![]()

1

Migrants’ Routes, Ties, and Role in Empire, 1850s–1920s

If you were leaving your home on an eastern Caribbean island in the 1870s or 1880s, you were probably heading south. Perhaps you boarded an intercolonial steamer in Bridgetown, your passage buying you the right to jostle for space on the open forward deck, amid scores of men and women from Martinique off to seek work at the gold mines of Venezuela. If a storm came up, as it often did, daybreak would find all of you unpacking boxes and bundles, hanging carefully stitched skirts and elegant hats out to dry before landfall in St. Vincent. Or perhaps you boarded the Royal Mail packet in St. George’s, Grenada, looking up once more at the town layered in the curve of the volcanic crater, “rows of red-tiled roofs gleaming in the sun one above the other, nodding palms and flowering trees between them.” By afternoon you would reach the Gulf of Paria. The dark sierras of Venezuela spread to the right, the green mountains of Trinidad to the left. The rocky cliffs of the Dragos islets loom above on either side as your ship passes through to the gulf.1

Then days or a week in Port of Spain, waiting for a returning cattle boat on which to purchase passage across the Gulf of Paria and up the muddy brown current of the mighty Orinoco River. Paddle-wheel riverboats claim the main channel; dugout canoes hug the mangrove-lined banks. Patois and English and Spanish sound around you on deck. In three days, Ciudad Bolivar appears, two-story commercial houses lining the riverfront, customs agents and porters (some from your very island) bustling to and fro. You might find room in a lodging house run by “a good old Barbadoes woman,” as one Englishman did in 1869. He was surprised by the conversations he heard, though you would not have been. Mother Saidy’s “was a sort of reunion for all the niggers from the British West India Islands,” he wrote, “where they met to discuss affairs private and political. It was most amusing to see what pride they took in being British subjects, and the contempt in which they held their dark brothers of the Main” (that is, Venezuela).2 To this Englishman, the political opinions of black Caribbeans abroad seemed “amusing,” no more. But sojourners’ allegiance mattered in this era, and not only to sojourners themselves.

This chapter introduces the places that came to form part of the circum-Caribbean migratory sphere and the people who made it so. Histories of receiving-society enterprises that employed British Caribbeans in this era routinely refer to “imported Jamaican workers.” But to think of Caribbean sojourners as commodities imported by employers is inaccurate. The number of British Caribbeans traveling to any given destination under contract was always smaller than the number who made the trip at their own expense and under their own authority. Certainly, they went where employers wanted them. Labor-market disparities drove emigration: scarce options here, higher wages there. But migrants’ economic decision-making reflected an evolving social panorama shaped by those who went before. Transnational networks of kith and kin determined which opportunities would-be migrants heard about, what resources they could mobilize to get there, and who they could fall back on if plans went awry. Migration remade the human geography of the nineteenth-century Greater Caribbean because migrants made it so.

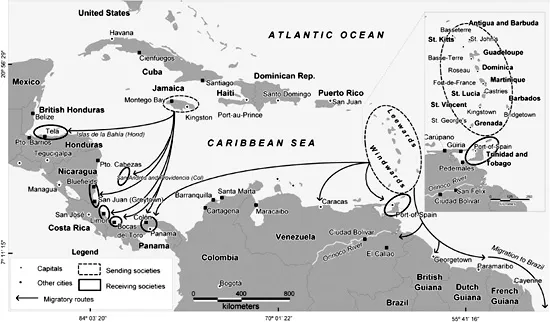

The mobile world that reached its zenith in the early 1920s had its origins three generations before, at the end of slavery. As Caribbean freedpeople and their children sought opportunity and autonomy, two fundamental strategies emerged to lessen dependence on the plantations where they or their parents had labored as slaves: people headed either into the hills or out to sea. Efforts in the first direction created what later scholars tagged “reconstituted peasantries,” as hundreds of thousands of Afro-Caribbeans turned to growing provisions and export crops (cocoa, bananas) on land they purchased, inherited, or held in common with extended family. The seaborne strategy began with small-scale and seasonal movement between adjacent islands or nearby territories. Separate migratory circuits developed in the eastern and western Caribbean, linking Barbados, Trinidad, Guiana, Venezuela, and the Windward Islands in the east and Jamaica and the rimlands of Central America and Colombia in the west.

As U.S. investment in infrastructure and export agriculture surged at the end of the century, movement intensified. Work on the Panama Canal under U.S. government control brought eastern and western circuits together for the first time: scores of thousands of Barbadians joined thousands of “small islanders” and over 100,000 Jamaicans who traveled to or through the isthmian port of Colón. Cuba’s interwar sugar boom created another wave of opportunity, drawing 150,000 or more British West Indians, mostly from the western Caribbean. The sugar plantations of the Dominican Republic drew eastern Caribbean migrants in a parallel process. Meanwhile, the expanding economies of the southeastern Caribbean set hundreds of thousands of migrants in motion—some from far away, like the many scores of thousands of South Asians who reached Trinidad and Guiana from British India under contracts of indenture; others from nearby, like the scores of thousands of Windward Islanders who traveled to and through Trinidad and Venezuela in the same years.

Relying on word of mouth, mails, money orders, and cheap deck passage, migrants kept in touch. In addition to kin ties, British Caribbeans created a rich associational life, founding churches, lodges, and mutual aid societies with branches across the region. Did they find the prosperity they sought? Migrants encountered or created a huge range of work relations. The degree of coercion they faced varied enormously, determined less by which nation they were in than by where they were within it. Port cities, squatter hinterlands, plantation zones, and jungle camps each offered a characteristic mix of opportunities and pressures. In order to understand why, we must look at the intersection of local politics and geopolitics, asking what laws and what logic governed sending- and receiving-state attitudes to the Afro-Caribbeans crossing their borders. Subsequent chapters will argue that interwar political shifts ruptured the circum-Caribbean migratory sphere, with intensely generative consequences. This chapter lays out what the “before” had come to look like, so that you will understand just how different the “after” was.

THE MAKING OF A MOBILE WORLD: CIRCUM-CARIBBEAN MIGRATION FROM THE MID-NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE EARLY 1920S

The complexities of nineteenth-century migrations are well illustrated by the range of routes into and out of Venezuela, the Spanish-speaking nation that received more British West Indian immigrants than any other until construction of the Panama Canal under U.S. sponsorship began in 1904. In the Windward Islands and adjacent continental rimlands, the eighteenth century had seen borders move across people even more often than people had moved across borders. Imperial possession of these territories shifted back and forth, as France, Spain, Holland, and Great Britain vied for position on both the European continent and the Caribbean Sea. Only Barbados, with its flourishing sugar plantations well garrisoned, remained British throughout. Struggles against slavery—and the empires’ halting efforts to abolish or reimpose it—sent fugitive slaves or fearful slave owners across imperial borders as well. By the 1820s, Guadeloupe and Martinique were consolidated as French possessions; the other Windwards (Dominica, St. Lucia, St. Vincent, and Grenada), Trinidad, and Guiana (including Demerara, Berbice, and Essequibo) as British colonies; and the continental territory west of Guiana as the now-independent Republic of Venezuela. Yet commercial circuits and family networks continued to cut across these nominal boundaries, and French patois-speaking Caribbeans of African ancestry moved with ease between Venezuela’s northeast coast and the nearby islands. The coastal ports of Cumaná, Carúpano, and Güiria were all far easier to reach from Port of Spain than from Caracas, as was Ciudad Bolivar, the Orinoco River port through which all exports from Venezuela’s western Andes, central plains, and southern jungles traveled to the Atlantic.3

Gold was discovered in the sparsely settled lands south of the Orinoco delta in 1849, the very year of the better-known California strike. Almost all of the eager prospectors and would-be entrepreneurs drawn to the strike’s site, El Callao, were British West Indians. Some traveled overland from Guiana, others by sail from Grenada, St. Vincent, and the other Windward Islands to Port of Spain and then southward by steamer or sloop. By the 1890s, it was estimated that more than 7,000 Dominicans resided in Venezuela, while many more had gone and returned—this out of a total island population that remained under 27,000 in 1891.4 As gold mining and rubber tapping boomed and contracted in turn, the British Caribbean population in El Callao and points south and west topped 5,000, creating constant demand for provisions and supplies. British West Indian settlers around Ciudad Bolivar, similarly estimated at over 5,000 souls at the end of the nineteenth century, grew foodstuffs, raised mules, and profitably provisioned the camps to the south.5

In the same years, cocoa farming for export boomed on the Paria Peninsula to the north, pulling entrepreneurs and traders from locations as far afield as Corsica, Lebanon, and Spain. Carúpano, center of the cocoa trade, flourished. The first cable line between Europe and South America was anchored here in 1877 so that local buyers could adjust prices in line with the latest European market news. Those Paria residents who had arrived years before from nearby islands had often managed by the late nineteenth century to acquire smallholdings of their own and gain some prosperity as independent cultivators. Later arrivals more often found work as laborers on plantations owned by Corsican or Venezuelan merchants. Most of these British islanders, whether newly arrived or long resident, prosperous or poor, were Afro-descendant, patois-speaking men. In the same years, some 1,000 island-born women and men from Guadeloupe, Martinique, and the British Windwards labored as servants and artisans in Venezuela’s capital, Caracas.6

Similar patterns of movement shaped the western fringes of Britain’s Caribbean claims. Travel between Jamaica and Central America’s Caribbean coast, long linked by the circulation of traders, turtlemen, and fugitives, accelerated after the end of slavery in the 1830s. The building of a railway across Panama by U.S. investors in 1850 relied upon Jamaican laborers, as did the Ferrocarril de Costa Rica, built from Port Limón up to Costa Rica’s coffee-growing Central Valley in the 1870s. Abortive French efforts to build a canal across Panama in the 1880s drew scores of thousands from Jamaica to work on the diggings and scores of thousands more to seek opportunity in the boomtown service economy canal workers’ demand drove.7 Linked by bonds of empire and language to those running the show, Martinique and Guadeloupe, too, sent significant numbers to Panama in this era.

British Caribbean Migration, 1870s–1900s

But it was not until canal construction resumed, under the aegis of the U.S. government, after 1903 that eastern Caribbean islands were linked to western Caribbean destinations in a significant way. The U.S. Canal Commission established its recruiting headquarters in Bridgetown in 1905. Some 20,000 Barbadian men left under contract for Panama over the next decade. Another 25,000 Bajans headed to the isthmus on their own dime in the same era, seeking their fortune outside the formal construction economy; perhaps half of these latter were women. Overall, nearly one-fourth of Barbados’s working-age men worked in Panama in this era.8

Even during the exodus to Panama, the long-standing pattern of Barbadian emigration southward to Trinidad continued apace. The durability of highly specific migratory circuits is striking and utterly typical of what migration scholars have found for other places and times. People traveled to places where people they knew had already gone. In the years that St. Vincent and Grenada had sent many thousands to Venezuela, similar numbers of Barbadians had left instead for Trinidad (and smaller numbers for British Guiana and Brazil)—perhaps some 20,000 in the 1860s alone. The turn of the century found 14,000 Barbadians resident in and around Port of Spain; the population of Barbados’s own capital, Bridgetown, was under 13,000 at the time.9 Booming commerce to and through Port of Spain carried steady numbers of interisland hucksters and job seekers along on boats like the fifty-four-ton Wild Rover, which arrived from Bridgetown in November 1...