![]()

1. A View of the Landscape

Mill on the Haw

“That was in the summer time, when the water gets low,” says Ethel Faucette (born just before the Christmas of 1897) as she remembers the first years of a lifetime’s work in the Glencoe Cotton Mill. “There’s a big old rock out there in Haw River they call Lily and—I forget the other one’s name, but there’s two of them. When you begin to see them two rocks, you’d know we was going to get a rest. Cause the water was getting low.”

“Yeah,” adds George Faucette, Ethel’s husband, “they made up songs whenever the water’d get low. Get out in front of the mill under two big trees—they done cut the two trees down. Get out there in the shade and sing.”

“Sometimes it was two or three times a week,” says Ethel, “when it didn’t rain. We had dry weather just like we have now. People say, ‘Oh, I don’t remember it.’ Well, I remember it very well, for I was working in the mill, and I know’d when it’d shut down for low water.”

The narratives of Ethel Faucette, her husband George, and their sons Don and Paul tell of three generations of life and work in the Glencoe mill village, located along the small and seasonally inconstant Haw River. Their memories lead back toward the turn of the century in historical fact, but they point even further back, glimpsing the region’s late-nineteenth-century transformation and, at moments, even evoking the tentative antebellum beginnings of Carolina Piedmont manufacturing.

“We run by water then, had water wheels. That was the power that run the mill. And when the water’d get low, maybe they’d stop off for an hour or two. Well, there was a crowd that would get their instruments and get out there in front of the mill. They would sing and pick the guitar and the banjo. Different kinds of string music. And maybe they’d stand an hour or two and the water’d gain up, and they’d start the mill back up.

“And I did have a piece that one man wrote about the whole mill. I lost it somewhere. He made up a song about the whole mill, but I forget what it was, don’t you, George?”

“What?”

“The song where, was it Walt Dickens—who was it made that song up about the mill? And it started at the first of it, where the cotton started in. From the breakers and the lap room and so on about the different kinds of work. He rhymed it up and made a great long song. But I can’t remember, been so long ago.”1

“I remember one time back in the Depression,” says Don Faucette. “Water was low and sometimes the mill would stand. Once when I carried the dinner up there, Daddy was standing out there up to his hips, getting the mud out from the back of the dam so the water would come down the race so they could go back to work.

“I remember well when they run the mill by water. Cause we had lights at Glencoe and at nine o’clock the lights went out. The mill furnished your lights and they’d come on about six o’clock at night and stay on till nine and then come on again at five in the morning and go out about seven.

“You’d be sitting there studying and the lights would go down. One of us would say, ‘An eel has hit the wheel.’ In a minute, that eel would grind up and the lights would go back on. There used to be some good fishing too in the Haw River. Until they turned that dye and stuff loose in Greensboro.”

“There was carps up there that weighed twenty-five pounds,” says Don’s brother Paul. “There was catfish, bream, bass, white perch. White perch is called crappie now. Blue gills, and oh, what did they call them with the red stomach? I don’t remember. We used to fish there until they started turning that dye loose up the river. After that, we’d have to go out there and rake the fish off the gates to let the water keep the mill running.”2

“My mother was Mary Elizabeth Marshall,” says Ethel Marshall Faucette, “and my daddy, he just had initials, M. M. Marshall. He was a twin and they named his sister Alice and Granny wanted him named David and Grandpap wouldn’t have it. So they just called him their “little man.” And that’s as much as he ever had. And he just signed his name M. M. Marshall. That’s the way he signed. It went that-a-way as long as he lived, [laughs] And it’s that-a-way in the cemetery.”

“Man” Marshall was born and raised on a Carolina Piedmont farm. When he died in 1939 at the age of seventy-two, he had held the superintendent’s job at the Glencoe mill for forty years. Like her seven brothers and sisters, M. M. Marshall’s daughter Ethel was working a ten-hour day in the Glencoe mill when she was more a child than an adult. She learned to operate the twisting and drawing-in machinery, earning $.85 a day when she began and $1.69 an hour by the time the mill shut down in 1954.

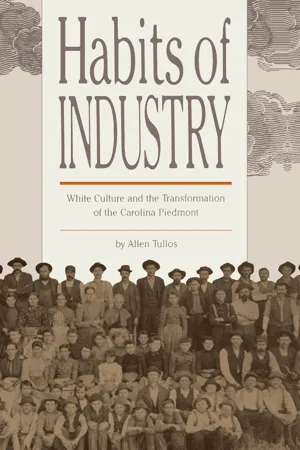

Mill workers at Glencoe, N.C., ca. 1900. Ethel Faucette’s father is the bareheaded man in the top row. Note the groupings and postures by gender and age. (Courtesy of Ethel and George Faucette)

“Daddy had a little better wages, but we didn’t,” says Ethel about the children of “Man” Marshall. “We fared just like the rest of the help. He made us do, and do right.

“And when we come from that mill, we didn’t sit at the table and talk about what the other fellow done down there—if we did we got our mouths mashed.

“He says, ‘You leave the mill out of your conversation.’ He didn’t allow us to say a word about it.”

The builders of the Glencoe mill and village, where the Faucette family worked and lived, were named Holt. The Holts, who had lived in the area since the mid-eighteenth century, were one of the Carolina Piedmont’s pioneering and prominent manufacturing families from the 1830s until their interest in the textile industry began to wane in the 1920s. Michael Holt, father of mill pioneer Edwin (1807-84), was a prosperous merchant, farmer, and slaveholder. It was on the site of the family’s power dam and gristmill that Edwin and his brother-in-law, William Carrigan, in 1837 built the first Holt cotton mill, a small operation with around five hundred spindles and no looms.

To propose the construction of a factory in the Carolina Piedmont in the 1830s required outlandish views. But Edwin Holt was persuaded by the success in that same decade of Henry Humphries’ steam-powered Mount Hecla Mill in Greensboro and by the encouragement and support of prominent North Carolina jurist Thomas Ruffin, a longtime family friend. Holt’s father bitterly opposed the project at first but lived to salute its profits.

Critical to the successful operation of antebellum Southern factories such as Edwin Holt’s and Henry Humphries’ was Yankee machinery and technical assistance. A Paterson, New Jersey, firm supplied Edwin Holt’s first mill and sent a machinist who supervised the installation of equipment and remained for a year and a half to give instruction in its running and maintenance.3

As they did in other antebellum Carolina Piedmont factories, white girls and women from the immediate neighborhood made up most of the labor force at the Holt and Carrigan mill. In the five cotton mills operating in Alamance County in 1850, there were 155 women workers and 33 men. Revealing the low status of factory work and the pitiful regard given to women forced into it, a traveler through Alamance in the 1840s wrote that a mill job was generally seen as a “blessing,” an unanticipated bit of good fortune, giving “employment and comfort to many poor girls who might otherwise be wretched.”4

Throughout the antebellum era, yeoman farming embodied the ideal of domestic independence in the Carolina Piedmont. Not until the long agricultural collapse that, in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, began to uproot farmers from their traditional livelihood could mill owners recruit an increasing number of male “hands.” As entire families moved to the villages, they often arrived with some sense of failure and with a strong determination to return to farming as soon as they could save enough money to buy the land. Neither factory wages nor agricultural conditions, however, favored a return to the land.

Antebellum manufacturer Edwin Holt cast an early eye to possible markets outside the county and even outside the Carolina Piedmont. In the 1850s an itinerant French dyer taught Holt and his son Thomas the process of dying yarn. Successful sales in the North of “Alamance Plaids,” the South’s first colored cotton cloth woven on power looms, assured the Holts’ wider reputation and success.5

In 1849, in a display of his new status and orientation, E. M. Holt built his home, Locust Grove, from the design of a New York architect. Locust Grove, notes architectural historian Carl Lounsbury, “was the first known house constructed in Alamance County which owed nothing in its plan and arrangement to the local building practices. It was the first clear-cut example of popular architectural tastes supplanting the vernacular tradition and foreshadows similar developments in the last half of the nineteenth century.”6 In his business and his tastes, Holt looked to markets and influences beyond the Piedmont, a wider world that would not find full entry into the region until after the Civil War.

Holt mills prospered through the war years, producing cloth for the Confederates. Then, reaping the rewards of established pioneers, Edwin Holt and his progeny refurbished their old factories and built several new ones in the 1870s and 1880s, mills that made fortunes for several branches of the family. Because of their small sizes and inconvenient locations, though, they were eclipsed, near the century’s end, by a new era in Carolina Piedmont manufacturing. The newest New South mills housed tens of thousands of spindles and hundreds of looms and sat alongside railroad spurs and trunklines.

Like Randolph County (to the southwest) with its Deep River and (still further west) Lincoln County with its many fast-running creeks, Alamance County and the Haw River offered tempting locations for the Carolina Piedmont’s antebellum experiments with cotton factories. Like the Holt mills, the first generation of Carolina Piedmont cotton factories (a handful of tiny mills built between 1813 and 1830) emerged out of the region’s tradition of home weaving and its experience with water power for the grinding of grain and cereals. These early cotton mills were begun in order to supply yarn for domestic weaving in the surrounding communities. Transported by wagon, bundles of coarse yarn were sold and bartered throughout the region and into the Southern Appalachians. The tiny antebellum factories were vastly outnumbered in a landscape dotted with gristmills and sawmills, centers of community life that stood along every good-sized creek.7

Unlike the major rivers of the Carolina Piedmont, which begin in the Appalachians and are fed over a wide watershed, the Haw, which furnished power to the Holt mills, rises in the Piedmont counties of Rockingham and Guilford and depends for its water level on local rainfall. The flow of this bedrock-bottomed stream varies dramatically from week to week and, as Ethel Faucette remembers, predictably from season to season. The power to drive the Piedmont’s industrial emergence did not lie in the Haw or in the Deep River, but with mightier waters to the west, such as the Yadkin and the Catawba. Around the turn of the twentieth century, these rivers spun the turbines of a regional power network under the control of James B. (“Buck”) Duke’s new electrical company.

In 1880, about the time that the Glencoe mill, with its 3,000 spindles and 180 looms, began operation, several Carolina Piedmont mill builders had already begun to shift away from the beside-the-old-mill-stream mentality toward one of increasingly larger, beside-the-railroad factories relying on coal and, soon, electricity. In addition to the advantages offered by railroad access and cheap power, a search for available labor also appears to have promoted the location of new, large mills in areas of the Piedmont where the cotton farming crisis was felt most severely.8

When they built Glencoe, a three-story mill that was fifty feet wide and two hundred feet long, the Holts also built a mill village. Lined along two streets, more than three dozen two-story hall-and-parlor houses were solidly constructed of wood and drew upon a folk architectural form widespread among antebellum Piedmont farmers. Between the inside and outside walls the builders added a layer of insulating brick nogging. At the rear of these houses stood separate kitchen buildings, also in vernacular form. Rows of white oak, the Carolina Piedmont’s signature tree, grew to shade the streets.9

In 1880 the six hundred mill workers in Alamance County accounted for 18 percent of North Carolina’s entire textile work force. Forty years later, Alamance counted three thousand mill hands, but these comprised only 3.2 percent of North Carolina’s ninety-four thousand textile workers.10 When it closed in the mid-1950s, after decades of pounding out coarse fabrics, the Glencoe mill was tiny by contemporary standards, holding only four thousand spindles and two hundred looms.11

The modern textile manufacturing companies of the Carolina Piedmont left Glencoe and scores of similar mill villages behind, touchstones to an earlier era of localism. Once, they had helped shift the mainstream of a region’s way of life. Then, having no railroad, sitting astride no major highway, losing the early advantages of their water-power sites, suffering the neglect of their owners, unable to recruit sufficient workers, and failing to modernize their machinery, the Glencoes were pushed into the eddies. As such towns lingered—places with names like Bynum, Orange Factory, and Coleridge—the shapes and materials of their houses and the memories of their abiding residents recalled lost heydays.12 The newer Piedmont spread away from the side roads and sought the major rail and U.S. highway axes.

“It was so far back when I told this,” says Charles Murray, another of the handful of Glencoe holdouts. “But I did it as a joke. I’d hear people tell it. There’s some fish in the river they used to call terkel. And the mill would send a wagon off and get terkel and they’d come back and pay you off. They’d give you a big terkel. And you’d go to the store and buy anything, and you’d give them a big terkel and they’d give you little terkels back.”13

“People then just thought they was fortunate to be working,” says Ethel and George Faucette’s son Don, himself a textile worker in nearby Burlington. Born in 1925, Don remembers growing up in a Glencoe that seemed stunting and isolated. “To have food on the table and clothes on their back and a roof over their head, that’s all that mattered. I mean, that’s the reason I wanted to get me a car and get out, just like a bunch of us did. Old Ed King and Vann Kerr and all of us, we wanted to have something, you know. And we just felt like we couldn’t have nothing staying over there at Glencoe.

...