Smoky Mountains of eastern Tennessee are the higher, massive northwestern ridge and the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia and North Carolina are the southeastern ridge. Adjacent to these mountains is the Piedmont Fold and Thrust Belt, the fourth province, extending from New England to the middle of Alabama, with the Fall Line as its southeastern edge. Both provinces have sedimentary and metamorphic rocks, dating back to the Cambrian Period and earlier, but neither has any significant coal seams.5

The formation of coal in the Appalachian Plateau and Valley and Ridge provinces during the Pennsylvanian Period, and elsewhere at different points in time, is reasonably well understood by geologists. They disagree, however, about the process of deposition. Coal forms when fossil plants are carbonized under high temperatures and pressures, removing various gaseous and liquid compounds and leaving carbon films. Put simply, coal is condensed and altered forms of organic matter, such as spores, ferns, conifers, and ancient scale trees. The amount of heat and pressure this organic matter is subjected to over time determines the rank of the coal, that is whether it remains as peat or ultimately becomes lignite, bituminous coal, or anthracite coal. Peat occurs at the earth’s surface and consists of plant debris that has not been carbonized. Lignite is a soft brown coal in which carbonization has begun to take place but has not advanced very far. Bituminous coal is black, hard, and bright and contains more carbon than lignite but retains some volatile matter. This low-grade coal can form under the weight of a thick overlying sedimentary pile. Anthracite coal is even blacker, more dense, and shinier, with a higher carbon content and little volatile matter. The formation of this high-grade coal requires additional heat and pressure, such as that found inboard of tectonically active margins of continents. Coals of each rank are found in beds or seams—sometimes in a horizontal position as when they were deposited—but of varying thickness and distance from the surface.

In the 1930s, J. Marvin Weller noted that coal beds were part of a sequence of rocks, typically wedged between a grouping of sandstone, sandy shales, and underclay and another grouping of marine limestones and shales, and this sequence was repeated in the stratigraphic column. He explained these cycles of sedimentary rock, or cyclothems, as the result of repeated uplift, erosion, subsidence, and inundation by a shallow sea. Coal was formed during the periods of subsidence, which were marked by increased rainfall, the growth of lush vegetation, and the accumulation of peat in extensive swamps. But Weller’s tectonic hypothesis, as it was called, required an unreasonably large number of uplifts and downwarps, and this problem prompted a search for another explanation. In 1936, Harold R. Wanless and Francis P. Shepard argued that global fluctuation in sea levels due to climate-induced waxing and waning of glaciers (glacio-eustasy) produced the “rhythmic alternations of sediment” during the Pennsylvanian Period, as well as in the Early Permian. Coal beds were formed across the North American continent, they maintained, when increased humidity associated with melting glaciers and a warmer climate created conditions favorable for the growth of vegetation and swamps developed in the lowlands. A subsequent rise in sea level facilitated carbonization of swamp plants (by creating a low-oxygen environment) and resulted in the formation of shales and limestones. In time, vegetation decreased in the uplands and sands poured out on the piedmont, bringing a sedimentary cycle to a close.6

Some geologists have now settled on a blend of the two earlier positions to explain the origins of coal-bearing cyclothems across the ancestral North American continent. Tectonically induced changes in sea level were predominant in the Central Appalachian Basin, they contend, and these were concurrent with climate-induced variations, which had a greater impact on the Illinois and Kansas Basins farther west. Past proponents of the contending hypotheses had simply been focusing on two end-member processes that occurred at the same time. According to George Klein and Jennifer Kupperman, mountain building along the eastern margin of the North American continent caused rapid, short-term tectonic changes and cyclic variation in sea level. With each flexural event, Klein explains in an article with Debra Willard, basins were underfilled and marine waters transgressed on the land. But mountains eroded and shed sediment, which filled the basins to sea level. This produced the swampy conditions conducive to the creation of peat, which later became coal. A cycle then ended with more uplift and the retreat of oceans.7

Whatever their origins—and that is still a matter of some debate—the sedimentary cycles responsible for coal deposition in Appalachia ceased by the start of the Mesozoic Era (ca. 245 million years ago).8 Yet the Appalachian mountain system continued to undergo important geological changes. During the Permian and Triassic Periods some of the horizontal beds of rock laid down as part of sedimentary cycles were subjected to folding and compression. In northeastern Pennsylvania this pressure and the accompanying heat metamorphosed the coal into anthracite. Pressure drove off gases and impurities, increased the proportion of carbon, and left an organic compound with a high heat output and low ash content. On the eastern edge of the Appalachian Plateau, coal was similarly affected by folding and compression, but it was not subjected to enough pressure to transform it into anthracite. In areas further to the west, beyond the deformation zone, the coal retained much of its volatile gases and sulfur.9

Taking the Land: Dispossession of Early Inhabitants and Capitalist “Development”

When Europeans first stumbled upon North America in the fifteenth century there were as many as fifteen indigenous tribes living in the southern mountain region. By the eighteenth century, however, many of the tribes had been decimated by diseases, a result of the exchange of European pathogens to which they had no immunities. For those tribes that did persist, continued epidemics and other factors weakened the ability of the indigenous people to resist the encroachment of white settlers, and the Europeans took their lands. The Cherokee alone lost 40 percent of their territory by the end of the Revolutionary War, and they ceded an additional 3 million acres between 1800 and 1819. Through a campaign of so-called Indian wars, U.S. soldiers displaced (either exterminated or forced to reservations) nearly all the bands of native people between the Great Lakes and the Gulf of Mexico, opening up the northwest and southwest territories for white settlement.10

Yet, as Wilma Dunaway explains, not all white settlers fared equally well in Appalachia during its frontier years. Federal laws designed to protect the rights and promote the interests of aspiring homesteaders were not implemented until the middle of the nineteenth century, and these laws were designed to regulate settlement in the Midwest. During the preceding decades northeastern merchant capitalists, land companies, and southern planters managed to expropriate most of the Appalachian region’s total acreage. By the mid-1700s tidewater planters and British Court favorites had acquired much of southwest Virginia, present-day West Virginia, and western Maryland. In western North Carolina, planters and two land companies monopolized a good portion of the northern sector. By the end of the eighteenth century, probably three-quarters or more of eastern Kentucky’s frontier lands were held by absentee speculators. And in Tennessee, merchant capitalists, land companies, and distant planters amassed more than two-thirds of the territory’s mountain region. Having engrossed the land with the purpose of making a profit, these speculators charged high prices for their acreage and, as a result, at least two-fifths of settler households were without land in the antebellum period.11

Due to inequitable patterns of land ownership, eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Appalachia did not initially exemplify Thomas Jefferson’s vision of a democratic, egalitarian society based on independent, small freeholders. A speculative market in land gave rise to social stratification, which characterized rural communities of the region just as it did industrial cities of the Northeast and Midwest. Yet even as the engrossment of land imperiled many mountain settlers’ dreams of a “competency,” most of them continued to believe in and strive for the Jeffersonian ideal. Their qualified success in achieving a life of propertied independence—often by squatting on land owned by others—is evidenced by the fact that generally self-sufficient family farms did eventually become the backbone of the Appalachian economy. By 1880, Appalachia contained a greater concentration of noncommercial family farms than any other part of the nation.12

Through the first half of the nineteenth century, however, the inhabitants of the southern mountains were still not “Appalachians.” The creation of Appalachia as a coherent region inhabited by a homogenous population with a uniform culture, as Henry Shapiro has put it, was a post-Civil War phenomenon. In the antebellum period, travel literature presented mountain people as no different from other Americans, or at least as no different from other southerners. A few accounts even incorporated an awareness of the ways in which the southern highlands were internally differentiated, recognizing the difficulty of making generalizations about the mountains and its inhabitants. But the 1870s saw the rise of local color writing, which focused on the supposed peculiarities of non-urban people and places. With it came the literary, social, and economic transformation of Appalachia. Though the local color genre was not limited to descriptions of the southern highlands, it was there that it had the most significant and lasting impact.13

One of the first writers to assert the “otherness” of Appalachia was Will Wallace Harney, who published “A Strange Land and Peculiar People” in Lippincott’s Magazine in 1873. Similar essays by other local colorists followed. In more than two hundred travel accounts and short stories of the local color variety published between the early 1870s and 1890, southern mountaineers were presented as backward and isolated from the mainstream of American life. By the turn of the century, various individuals were citing this regression as the basis for a mission of uplift. In an address entitled “Our Contemporary Ancestors in the Southern Mountains” (1899), Berea College president William G. Frost called attention to the special needs of “mountain whites” and, like many others, compared “Appalachian America” to Revolutionary America. Both had the same population, he said, the former having progressed little beyond the latter’s level of civilization. For Frost and other observers, as Allen Batteau notes, it was not so much strangeness as familiarity that made Appalachia interesting and worthy to America. The roots of an American cultural identity could be found in the people of the southern mountains: to be Appalachian was to be quintessentially American. Yet the perception of mountaineers as an isolated people of another time also required ameliorative programs of action.14

The social construction of an Appalachian people spoke to the need for a rising, urban-industrial middle class to see southern mountain people as a repository of an increasingly threatened republican inheritance. Yet to missionaries, entrepreneurs, and others shaped by late-nineteenth-century urban-industrial transformation, southern highlanders also badly needed modernization. To missionaries, the mountaineers whom they romanticized as “contemporary ancestors” needed social uplift, the betterment that would bring their values and mores up to date. They were deserving of help because of the independence and individualism fostered by geographic isolation, but their feuding, moonshining, and parochialism had to be addressed if Appalachia was not to remain a pocket of backwardness. “[W]here the local colorists had been content to see mountain life as quaint and picturesque, and for this reason inherently interesting,” Shapiro contends, “the agents of denominational benevolence necessarily saw Appalachian otherness as an undesirable condition and viewed the ‘peculiarities’ of mountain life as social problems in need of remedial action.”15

Capitalists, on the other hand, interpreted modernization to mean development of the region’s resources. Such development came to the mountains under the rubric of a New South Creed, a post-Civil War ideology emphasizing diversified agriculture, industrialization, and urban growth. The Creed was promulgated by native private speculators who had taken stock of the...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- To Save the Land and People

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations and Maps

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Introduction Common People and Private Property

- Chapter One Making, Taking, and Stripping the Land

- Chapter Two Our Country Would Be Better Fit for Farming

- Chapter Three Selfish Interests

- Chapter Four We Feel We Have Been Forsaken

- Chapter Five We Will Stop the Bulldozers

- Chapter Six The Dilemma Is a Classic One

- Chapter Seven Liberty in a Wasteland Is Meaningless

- Chapter Eight Getting More and More Cynical

- Chapter Nine Against the Little Man Like Me

- Conclusion Having to Fight the Whole System

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index