![]()

EDITORS’ AFTERWORD

The Holocaust left a legacy of fundamental questions that touch the core of human existence as it is reflected in Western, and primarily Christian, civilization, questions of God’s silence and of the indifference of those who professed to believe in a faith that affirmed the dignity of all human beings. Out of the ruins has emerged a bizarre tale, awesome in its irony—a tale worth telling and telling again. It is a story about the telling of a story, in fact about the telling of six million stories, or maybe six million tellings of one story of the implementation of a demonic design, the all-out effort of a technologically advanced civilization to first dehumanize and then exterminate an entire people. The story of the telling of the tale concerns tellers young and old, scholars and craftsmen, who, charged with a sacred sense of mission, sought to preserve the Jewish memory and to uphold the humanness of the victims in the face of an ingenious SS machine designed to strip them of their individuality and turn them into ciphers crammed into concentration-camp logbooks.

In the walled-in ghettos, behind the barbed wires of the concentration camps, on the bloody trails in the woods, and in stifling hideouts, the persecuted took time out from their bread reveries and snatched minutes from their nightmares to put down what their eyes had witnessed, what their hearts had felt, and what their minds had pondered. Gazing at these pages written in a babel of languages, one wonders what it was that motivated these obsessed witness bearers. Was it the instinctive response of an organism to the threat of extinction, or was it a manifestation of a collective consciousness rooted in a long tradition and guided by a historic imperative to remember and remind? A hint of an answer to these questions may be found in the following talmudic tale.1

In the year 70 A.D., as Jerusalem was under siege, surrounded by the Roman legions commanded by Vespasian, a passionate debate took place inside the walls as to whether they should come to terms with the enemy or keep on fighting. Rabban Yohanan Ben Zakkai, a recognized spiritual leader, counseled moderation. Since the Jews could not possibly defeat the mighty Roman legions, they should seek some accommodation. Subsequently, Yohanan managed to escape from the city. On reaching the Roman lines, the story goes, he encountered Vespasian, the Roman general, whom he hailed as follows: “Peace to you, O King, Peace to you, O Ring!” Rabban Yohanan’s greetings, we are told, turned out to be prophetic. For even as Vespasian was objecting to the bestowed title of king, a messenger arrived from Rome announcing: “The Emperor is dead, and the notables of Rome have chosen you Head of State.” As an expression of gratitude for his prophetic utterances, Vespasian granted Yohanan one request.

One might well expect that Yohanan would have asked for the release of his family, still under siege, or for the sacred religious relics and treasures lying in the temple. Instead, the request that Yohanan put to the newly appointed emperor was as laconic as it was portentous: “Give me Yavneh and its scholars.”

At this momentous juncture in Jewish history, Yohanan set his eyes on the future. It was phenomenal foresight. In deciding to save Yavneh, Yohanan saved the Jewish heritage from extinction. The words of the Torah that came from the school of Yavneh stimulated an impulse for the evolution of rituals and ceremonies exhorting the Jewish people to preserve the past in memory. As a consequence, it became possible, following the destruction of the Second Temple, to absorb the grief of the people and to convert it into a vehicle for spiritual renewal during the long period of exile.

Approximately 1900 years later in a continent far away from the land of Israel, the collective Jewish memory was again put to the test. In the shadow of the Nazi swastika, a contest was taking place between the perpetrator, who was determined to erase the memory of an entire people from the collective consciousness of mankind, and the persecuted, who were equally resolved to foil the oppressor, not necessarily by escaping personal extinction but by keeping and concealing historical records for the information of future generations, even when individual survival had clearly become impossible. Following in the footsteps of the biblical and talmudic tradition, the designated victims resorted to an unprecedented recording of their experiences. Ultimately, recording becomes synonymous with remembering and remembering with spiritual resistance. This three-stranded, braided cable of recording, remembering, and resisting is the quintessence of the following message delivered by Rabbi Nachum Yanchiker to his students at the Slabodka-Musar Yeshiva in the fateful year 1941:

My dear students, when the world returns again to stability and quiet, never become tired of teaching the glories, the wisdom, the Torah and the Musar of Lithuania, the beautiful life which Jews lived here. Do not become embittered by wailing and tears. Speak of these matters with calmness and serenity, as did our Holy Sages in the Midrash, “LAMENTIONS RABBATI.” And do as our Holy Sages have done—pour forth your words and cast them into letters. This will be the greatest retribution which you can wreak on the wicked ones. Despite the raging wrath of our foes, the holy souls of your brothers and sisters will then remain alive. These evil ones schemed to blot out their names from the face of the earth; but a man cannot destroy letters. For words have wings; they mount heavenly heights and they endure for eternity.2

As though she had been one of those students addressed by Rabbi Yanchiker, Sara Nomberg-Przytyk stored her Holocaust experiences in memory, and when the world returned to relative stability and quiet, she began to speak of these matters with calmness and serenity, and, for the most part, without bitterness and wailing. It is one of the still unresolved problems of that body of writings called Holocaust literature that the events seem to overwhelm all attempts to impose formal order, either of literary history or literary criticism. The problem of ordering, categorizing, and interpreting is further exacerbated by the perverse efforts of so-called revisionist historians who deny everything, deny that the Nazis exterminated millions of Jews and others, thereby placing an additional burden on those who wish to study the ways in which imagination modifies memory and fiction vitalizes history.

Among witnessing authors, Elie Wiesel is preeminent for his poetic and novelistic evocation of the death-camp experience. No one has labored more assiduously to reveal the multi-faceted reality of survivorship. Yet even Wiesel has recognized that sometimes it is only fiction that can make the truth credible, just as it is only imagination that can make memory tolerable. This vision is expressed in a dialogue between Wiesel and a rebbe, as reported in the introduction to Legends of Our Time:

“What are you writing?” the Rebbe asked. “Stories,” I said. He wanted to know what kind of stories. “True stories.” “About people you knew?” “Yes, about people I might have known.” “About things that happened?” “Yes, about things that happened or could have happened” “But they did not?” “No, not all of them did. In fact, some were invented from almost the beginning to almost the end.” The Rebbe leaned forward as if to measure me up and said with more sorrow than anger: “That means you are writing lies!” I did not answer immediately. The scolded child within me had nothing to say in his defense. Yet, I had to justify myself: “Things are not that simple, Rebbe. Some events do take place but are not true; others are, although they never occurred.”3

In reporting his conversation with the rebbe, Wiesel has pinpointed one of the major problems faced by witnessing authors in writing about the Holocaust. To tell the story as it “happened,” as unembellished, unadulterated “realism,” would strain the reader’s credulity, for the concentration-camp world was stripped of the basic premises constituting a normative society. The cause and effect link, for example, that defines our relationship to our surroundings was rendered inoperative in the concentrationcamp environment. The relative freedom that enabled a person to arrange his life within a causal context was brutally denied to the concentration-camp inmate. Consequently, the inmate was deprived of the psychological props indispensable to the individual in orienting himself to the world. Paradoxically, a swing to “pure” imagination would be equally inadequate, for to cast the camp reality into wholly metaphoric structures would undermine the historicity of the events. Since the relatedness of memory and imagination has only been touched upon with regard to Holocaust narratives, critics have not recognized that neither can be relied on as an absolute constant. Both are variables. The challenge to the witnessing author, therefore, is to use traditional mimetic forms to convert the repugnant, intolerable reality he witnessed into an intimation of reality that can be both accepted and tolerated by a sensitive, normatively oriented reader.

The credibility factor occupied the chronicler under siege as far back as 1941. Fearing that the depositions of victims in the Warsaw Ghetto would be received with skepticism after the war, Emmanuel Ringelblum instructed his chroniclers to adhere strictly to bare facts and to avoid emotional coloring in their reports. “Comprehensiveness was the chief principle guiding our work,” notes Ringelblum in his diary, “and objectivity was the second principle guiding our work. We aspired to tell the whole truth, however painful it may be.”4

About the same time, in the Lodz Ghetto, a high school boy by the name of S. Dratwa envisioned how producers would make a film of the Jewish tragedy after the war, predicting, at the same time, the kind of response the film would elicit from the audience. In his mind’s eye, he saw the audience watching the film:

Wrapt in emotion,

Quivering with pleasure,

Everyone will think:

“The film is fabulous,

The scenes are wonderful,

But nothing is true.

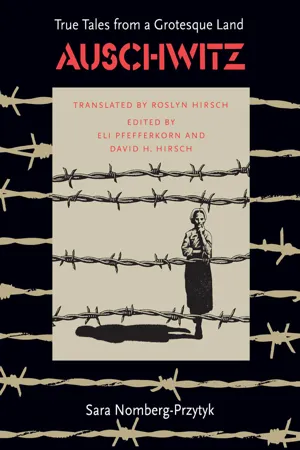

They are only tales from a grotesque land.”5

Unwittingly the young Dratwa posited the crucial question of how to portray a grotesque world and yet make it seem historically true. What the besieged Dratwa foresaw, Elie Wiesel survived to see, and having seen it, he has tried to caution the world against converting a historical event of immeasurable human pain into a merely grotesque fiction divested of its historic dimension.

Like Wiesel, Sara survived to draw her disturbing vignettes, and in drawing them to make the grotesque reality believable. She is a natural storyteller who has the capacity to render the unbearable tolerable by suffusing her narrative with a radiance of imagination, treading a fine line between history and fiction, between document and novel. The present editors and others who have read her “stories” have been startled by her ability to convey the most depressing materials without depressing the reader. She does this, we believe, with the skill of the novelist, creating the illusion of vibrant life and the will to live even in the kingdom of death, making her characters live in the reader’s imagination. And she accomplishes this feat with utmost economy in her brief vignettes.

Sara’s interest in character, however, is not Dostoyevskyan in nature. Rather, her characters exist as constituents of the death-camp reality. Though the individuals whom Sara recalls are often fascinating in themselves, each one is, nevertheless, anchored to a camp happening; consequently, it is the aggregate of the individual vignettes that structures the incarnation of the actual camp experience.

As an example of Sara’s storytelling art we would like to examine briefly the vignette entitled “Old Words—New Meanings,” which can be perceived as being in some sense a microcosm of the book as a whole. On casual reading, the vignette appears to be a simple, plainly told story of the young girl Fela. In telling Fela’s story, Sara exposes some of the grimmest aspects of camp life: sick, starving prisoners who must cheat each other to stay alive—an economy in which every scrap of bread one eats is life-bread taken from someone else, and not only is this the case but everyone who has a crust of bread knows this is the case; kanada, the gruesomely conceived warehouse storing belongings of the dead and those consigned to death; and finally, “selection” and the gas, the insane process by which people are more or less randomly inscribed for life or death by Dr. Mengele and his cohorts.

It is our impression, confirmed by other readers, that the horrors are not immediately perceived as such by the reader because of Sara’s narrative technique. She begins her story with a more or less abstract concept: the collapse of normative reality in the camps, which results in a corresponding disfiguration of language and a change in alignment between sound images and the concepts to which they refer. Specifically the word “organize,” a signifier normally associated with social order and well-being, has come to denote the activities involved in procuring the basic elements necessary to sustain physical existence.

Sara writes in the tradition of the Yiddish folktale. Though her stories are simply told, they stimulate the reader to contemplate complex issues that belie the apparent simplicity of the surface structure. Hence, in the tale at hand, she quickly roots the abstract notion of a collapse of reality reflected in a collapse of normative linguistic usage in the story of Fela, a young girl who learns not only the new meaning of the word “organize” but also learns how to “organize,” i.e. who becomes a master of the new reality. It is, of course, the reader’s consequent fascination with the character of Fela that pushes the ghastly aspects of camp life into the background, where they register on the subliminal consciousness. Consider, for example, Sara’s brief description of Fela and her situation: “Eighteen years old ... she had been sent to Auschwitz when she was caught smuggling food into the ghetto for her family. She was a tall, slim girl with very light blond hair. She was not a beauty, but she had a quality that was impossible to describe. Something forced you to look at her. She was alone, without family or friends, but in spite of that, she did not give the impression of being helpless.”

Though the sketch is drawn in a few brief sentences, the reader has already learned much about Fela. From the fact that she was caught smuggling food into the ghetto for her family, we may infer that she was courageous, resourceful, devoted, and not simply looking out for herself. We also learn something about the abhorrent conditions of ghetto life, where people were left to starve unless they engaged in the activity of illegal barter and two-way smuggling (the smuggling of valuables out of the ghetto and food back in). Avoiding the possible pathos of labeling Fela as “a beauty,” Sara nevertheless conveys an image of Fela’s physical attractiveness. She further engages the reader’s sympathy by writing that Fela “was alone,” revealing that the family for whom she had risked her life by smuggling had been exterminated. In conveying this information indirectly, Sara does not permit us to dwell on the depressing horrors but forces us, rather, to focus on the intriguing figure of Fela herself, and she arouses the reader’s interest furthe...