![]()

1. Called For and Delivered

~ June 1898–February 1933 ~

The gifts that would turn Eunice Waymon into Nina Simone were apparent by the time she was three, though the passions, the mood swings, and the ferocious intensity that marked her adult life were buried for years under her talent. She was born on February 21, 1933, the sixth of eight children, in Tryon, North Carolina, a town perched at the border between North and South Carolina, on the southern slope of the Blue Ridge Mountains. The beautiful surroundings, the pleasant climate, and the good railroad service established by the turn of the century helped Tryon grow from a rural outpost to a haven for white artists and their friends, many of them from the North. Visitors stayed and put down roots, those with keen business instincts making investments that gave the town its municipal backbone.

Eunice’s birth certificate listed her father, John Davan Waymon, as a barber and her mother, Kate Waymon, as a housekeeper. But these descriptions, necessitated by the limited space on the state’s official form, failed to capture the creative, entrepreneurial path John had woven through a world both circumscribed and defined by race. Likewise, “housekeeper” did not do justice to the pursuits of his equally determined wife to stretch the boundaries of their lives and give the family its spiritual core.

They were respected members of black Tryon and were treated with the patronizing courtesy whites traditionally reserved for those black residents deemed “a cut above.” The Waymons set an example of hard work for their children, underscored by a deep faith that from Kate’s perspective could ease disappointment and loss. Eunice had her doubts, and in her troubled moments as an adult, she would take little solace from her mother’s lessons. Her father’s buoyant spirit and pragmatic outlook, on the other hand, drew her in. “He was a clever man,” she recalled. “Although he wasn't educated, he had a genius for getting on.”

John Davan Waymon and Kate Waymon came from South Carolina, each the descendant of slaves. John, born June 24, 1898, in Pendleton, a small town near Clemson University, was the youngest of several children. A gifted musician, he played the harmonica, banjo, guitar, and Jew’s harp. “He could take a tub and make music out of it,” one of his children would say later with evident admiration, noting, too, that his father had the unique ability to whistle two notes at once. “We could hear that many blocks away—Daddy whistling in the night.” Tall, with a high forehead and prominent cheekbones, he looked the part of the song-and-dance man he became in his teens, dressed in a sharp white suit, spats over his shoes, cane in hand when he entertained the locals.

Kate was born November 20, 1901, and christened Mary Kate Irvin (though some family members spelled it Ervin), the baby among fourteen children—seven girls and seven boys. She was never sure what town her parents lived in when she arrived, only that it was in South Carolina, probably Spartanburg County. Her father was a Methodist minister, and while her mother was not officially trained, she had absorbed enough religion to carry on the ministry if Reverend Irvin was called away. Kate’s heritage on her mother’s side was an unusual mix. She took after her maternal grandfather, who was a full-blooded Indian, tall “and of the yellow kind,” as she recalled, and her maternal grandmother, who was short and dark with luxuriant black hair, which Kate inherited. She often wore it in a braid wrapped around her head.

One of Kate’s sisters, Eliza, was married to a pastor who led the congregation in Pendleton where John Davan worshipped. Sometime in 1918 he introduced John, then twenty-one, to Kate, only seventeen. Kate remembered that they sang “Day Is Dying in the West” together at church. John was smitten, and he promptly wrote Kate asking to visit her in Inman, where she now lived with her widowed mother. On that first visit they went for a buggy ride, and soon John was coming by every Saturday and staying through Sunday evening. Their routine on these visits usually included a ride in the countryside, the couple entertaining themselves with duets. Kate’s alto blended easily with John’s tenor on their favorites, “Whispering Hope” and “Sail On.” At the Irvins’ they sang around the little organ Mrs. Irvin had bought for her daughter. She paid for a few lessons, and then Kate taught herself the rest.

Few of their friends were surprised when John and Kate married in 1920. They moved to Pendleton to live briefly with John’s mother, and then they settled back in Inman. Their first child, John Irvin, was born in March 1922. The year after that Lucille arrived, and then came the twins, Carrol and Harold. When he was just six weeks old, Harold contracted spinal meningitis. He wasn't expected to live, but he survived, with a permanent paralysis on one side.

Though he still loved music, John gave up entertainment to take a job in a dry cleaning plant. He learned the business so quickly and with such thoroughness that he decided to open his own shop. He was also a part-time barber, and to earn extra money he took on work as a trucker. Just as important, he moved comfortably between the worlds of black and white, reaping rewards on both sides of the color line. He prospered enough in Inman so that Kate could stay home to take care of the four children. She even found time to take piano lessons to burnish her natural talent.

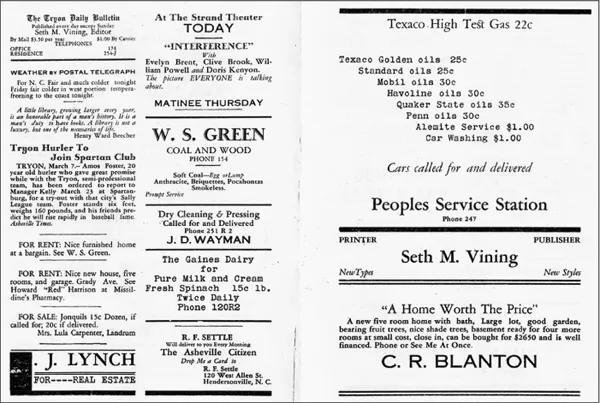

On one of his truck-driving jobs, John took a load of goods into Tryon, and right away he saw business opportunities for someone with ingenuity and energy. Years later the children remembered the prospect of opening a barbershop as the family’s reason for moving, but more likely it was the chance to run a dry cleaner’s that would serve the burgeoning tourist trade. John, Kate, and the children moved to Tryon early in 1929, taking a small house just off the main street. John opened his shop as planned, proudly announcing in a small ad in the Tryon Daily Bulletin “Dry Cleaning and Pressing—Called for and Delivered.” He even had a phone and listed himself by his nickname, “J.D.” Waymon. On March 7, not long after settling in, Kate gave birth to Dorothy, her fifth child in barely seven years.

An ad for J. D. Waymon’s dry cleaning shop (name misspelled) in Tryon, North Carolina, March 1929 (Tryon Daily Bulletin)

THE FOUR GAS STATIONS—Gulf, Sinclair, Texaco, and Standard—on Trade Street, Tryon’s half-mile-long main street, testified to the town’s prosperity, as did the two livery stables that served the hunt-and-riding set who rode the bridle paths through the town’s hilly outskirts. The two large hotels built years earlier were still thriving, and their success meant steady work for Tryon’s black community as waiters, housekeepers, and gardeners. Though the geography differed, the atmosphere evoked “that familiar hospitality of the Old South,” as one travel writer noted in The Charlotte Observer, North Carolina’s largest newspaper. “You envision snow-white linen, gleaming silver service and sparkling crystal, a smiling colored waiter, and you imagine you can smell the tantalizing odors of a delectable plantation dinner….”

The heart of Tryon’s cultural life was the Lanier Library, founded in 1889 by five women to foster the civic and educational welfare of the small community. They started with a few donated books and gradually raised money to buy more and a bookcase to hold them. Within six years, the white community put up a building named for the poet Sidney Lanier, who spent his last months in Tryon. By 1930 the Lanier Library had turned into a community center where white patrons came not only to read books but to attend lectures and classical music recitals.

Though the railroad tracks ran through the center of Tryon, blacks and whites did not live exclusively on either side. Rather the two races lived near each other in checkerboard clusters, an arrangement that fostered, depending on one’s viewpoint, an inchoate integration or an imperfect segregation. Families exchanged pleasantries and the bounty from one another’s gardens; the men worked alongside one another on construction jobs. But these lives mixed only up to a point. Black laborers, including the teenage John Irvin, helped build the bowling alley and movie theater, but the alley was whites-only, and when the theater first opened, blacks had to wait for special showings so late in the evening that the children fell asleep before the feature was over. Eventually blacks could go whenever they wanted, but they had to purchase their tickets from a separate window, buy their popcorn and soda from a separate makeshift stand, and sit in the balcony. The man in the booth would sell a ticket to a white customer at the front and then pivot to the left to sell one to his black customer. White families occasionally treated their black help to movie tickets, gently instructing them where to go as employer and employee went their separate ways before the movie started. Blacks appreciated such gestures, and took them as a sign of working for good folks who looked after them. Black and white children went to separate schools. If they played together as youngsters, that ended by the time they were teenagers. The color line could nonetheless be a rude awakening, perhaps because it existed in such a seemingly benign atmosphere. Nine-year-old Carrol couldn't understand at first why he wasn't allowed to take out a book from the library. He turned the rebuff into a poem.

They said the library was for everybody,

I thought that meant me, too—I was a body—

It was the Tryon town Public Library—

I lived in Tryon town, too—I was a public.—

They said they wanted all the kids to come.

I thought that meant me, too—I was a kid—

'Cause I didn't know what they meant when

they told me what they said…

Though no one talked much about it, J.D. and Kate and their friends remembered the lesson Scotland Harris, a teacher, learned about the town’s racial norms. He had come to Tryon at the behest of the Episcopal diocese to open the Tryon Industrial Colored School. His first few years went smoothly, but when his classes grew more adventuresome, the city’s white elders spoke up. They chastised him for teaching his young black charges to aspire to lives and careers beyond Southern custom and tradition, and they told him to stop. “Of course he continued,” recalled his granddaughter, Beryl Hannon Dade.

The white elders also looked askance at the large house Harris built at the crest of a hill on Markham Road, which wound its way from the north end of Tryon through the east side of town. Harris’s students had helped with construction as part of a real-world exercise in their shop class, and the house was among the grandest in Tryon, even including the white areas.

The final straw for Harris came when he accepted a white friend’s invitation to attend the man’s church, Holy Cross Episcopal, on the fashionable Melrose Avenue. On the appointed Sunday, Reverend Harris and his entire family entered the sanctuary with other congregants and sat down in one of the Holy Cross pews. “Well, of course you don't do that,” Beryl Dade said. “It was a social barrier that was crossed.” A short time later the head of the diocese, a white bishop, asked Harris to leave Tryon. He leveled no threats, but Harris got the message. He chose not make a fuss and agreed to take another post. His departure highlighted the precariousness of black life in Tryon, its residents ever mindful that in more hostile communities such a moment could easily explode into violence.

The Tryon Daily Bulletin, the town paper, documented social life along with the news, recording the comings and goings of the celebrities who vacationed there as well as showing through its copious ads the latest at Ballenger’s department store, the specials at the A&P, and the host of items that could be found at the two drugstores nearly adjacent to each other on Trade Street, Owen’s and Missildine’s. Both served as gathering places for the town’s business folk, like-minded white men adopting one or the other as their haunt, though the Missildine’s lunch counter was considered the elite spot and Owen’s “the subsidiary.” “You only went to Owen’s if you got mad at somebody at Missildine’s,” recalled Holland Brady Jr., who watched some of these tête-à-têtes with the enthusiasm of a teenager learning the ways of the world.

The Bulletin devoted most of its stories to Tryon’s white community, though the paper included short articles about black Tryon under the heading “Colored News.” Black residents also used the Bulletin, listing notices for PTA meetings or special programs at the Tryon Colored School or announcements of events at their churches. Specific requests for assistance, each carefully worded, conveyed not only what was needed but gratitude that such a request could even be made and then granted. “Donations or will buy a used typewriter to be used at colored school,” said one. “We have a project outlined to make our school more progressive. We are asking our white friends to continue to support us as you have done in the past. We always appreciate the interest you manifest in us.” Famous gospel groups such as the Dixie Hummingbirds advertised their local performances, and on occasion they agreed to match voices with the area’s top groups. “White friends invited,” the ads concluded.

The Bulletin didn't have a regular classified section, but residents were free to write their own ads seeking help or offering their services. Racial preference was explicit in both categories: “WANTED: White girl to stay on place. Must be able to cook.” “WANTED: Colored Farm Hand to do general work. Unfurnished house. free milk; garden space of his own.” “Experienced colored butler (old school) wants job. Excellent references.”

J.D.’S DRY CLEANING STORE sat right on Trade Street snug up against the railroad tracks, not far from the depot and catty-corner from the A&P and the Sinclair station. His prized possession—and he was sure it was the first in Tryon—was a Hoffman finishing press fired by a boiler and controlled with a foot pedal. The other cleaners (as far as he knew) still had to contend with the cumbersome routine of a hand-held iron. Because J.D. sewed, he offered customers repairs and alterations. When the jobs were done, he delivered the clothing as promised, and almost always took John Irvin with him. Eager to get the most out of his space, J.D. also started a barber business, tucking his barber’s chair in a little room next to the dry cleaning apparatus. Word spread through town that “Mr. Waymon can do white hair”—even the popular “Washington Square,” a cut named for the squared-off look at the back just above the collar. J.D. got so busy that he hired a Mr. Broomfield to help him.

J.D.’s smooth transition into Tryon was shattered one day in the most unusual way. He and John Irvin arrived early, as was J.D.’s custom. Before making a fire in the boiler he always cleaned out the flue. Then he took old newspaper and rolled it into tight cylinders to use as kindling. On this morning when he lit a match to start the fire, nothing happened. He tried again with the same result. After the third time, he went outside and up on the roof to see what the problem might be. That’s when he noticed an inner tube full of gasoline that someone had stuffed at the top of the chimney. Had the rolled-up newspaper started to burn, the shop would have been destroyed and J.D. and John Irvin injured or even killed.

J.D. didn't know whether this was a prank or a more sinister act to put him out of business. Years later a couple of the children claimed it was the Ku Klux Klan that tried to intimidate their father. But John Irvin doubted it. “I didn't know nothin’ about the Klan” in Tryon, he said, and while the town itself had never been a hotbed of Klan activity, the organization did have a foothold in more rural—and racially tense—parts of Polk County. J.D. credited a “higher power” with preventing a tragedy.

Her husband’s spiritual explanation made sense to Kate; it matched her growing interest in religion, specifically activities at St. Luke CME, one of Tryon’s black churches. “She went Christian,” as John Irvin put it, and he felt the change. Music still filled the Waymon house, but now it was the sacred instead of the secular when Kate sang and accompanied herself on a little pump organ, just the way she had as a child in Inman.

The family’s life was actually disrupted not long after the incident at the shop, when their rented house caught fire in the middle of the night. John Irvin never forgot how his father tumbled out of bed, grabbed a shotgun with one hand and his pants with the other, and ran outside to shoot off the gun, a signal for help. One of the pant legs had turned inside out, and though John Irvin knew it was a serious moment, he couldn't help laughing at the sight of his father tipping back and forth to get to the door. “But he shot that shotgun,” John Irvin said. Help came, and no one was injured.

It was probably in 1931 or 1932, after the fire, that the family moved to a house on a curving, hilly road, later named East Livingston Street when Tryon authorities finally established more precise municipal boundaries. Though not large for a family of seven, the house had a number of advantages, best of all a yard big enough so the family could have a garden and keep some chickens. A fence in the back separated the house from a pasture where the neighbors kept their cow.

The large main room had one of the two stoves, and the children usually slept there. The other stove was in the kitchen. When bath time came in the evening, either J.D., Kate, or one of the older children heated a tub of water on top of the living-room stove, and the children took turns cleaning up. John Irvin got so close to the stove one chilly night that he burned himself, the scar a permanent reminder of the bathing ritual. Kate and her good friend Alama King, who lived down the road with her husband Miller and daughter Ruth, used the front steps and the little porch as their visiting spot. Ruth...