eBook - ePub

To the Webster-Ashburton Treaty

A Study in Anglo-American Relations, 1783-1843

- 271 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The Webster-Ashburton Treaty of 1842, which led to the settlement of the Canadian boundary dispute, was instrumental in maintaining peace between Great Britain and the United States. Jones analyzes the events that aggravated relations to show the affect of America’s states' rights policy, and he concludes that the two countries signed the treaty because they considered it the wisest alternative to war, not because of the often-claimed strategic distribution of money.

Originally published in 1977.

A UNC Press Enduring Edition — UNC Press Enduring Editions use the latest in digital technology to make available again books from our distinguished backlist that were previously out of print. These editions are published unaltered from the original, and are presented in affordable paperback formats, bringing readers both historical and cultural value.

Originally published in 1977.

A UNC Press Enduring Edition — UNC Press Enduring Editions use the latest in digital technology to make available again books from our distinguished backlist that were previously out of print. These editions are published unaltered from the original, and are presented in affordable paperback formats, bringing readers both historical and cultural value.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access To the Webster-Ashburton Treaty by Howard Jones in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Diplomacy & Treaties. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. The Great Northeastern Boundary Gap

Americans saw the dispute over the northeastern boundary of the United States as a major British challenge to their sovereignty because it foreshadowed certain Anglo-American rivalry over North America. Though most observers in the 1790s did not consider the boundary an important issue, the ensuing debate over its location highlights the fragility of the republic’s first decades. Despite the brave words of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, the grand philosophies of the first officers of the government, and the optimism among Americans in general, the experiment in New World republicanism might not have succeeded. Domestic opposition to the new national government is familiar to any student of American history. The opposition of foreign governments, especially that of Britain, has had less attention, perhaps because Americans have regarded their experiment in liberty as an internal proposition, unaffected by foreign nations. For years few European regimes looked upon the American government with respect, but the open disdain of the British was especially irritating. Americans believed, with little evidence, that London officials refused to consider either the Treaty of Paris of 1783 or the Treaty of Ghent of 1814 as a basis for good relations, and as a result did not move decisively to resolve the boundary.

Contentions between Americans and Britishers over the international boundary went on for more than a half century, and it is revealing to trace the course of the dispute as a case study of Anglo-American difficulties. From the end of the Revolution until the 1840s, the British seemed purposely to avoid a large view of the subject. The wording in the northeast boundary article of the Treaty of Paris was specific: “From the North West Angle of Nova Scotia, viz. That Angle which is formed by a Line drawn due North from the Source of Saint Croix River to the Highlands along the said Highlands which divide those Rivers that empty themselves into the River St. Lawrence, from those which fall into the Atlantic Ocean, to the northwestern-most Head of the Connecticut River.” But instead of resolving the question, the certainties of treaty language masked the uncertainties of North American topography, with long-lasting results. Indeed, these differences between Britain and the United States were not to be resolved until the Webster-Ashburton Treaty in 1842 finally ended the boundary dispute unwittingly created in the peace treaty of 1783.1

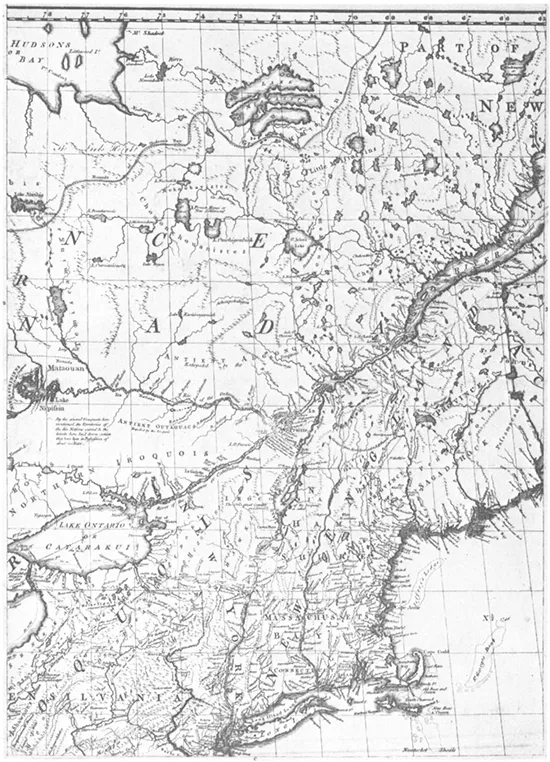

John Mitchell’s Map of North America (1775)

The many technicalities in plotting the northeast boundary generated the most serious Anglo-American arguments. The negotiators at Paris had used a 1775 impression of John Mitchell’s famous Map of the British and French Dominions in North America (1755), the best map of its time, but the lack of surveys had forced the cartographer to guess at the location of many rivers and to omit important mountains and other land features. The Paris delegates had started their boundary at the St. Croix River—but no waterway of that name existed on the east coast of North America. A dispute developed over which of the region’s rivers fitted the description of the St. Croix outlined in the treaty: the Schoodic in the west (the British claim), or the Magaguadavic in the east (the American). Title to some seven to eight thousand square miles of territory stocked with valuable timber and rimmed by a coastline allowing access to rich fisheries and vital waterways depended upon resolution of that problem.2

The Treaty of Paris created other cartographical problems as well. One concerned the northeast boundary’s “highlands.” Twenty years earlier the British government had used these slightly known ridges to divide the province of Quebec from Nova Scotia and New England, but they never had been surveyed. The treaty of 1783 specified a boundary that followed the highlands separating the flow of the waters of the St. Lawrence from those of the Atlantic. Did highlands mean mountains or only a watershed? This uncertainty caused another. The highlands formed the boundary to the northwesternmost head of the Connecticut River. No one afterward could determine which source of that river the negotiators meant. When Britishers contended for Indian Stream and Americans for Hall’s Stream, the disputation added 150 square miles to the boundary argument.

There were still other difficulties. One arose from an erroneous survey of the forty-fifth parallel, the boundary along the top of Vermont and New York westward to Lake Erie; during the War of 1812 the United States unknowingly constructed a fort at Rouse’s Point in British territory. Another question developed from the uncertainty of the international border running through the Great Lakes and to the Lake of the Woods.

Taken by themselves, these problems might have been susceptible to rapid solution; but they became intertwined with other matters to pose major obstacles to the establishment of harmonious Anglo-American relations.

In the period after 1783, Loyalists from Nova Scotia settled in the area between the Schoodic and the Magaguadavic and set off a dispute over the St. Croix that took a dozen years to resolve. The secretary for foreign affairs under the Confederation, John Jay, proposed a joint commission to settle the matter. Yet the British government rejected his overture—probably because it considered the entire subject relatively unimportant. Jay believed the situation was growing increasingly precarious and recommended that Massachusetts fortify key areas under “select and discreet officers” until Continental soldiers could take their place. Then, after adoption of the Constitution, the Massachusetts General Court in 1790 informed President George Washington that the British were encouraging settlers to occupy American territory. The president referred the question to the Senate, which soon repeated Jay’s earlier proposal of a mixed commission.3

But European affairs intervened. When the British and French governments went to war in 1793, new, more pressing problems arose. John Jay, by this time chief justice of the Supreme Court, sailed for London the following year to defuse an explosive quarrel that had arisen from British interference with American commerce. The northeastern boundary question remained at best a secondary concern of both governments, but the European situation pressured William Pitt to settle some of his problems with the United States. Jay, however, failed to exploit his momentary advantage. He was surprised to receive a warm welcome from the king and queen, who were so cordial that the envoy decided not to mention his reception to the administration in Philadelphia for fear that Anglophobes might think the British government sought only to deceive him.4 Southerners and Westerners remembered how willing he had been to forego navigation of the Mississippi River during the abortive negotiations with Spain in 1785–86. What could prevent him from giving up even more to win the favor of Britain, a country everyone knew Jay admired?

A small consequence of this British interest in rapprochement with the United States was a plan for settling the boundary, but even the business of resolving only a section from the Atlantic inland proved difficult. Jay’s Treaty of 1794 marked the beginning of the modern history of arbitration when it provided that a three-member joint commission determine which river flowing into Passamaquoddy Bay was the St. Croix. Each government would name a commissioner, and these two men would choose a third. Two Americans and a Loyalist residing in Nova Scotia began work in the autumn of 1796.5 Then the complications arose.

Almost immediately the Americans found themselves embarrassed, for they learned that the negotiators of 1782–83 had used a Mitchell map brought to Paris by the British representatives, a fact the American commissioner himself now uncovered by referring to letters written from Paris by Benjamin Franklin and John Adams. When the commission met in August 1797 at Adams’s house in Quincy, the former diplomat, now president of the United States, stated that the Americans had consulted other maps in their quarters, even though he admitted that in drafting Article 2 he recalled using only a Mitchell. When the commissioners asked Jay (who also had been in Paris) about the matter, he agreed. The American side made another damaging admission. Adams and Jay confessed that in placing the boundary the delegates at Paris, both British and American, had not considered Mitchell’s map conclusive.6

After considerable hassling, the commissioners succeeded in establishing only part of the northeastern boundary. The Schoodic, they announced, was the St. Croix intended by the treaty makers in 1783. The rest of the boundary, however, remained uncertain because there was no way to draw a line between the source of the St. Croix and the “highlands” mentioned in the treaty. No place in this northern area corresponded to the description in the treaty of 1783. A wide, irregular, elevated strip of land sprawled above the St. Croix, but there were no mountains. The British now claimed the St. John area, while the Americans argued that their country’s territory stretched north of the Restigouche River (143 miles north of the British claim), along a line twenty miles inland from the lower St. Lawrence. Including the area around the Connecticut River’s headwaters, the territory still in dispute after the commission filed its report in 1798 comprised a triangle of 12,027 square miles.7

The brief truce in the European war brought by the peace of Amiens in 1802 afforded a second opportunity to arrange the northeastern border. After the Americans informed British Foreign Secretary Lord Hawkesbury that they desired a settlement, their minister in London, Rufus King, a dignified, serious Federalist gentleman who expected immediate results in all affairs, received instructions to negotiate on the areas north of the St. Croix and through the Bay of Fundy. The United States appeared to have a good argument for several of the islands at the rim of Passamaquoddy Bay, but Secretary of State James Madison unfortunately made a tactical error in his directives that jeopardized his country’s position. After defining the highlands above the St. Croix as “elevated ground dividing the rivers falling into the Atlantic,” he wrote that the highlands of the treaty of 1783 were “now found to have no definite existence.”8

Out of this confusion came the King-Hawkesbury Convention of 1803. Madison’s instructions arrived in London in June 1802, a few days after King had departed on a three-month holiday in Europe. When the minister returned, he found difficulty in persuading Hawkesbury to devote time to the matter. At last came an understanding. There would be no problem in extending the line to the highlands, King wrote Madison with relief, as he and Hawkesbury had signed a convention for this purpose.9

The proposed agreement went to the Senate in October 1803, but with a message from President Thomas Jefferson that the northeastern boundary of 1783 was “too imperfectly described to be susceptible of execution.” Although Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin had urged approval, the president did not agree with Gallatin’s reasoning. Oddly, Jefferson had submitted the treaty but recommended its defeat.10

The convention already had little chance for passage, but its downfall came primarily because the negotiators also had tried to patch a sector of the Canadian-American boundary on the other side of the Great Lakes, between Lake Superior and the Lake of the Woods, and the resultant proposal got entangled in the Senate’s discussion of the Louisiana Purchase. The British agreement had arrived in the autumn of 1803, not long after Jefferson’s envoys had concluded the purchase treaty with Napoleon Bonaparte, and confusion quickly became apparent between the terms of the convention with Britain and the treaty with France. To deal with the matter, the Senate appointed a committee, chaired by the Anglophobic John Quincy Adams, and discussion soon focused on whether King and Hawkesbury had known of the purchase before signing the convention. Although King declared they had signed without knowledge, the committee decided that since no one understood the northern extremities of Louisiana it could not say whether there was conflict between the French and British agreements. Perhaps to salvage land claims farther north, the Senate in early February 1804 unanimously voted to accept all of the British convention except the portion concerning the Lake of the Woods boundary gap. The Pitt ministry, no doubt irritated with suspected American designs on Canada, refused this arrangement.

Other factors, such as resumption of the Franco-British conflict in May 1803, doubtless had an effect. There also may have been a mixture of American domestic politics. Jeffersonians, already suspicious of the British, perhaps had found their decision to vote against the convention easier because King was a potential presidential candidate on the Federalist ticket in 1804.11 The King-Hawkesbury Convention thus expired, buried in the Louisiana Purchase and other seemingly unrelated matters.

The Americans and British made one more attempt to settle the northeastern boundary before going to war in 1812. James Monroe, minister in London, and William Pinkney, special envoy, signed a treaty with the British government in 1806 that involved commercial matters. Evidence indicates that both men considered America’s commerce more important than any other subject. As a protégé of President Jefferson, Monroe cherished distinction in public service and might have signed almost any treaty with the British for the sake of accomplishment. Pinkney, a capable but stiff-mannered, cocksure lawyer, had been part of the Anglo-American commission established under Jay’s Treaty to settle cases involving British seizures of American ships. This combination of talents augured ill for American interests. In addition to the commercial treaty, the envoys in 1806 hoped to reach a separate agreement dividing the islands in Passamaquoddy Bay. Monroe and Pinkney believed they had arranged the second convention, but when they sent back the first treaty on trade, Jefferson would not submit it to the Senate because the British government had not renounced impressment. By this time desertions had made the British navy so hard put to find seamen that it had begun to take suspect sailors found aboard privately owned ships of the United States. An unrelated issue—impressment—thus destroyed not only the commercial treaty of 1806, but also the possibility of a second convention on the boundary. A change in the British ministry further complicated matters. The Tories came back into power in March 1807 and opposed any agreements with the United States.12

The foregoing discussion shows that the major obstacle to an early boundary settlement was the United States—not Britain, as Americans unjustly claimed. The St. Croix commission decided in favor of the British, and when a war-conscious ministry in London found time to work for an agreement on the relatively unimportant northeast boundary, the government in Washington stalled and eventually rejected the pact. Though the Louisiana treaty, domestic politics, and the emotionally charged issue of impressment clouded responsible assessments of the boundary, the Americans themselves confused the question and must bear primary blame for obstructing its resolution.

The War of 1812 was integral to the northeastern boundary question because it convinced the British that they needed a military road between the Maritime Provinces and Lower Canada. The provinces—Nova Scotia and New Brunswick—long had been a source of naval supplies, seamen, and ships, while Lower Canada had become increasingly valuable to the crown because of its farmland and fisheries. The problem was how to defend such territories, especially Lower Canada. London’s leaders could not rely on getting ships up the ice-choked St. Lawrence River in winter. During cold seasons British soldiers had marched on snowshoes through New Brunswick. Once they had maintained communication between Halifax and Quebec only by using a long overland route to the far north. In case of another war, British North America would be much more vulnerable to attack because of the expansion of roads and canals in the United States. During the winter the British might safeguard Lower Canada by maintaining troops at Kingston, Montreal, and Quebec, but without a fairly short overland route between the Maritime Provinces and Lower Canada, they could not reinforce the posts until spring weather opened the great river.13

The British effort to arrange better communication between the Atlantic Ocean and the Canadian interior began during the peace negotiations at Ghent in 1814. In the treaty of Christmas Eve, among other agreements, the two nations set up mixed commissions to deal with the boundary above the St. Croix, as well as with the undetermined sector between the Great Lakes and the Lake of the Woods. The American delegation—which included John Quincy Adams and Albert Gallatin—preferred to follow the precedent of Jay’s Treaty by having three-member groups—one from each country,...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1. The Great Northeastern Boundary Gap

- 2. The Caroline Affair

- 3. The Aroostook War

- 4. The Case of Alexander McLeod

- 5. Slavery and National Honor

- 6. Prologue to Compromise

- 7. The Peacemakers

- 8. Completion of the Compromise

- 9. The Maintenance of National Honor

- Appendix: The Webster-Ashburton Treaty

- Abbreviations

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index