![]()

1

At River’s Edge

Abraham Galloway grew up in a world that gazed out to the open sea. He was born on 8 February 1837 in a little hamlet of ship pilots and fishermen called Smithville.1 The village perched at the mouth of the Cape Fear River, twenty-eight miles downriver of Wilmington, North Carolina. At the time of Galloway’s birth, Smithville had a population of roughly 800 inhabitants, nearly half of them slaves. Pilots had settled there by the inlet a century earlier so that they could watch for ships signaling for their services as they approached the river’s mouth from the Atlantic. Smithville grew up around the cottages of the ship pilots, though no one bothered to lay out the boundaries or incorporate the town until 1792. A small garrison of soldiers was also nearby at Fort Johnston, where the walls were constructed of what its slave builders called a “batter” of sand and oyster shells cooked together. The fort overlooked the river and had played a key part in Wilmington’s defenses during the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812.2

The Smithville of Galloway’s childhood consisted mostly of weathered clapboard cottages, fishing camps, and a few modest summer inns. The only public buildings were the fort, a plain wood-framed courthouse, a small seamen’s hospital, and a jail that, judging from a surviving inventory of its inmates, was a second home to a great many of the pilots. There were two churches, Grace Methodist and St. James Episcopal, and a graveyard shaded by live oak trees. Legend had it that one old oak marked the eastern end of an important trading path that ran between the coastal Siouan tribes and the Catawba Indians in the upcountry. Nearby, the last of the local Indian tribes had made their final stand in a battle on a high sand dune called Sugar Loaf in 1718. During Galloway’s childhood, river pilots still used Sugar Loaf as a navigational landmark between Smithville and Wilmington.

The village had a casual, seaside air: fishing nets dried in backyards, cows and horses wandered the streets, and gangs of men and boys could always be found lollygagging around the wharf waiting for the next Wilmington or Charleston packet. From a watchtower on the waterfront, pilots kept a lookout for incoming vessels, while slaves plied the river in boats loaded with fish and oysters. Sometimes the slave boatmen sang sea chanteys that they had learned from sailors, such as the one about a beautiful Jamaican mulatto that a Smithville visitor heard slave boatmen croon a few years before Galloway’s birth. The visitor wrote the chantey’s first lines in his diary: “Oh Sally was a fine girl, oh! Sally was a fine girl, oh!”3

At dusk Smithville’s residents watched the faint silhouettes of slaves paddling dugout canoes on the river. Many slipped out of rice field canals upriver by night to get off their plantations.4 Under cover of darkness, they fished and hunted, attended worship services, or visited loved ones. A number cut firewood after finishing their field work and secretly sold it to steamboats moored in the river. Such forays were likely the young Abraham Galloway’s first acquaintance with the world of stealth and darkness.

In Galloway’s youth, wealthy planters and merchants and their families came to Smithville to get away from the low country, with its swamps and flooded rice fields, during the malaria season. They enjoyed long walks by the waterfront and played about in boats. In the surrounding countryside, the toll of plantation bells marked the rhythm of daily life, but in the village itself, slave life revolved around wind and tide and the comings and goings of ships. Those ships may have inspired in the young Galloway, as they did in Frederick Douglass, visions of liberty and freedom. In his classic account of his boyhood as a slave on Maryland’s Eastern Shore and in the port of Baltimore published in 1845, Douglass recalled the “beautiful vessels, robed in purest white” that might “yet bear me into freedom.”5

Galloway’s mother and father also lived by the sea. His mother, Hester Hankins, and his father, John Wesley Galloway, both resided in Smithville.6 She was a slave; he was a free white man. Born in 1820, Hester Hankins had skin the color of ebony, never learned to read or write, and in legal terms, belonged to a local woman named Louisa Hankins, the widow of a Methodist clergyman who died in a boat capsizing off Oak Island in 1835. Hester Hankins probably worked as a house servant and occasional field hand.7 How she met Abraham’s father remains unclear. All that is known is that she bore her first child when she was seventeen years old. Hester Hankins named her child “Abraham”—his full name was Abraham Harris Galloway—after the great Old Testament nomad who led his followers from Ur to Canaan.8 She and her son Abraham remained close throughout his life.

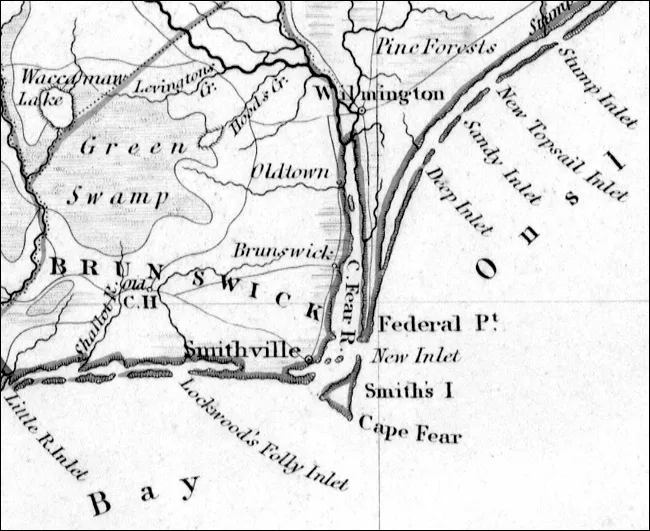

Wilmington, Smithville, and vicinity around the time of Galloway’s birth. Detail from Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, North America, sheet 11, Parts of North and South Carolina (London: Chapman & Hall, 1844). Originally published in 1833. Courtesy, New Hanover County Public Library, Wilmington, N.C.

The life of Abraham’s father is better-documented. John Wesley Galloway’s extended family included some of the leading planters in Brunswick County, of which Smithville was the county seat. John Wesley, though, was not a planter but a boatman, a ship’s pilot on the Cape Fear River and, sometime after 1850, captain of the Federal lightship moored off Frying Pan Shoals.9 A dashing, free-spirited young man with penchants for both classical learning and the camaraderie of sailors and fishermen, he was descended from seafarers who had left Scotland to settle in America in the eighteenth century. His ancestors included ship’s pilots in Charleston Harbor and a grandfather who led Stamp Act protests against the British and joined the Sons of Liberty during the Revolutionary War. His father left the sea trades, invested in slaves, and built a plantation on the salt marshes of Lockwood Folly River, south of Smithville.

Forsaking his father’s life as a planter, John Wesley made his home among the lowly pilots’ cottages in Smithville.10 A tall, lean, broad-shouldered man, he was said to be “strong, manly, attractive.” Another of his sons later recalled that their father was “very muscular, active as a kitten, and possessing the kind of courage out of which heroes are made.” He added that “in common parlance he would not do to fool with.”11 According to family stories passed down through the generations, John Wesley Galloway also possessed an exaggerated sense of honor and a stubbornness that bordered on arrogance.12 He shared many of the aristocratic values of his wealthier cousins, but he never owned much more property than a small lot in Smithville and the six African Americans that he inherited after his father’s death in 1826.13 In a little more than a decade, John Wesley lost or gave up all but one of those slaves. His last remaining slave, Amos Galloway, became Hester Hankins’s husband in 1846.

The circumstances of the relationship between John Wesley Galloway and Hester Hankins remain murky. At the time that Abraham was conceived, the summer of 1836, John Wesley was a twenty-five-year-old boatman in the employ of the U.S. Coast Survey, which was constructing a fort on the south side of the main inlet into the Cape Fear River. Though state law and social custom strictly prohibited sexual relationships between slaves and free persons, they were commonplace in Brunswick County, as elsewhere in the South. In the case of John Wesley and Hester, a family bond may have brought them into the same orbit. John Wesley was a second cousin to Hester’s owner.

The most striking characteristic of the relationship between Hester Hankins and John Wesley Galloway is that, according to the adult Abraham, John Wesley “recognized me as his son and protected me as far as he was allowed to do so.”14 White men frequently fathered children by slave women in the plantation South, sometimes as part of affairs of the heart but more typically as a product of coercion or rape. For a white man to publicly acknowledge a slave child, however, was a rarity in the antebellum South. John Wesley’s recognition of his paternity of Abraham held special significance because it was also a public avowal of his relationship with Hester Hankins. In 1837, when Abraham was born, neither the law, church doctrine, nor local custom encouraged John Wesley to acknowledge or accept any responsibility for an African American son. Quite the opposite was true. John Wesley’s public claim of his fatherhood and his efforts to protect his slave son must have been significant to Abraham, perhaps even more so for their rarity.

Abraham’s words—his father “protected me as far as he was allowed to do so”—also suggest that he had a rebellious and probably perilous childhood. He obviously needed his father’s protection at least occasionally or he would not have been aware of John Wesley’s willingness to save him from harm or, for that matter, discovered the limits of his ability to do so. How much protection John Wesley could give Abraham is questionable. If he had been one of the Cape Fear’s great planters, the sort of man who oversaw a small fiefdom and on whom an entire neighborhood relied for credit and the use of his rice mill or turpentine distillery, his sway would have been far more considerable. If he chose to do so, such a planter might cast a blanket of protection over a slave child in another man’s possession. That was not John Wesley’s situation. He was of good family and well respected along the waterfront but scarcely a figure that inspired fear or awe by virtue of his wealth and power. When he shielded Abraham from the whip or the auction block, he did so either by drawing on bonds of family and friendship or by the fierceness of his temper and his capacity to inspire fear in those who crossed him.

Two years after Abraham’s birth, in 1839, John Wesley Galloway married the daughter of one of the other ship pilots in Smithville. The couple had eight children together before the Civil War. How much contact the young Abraham had with his younger white half-brothers and half-sisters during his childhood is not known. However, in a legal deposition taken more than half a century after the Civil War, Abraham’s widow indicated that her husband had often spoken familiarly of John Wesley’s oldest son from his marriage, Alexander Swift Galloway. Swift Galloway, as he was known, was only three years younger than Abraham and seems to have been one of Abraham’s playmates when they were children in Smithville.15

As the two half-brothers grew older, their fates took very different turns. Along the Cape Fear River a slave child’s life was always, to borrow Tennyson’s famous phrase, “red in tooth and claw.” The fragility of slave families and the hardness of slave children’s lives are the dominant themes in court documents, bills of sale, and wills and estate records, but most especially in the accounts of antebellum life written by former slaves.16 Those firsthand accounts of growing up in slavery on the Lower Cape Fear offer a litany of bloody scenes. Typically, the memoir of the Reverend William H. Robinson, who was born in Wilmington in 1848, recalled how, as a child, he commonly witnessed slave women beaten, abused, and sexually humiliated in public. He saw children whipped. He was only twelve years old when he witnessed a young friend—a fugitive slave—shot to death by bounty hunters. Over the years, the boy lost his father, his mother, and all of his brothers and sisters to the auction block. He himself was beaten severely at least once, probably at the age of nine or ten, when he tried to put himself between his mother and a brutal assailant.17

The most powerful scene in his memoir, From Log Cabin to the Pulpit; or, Fifteen Years in Slavery, is a vivid account of his sale at the slave market in downtown Wilmington. He was twelve years old at the time. Saying little about his own anguish, Robinson focused instead on the plight of a young mother and her children whom he met in a slave pen where they were kept in the weeks leading up to the auction. The sale itself was traumatic, but what came next was worse. During a long march, in shackles, from Wilmington to a slave market in Richmond, the young Robinson watched the slave trader viciously whip the young mother in front of her children when they could not keep up with the other slaves. In the end, the slave trader sold her toddler and infant away from her so that they would not slow him down. The depth of her sorrow at that moment haunted Robinson for the rest of his life.18

That was young Abraham Galloway’s world. Unlike Robinson, he never disclosed details of his childhood. But whether his early years closely resembled those of Robinson, were comparatively carefree, or were even worse, his life as a slave ultimately had to separate him from his white half-brother. While Abraham never attended school and never learned to read or write as a child, Swift studied with a master scholar, Walter Gilman Curtis, a tutor on a local plantation and a former Harvard professor. Looking away from the sea for his livelihood, Swift finished his studies and taught school in Smithville just prior to the Civil War. After the fall of Fort Sumter, he enlisted in the Confederate army as a second lieutenant in the 3rd North Carolina Infantry. He was wounded seriously at the Battle of Malvern Hill, but he recovered, joined another infantry unit, and was promoted eventually to captain. Near the war’s end, Swift served as superintendent of the Confederate prison camp in Salisbury, North Carolina.19 All of that time, his older half-brother and childhood playmate was doing everything in his power to bring about the Confederacy’s downfall.

Galloway was never his father’s property. Instead, a youth named Marsden Milton Hankins held the deed to him, Galloway later said, “from infancy.”20 Hankins was a Smithville lad only seven years his senior.21 The boy was the son of the Methodist minister who perished in the 1835 boat capsizing off Oak Island—he was one of the few survivors—and he and his mother, Louisa Hankins, remained in Smithville at least until Abraham’s birth in 1837.22 The widow Hankins eventually remarried, giving her hand to Miles Potter, an older planter who owned twenty-two slaves and 400 acres at Town Creek in 1850.23 In time, Milton apprenticed under a master mechanic and moved upriver to Wilmington to work as a railroad mechanic and engineer. At roughly the same time, probably when he was ten or eleven years old, Galloway apprenticed as a brick mason in either Wilmington or Charleston, the two closest cities where the demand for skilled building trades was sufficient to req...