- 440 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

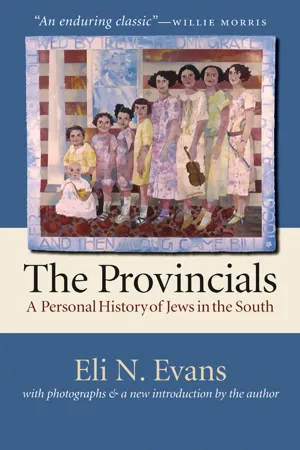

In this classic portrait of Jews in the South, Eli N. Evans takes readers inside the nexus of southern and Jewish histories, from the earliest immigrants to the present day. Evoking the rhythms and heartbeat of Jewish life in the Bible belt, Evans weaves together chapters of recollections from his youth and early years in North Carolina with chapters that explore the experiences of Jews in many cities and small towns across the South. He presents the stories of communities, individuals, and events in this quintessential American landscape that reveal the deeply intertwined strands of what he calls a unique “Southern Jewish consciousness.”

First published in 1973 and updated in 1997, The Provincials was the first book to take readers on a journey into the soul of the Jewish South, using autobiography, storytelling, and interpretive history to create a complete portrait of Jewish contributions to the history of the region. No other book on this subject combines elements of memoir and history in such a compelling way. This new edition includes a gallery of more than two dozen family and historical photographs as well as a new introduction by the author.

First published in 1973 and updated in 1997, The Provincials was the first book to take readers on a journey into the soul of the Jewish South, using autobiography, storytelling, and interpretive history to create a complete portrait of Jewish contributions to the history of the region. No other book on this subject combines elements of memoir and history in such a compelling way. This new edition includes a gallery of more than two dozen family and historical photographs as well as a new introduction by the author.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Provincials by Eli N. Evans in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Jewish History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

part one

TOBACCO TOWN JEWS

1

An Inconsequential Town

Durham as I recall it was an ordinary-looking town precisely divided into five pie-shaped sections, spreading out from Five Points, our “Times Square.” Here five streets converged, and buses rumbled through all day, radiating in all directions so that a downtown shopper could climb on a bus home no matter where he lived. Every section had small pockets of black settlements, some no larger than three or four streets, but for the most part, the neighborhoods stayed to themselves, each with its own character.

First was Hayti (named after Haiti, I was always told, but pronounced “Hey-Tye”), where the Negroes lived alongside Fayetteville Street, lined with cheap grocery stores advertising catfish, fatback, and greens. The exotic store-front cults and the gypsy palmists added mystery to the neighborhood, while a lavish funeral home provided a touch of glamor, with its shiny hearse parked out front for advertising purposes. There were beer joints like Papa Jack’s and the Bull City Sandwich Shop; little places like Pee Wee’s Shoe Shop and the Two Guys’ Cut-Rate Drug; and a movie theater featuring World War II films, with a homemade sign out front that said “White Section Inside.” Middle class or poor, the blacks lived in Hayti. The beautiful homes of the North Carolina Mutual Insurance Company executives, who worked for “the largest Negro-owned company in the world,” clustered on the paved streets around North Carolina College ; on the next block, crumbling shanties lined the dirt streets. On every corner throughout stood the churches, some brick and manicured, others as rundown as the congregation—St. Mark A.M.E. Zion Church, Fisher’s United Memorial Holy Church, and the United House of Prayer for All People, “Bishop C. M. Grace, Founder.”

Only the railroad tracks separated the working whites of East Durham from the blacks in Hayti—fifteen feet of parallel steel that might as well have been a gorge as deep as the Grand Canyon, except on Saturday nights when carloads of young whites might wheel through. The white millhands lived in clapboard dwellings with green shutters and small yards, their cars parked on the street because they didn’t have garages. They too had churches on almost every corner, diners that advertised cold beer and grits and eggs, pool rooms, hardware stores, and Jimmie’s Soda Shop, all surrounding the city softball field, where on most summer nights you could watch a girls’ team or a Little League game, the name Erwin Mills or Liggett & Myers emblazoned on their jerseys.

West of Five Points, the red brick tobacco warehouses ringed the downtown, sometimes suffocating the city with the thick pungent odor of aging leaves, which we were conditioned to call “a rich aroma.” Just beyond the factories and Durham High School, lived the middle class, in brick homes with postage stamp lawns that the young blacks mowed for a dollar. Most of the Jews who were not associated with Duke University lived here, though a few were audacious enough to try Hope Valley, even though they couldn’t belong to the country club out there. The old Trinity College campus and the new Duke University provided a rolling green corridor to the Duke woods and the homes of the college administrators and the professors, puttering around in their azaleas on winding streets that valued a dogwood tree above all else.

Hope Valley was the home of the newly rich—the owners of the lumber companies and the corporation lawyers, the bank officials and the successful insurance salesmen, their white-columned or ranch-style homes surrounding the Hope Valley Country Club golf course. Any day you could see men in colorful outfits chipping up to a green out on the fairways. Their daughters were debutantes who entered the horse shows down in Pinehurst but mostly lolled around the pool at the club; the society page featured their wives during the Junior League fashion show.

The older rich lived in Forest Hills around a park that John Sprunt Hill had given to the city after he married the daughter of an American Tobacco Company executive and made his own fortune in banking and insurance. My parents’ ambition had been to live in Forest Hills and they bought a lot there in 1939, across from the estate of Mary Duke Biddle. My father would take me there to walk around the trees where we were going to live someday, on a hill as high as the Dukes lived on. During the war my mother would rip through House Beautiful and Better Homes and Gardens, tearing out pictures and ideas until she felt she knew exactly what she wanted—her “dream house.” When we finally built it in 1950, it was the first split-level in town—so modern that the workmen brought their families out on Sunday to show them what unusual plastering and woodwork they had done that week. Even Mrs. Biddle ordered her limousine over for a look in, a triumph for the first Jewish family in Forest Hills. For our family 1950 was a special year—a new home and my father’s first campaign for mayor of Durham.

My father always cared about his town, and it seemed that any time money had to be raised, Durham called on him. He was part of the generation that was too young for World War I and too old for World War II, the men left at home to carry the brunt of community work to buttress the war effort. He headed the Community Chest campaigns; he brought all the hostile political groups together to pass the bond issue for the new wings on the white and Negro hospitals; he twice headed the war bond campaign; and he even persuaded Judge Spears to serve as chairman of the United Jewish Appeal and raised $8,000 from the gentiles when other Jewish leaders in North Carolina were too timid to ask non-Jews for money.

In 1950, as the new president of the Merchant’s Association, Dad was invited by the mayor to serve as one of the business representatives on the Citizens for Good Government Committee, a small group of leaders from the business community, labor, and the Negro political group who had formed to try to convince better candidates to run for local offices. Two days before the filing date for the spring election, the incumbent mayor received a federal appointment, and the key members of the committee began to cast around for a new candidate to replace him. Meeting followed meeting, but they could agree on no one. Finally, John Wheeler, the president of the Mechanics and Farmers’ Bank and chairman of the Durham Committee on Negro Affairs, asked, “What about Mutt Evans?” John Stewart and Dan Martin, the other leaders of the Negro organization at the meeting, said, “Evans helped build the Negro hospital and his store has been the only place where Negroes downtown can get something to eat or use a restroom.” They also recalled that when he directed the Community Chest campaigns, he had been the first white ever to go into the Negro community to sit and eat with several hundred Negroes at their kick-off chicken dinner, a symbolic act in a Southern town in the 1940’s.

My father was the only candidate that all the factions could agree on, but after the meeting the conservative members of the business group balked at endorsing anyone that the Negroes and labor trusted. They decided to run Judge James R. Patton against him, a canny corporation lawyer who had served as chairman of the Democratic Party in Durham until he was ousted by a new labor—Negro coalition several years before.

The newspapers announced the potential candidates, and some alarmed members of the Jewish community began calling my father to beg him not to run. They feared that if anything happened in the city, the whites would blame the Jews and that a divisive campaign might sink into an anti-Semitic slugfest that could cause racial unrest, threats to their business, and ugly incidents.

He decided to run anyway, on a platform of bringing the city together, but the “downtown crowd,” of which he, ironically, was a leader, opposed him vigorously. As election day approached, The Public Appeal, a small local paper with a workingman’s readership and run by vitriolic “Wimpy” Jones, published the fake Protocols of Zion, under a headline that suggested Durham was becoming part of a Jewish plot for world domination. When Joe Brady from New York, an old family friend whose father had been one of Buck Duke’s cigarette rollers, sent a contribution, a whispering campaign started to the effect that Evans was the “puppet” of a group of wealthy New York Jews.

A minor candidate forced a first primary, and the results opened my father up to a new kind of attack. He had received overwhelming support from the black precincts, and ads began to appear in the paper asking, “Who will choose your city servants? The Political Bosses, the Negro Bloc? or . . . You!” and “What has Evans promised the Negro Bloc?”

The Public Appeal put it more directly in an article entitled “NAACP Aims,” which said that the organization “through Communist influence” sought “getting addressed in the white press as Mr., Mrs., or Miss; picture publication, ... their weddings and social activities noted ... the designation ‘Negro’ eliminated from ALL court and public records ... [so that] they can really revel in all sorts of crime from rape to murder, and abolish all laws which prohibit Negro children or youths from attending general public schools and universities.”

It was classic racial politics in the small-town South; my mother worried about the personal threats, the obscene phone calls, and the wildly scribbled letters. The week before the election the police set up a twenty-four-hour watch on our house.

“Don’t worry, Sara,” my father tried to reassure her. “It’s not that serious. Just a precaution. Nobody means all that stuff and nobody pays any attention to Wimpy. It’s all just part of the game.”

“Politics blossoms like the dogwoods,” they say each May, but we didn’t even notice the final afternoon of the campaign as my father took me along with him from precinct to precinct to buck up the people handing out the “Evans for Mayor” leaflets. At Hillside High in Hayti the black poll workers greeted him excitedly, and one of them secretly showed us the sample ballot being passed out to all the black voters by the Durham Committee on Negro Affairs. I beamed—“Evans” was circled in red.

But over in East Durham in the poor white districts, and out in Hope Valley with the bankers and the businessmen, volunteers pulled him aside so as not to offend the young boy with him, and reported that the whispering campaign against him was working. I picked up enough to understand. “It’s rough out here, Mr. Evans, I don’t mind telling you.”

My memory of that campaign rivets on a tissue-thin pink leaflet showing a photograph of our new house just below big black letters: “Do We Want a Goldberg or an Evans? What’s the Difference? They’re All Alike.”

The house ... Would they do something to our house? Was my father in danger from a campaign that he had told me would be “fun”? Fear and ugliness engulfed my previous fantasies of adulation and victory. And then for the first time (a ridiculous thought in retrospect), it hit me that people thought “Evans” didn’t sound like a Jewish name.

The man who printed the leaflets also did signs for our store and he had sneaked my father a copy. They would not be distributed, Dad explained, because there were decent people supporting his opponent, including the big lawyer Percy Reade, who had promised him that the leaflets would never leave the print shop.

My father believed that openness and pride were the best political means of combating anti-Semitism, so he printed on his posters: “Chairman, Statewide United Jewish Appeal Campaign” and “President, Beth-El Synagogue.” “With our name,” he explained, “we have to go out of our way to let people know. And besides, people down here respect church work.”

So I remember my relief when the leaflet campaign was squelched. And I remember a secret thought too—I was glad that my name wasn’t Goldberg.

As the campaign progressed, the opposition took ads charging that the candidates running on the new reform ticket my father headed were “the tools of the Negro bloc vote,” and rumors began circulating that he had received campaign funds from “the New York Jews.”

The Sunday before the election, two ministers from the largest Baptist churches preached sermons deploring the inclusion of racial and religious issues in the campaign, and said they personally intended to vote for Evans. The night before the election, Dad went on the radio and was introduced by Frank Hickman, the most popular professor in the Duke Divinity School, who said, “I want to introduce a friend of mine, a great humanitarian, and invite you to vote for him for mayor tomorrow.” Dr. Hickman taught preaching to student ministers, and his voice reverberated with the righteousness of the hills of Judea.

Dad came on strong. “I ran to instill the same harmony in government affairs as we have had in civic affairs,” he said to emphasize his chairmanship of two successful war bond campaigns. “If we are to attain unity in Durham, each individual must be judged on his merit alone, and we must stop arraying class against class, labor against management, race against race in a vicious cycle of resentment. If I am fortunate enough to go into office on May eighth, I will go as a representative of all the people, regardless of faith, creed, or position in life.” Mom and I sat in the living room listening; she touched my arm as the band struck up “Marching along together, no one’s gonna stop us now.”

On election day, our black maid Zola voted early and Dad asked her at breakfast how things were going at the Hillside High precinct. She was so excited she could barely get it out. “Mister Evans, they’s lined up from here to Jerusalem, and everybody’s votin’ for you. ”

We came back home in the late afternoon to sweat out the rest of the day with Gene Brooks, a crafty former state senator whose father had been one of the most progressive leaders in behalf of Negro education in the state. He was our family lawyer, political adviser, and campaign manager. Today, he had turned our living room into a command post with an extra phone to dramatize its new purpose, and both phones were jangling away.

“It’s for you,” he said, handing the phone to Dad.

Dad went pale listening and told the caller that he would talk to Gene and get right back to him. “He says there’s a guy at the Fuller School precinct giving out razor blades to every voter and telling them to cut the Jew off the ticket.”

Fuller School was a workingman’s precinct where the struggling labor unions might sway a few poor white voters back from the reaction against any candidate with black support. Gene called Leslie Atkins, the controversial labor leader who had brought the Negroes into Democratic Party politics, put them in charge of their own precincts, and generally held the always frail Negro-labor coalition together. An hour later, Leslie called back.

“One of the boys took care of it,” Gene said. And then with a puckish grin, he admitted, “They just slipped that fellow a bottle of liquor and he’s finished for today—passed out.”

The ballots were counted by hand, and at eleven o’clock Dad was far behind. Then the Hillside precinct came in: Evans 1,241 and Patton 64. Gene whooped, “I bet Jackie Robinson couldn’t have done better.” Then he added, “I wonder where those sixty-four votes came from. I’ll have to get after somebody about that.”

Pearson School, the other large Negro precinct, came rolling in at 833 to 29, and Dad was also doing well at the Duke University precincts where the “innylekchals,” as Gene teasingly called them, were voting more heavily than usual.

When the radio announcer gave the final results in the mayor’s race at 6,961 to 5,916, officially confirming the phoned reports from the precincts, Dad turned to my mother and kissed her. “I told you that it would all work out. How does it feel to be the first lady of Durham?”

Mother was heading for the kitchen to put some food on the table for the few friends who might drop by when suddenly the door burst open and a gang of people from the Jewish community came thundering through, straight from an election night party at Hannah Hockfield’s. Fifty or sixty strong, buzzing with excitement, kissing me and messing my hair, they went roaring through the kitchen and out to the dining room, like a starving army of locusts, and just as suddenly, they were gone, the table in the dining room stripped totally bare.

The next morning when the phone rang at breakfast, Zola answered with a resounding, “Mayor Evans’ resee-dense,” and Mother blushed at Dad across the table. Nobody had instructed Zola in the new greeting, but nobody ever corrected her either.

Dad served for twelve years, in six consecutive two-year terms, through the turbulent fifties when the Supreme Court jolted the South into responsibility and changed all the rules of living. He played the role of peacemaker, presiding over transition years until blacks would demand concessions as a human right and whites would yield as an economic and political necessity. He always tried to guide his town, pleading for respect for the law and the courts, seizing the openings, and bringing his slice of the South through the difficult times when whole corners of his universe were turning to demagogues and false prophets for comfort and defiance.

The South is filled with quiet heroes who worked skillfully behind the scenes, who understood the levers of change and did what was right because deep inside they knew that the South could go only one way. The literature of the South would focus on the confrontations and the failures, not on the plodding, indefatigable and unheralded work of the men in places where the passions did not explode, nor death and hatred spill out for the probing, eager lenses of the media. It seems so inconsequential in retrospect, but the story of the South is written in the first, faltering steps in a hundred “inconsequential” towns: my father would be proudest of the first Negro policeman and fireman, the moving of Negroes into supervisory positions in City Hall, and the years he hammered the City Council to set up the Urban Renewal Authority to build low-cost housing for the poor of both races, leading to the largest federal grant in the South at that time because Durham could claim to be a pioneer. He worked behind the scenes to settle the first lunch counter demonstrations. (“Did the roof fall in today?” he asked the reluctant manager of Woolworth’s after they served a Coke to their first black student.) He badgered the merchants to hire Negro sales personnel, knowing that if all would move together, no one would be hurt and the community would be better off. He always had respect for the other man’s position, and would talk and work while some leaders sought momentary advantage by denouncing each other in emotional headlines.

There were the nasty fights on property taxes and garbage collection and fluoride in the city water. (“Mr. Mayor,” the rasping little old lady phone caller said, “I’m suing the city for damages because the fluoride has turned my teeth green and is making my heart palpitate,” and he answered, “That’s fine, ma’am, but we’re not putting it in for another month.”) There were the victories, like building the off-street parking garage and parking lots downtown to save it from drying up, ten years before others saw what shopping centers and suburbs were going to do. Even at that, to get the project launched Dad had to go out and sell the bonds personally, and reduce the estimated costs for parking a car from 40 cents to 10 cents an hour (by selling the bonds to...

Table of contents

- Table of Contents

- Praise

- ALSO BY ELI EVANS

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Foreword

- Introduction

- The Beginning

- part one - TOBACCO TOWN JEWS

- part two - THE IMMIGRANTS

- part three - THE STRUGGLE AGAINST CONFORMITY

- part four - COMING OF AGE

- part five - DISCRIMINATION

- part six - JEWS AND BLACKS

- APPENDIX A - Jews Elected to Office in the South, 1800-1920

- APPENDIX B - Jews Elected to Public Office in the South, 1945-1973

- APPENDIX C - Shifts in Jewish Population in Southern States, 1937-2000

- Acknowledgements

- About the Author